by Kaye Dee

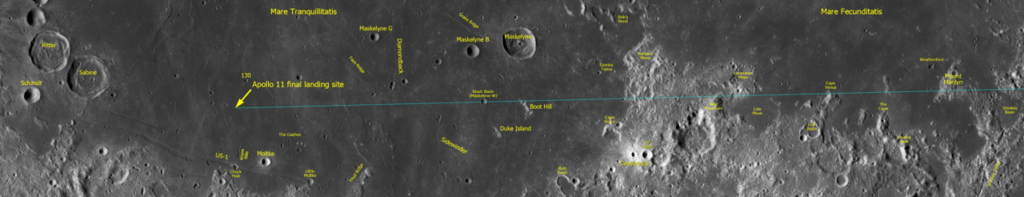

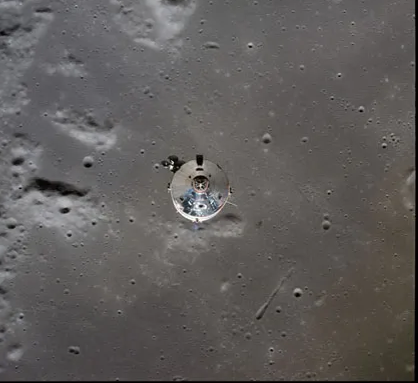

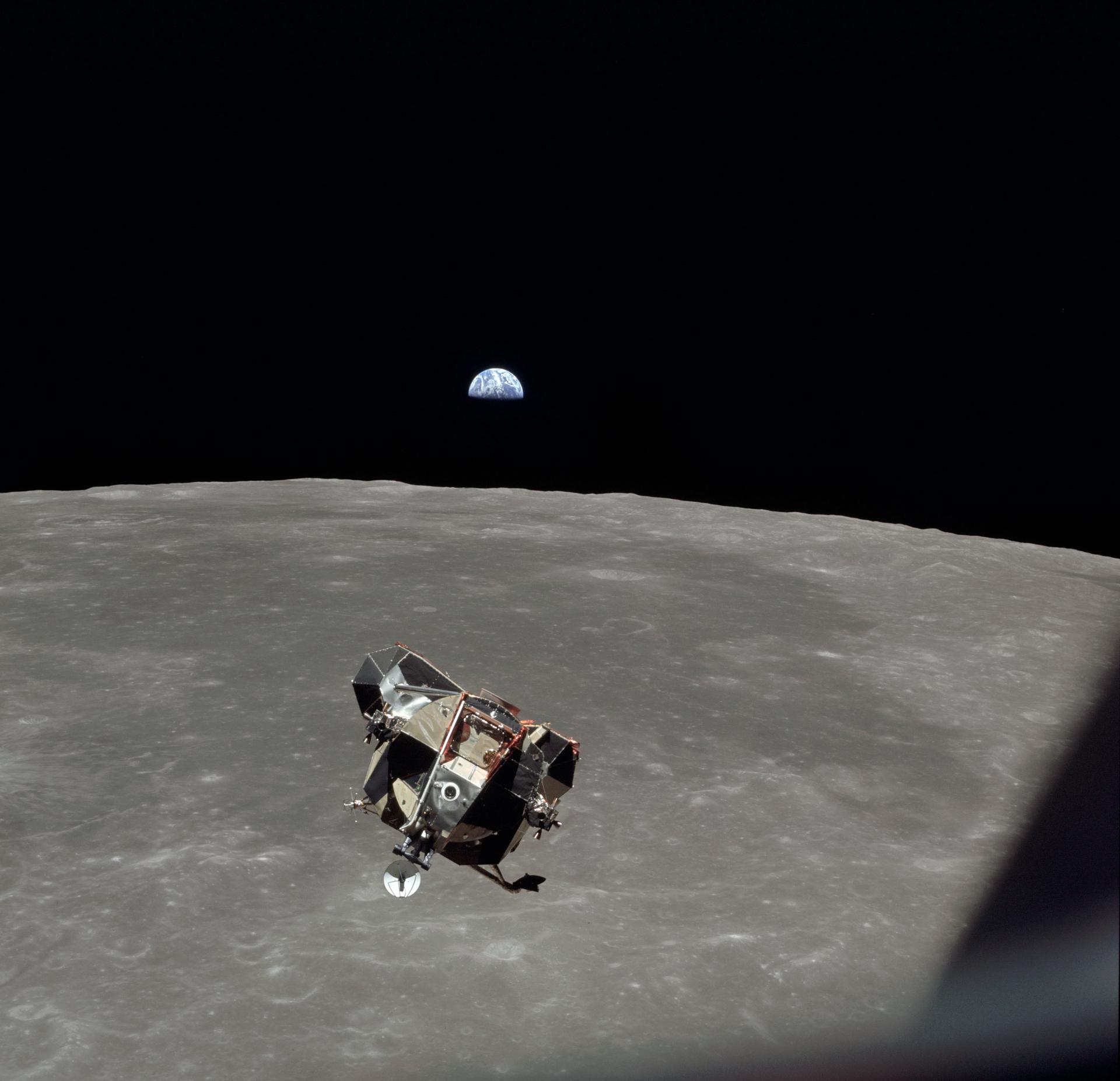

Columbia photographed over the Bay of Success in the Sea of Fertility by the LM crew before their descent to the Moon. They did not photograph the CM on their return to orbit

Columbia photographed over the Bay of Success in the Sea of Fertility by the LM crew before their descent to the Moon. They did not photograph the CM on their return to orbit

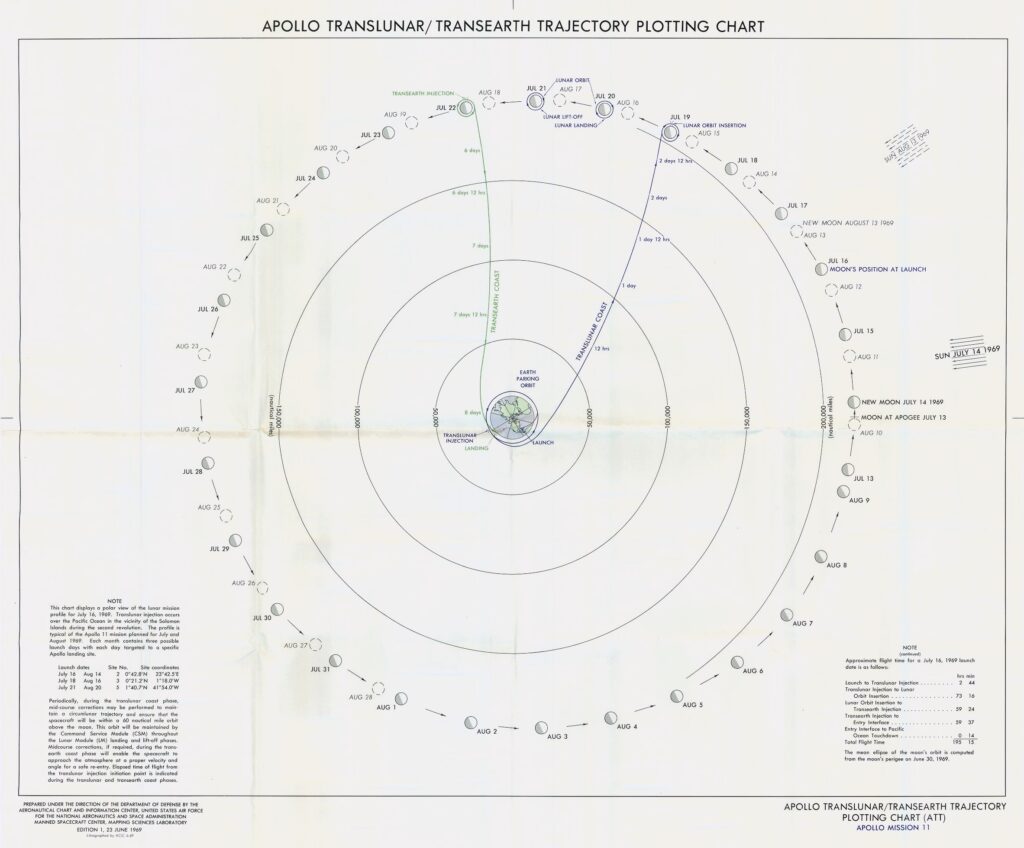

It’s hard to believe that it’s already a month since Neil Armstrong and Edwin Aldrin became the first human beings to land on the Moon – and what an eventful month it’s been for the crew of Apollo-11! It feels like this is the right time for the final part of my Apollo-11 coverage, wrapping up the final phases of the historic mission and its aftermath.

