Today's article is about second chances.

The newspapers are full of scary news these days. Overpopulation. Tension between the East and West. The threat of global disaster. Some feel that we are headed toward a doomed future, one of increased authoritarian governments, of scarcity, of rationing. That we lost something when the last frontiers closed, forcing us to turn inward, toward oblivion.

Poul Anderson's just come out with a new book along those lines: Orbit Unlimited. It's a fix-up of sorts, composed of four stories, two of which I've reviewed before. There are many scenes and as many viewpoint characters, but they all revolve around a central premise: a hundred years from now, freedom is ended, humanity is stagnant, and just one sliver of hope remains – a harsh world around the star e Eridani called Rustum.

I was not particularly charitable to Anderson when I first reviewed Robin Hood's Barn and The Burning Bridge, the two stories that comprise the first half of Orbit. He'd recently written the abysmal Bicycle built for Brew, and in general, he was at the tail end of a multi-year slump (and I had no way of knowing its end was near). Moreover, the stories did not do well on their own; giving them a common premise gave them a combined value greater than their sum.

So Anderson's stories are getting a second chance, just as the Earth gets a second chance, if only in the pages of Orbit Unlimited.

The first tale struck me much more favorably this time around. Robin Hood's Barn is the story of the choked, nearly hopeless Earth, and the old, canny politician, Svoboda, who tries to force one last gasp of colonizing desire by increasing the government's tyranny. The first time around, I took the story at face value, and it felt like yet another of those smug tales where one fellow has a preternatural ability to manipulate others such that the pieces always move as desired. Plus, there were no women in the story, and that always gets a strike from me unless there's a plausible reason. More on that later. On reexamination, it seemed Svoboda's gamble was far less certain, really an act of desperation that just barely paid off. That made it all much more palatable.

Now that I knew that Orbit's next story, The Burning Bridge, was set in the same universe, I was able to see it in a new light. I'd been lukewarm toward this story the first time. In Bridge, the colonial fleet in mid-flight when a message from Earth is received. Things are better, they are told, and they should come home. It's a tempting offer, one that Fleet Captain Joshua Coffin is sure the majority of the colonists will take. But he knows what they've fled, and he suspects that the respite will be a temporary one, perhaps already vanished after the decades it will take the fleet to return. So he forges a second message, one with more forceful language, one which could tip the vote in the direction he wants.

Again, this story is oddly anti-woman. The women colonists are kept segregated from the all-male astronauts even to the point of dressing in all-concealing clothing as the women do in some Moslem countries. That degree of conservatism seems counter to our current prevailing trends. Nevertheless, I found Bridge compelling.

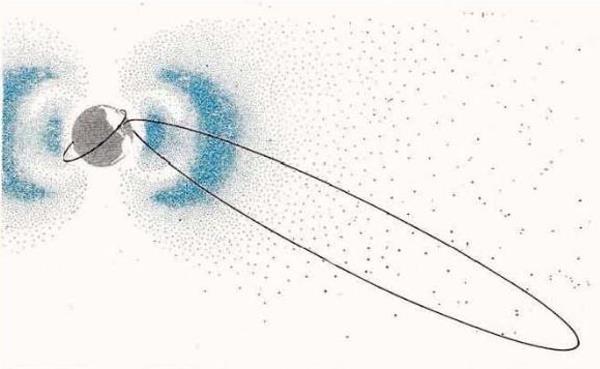

Part three, And yet so Far, came out in one of the last issues of Fantastic Universe back in October 1959. I didn't read it so I missed this story. In Far, the fleet has arrived at Rustum, but one of the vessels has suffered a catastrophe and now is adrift in the midst of planet's deadly Van Allen Belts. Sleeted with radiation, the ship is inaccessible and yet it must be accessed for it carries cargo vital to the colony's success. Admiral Nils Kivi refuses to consider a risky salvage mission for many reasons, not the least of which is his innate hostility for colonist Jan Svoboda, politician Svoboda's son. But Kivi has a soft spot for Svoboda's wife, Judith, and Jan is not above using her to manipulate Kivi into coming around. This is an impactful, bittersweet vignette. I can't imagine it being terribly successful without the context of the preceding tales, however. Moreover, it was published before Bridge, which must have confused hell out of anyone who read both stories.

The final and longest piece, The Mills of the Gods, has not, to my knowledge, appeared in any magazine. It is set ten years after planetfall. The three thousand colonists have vastly supplemented their numbers with children born in both the normal fashion and "exogenetically" – from frozen sperm and ova brought along to augment the colony's limited genetic range. There is an overt prejudice against the exogenes and a general oppressive conservatism to the colony in general. In cultural outlook, it feels like something out of the 19th Century (or perhaps the depths of the last decade). Men run business. Women tend house. It is as if the people of Rustum, in their escape from oppression, could think of no alternative to it. Rather like the Pilgrims seeking freedom from religious intolerance so that they could practice their own peculiar version in the New World.

At the start of Mills, one of the exogenes, Coffin's foster son, Danny, runs away from home. When he is not found on the relatively small mesa that forms the colony's borders, it is presumed that the youth descended toward sea level, into the thick atmosphere and alien ecology of Rustum's flatlands. Only Jan Svoboda is capable of helping Coffin make the trek to rescue Danny, and he must be bribed into it by the colony's wily mayor, Theron Wolfe.

This was my favorite of the book's episodes. Few writers can convey an alien world with both vividity and mundanity like Anderson. Their journey below the cloud deck into the noxiously dense atmosphere of Rustum was as exciting a travelogue as any Burroughsian tale of Pellucidar or Barsoom, but with the bonus of being scientifically rigorous. Of course, the emotional interplay between the religious Coffin and the cynical Svoboda formed the heart of the story, without which the scenery would have been pretty but pointless.

I'm not sure if Anderson had the entire novel in mind when he wrote the first words of Barn or if the concept evolved over time. There is such a consistency to the themes that I have to believe the skeleton was pre-plotted. Throughout, there are the recurring instances of what I'd term "selfless manipulation." The manipulator never relishes his actions, and it is only hoped that the results will be favorable. There is never an omniscient viewpoint from which we get the satisfaction that things will go as hoped (though the events of each succeeding story suggest that they did and will).

Orbit also repeatedly portrays humanity with an inclination toward the reactionary. Time and again, people must consciously choose to break free of the chains of conservatism, which is never depicted positively. In this context, the atavistic roles for women make more sense. Given that, both prior and subsequent to Anderson's bad period, the author portrayed women quite progressively, I have to think that the theme of sharp gender dichotomy was intentional – i.e. another facet of undesirable conservatism.

I could be entirely wrong, reading into Orbit what Anderson never intended. It could just be a happy accident that the four stories hang together so well. I doubt it, however; Anderson has proven to be a highly nuanced writer when he wants to be. Orbit has something to say, and it speaks with a clear voice throughout.

It's worth hearing it out. 3.75 stars.