[Two VERY different books for you today on the Galactoscope…]

by Victoria Silverwolf

Wonder Stories From Wisconsin

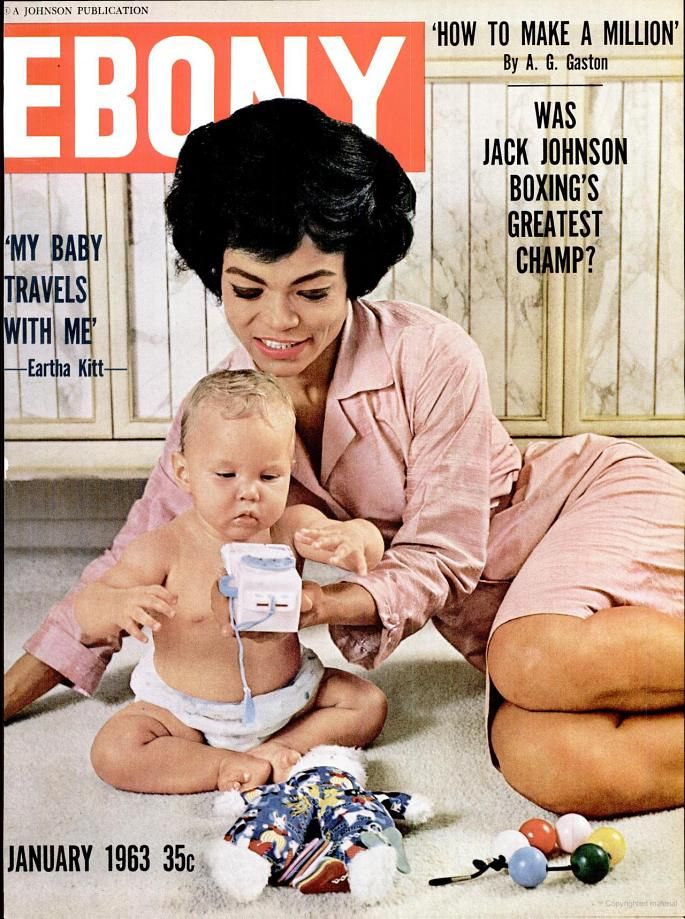

Science fiction readers hardly need an introduction to the works of Clifford D. Simak. Born in Wisconsin in 1904, and working for the Minneapolis Star newspaper since 1939, he published his first story, The World of the Red Sun, in Wonder Stories in 1931.

Getting your name on the cover with your first story is quite an achievement. Art by Frank R. Paul.

His best known work may be City (1952), a book consisting of eight linked stories. It won the International Fantasy Award that year.

Cover art for the first edition by Frank Kelly Freas. There have been many other editions since.

He also won the Hugo Award for Best Novel with Way Station (1963), serialized in two parts in Galaxy as Here Gather the Stars.

(The Noble Editor gave the serialized version a mediocre three star rating. I read the book version and loved it. Chacun son goût!)

Cover art by Ronald Fratell.

Simak has a reputation as a gentle, humane pastoralist. His stories often celebrate nature and the outdoors, particularly the wilds of Wisconsin, and show compassion for all living beings. His latest novel displays this side of his character, to be sure, but it also has a darker, pessimistic mood that may not be as familiar to his readers.

Here's the author with his Hugo, looking just as friendly and optimistic as you'd expect.

Cold War

Cover art by Robert Webster.

In the year 2148, society is dominated by the Forever Center, a private company whose headquarters are located in a mile-high skyscraper. Their function is to store the frozen bodies of the recently deceased, in order to revive them into young, healthy, nearly immortal bodies in the near future. The catch is that they haven't quite figured out how to do this yet.

(If this reminds you of a proposal made by R. C. W. Ettinger, and discussed in a few issues of Worlds of Tomorrow, go to the head of the class. Simak explicitly mentions Ettinger in the novel.)