Another Giant Leap

I concluded my previous Apollo-11 article with the Lunar Module (LM) Eagle on its way to lunar orbit after a successful lift-off from the Moon’s surface. This was one of the critical stages of the mission, because if the LM’s ascent engine had failed to fire, its crew would have been stranded on the Moon – there was no back-up system. (It is rumoured that President Nixon had a suitably sombre speech prepared had the worst occurred).

I concluded my previous Apollo-11 article with the Lunar Module (LM) Eagle on its way to lunar orbit after a successful lift-off from the Moon’s surface. This was one of the critical stages of the mission, because if the LM’s ascent engine had failed to fire, its crew would have been stranded on the Moon – there was no back-up system. (It is rumoured that President Nixon had a suitably sombre speech prepared had the worst occurred).

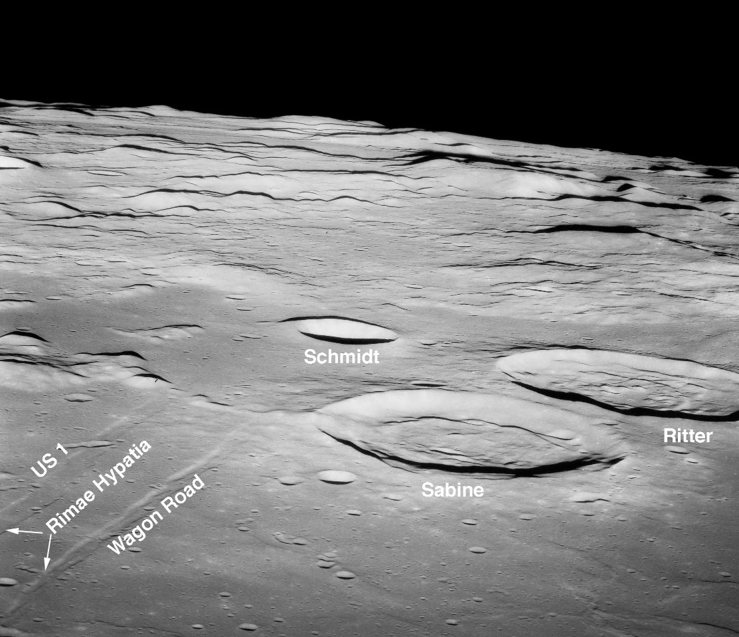

The astronauts have since reported that, as they took off, they heard no sounds in the Moon’s airless environment, but they felt the acceleration and a high frequency vibration through their feet. Seconds after liftoff, the LM pitched forward about 45 degrees, so Mr. Armstrong and Col. Aldrin could see the Moon’s surface scrolling past and receding as they leapt towards rendezvous with the Command Module (CM) Columbia in lunar orbit. As they had during the landing, Aldrin worked the computer while Armstrong flew and navigated the LM. “We’re going right down US-1,” Commander Armstrong informed Mission Control about three minutes into the flight.

All Quiet on the Orbital Front

While orbiting the Moon alone, CM Pilot Collins had a comparatively quiet time. He generally performed maintenance and “housekeeping” tasks, although on his third solo orbit a problem arose with the temperature of the environmental coolant, which might have caused parts of Columbia to freeze. Fortunately, this was soon resolved and there were no other major issues.

When the LM crew slept after their exhausting Moonwalk, so too did Col. Collins. He wanted to be well-rested for the rendezvous with Eagle , on which the next step in Apollo-11’s success would rest.

Crucial Rendezvous

Just as the separation from the CM to begin the descent to the lunar surface had occurred behind the Moon, with the astronauts out of contact with Mission Control, so to would the crucial return rendezvous between the two spacecraft.

While Columbia orbited 60 miles above the lunar surface, Mike Collins prepared for the rendezvous. Slung around his neck, he carried a book he had prepared containing 18 different rendezvous procedures – he was taking no chances at this stage of the mission! Although the flight plan called for Eagle to fly up to Columbia, if necessary Col. Collins could descend to meet the LM.

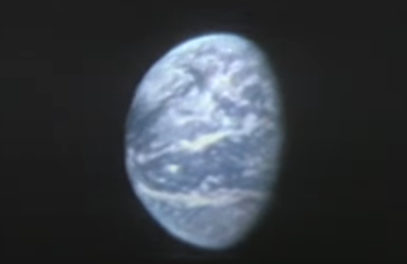

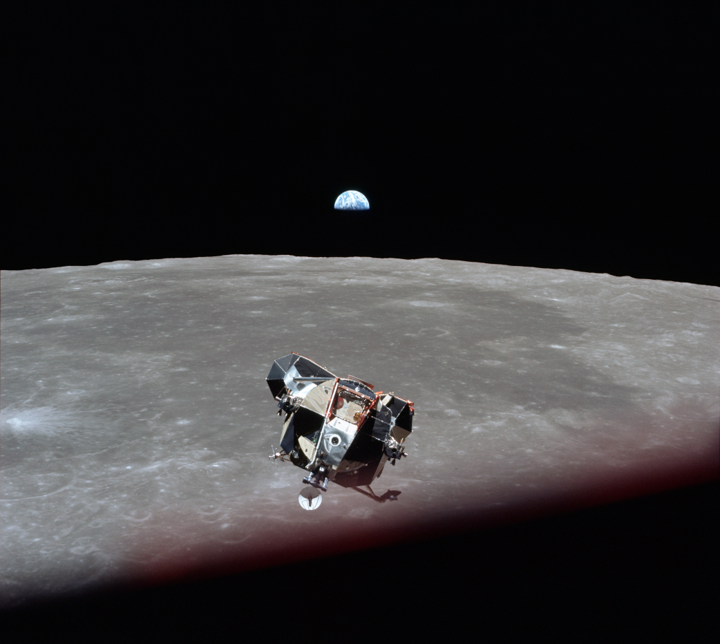

Collins' favourite photo of the images he snapped of this scene. It shows the Earth, Moon, LM and the CM window frame, thus capturing all four players in the mission in one image

Collins' favourite photo of the images he snapped of this scene. It shows the Earth, Moon, LM and the CM window frame, thus capturing all four players in the mission in one image

Eagle fortunately encountered no problems during its ascent to orbit. As the two spacecraft came around the Moon and back into contact with Mission Control, Col. Collins captured yet another magnificent sight: the Moon, Earth, and returning Ascent Stage of the LM approaching him, all in one picture.

Duelling Vehicles

Mr. Armstrong took up a station-keeping position just 50 ft from the CM. Then the three astronauts prepared for the critical re-docking. At 128:03:00 Ground Elapsed Time (GET), the two spacecraft gently connected, so smoothly that Col. Collins said he did not even feel the docking latches snap together.

However, moments later, the astronauts were jolted as the joined vehicles began to jerk around, with both the LM and CM firing their thrusters! What was happening? It seems that the automatic attitude systems on both spacecraft were competing with each other to control the attitude of the docked vessels! Fortunately, when the Eagle’s automatic pilot was switched off the problem disappeared.

Together Again

Despite that unexpected incident, the Apollo-11 crew were safely back together again, just three minutes behind the time specified by the original Flight Plan! Col. Aldrin was the first through the hatch into the CM, followed by mission commander Armstrong, and an excited reunion took place.

The precious 47lbs of lunar samples were transferred to Columbia, along with the still and movie camera film magazines and some other equipment. Two hours after the docking, the Eagle was jettisoned into lunar orbit in preparation for the return to Earth. Mr. Armstrong commented, “The separation was slow and majestic; we were able to follow it visually for a long time” (although Col. Collins forgot to film it as had been intended).

On Their Way Home

One orbit later, behind the Moon, at 135:23:42 GET, Apollo-11 fired the Service Module’s motor for 2 minutes 31.41 seconds to set them on a safe course for home at an initial speed of 5856 miles per hour. The Command Service Module (CSM) had completed 30 orbits of the Moon in 59 hours 30 minutes 26 seconds.

