by Victoria Silverwolf

Philosophers have long debated the nature of reality. Are things what they seem to be, or do our senses deceive us? Do you and I perceive the world in the same way, and is there any way to know? Although there will never be a final answer to such questions, speculation about these matters can lead to intriguing works of fiction. The latest issue of Worlds of Tomorrow features many stories dealing with different perceptions of the universe: biased, distorted, ambiguous.

The Trouble with Truth, by Julian F. Grow

In the middle of the next century, Earth is united under a government run by computer. News is restricted to the listing of confirmed data, with no human-interest stories allowed. The narrator works for the world news agency. His job is to prevent advertisers from planting misleading articles, and to ensure that only verifiable facts are presented in the media. This leads to conflict with his fiancée, who runs a small monthly publication (barely tolerated by the authorities) which is not so restricted in its contents. One of the odd things about this society is that marriage is not the same as matrimony. The two main characters have gone through the first, but not the latter. Another notable fact is that the woman is pregnant, and the couple will be able to choose the sex of their unborn child. When a little girl and her father report a strange happening to the news agency, it leads to a change in the way the ruling computer views reality.

This story reminds me of Ray Bradbury in the way it promotes the importance of imagination over cold, hard facts. The world it creates is an interesting one, but many of the futuristic details are irrelevant to the plot. There's also a lot of expository dialogue. How you feel about the ending, which makes use of a very famous essay from the past, depends on your tolerance for sentimentality. It exceeded mine. Two stars.

The Creature Inside, by Jack Sharkey

This is the newest entry in the author's Contact series, previously published in Galaxy, in which the protagonist's consciousness enters the bodies of aliens. In this adventure, he has a very different assignment. A man is placed in a room that allows him to experience his fantasies as if they were real. The room also has a device that can manufacture whatever he wants from any raw material. The intent is to treat the man's inferiority complex. Unfortunately, he actually suffers from delusions of grandeur. The problem is to get him out of his imaginary world, where he would be able to survive indefinitely. The hero enters the room, where he encounters various illusions, as well as dangers that are all too real.

Although nothing very surprising happens, the hallucinations are vividly described and the story holds the reader's interest. The protagonist learns something about his own desires, adding a nice touch of characterization to an otherwise unmemorable hero. Three stars.

The God-Plllnk, by Jerome Bixby

Two alien beings witness a strange object land on Phobos. They assume it is a god, because it resembles a gigantic version of themselves. They presume that the creatures emerging from it are similar to the parasites that plague their own bodies. Unfortunate consequences follow.

This is a brief story about what can happen when events are misinterpreted. The outcome is predictable. The author's use of unpronounceable alien words doesn't help. Two stars.

Goodlife, by Fred Saberhagen

This is a sequel to Fortress Ship, which recently appeared in the pages of If. Three people survive an attack on their spaceship by a gigantic warship known as a berserker. One is near death from his injuries. The computer brain of the berserker orders them to come aboard so it can study humans. They agree, desperately hoping for an opportunity to destroy the relentless machine. Living alone on the berserker is a man, conceived from cells taken from human prisoners. He has never known anything but a life of slavery, with severe punishment for failure to obey the berserker. At first, he is terrified by the arrival of other people. The berserker commands him to co-operate with them, knowing it has already deactivated the bomb they brought with them. What follows is a tense cat-and-mouse game, with the humans learning something new about the origin of the berserkers.

This is a suspenseful tale, with a great deal of insight into the psychology of the berserker's slave. His distorted view of humanity provides much pathos. The journey through the interior of the enormous machine is awe-inspiring. The ending is sudden, but otherwise satisfying. Four stars.

Science and Science Fiction: Who Borrows What?, by Michael Girsdansky

This is an informal article, which makes the obvious point that SF writers are inspired by the discoveries of science, and vice versa. It wanders all over the place, from legends of Atlantis to Project Ozma. The most interesting detail, discussed in a single paragraph, is the fact that MIT students were required to design products for an imaginary alien species. Two stars.

Far Avanal, by J. T. McIntosh

For reasons not entirely clear, the population of future Earth consists of three times as many men as women. This leads to a society in which women pick their husbands as they please, and many men go without wives. The protagonist loses his intended to another man, an event that is all too common. He receives an offer to journey to a colony planet, where the sexes are evenly matched. The drawback is that he will have to travel through space in suspended animation while decades go by. If he decides to return to Earth, an option he insists upon when he accepts the offer, he will be an anachronism, half a century out of date. Things don't turn out as expected, and he must change his assumptions about his new world and the people who inhabit it.