R. C. W. Ettinger. He also published a couple of science fiction stories some years ago.

In the real world, freezing people in the hope of reviving them has already begun. James Hiram Bedford, a professor of psychology, died on January 12 this year. His body was immediately chilled far below zero and placed in storage.

Bedford's body is injected with dimethyl sulfoxide, as part of the preservation process.

Nobody yet has the slightest clue about how to bring people like Bedford back to life. Besides that little technical problem, there's also the dilemma of where to put all these people when they're thawed out, if this process ever gets under way big time. Simak addresses that very issue.

The novel says there are about one hundred and fifty billion frozen corpses by the middle of the 22nd century, and a world population of one hundred billion! That seems very hard to believe, but it's a minor quibble. Simak tell us that food is provided through some kind of matter transformation rather than farming, so maybe that explains, to some extent, the gigantic population.

Humanity has achieved interstellar travel, but has not yet found livable planets for the huge number of expected revived folks. One possibility is terraforming these hostile worlds, but obviously that's going to be very difficult.

Another strategy, even more implausible, is to invent time travel, and send these people back millions of years into the remote past. The brilliant mathematician who is working on this problem vanishes, providing an important subplot.

The third suggested method, and the only one that seems remotely possible to me, is to cover the Earth with gigantic buildings, each one the size of a city.

Do you get the feeling that the Forever Center didn't really think things out too well? I believe that's part of Simak's satiric point, that the practicalities of freezing and resurrecting the dead have escaped those who are promoting it.

Despite these difficulties, the Forever Center virtually rules the world. People avoid risks and minimize spending, in order to have some wealth in their new life. Most people have transmitters near their hearts, so that when they die, rescue teams rush to carry their bodies into cold storage. Some people even choose to die, rather than wait for the Grim Reaper, in order to save money and make sure they're frozen safely.

The only folks who object to the Forever Center are the so-called Holies, who believe that humanity is giving up the hope of spiritual immortality for the promise of physical resurrection. The Holies are the ones who provide the book's title, writing that phrase on walls as a protest slogan.

A Man Alone

The protagonist is Daniel Frost. (An appropriate name!) He works in the public relations department of the Forever Center. A shady part of his job, which is not even known by his boss, is to exert a subtle form of censorship on the media. Anything that might make the company look bad is suppressed.

By sheer accident, Frost obtains a document that exposes corruption within the Forever Center. He doesn't even know what the document means, but it makes him the target of the company's head of security. Frost is knocked out and dragged into a kangaroo court, where he is convicted of treason to humanity, and given the second most dreaded punishment in the world.

(The worst punishment is to have your right to freezing and resurrection taken away. This happens to one of the novel's secondary characters, just because a mechanical breakdown of his vehicle prevented him from taking a dead person to the storage facility in time. His lawyer, who unsuccessfully tried to defend him against the judgement of a computer jury, becomes the protagonist's ally. She also serves as the love interest. Fortunately, Simak handles the romantic subplot in a more mature fashion than some writers.)

Frost is ostracized. Three circles are tattooed on his face, to warn people that they are not to have any relationship with him at all. (This is what gives the book its rather abstract cover image.) He is doomed to scavenge what food he can from garbage cans, and find shelter in ruined buildings.

(This part of the novel reminds me of Robert Silverberg's excellent story To See the Invisible Man, from the first issue of Worlds of Tomorrow.)

This portion of the book reads like one of Keith Laumer's more serious action/adventure/chase novels. Frost eventually winds up at a farm, now abandoned, where he vacationed as a boy. In what struck me as a wild coincidence, the missing mathematician — remember her? — happens to be there as well. She reveals a discovery that changes everything.

Although there's a happy ending for the main characters, with the good guys winning and love blooming, the book ends on a somber note. A fervently religious hermit provides the novel's last lines, and they aren't very hopeful.

The main plot is interrupted by chapters dealing with minor, often unnamed characters. These provide the reader with more details about this future world, and how the people in it react to the promise of physical immortality. There's a priest who has a crisis of faith, because he's chosen to be frozen and revived. There's an author who's written a carefully researched book exposing the Forever Center, but who can't get it published.