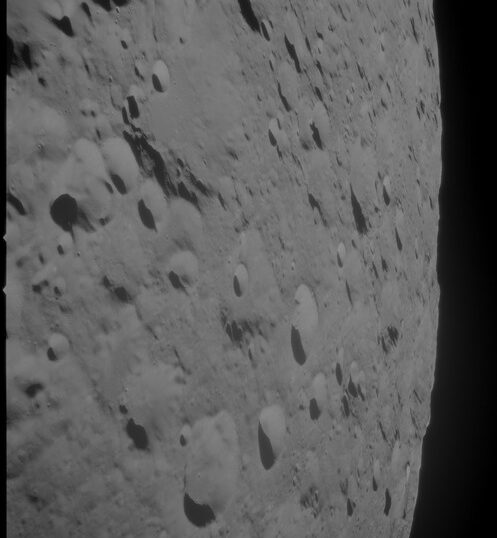

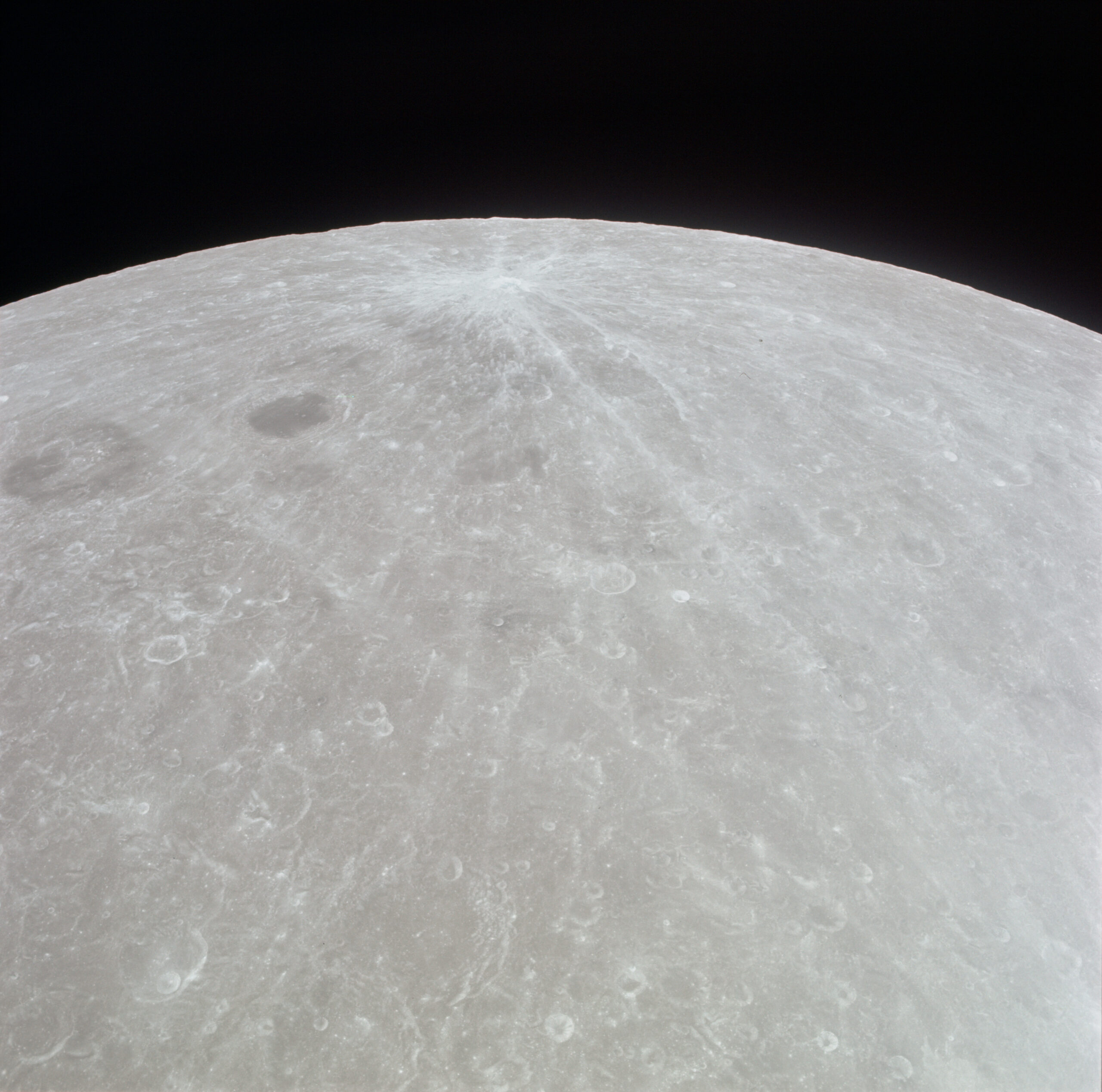

View of Lomonosov and Joliot craters, taken after Apollo-11 was en-route for Earth

View of Lomonosov and Joliot craters, taken after Apollo-11 was en-route for Earth

As the Moon quickly receded behind them, the Apollo-11 crew snapped many pictures of it to use up some of their film, and then took the time for some much-needed rest, sleeping for about ten hours. Waking at 147:37:00 GET, they passed through the gravity hump between the moon and Earth about 30 minutes later, as they ate their breakfast 200,000 miles from the Earth and 39,000 miles from the Moon.