I have mixed feelings about this story. The premise is contrived, but the author presents the consequences of it in a convincing way. Although some of the women are selfish and vain, another is by far the most intelligent, competent, and sympathetic character in the piece. At the start, the main character is suspicious to the point of paranoia; he eventually learns to overcome his distorted view of others. This touch of psychological depth makes the story worth reading. Three stars.

The Great Slow Kings, by Roger Zelazny

Two aliens rule over their planet as monarchs, although their only subject is a robot. The sole remaining members of their species, they think, speak, and act extremely slowly. A single conversation lasts for centuries. They decide to send the robot on a spaceship in order to bring back members of another species as subjects. The relative swiftness of their captives leads to complications. The way in which the aliens have a completely different view of time than their new subjects, possibly supposed to be human beings, made this a droll little story. Three stars.

When You Giffle . . ., by L. J. Stecher, Jr.

This is the third tall tale from the captain of the starship Delta Crucis, previously seen transporting an elephant, then a cargo of valuable plants. In his wildest adventure yet, he winds up lost, in an unknown part of space. Two little boys, calmly swimming in the vacuum between the stars, help him find his way, as well as enabling him to carry a whale that is much too big to fit inside his spaceship. The children, with their god-like telekinetic abilities, may be intended as a parody of the kind of psionic supermen found in Analog. In any case, this is a silly story, providing only broad comedy. Two stars.

All We Marsmen (Part 3 of 3), by Philip K. Dick

The latest work from an author who recently won the Hugo for his novel, The Man in the High Castle concludes. This installment falls somewhere between the realistic narrative style of the first third and the jarring surrealism of the middle portion. A meeting between a schizophrenic repairman and an avaricious head of the Martian water union, which was previewed in multiple, distorted ways in Part Two, takes place. The repairman has no memory of it at all. The union leader vows to take revenge on the repairman, whom he believes failed and betrayed him. Following the advice of his Martian servant, he sets out on a pilgrimage with an autistic boy to a sacred site of the natives. His goal is to use the boy's ability to perceive and manipulate time to change the past, so he can claim ownership of a seemingly worthless piece of land, which will be valuable in times to come. The boy has a terrifying vision of his future as an old man, trapped in a nursing home, most of his body missing, kept barely alive by machines. The novel returns to its opening scene, as the union leader relives his first encounter with the repairman, and the characters meet their fates.

The climax of this complex, difficult novel is dramatic. The ambiguous nature of reality, shown through the union leader's mental journey through time, is vividly portrayed. Readers who have been patient with its downbeat mood will be pleased with a touch of hope at the end. The characters have the complicated personalities of real people. (Even the union leader, who is definitely the novel's villain, is sometimes sympathetic.) I recommend reading all three parts together. Waiting two months between installments weakens the impact of the circular structure of the plot. (If it is published in book form, perhaps the title will be changed to something more appropriate.) Four stars.

As these stories show, science fiction can help us appreciate the way that others might see reality. Perhaps, by looking through the eyes (or other sense organs) of different people (or other lifeforms) through the pages of our favorite magazines, we may come to have a empathy for those with other viewpoints, to be more tolerant of beliefs that don't match our own.

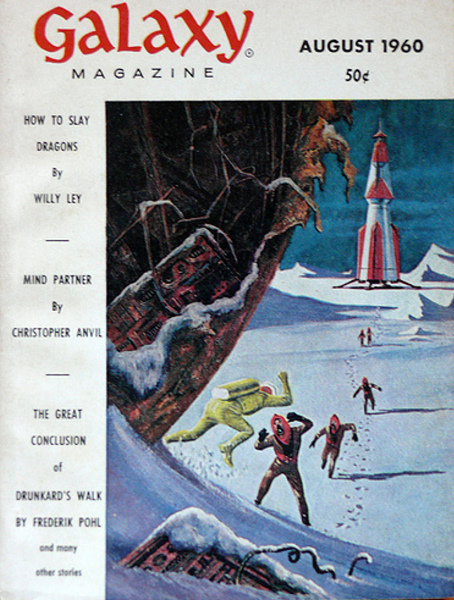

![[October 18, 1963] Points of View (December 1963 <i>Worlds of Tomorrow</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/631018cover-485x372.jpg)