In addition to a traditional suspense plot, Simak provides philosophical musings about death and immortality. Although he's clearly on the side of the Holies, he avoids making things black and white.

I could quibble that parts of the story are implausible. (In a world with such a huge population, there are still tracts of unspoiled wilderness.) Some science fiction themes seem out of place. (The mathematician gets her inspiration from ancient alien records.) Overall, however, it's a thoughtful and serious book, well worth reading and pondering.

Why Call them Back from Heaven gets four stars.

by Cora Buhlert

A Ponderous Professor Among the Barbarians: Tarnsman of Gor by John Norman

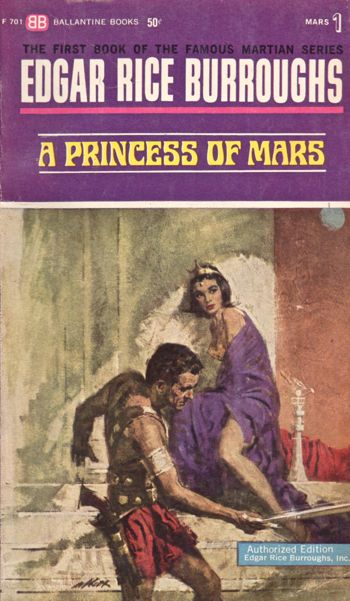

During my last visit to my trusty local import bookstore, the trusty paperback spinner rack yielded a book that looked promising. I had never heard of John Norman nor did I have any idea what a Tarnsman is or where Gor is, but the blurb on the back promised an Edgar Rice Burroughs style adventure on an unknown planet.

I took the book home and eagerly cracked it open, only to find myself faced with a lengthy and very dull opening in which our narrator, one Tarl Cabot, holds forth about the origins of his name (from the Italian, though his family hails from Bristol), his family history (father vanished, mother dead), his education (Oxford, naturally) and his position as a professor of English history. The diction and plodding pacing are more reminiscent of justly forgotten Victorian novels than of a thrilling adventure tale.

Frustrated by the demanding duties of a college professor such as grading term papers, Cabot goes camping and finds a glowing envelope with his name on it on the ground. Inside, Cabot finds a signet ring as well as a letter from his missing father. Shortly, thereafter a spaceship arrives and whisks Cabot away to the planet Gor, which shares the orbit of Earth but sits on the opposite side of the sun, rendering it indetectable. The similarities to Mondas from the Doctor Who serial "The Tenth Planet" are notable, but likely a case of both stories drawing on the same discredited cosmology.

Cabot learns all this from his estranged father, who seems genuinely touched to see his son, only to immediately begin lecturing him on the history and society of Gor, on the importance of Home Stones and on the all-powerful Priest-Kings who may be aliens or gods. Of course, neither Cabot nor we have seen anything of Gor yet, so we have no reason to care about Home Stones or Priest-Kings. The dialogue is stiff and unnatural and the lecture portions read like a particularly dull college textbook. John Norman is apparently the pen name of a professor of philosophy, which explains a lot.

Tarl Cabot spends the next few chapters learning about "the history and legends of Gor, its geography and economics, its social structures and customs, such as the caste system and clan groups, the right of placing the Home Stone, the Places of Sanctuary, when quarter is and is not permitted in war" and sadly, so must the reader. The one bit of all this lore that will be relevant later is that Gor has a rigid caste system and practices slavery. As a man of the Sixties, Cabot is horrified by both.

Slaves, Chains and Adventures

The story picks up when Cabot is initiated into the warrior caste and given a tarn – a giant bird of prey – to ride. Cabot is also given a mission, to steal the Home Stone of the rival city Ar. Unfortunately, this raid will also cost the lives of two women, the slave girl Sana and Talena, daughter of the warlord of Ar. Cabot is not happy with this either.