View of the receding Moon 1922 miles behind Apollo-11

View of the receding Moon 1922 miles behind Apollo-11

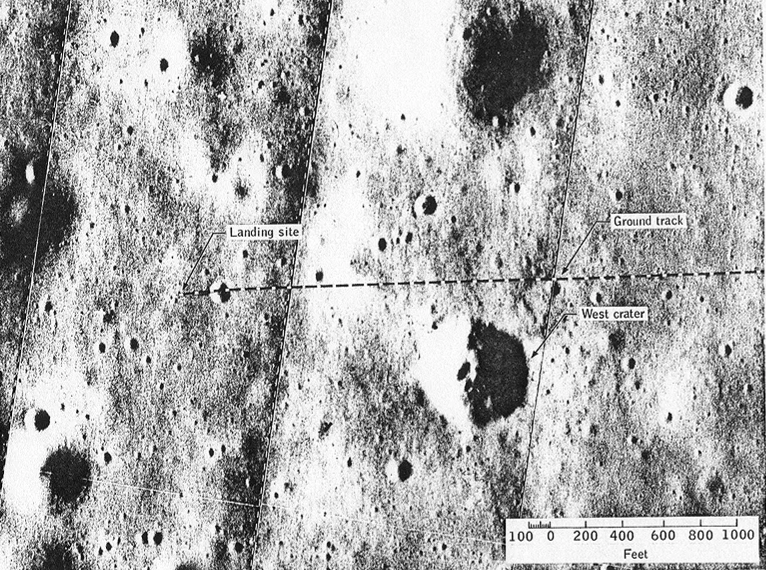

Pinpointing the Landing Site

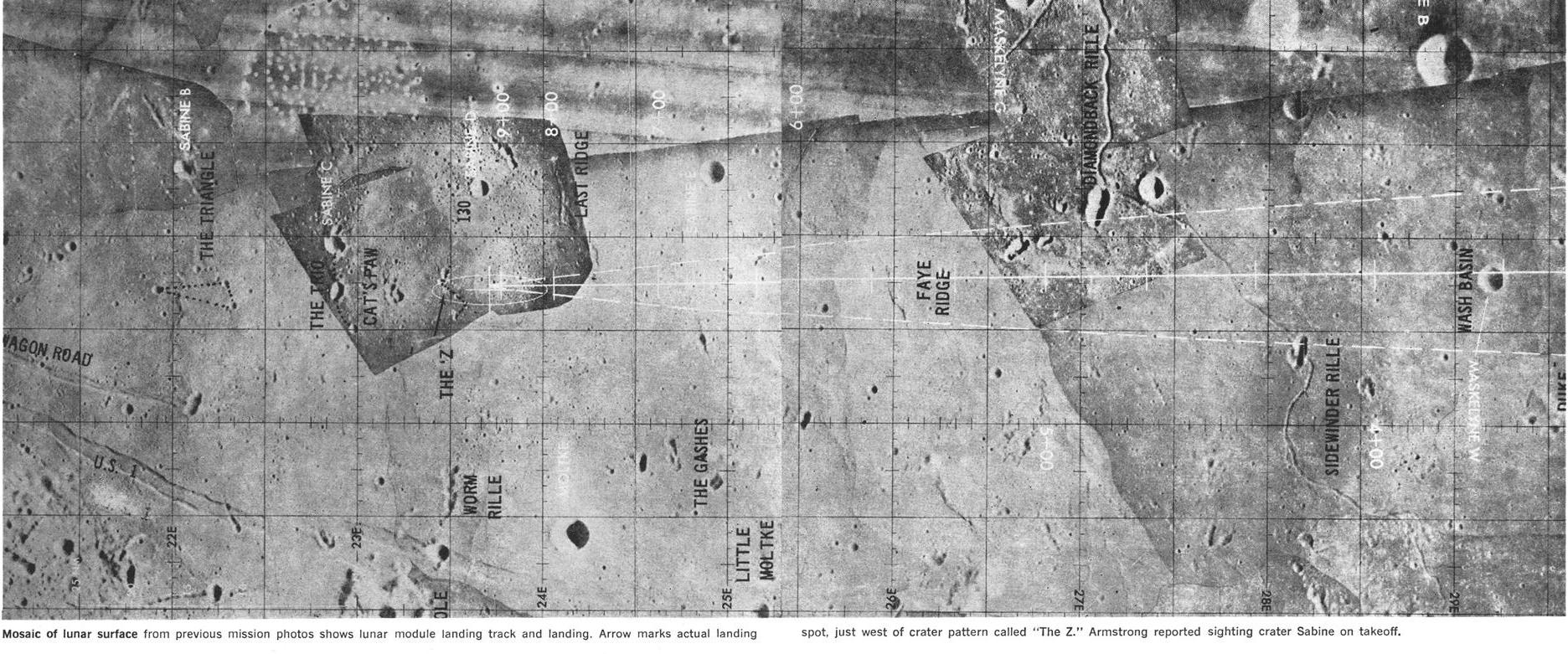

I mentioned in Part 2 that, because Commander Armstrong had to overfly the originally planned landing site to find safer terrain on which to put the LM down, the exact site of Tranquillity Base was uncertain. As they were returning to Earth, Mr. Armstrong made a casual remark during a debriefing that finally helped to pinpoint the exact location.

“I took a stroll back to a crater behind us that was maybe seventy or eighty feet in diameter and fifteen or twenty feet deep and took some pictures of it. It had rocks in the bottom….”

While that might not sound like much to those of us who are not geologists, it was just the description NASA’s lunar mapping team needed to identify the landing spot on their maps – an identification later confirmed by the 16mm film of the landing. We now know that Tranquillity Base is located at 0° 41'15" North latitude, 23° 25'45" East longitude. If only Armstrong had mentioned that crater before!

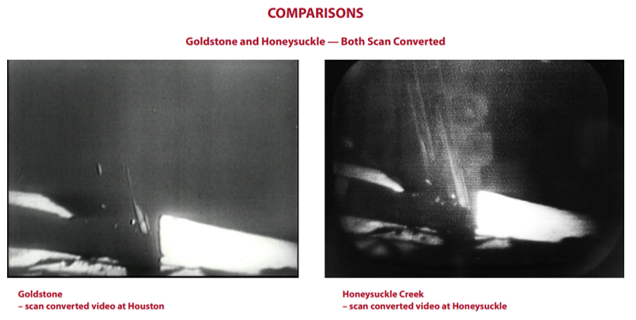

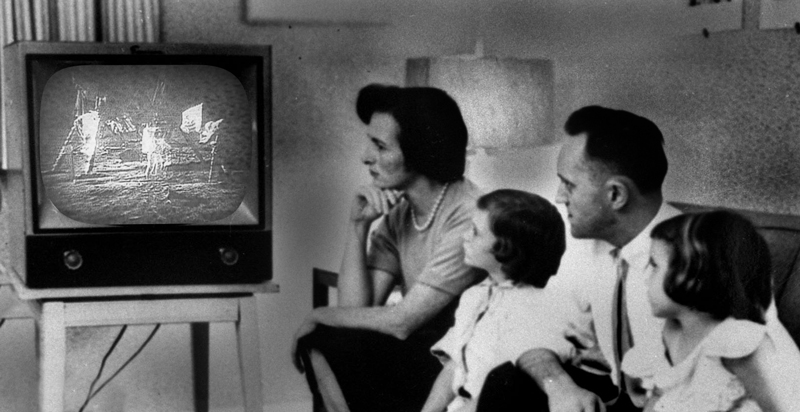

The Apollo-11 Show

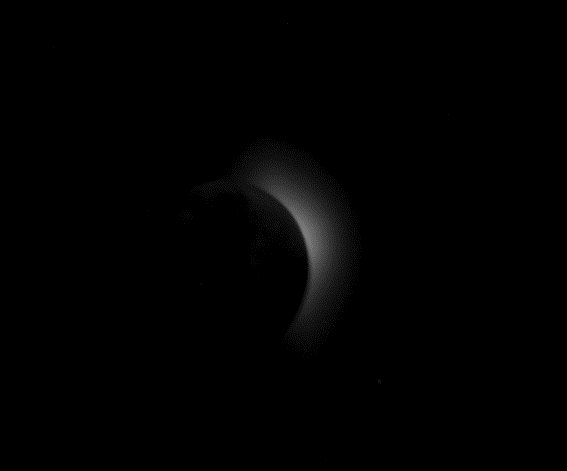

At 155:36:00 GET the Apollo-11 crew presented an 18 minute television broadcast. The show began with views of the Moon, and Capcom Duke in Mission Control generated some amused banter when he misidentified the image of the Moon on his monitor as the Earth!

Would you mistake this Moon for the Earth? The image quality of the monitor Charles Duke was looking at was apparently very poor!

Would you mistake this Moon for the Earth? The image quality of the monitor Charles Duke was looking at was apparently very poor!

Mr. Armstrong showed the boxes of lunar samples and explained that they were vacuum packed on the lunar surface. Col. Aldrin provided a quick history of space food, showed how to make a weightless ham-spread sandwich, and then demonstrated the physics of gyroscopes (a lot more fascinating than reading it in a textbook).

For “all you kids” on Earth, Col. Collins showed how water clings to a spoon in zero-g, before demonstrating how the crew actually drank water using a water gun. The broadcast finished with a view of the approaching Earth.

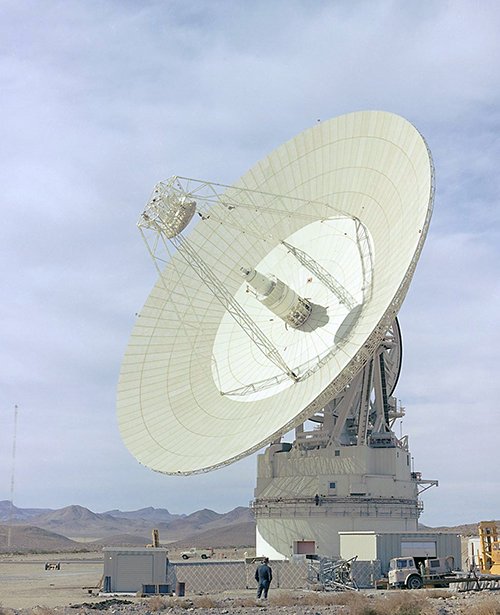

Greg Saves the Day

As Apollo-11 sped towards the Earth, the Manned Space Flight Network tracking station in Guam, due to play an important role in the final stages of the mission, had a problem. A bearing seized from lack of grease had immobilised the antenna. A normal repair would take too long, and only a narrow hole could provide access for a quick fix—too small for the staff to reach the bearing through it.

View of the Guam Manned Space Flight Network Station

View of the Guam Manned Space Flight Network Station

Eventually, Station Director Charles Force drafted his ten-year-old son, Greg, to help. The boy was able to slip his hand into the small opening and pack the bearing with grease, enabling the antenna to move again so that the station could continue its tracking support. I’m told that Neil Armstrong intends to thank Greg personally when the Apollo-11 crew visits the Guam station to thank the team for their mission support work. I'm sure it will be a wonderful surprise for the lad.

A Thoughtful Final Broadcast

Commencing at 177:32:00 GET, 105,150 miles from Earth, the Apollo-11 astronauts gave the final television broadcast of their mission, which began by referencing Jules Verne's "Del la Terre a la Lune" (From the Earth to the Moon) and included thoughtful commentaries on the contribution of the hundreds of thousands behind the scenes whose work had helped to make the mission a success. This was very much in keeping with the spirit in which the crew decided not to include their names on their mission patch, so that it could symbolise everyone involved.

Col. Collins pointed out the number of components involved in the Apollo spacecraft and expressed the crew’s confidence in their reliability. He likened the mission to the periscope of a submarine. “All you see is the three of us, but beneath the surface are thousands and thousands of others, and to all those, I would like to say thank you very much.”

During his talk, Col. Aldrin expanded on this idea: “We have come to the conclusion that this has been far more than three men on a voyage to the Moon. More still than the efforts of one nation. We feel that this stands as a symbol of the insatiable curiosity of all Mankind to explore the unknown.”

Finally, Mr. Armstrong concluded the broadcast with this tribute: “The responsibility for this flight lies first with history and with the giants of science who have preceded this effort. Next with the American people, who have through their will, indicated their desire. Next to four administrations and their Congresses for implementing that will. And then to the agency and industry teams that built our spacecraft […]. We would like to give a special thanks to all those Americans who built those spacecraft, who did the construction, design, the tests and put their their hearts and all their abilities into those craft.

