[if you’re new to the Journey, read this to see what we’re all about!]

by Victoria Silverwolf

January was full of ups and downs here in the United States. Early in the month, the price of a first class stamp jumped from four cents to five cents. That's a twenty-five percent increase, and it's only been five years since the last time the cost went up.

And postcards are now four cents.

At least we could forget about inflation for a while when Leonardo da Vinci's masterpiece La Gioconda (more commonly known as Mona Lisa) was put on exhibition in the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. Thanks to the diplomatic charm of First Lady Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, the French agreed to let the most famous painting in the world travel across the Atlantic.

President Kennedy, Madame Malraux, French Minister of State for Cultural Affairs Malraux, Mrs. Kennedy, Vice-President Johnson.

Not even this great artistic event, however, could distract Americans from the most important social problem facing the nation. Because I live about twenty miles from the state of Alabama, it hit me hard when I read the inauguration speech of George C. Wallace, newly elected Governor of the Cotton State.

In the name of the greatest people that have ever trod this earth, I draw the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny and I say: segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.

Wallace delivering a speech written by Asa Carter, a member of the Ku Klux Klan.

Given this fiery defiance, I am terrified of the possibility of my country facing a second Civil War over Civil Rights.

It's understandable that, in these uncertain times, Americans turned to the soft crooning of Steve Lawrence's syrupy tearjerker Go Away, Little Girl, which hit the top of the charts this month.

Appropriately, the latest issue of Fantastic is a mixture of the good and the bad.

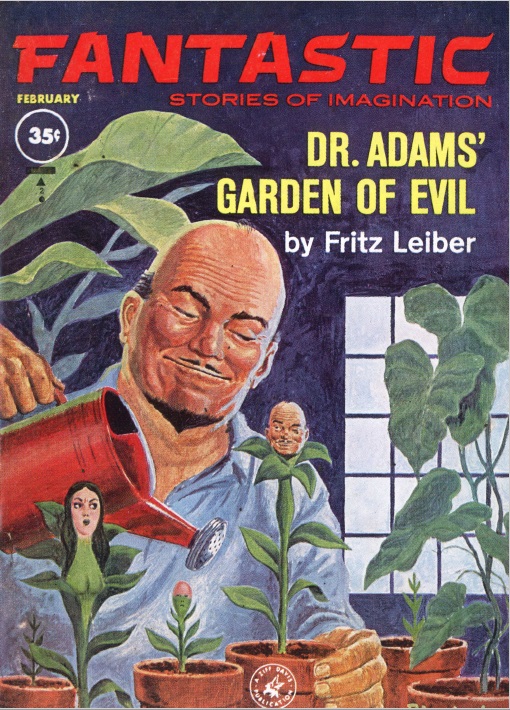

Dr. Adams' Garden of Evil, by Fritz Leiber

It seems likely that Lloyd Birmingham's bizarre cover art provided the inspiration for this strange story of supernatural revenge. The antihero is the publisher of a girlie magazine. A woman holds him responsible for the coma that robbed her sister of her mind after she was the magazine's Kitten-of-the-Month. We quickly find out that this isn't just paranoia on her part. Through methods that combine Mad Science and Black Magic, the publisher grows miniature copies of women, which have harmful effects on the real ones. He soon faces his just deserts. Stylishly and elegantly written, with a great deal of imagination, this is a weird tale that always holds the reader's attention. Four stars.

The Titan in the Crypt, by J. G. Warner

The narrator enters a labyrinth of catacombs beneath the city of New Orleans, where he witnesses arcane rituals by cultists offering a disturbing sacrifice to a gigantic idol. A horrible being chases after him as he makes his way back to the outside world. This pastiche of H. P. Lovecraft doesn't offer anything new. The best thing about it is another outstanding, if grotesque, illustration by Lee Brown Coye. Two stars.

Let 'Em Eat Space, by William Grey Beyer

This issue's reprint comes from the November 4, 1939 issue of Argosy. Two insurance investigators travel to a distant solar system in order to find out why the metabolism of everyone on Earth is slowing down. They find a planet inhabited by giant intelligent blobs, some of whom have mutated into evil creatures that prey on the others. Our pair of wisecracking heroes manage to save humanity and the aliens. This is a wild, tongue-in-cheek pulp adventure yarn with a lot of bad science. Two stars.

Final Dining , by Roger Zelazny

An artist paints a portrait of Judas, using a strange pigment he found in a meteorite. The painting has a life of its own, and tempts the painter into evil and self-destruction. This is a compelling story by a prolific new writer. It's slightly overwritten in places, and the meteorite seems out of place in a tale of pure fantasy, but otherwise it's very effective. Four stars.

The Masters, by Ursula K. LeGuin

This is only the second genre story by another promising newcomer. It takes place centuries after the fall of modern civilization. Instead of returning to a completely pre-technological society, however, the people in this post-apocalyptic world are able to build steam engines and other moderately advanced devices. The plot begins when a man undergoes a grueling initiation, allowing him to join the rigidly controlled guild of machinists. A fellow engineer tempts him to violate the rules of their order through such forbidden activities as trying to measure the distance to the Sun and using Arabic numerals. This pessimistic tale is much more original than most stories set after a worldwide disaster. Four stars.

Black Cat Weather, by David R. Bunch

Editor Cele Goldsmith's most controversial author offers a brief story set in a future where people have many of their body parts replaced with metal. A little girl not yet old enough to require such procedures, assisted by a robot, brings something from a cemetery to her father. Told in a dense style that requires close reading, this is a dark, disturbing tale. Four stars.

Perfect Understanding, by Jack Egan

A man's spaceship crashes on Mercury while racing away from hostile aliens. The ethereal beings track him down, but he captures them and forces them to reveal their secrets in a way not revealed until the end of the story. This space opera reads like something rejected by Analog. It throws in a lot of implausible details, and the twist ending is predictable. One star.

Like life in these modern times, this issue was a real rollercoaster ride. Maybe it's best to follow the advice of the old Johnny Mercer song and accentuate the positive.

[P.S. If you registered for WorldCon this year, please consider nominating Galactic Journey for the "Best Fanzine" Hugo. Check your mail for instructions…]