He frees Sana and returns her home, manfully resisting her offer of some very physical gratitude. Then Cabot flies off to steal the Home Stone of Ar. He manages to acquire the stone as well as an unwanted hostage in Talena, who clings to the saddle of his tarn in an attempt to save the stone. Talena succeeds and manages to hurl Cabot from the saddle. He is saved by an intelligent, talking giant spider in one of the few surprising twists of this tale.

Talena's triumph does not last long. The tarn dumps her and takes off, carrying the Home Stone of Ar with it, leaving Cabot to deal with Talena, who alternately needs to be rescued and tries to kill Cabot.

The story now settles into the pattern of capture, deathly peril and escape familiar to readers of Edgar Rice Burroughs' Barsoom books and similar fare. With the Home Stone gone, the people of Ar turn on the warlord and want to execute his entire family, including Talena. So Cabot and Talena are stuck with each other now.

To avoid recognition, Cabot pretends to be a wandering warrior and passes off Talena as a new slave he has captured. They join a merchant caravan and prickly Talena becomes more submissive, as she falls for Cabot, who returns the feeling.

Compared to the barbarians of Gor, Cabot views himself as an enlightened man of the twentieth century. That said, his relationship with Talena and the focus on hoods, shackles, collars, leashes, whips and stripping her off her garments is unpleasantly reminiscent of the less savoury entertainment found in certain bars in Hamburg's famous redlight district St. Pauli. The phallic implications of the Goreans' favourite execution method impalement cannot be ignored either. Robert E. Howard's Conan, who actually is a barbarian, treats his female companions with far more respect than Tarl Cabot.

The novel ends, as such stories must, with Tarl Cabot uniting the warring cities of Gor. He rescues Talena from execution, marries her and finally does what has only been alluded to so far. Then… Cabot wakes up in New Hampshire again, even though there is no reason for this except that the same happened to John Carter.

Just Read Burroughs

The parallels to Edgar Rice Burroughs' A Princess of Mars are obvious. But even though A Princess of Mars is already more than fifty years old, it offers more adventure and entertainment than Tarnsman of Gor.

Once the story gets going, it's fun enough, though not up to the standards Burroughs, let alone Robert E. Howard or Leigh Brackett. But the entire first third of the book is devoted to endless lectures. Even in the later portions, Norman interrupts a scene where Cabot is about to be executed in some awful way by having him discuss philosophy at great length with the villain who just sentenced him to death. Maybe Cabot tries to escape by boring his executioners to death, but given how otherwise earnest this novel is, I seriously doubt it.

Rating this book is difficult. On the one hand, it is less ridiculous than Lin Carter's The Star Magicians. On the other hand, The Star Magicians was also highly entertaining, while large stretches of Tarnsman of Gor are just dull.

One and a half stars

![[March 16, 1967] A Matter of Life and Death (<i>Why Call Them Back From Heaven?</i> by Clifford D. Simak; <i>Tarnsman of Gor</i>, by John Norman)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/670316covers-672x372.jpg)

![[October 16, 1966] Only the Lonely (November 1966 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/fantastic_196611-3.jpg)

![[December 13, 1963] SLOW-DOWN (the January 1964 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/631213cover-456x372.jpg)

![[November 13, 1963] Good Cop (the December 1963 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/631113cover-669x372.jpg)