"To those people tonight, we give a special thank you, and to all those people that are listening and watching tonight, God bless you. Good night from Apollo 11.”

View of the Earth from around 100,000 miles taken about an hour after the final television broadcast

View of the Earth from around 100,000 miles taken about an hour after the final television broadcast

Returning to Earth

As I’ve noted before, the entry corridor into the Earth’s atmosphere when returning from the Moon is extremely critical: too steep an entry would cause the spacecraft to burn up, while too shallow an entry would make it skip off the atmosphere and out into solar orbit, to be lost forever. Apollo-11’s re-entry corridor was 40 miles wide, and they would be coming in at 24,680mph! Consequently, before re-entry, the Apollo-11 crew jettisoned the Service Module at 189:28:35 GET, to re-enter and burn up separately. The 4.8 (imperial) ton Command Module would be the only part of the original 3,148-ton Apollo-Saturn vehicle that made this historic lunar voyage that returned to Earth.

Apollo-11's Service Module disintegrates and burns up on re-entry. This photo was captured by a NASA ARIA tracking aircraft

Apollo-11's Service Module disintegrates and burns up on re-entry. This photo was captured by a NASA ARIA tracking aircraft

Re-entry commenced at 400,000ft, with the CM becoming engulfed in a fireball as it hit the denser air. The effects of gravity and deceleration subjected the Apollo-11 crew to stresses of up to 6.5g.

Skipping Home

Prior to re-entry, the astronauts had been informed that their splashdown point was being shifted 215 nautical miles due to a dangerous thunderstorm in the planned recovery area. This required the CM to make one final manoeuvre during re-entry to target the new splashdown site, about 1,000 miles south-west of Honolulu.

The gumdrop-shaped Command Module has a slight aerodynamic lift capability, and this was used to "fly" the extra distance downrange, by generating two short atmospheric “skips” (ones that would not cause the CM to fly off into space again!) during the re-entry.

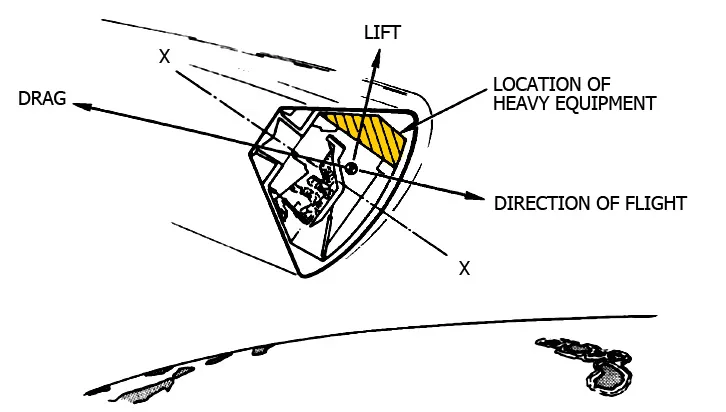

Diagram showing how the CM's offset centre of mass results in a lift vector during entry, which provides the CM with some manoeuvrability

Diagram showing how the CM's offset centre of mass results in a lift vector during entry, which provides the CM with some manoeuvrability

Then, right on time at 195:12:06 GET, the small drogue parachutes deployed, hauling out the three main orange-and-white striped parachutes and allowing Columbia to float gently down towards the Pacific Ocean.

Splashdown!

Dawn was just breaking as Columbia descended towards the recovery area, where 9,000 men in nine ships and fifty-four aircraft, spearheaded by the aircraft carrier USS Hornet, were waiting. 11 miles away from the Hornet, the spacecraft splashed down in the inverted position known as the Stable 2. In this position, the heavy side of the spacecraft goes downward leaving the hatch facing upwards, while the crew are upright but hanging forward in their harnesses at about 45°.

A low-resolution night vision camera image of the Apollo-11 splashdown, captured by a recovery helicopter. It is the only known image of this event

A low-resolution night vision camera image of the Apollo-11 splashdown, captured by a recovery helicopter. It is the only known image of this event

The historic first lunar landing mission came to an end at 195 hours, 18 minutes 35 seconds GET, 7.50am local Hawaii time on Thursday 24 July (2.50am 25 July for us here in Australia). Amazingly, and a tribute to the mission planners, this was just 24 seconds ahead of the time specified in the original flight plan! The return voyage from the Moon had taken 59 hours 36 minutes 52 seconds.

Taken some minutes later, when the daylight has increased, this photo shows the CM still in the inverted Stable 2 position

Taken some minutes later, when the daylight has increased, this photo shows the CM still in the inverted Stable 2 position

It took the floatation bags almost 8 minutes to flip the CM the right way up (Stable 1 position), which allowed the frogmen recovery crews to access to the spacecraft hatch. Although the waves were only about three or four feet, rumour has it that the astronauts were glad they had taken the precaution of swallowing seasickness tablets before re-entry commenced!

Returning Heroes – and Biological Hazards!

Although it has been generally accepted for some time that the Moon is likely a dead and sterile world, an overabundance of caution encouraged the treatment of the returning astronauts, their spacecraft and the lunar samples, as potential biological hazards – just in case there is some unknown form of microbial life on the Moon that might be pathogenic to Earthly lifeforms.

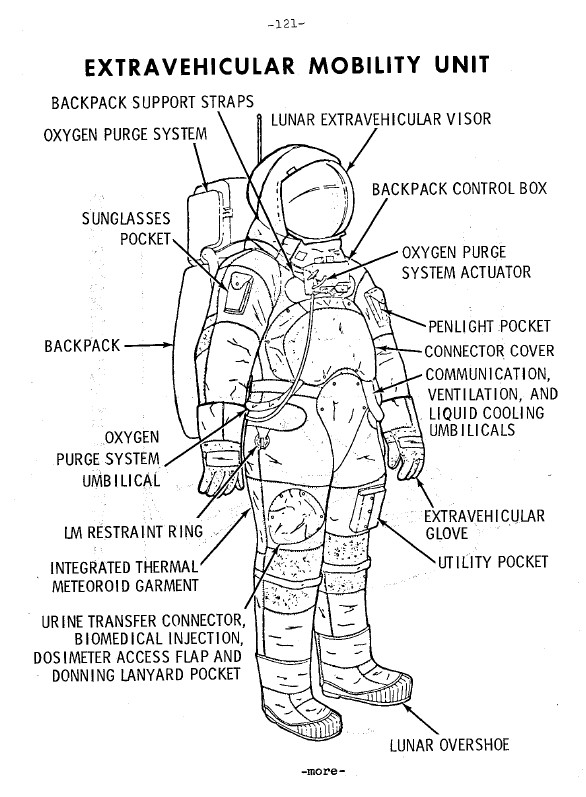

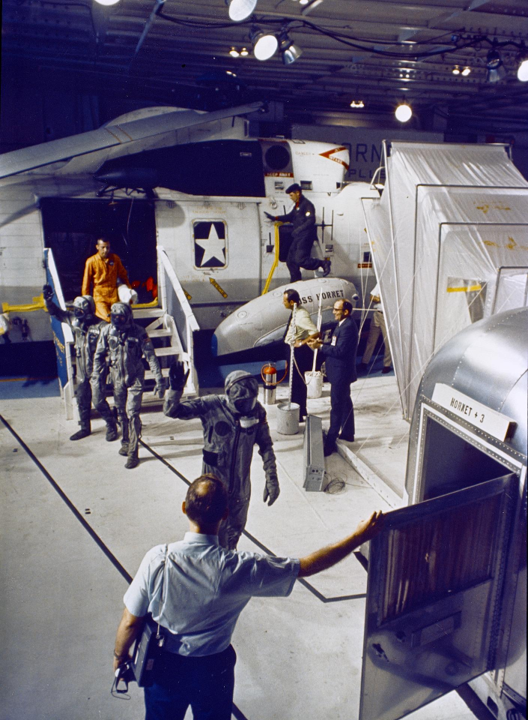

So while the Apollo-11 crew may have returned to Earth as heroes for accomplishing the first successful lunar landing, they were initially treated in a most unheroic way – as potential carriers of contagion! Biological Isolation Garment (BIGs) were tossed through the CM hatch to the astronauts by one of the recovery frogmen. Then, looking like aliens themselves in their masked isolation garments, the astronauts exited the hatch and climbed into a rubber dinghy, spraying each other down with Sodium Hypochlorite.

A recovery helicopter then transferred Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins to the Hornet, where they were immediately installed in the Mobile Quarantine Facility (MQF), a converted Airstream caravan in which they would spend the next three weeks in isolation, supported by volunteer medical personnel. As they set foot on the deck of the Hornet, its band – at President Nixon's request, in honour of the crew and their spacecraft – played "Columbia, Gem of the Ocean".

It was here that President Nixon, who had travelled to the recovery zone to greet the returning astronauts, welcomed the historic crew back to Earth standing outside the MQF’s viewing window.

President Nixon and the Apollo-11 crew in quarantine bow their heads as the USS Hornet's chaplain offers a prayer of thanksgiving for their safe return

President Nixon and the Apollo-11 crew in quarantine bow their heads as the USS Hornet's chaplain offers a prayer of thanksgiving for their safe return

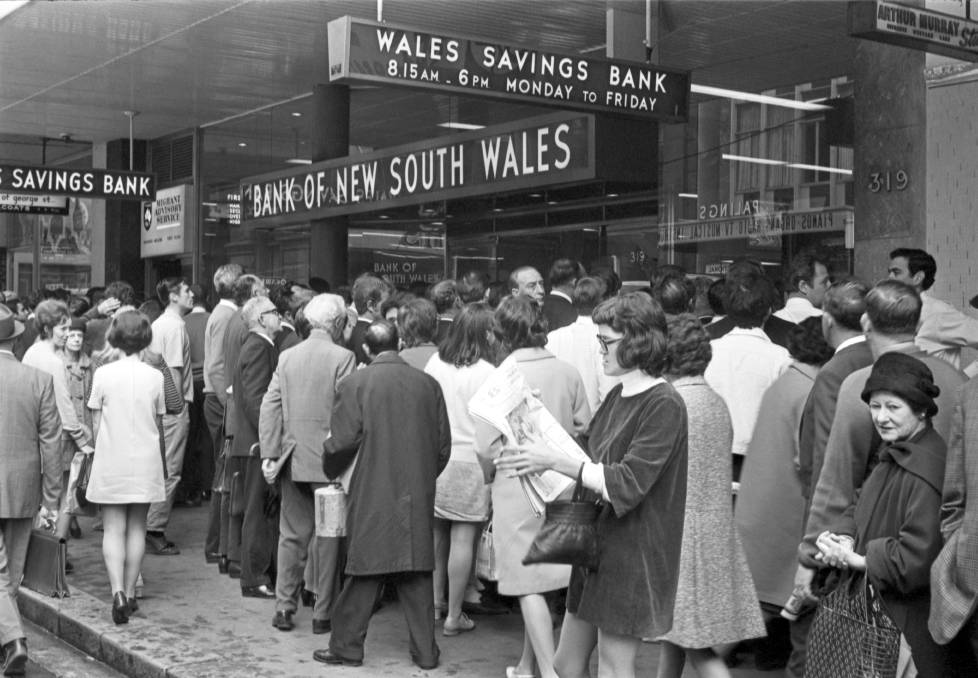

Mission Control Celebrates

As the big screens in Mission Control displayed televised images of Columbia floating safely in the Pacific swell, the room erupted in celebration! Excited flight controllers and NASA officials waved flags and smoked the traditional splashdown cigars. When the news came that the astronauts were safely on board the USS Hornet and Mission Control’s responsibility was over the euphoria became even more fervent. It was especially satisfying for them to have met President Kennedy’s deadline and a new image flashed up on the big screen, saying “Task accomplished July, 1969”.

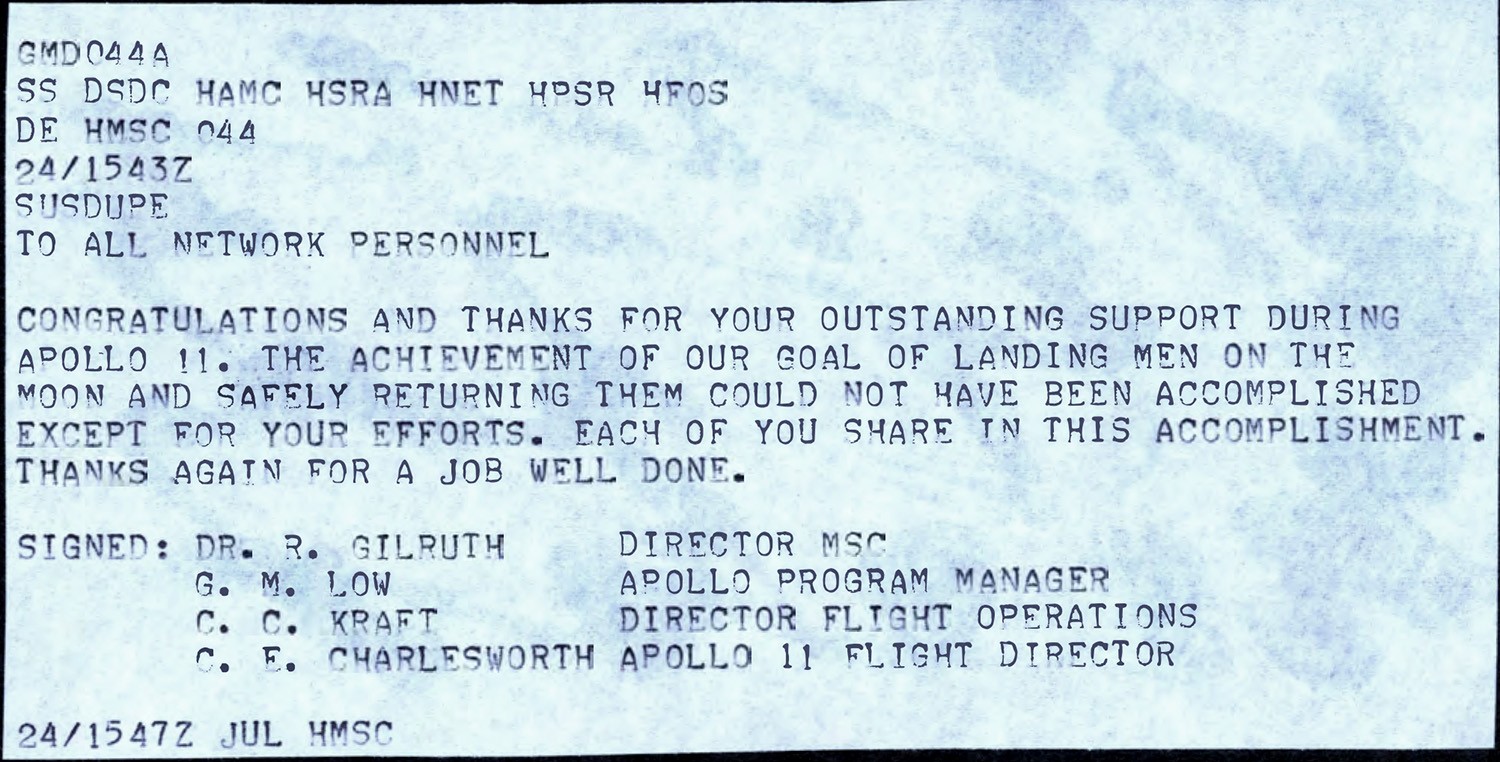

Congratulatory messages were also sent to the tracking stations around the word that had supported the Apollo-11 mission. Their personnel, too, felt a deep pride in the accomplishment, and their part in it.

The Last Leg of Columbia’s Journey

With its crew whisked away to quarantine, Columbia, bobbing in the ocean, was scrubbed down with Betadyne by the recovery crew, to kill any external contamination it might be carrying. It was then winched aboard the USS Hornet and positioned next to the MQF, so that the two could be connected by a flexible tunnel. This allowed the retrieval of the Moon rocks and other items into the MQF without contaminating the surrounding environment. Like the crew, the interior of the CM was ‘in quarantine’ for 21 days.

After the Hornet docked at Pearl Harbor on 26 July, NASA engineers saved the spacecraft at Ford Island in Honolulu, removing any residual thruster propellants and other hazardous materials before it was transferred by cargo plane to Houston for quarantine in the Lunar Receiving Laboratory (LRL) in Building 37 of the Manned Spacecraft Centre (MSC).

Columbia finally left the confines of the LRL on 14 August, to be sent back to its manufacturer, North American Rockwell, in Downey, California. Engineers are currently giving her a thorough inspection. Once this is completed, Columbia will be sent to the Smithsonian Institution where this historic spacecraft will eventually be displayed.

Moon Rock Movements

Apollo-11’s lunar samples, literally priceless in both scientific and monetary terms, have made their own separate journey to the LRL in Houston.