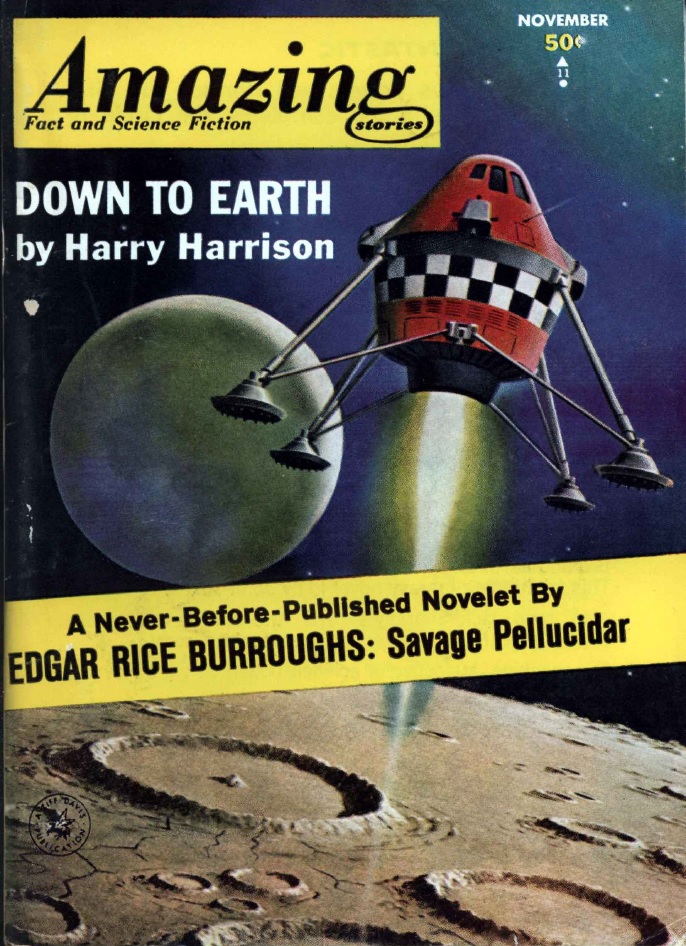

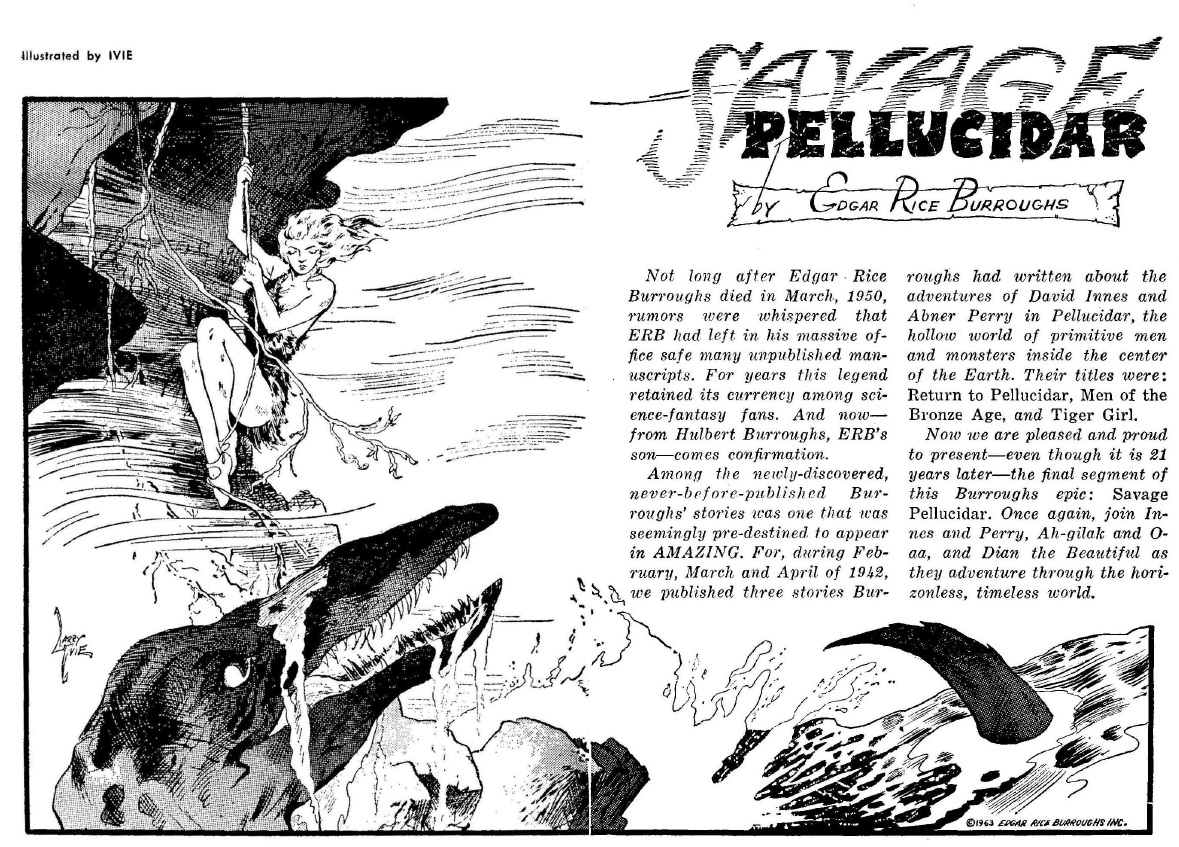

![[October 12, 1963] WHIPLASH (the November 1963 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/631012cover-672x372.jpg)