After being retrieved from Columbia into the MQF, the sealed boxes were released to NASA officials via the MQF’s transfer lock. Within a few hours of splashdown, the first box of Moon rocks was flown from the USS Hornet to the US Air Force base at Johnston Island in the Pacific, where it was transferred to a cargo plane and sent on to Houston. Just eight hours later it arrived at Ellington Air Force Base near the Manned Spacecraft Centre, from which the container was ferried by two NASA officials to the LRL.

Less than 48 hours after splashdown, the first box of precious lunar samples was opened inside a glovebox at the LRL, and its contents began to be documented. I’m delighted to note that New Zealand-born Australian National University geochemist, my friend Prof. Ross Taylor, has played a significant role in setting up the chemical analysis section of the LRL and is right now carrying out the first emission spectroscopy analysis of Apollo-11’s samples.

Prof. Ross Taylor (left) carrying out an analysis of an Apollo-11 sample at the LRL using an emission spectrograph

Prof. Ross Taylor (left) carrying out an analysis of an Apollo-11 sample at the LRL using an emission spectrograph

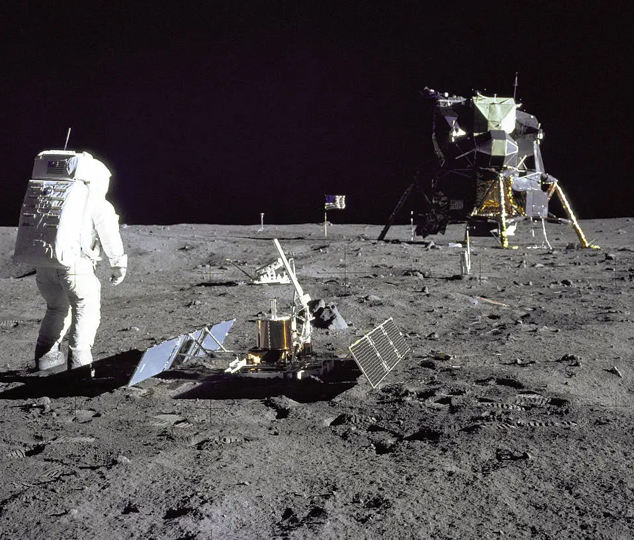

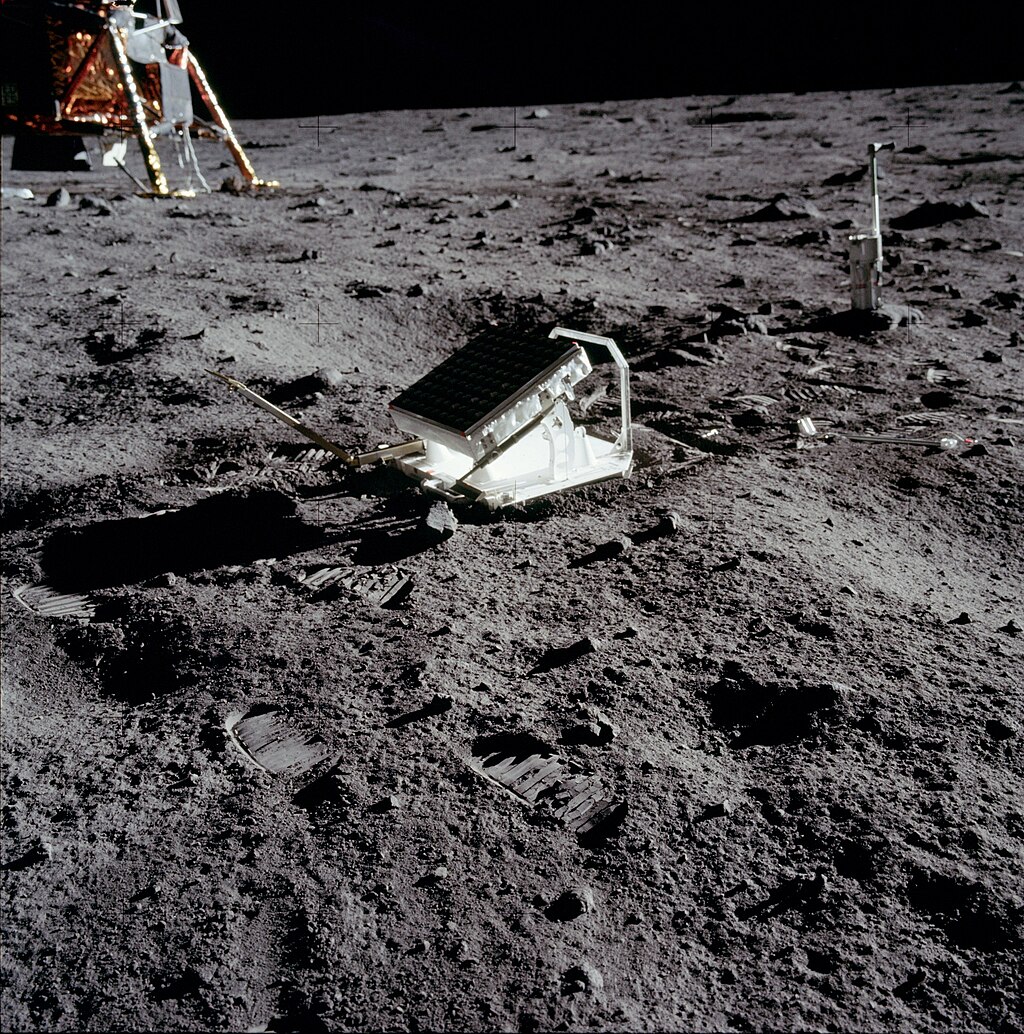

While his results are not yet available, the initial findings from other parts of the lab indicate that the lunar rocks are igneous in origin and point to past, if not current, volcanic activity on the Moon. Coupled with some early detections from the seismograph that was left on the Moon as part of the EASEP instruments, some geologists are suggesting that this provides evidence for the Earth and the Moon having a common origin.

Other initial findings are that there is very little evidence of water, and no indications of life in the lunar rocks and regolith, and that the regolith itself contains unusual microscopic spherical glass particles. Dating of some of the samples suggests they could be around 3.6 billion years old, which is the estimated age of the Solar System and the discovery of such ancient rocks has surprised many geologists.

Mice and other animals and plants exposed to lunar materials have so far shown no signs of infection or disease, and neither have the Apollo-11 crew, who were released from quarantine on August 11, leading NASA to indicate that it will generously distribute samples of lunar materials to researchers around the world in September.

A Long Journey Home for the Astronauts

With the Apollo-11 crew confined in the MQF, once the USS Hornet arrived at Pearl Harbour a crane carefully lifted the quarantine facility and its human occupants from the aircraft carrier onto a flat-bed trailer. After a brief welcoming ceremony, the MQF was transported to Hickam Air Force Base, from where it was flown to Houston.

Despite the 2am arrival on July 27, the astronauts’ wives and children were there to welcome them home, along with a large crowd of well-wishers. From inside the MQF, the astronauts could talk with their families by telephone and see them through the window, but a more affectionate homecoming was still weeks away. The MQF was then transferred to the LRL, where the sealed Crew Reception Area (CRA) provided more expansive living and working quarters for the Apollo-11 astronauts for the duration of their quarantine.

Although confined to the CRA, Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins were not idle, writing their mission reports, and conducting press conferences and mission debriefings from a glass-enclosed conference room. Their health was monitored on a daily basis, without the astronauts ever showing any signs of illness or ill-effects from their sojourn on the lunar surface. They even celebrated Armstrong’s 39th birthday with a surprise party!

On the evening of 10 August, Mr. Armstrong, Col. Aldrin and Col. Collins were finally released from quarantine, stepping out of the CRA to be welcomed by NASA officials and large number of reporters before they were whisked away home by car for long-awaited reunions with their families.

Instant Celebrities

After a day of relaxation at home, the Apollo-11 crew faced a packed press conference on 12 August, where they were greeted with a standing ovation. Referring to the Apollo programme as a “great adventure”, the astronauts spent 45 minutes describing their historic mission in great detail and illustrating it with photographs and film clips taken during the flight. Among the questions they then received from the reporters, Armstrong was asked whether he believed that one day women could become astronauts, to which he promptly replied, “Gosh, I hope so!”

The next day, at the invitation of President Nixon, the astronauts and their families embarked on a day-long whirlwind celebratory tour across the United States, travelling on the presidential jet for the occasion.

From Ellington Air Force Base they flew to New York City, where they were treated to the “largest, longest, and loudest” tickertape parade in the city’s history, with an estimated four million people lining the parade route. After being awarded the gold medal of New York City, the astronauts continued to the United Nations, where UN Secretary General U Thant welcomed them, and they made a brief speech.

Whisked from New York to Chicago, this time around two million people turned out to see the Apollo-11 crew in a tickertape parade through Chicago’s downtown. At the Civic Centre Plaza, a crowd estimated at 100,000 saw the astronauts made honorary citizens of the city, before a final stop on the way back to the airport, at which they addressed a crowd of 15,000 young people.

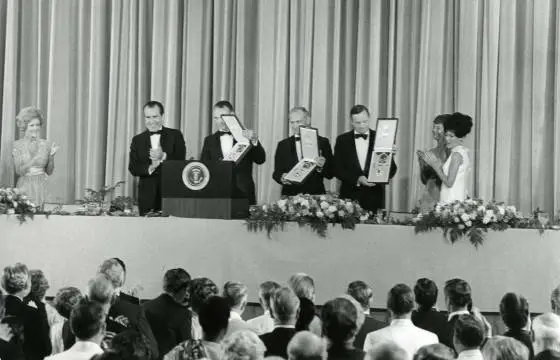

The final leg of this exhausting day was a visit to Los Angeles, to attend a state dinner hosted by President Nixon, the first ever to be held outside of Washington, DC. 1,440 guests assembled for the event, including the President and Vice President and their families, 14 members of the President’s Cabinet, 44 Governors, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, 50 members of Congress, NASA Administrator Thomas Paine and 48 astronauts, ambassadors from 83 countries and numerous Hollywood celebrities – it seems that everyone wants to meet the Apollo-11 astronauts!

Apollo-11 crew and their wives with Vice-President Agnew, President Nixon, and their wives at the Los Angeles gala

Apollo-11 crew and their wives with Vice-President Agnew, President Nixon, and their wives at the Los Angeles gala

Those of you in the US were, I understand, able to see this dinner televised live, which must have been an interesting show. Fittingly, Guidance Controller Steve Bales, who had given the Moon landing the “Go” to proceed despite the guidance computer’s programme alarms, accepted a NASA Group Achievement Award on behalf of the entire flight operations team. President Nixon also presented Mr. Armstrong, Col. Aldrin, and Col. Collins with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the United States’ highest civilian honour.

The Price of Fame

The following day, accompanied by NASA Administrator Paine, the astronauts and their families flew back to Houston aboard the presidential jet, but it seems their post-flight celebrity is only ramping up. On 15 August the Apollo-11 crew taped a major television interview, during which Col. Collins announced his decision that he would remain with NASA but make no more space flights. The next day, Houston turned on its own welcome for the astronauts with another tickertape parade, attended by about 250,000, followed by a barbecue for an estimated 50,000 invited guests, MC’d by Frank Sinatra.

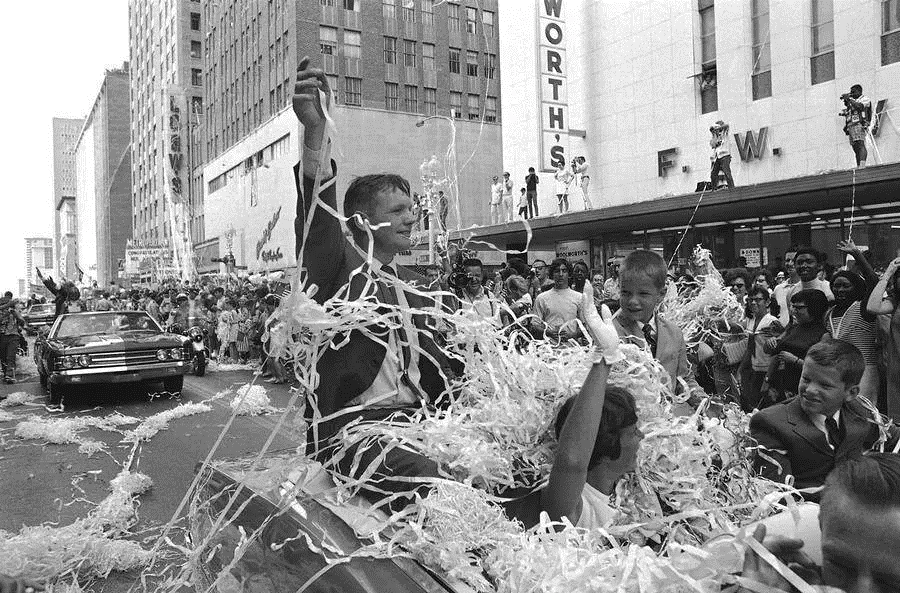

Neil Armstrong and his wife Jan buried in tickertape during the Houston parade

Neil Armstrong and his wife Jan buried in tickertape during the Houston parade

The Apollo-11 astronauts are not only American heroes, they are also heroes to the world, and the United States intends to use that fame by sending the crew and their families on a global goodwill tour next month. I just hope that they can cope with the hectic pace of their new-found celebrity – I know I wouldn’t have the stamina for such an intense schedule of public appearances – and that the price of this fame will not be too high for the astronauts' families and their marriages.

During the state dinner in Los Angeles, Col. Aldrin summed up the significance of Apollo-11 saying, “The footprints on the Moon are a true symbol of the human spirit… they show we can do what we want to do, what we must do, and what we will do…”

I think those words make a fitting conclusion to my series of articles on Apollo-11, so I’ll sign off here and leave you all to reflect on this momentous and historic mission.

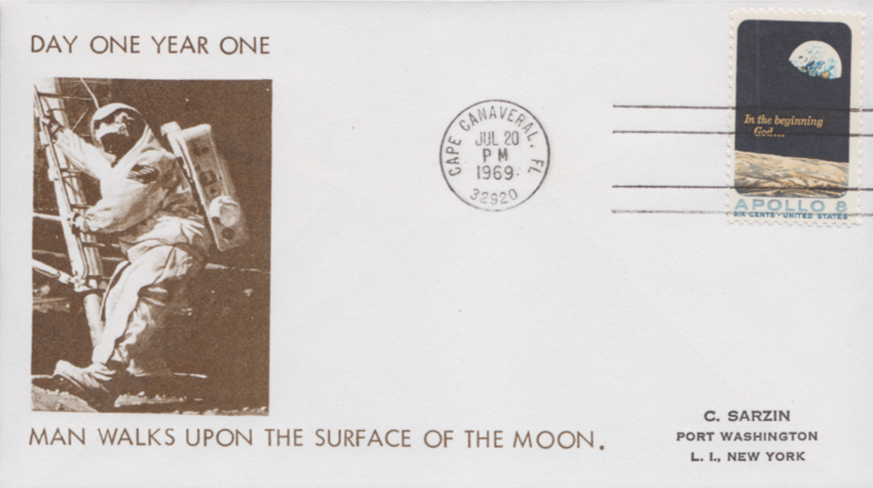

First day cover celebrating the suggestion that the day of the Moon landing becomes Day One of a new universal calendar!

First day cover celebrating the suggestion that the day of the Moon landing becomes Day One of a new universal calendar!

![[August 20, 1969] Hail Columbia! (Apollo-11, Part 3)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Apollo-11-Mission-Control-celebrates-2-551x372.jpg)

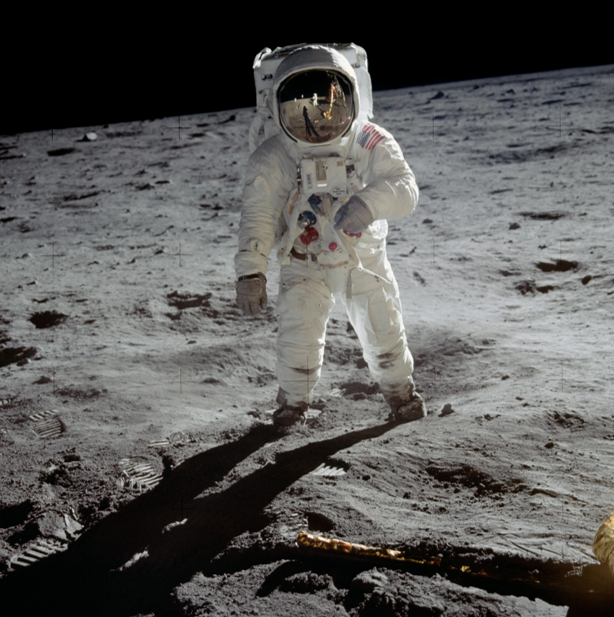

![[August 4, 1969] A Small Step and a Giant Leap (Apollo-11, Part 2)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Apollo-11-Aldrin-on-Moon-614x372.png)