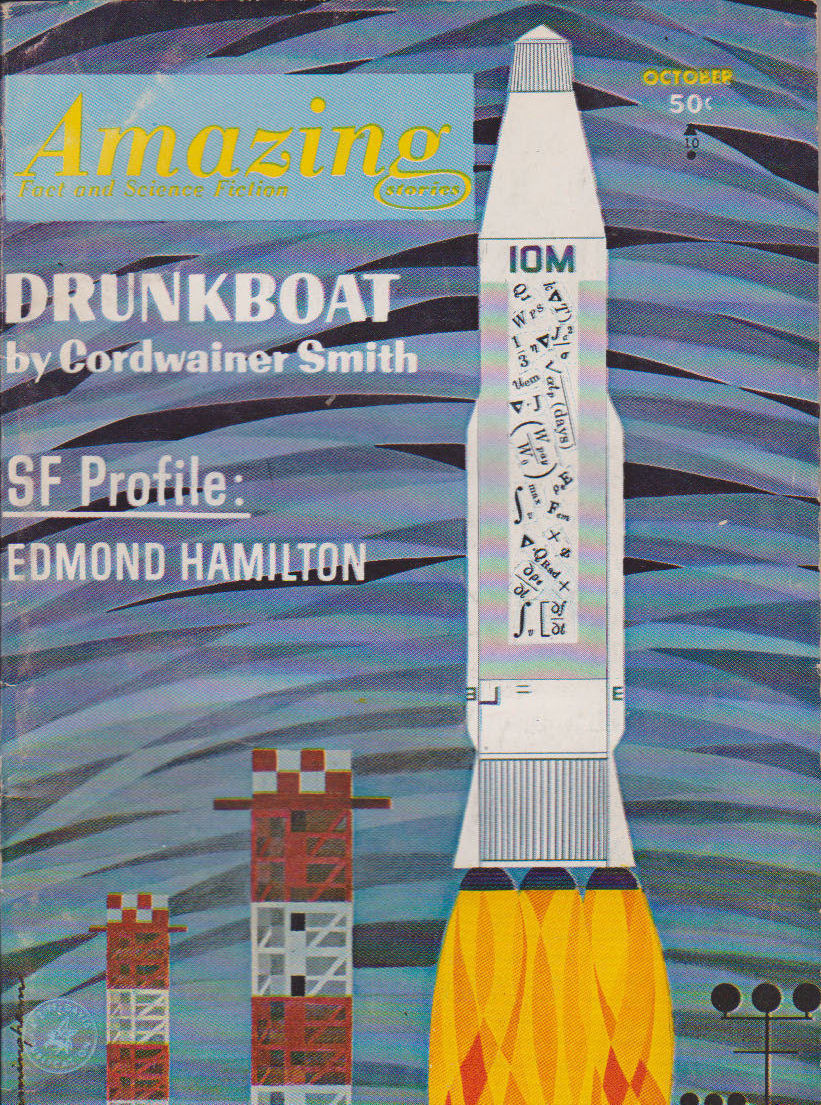

![[September 13, 1963] COMING UP FOR AIR (the October 1963 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/630913cover-672x372.jpg)