by Mx. Kris Vyas-Myall

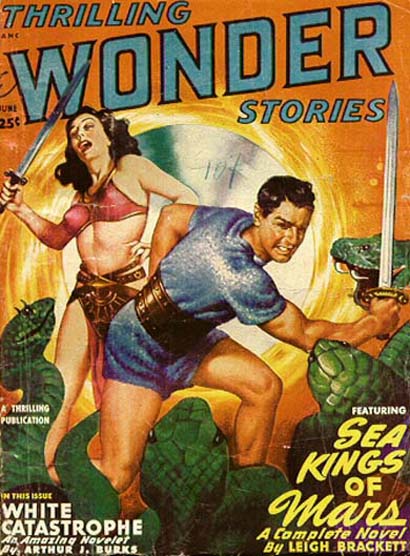

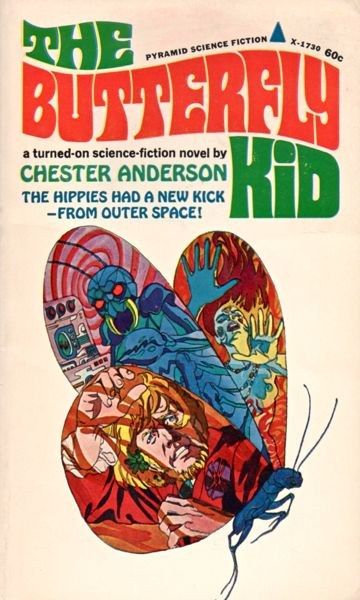

The Butterfly Kid by Chester Anderson

Drugs seem to be everywhere these days in science fiction. From Aldiss’ Acid War stories in New Worlds, through Dick’s Faith of Our Fathers in Dangerous Visions, to Brunner’s Productions of Time in Fantasy & Science Fiction. Some days I wonder if I am the only person in fandom that isn’t getting high and floating up among The Stars That Play with Laughing Sam’s Dice.

As such, it was only a matter of time before we got a real hip novel that fully blurs the boundary between fantastic and the psychedelic. Anderson is the one to give it to us.

One Pill Makes You Larger

So, what is this book about? On a basic plot level it is about Chester and Mike (fictionalised versions of the author and his sometimes co-writer) who seem to be sort of hippies living in 1977. They discover people affected by a mysterious new drug called Reality Pills, which cause psychedelic hallucinations to physically appear, such as a kid able to create butterflies and another person with their own halo. They set about tracking down the source of this, which, as the cover gives away, turns out to be extra-terrestrial.

As you can imagine, this gets very surreal quickly. Here is a sample conversation:

“Excuse me,” said another tall blue lobster, making its way to the john.

“One of yours?” I wondered. “I thought it was one yours.”

“I don’t like blue lobsters.”

Your willingness to just go with these kinds of sections without any prelude will likely dictate your enjoyment of the novel.

One Pill Makes You Small

But that, for me, isn’t what the book is really about. Rather, it gives us a window on to a subculture, the lives of dropouts and experimental rock groups in Greenwich Village right now. As I have not been there myself, I cannot speak to the reliability of Anderson’s vision but it is a vivid one imbued with a feeling of time and place, just as clear as if someone was talking to me about Middle Earth Club in London.

That is not to say I understood it all, and New Yorkers may well be able to “dig” more of it than I do, but it feels real and lived in, in a way so much science fiction does not.

And The Ones Your Mother Gives You, Don’t Do Anything At All

There are certain parts that do not work as well for me. It is filled with a lot of references to New York life and pop culture, some of which I understood (e.g. use of an obscure Tolkien simile) but other meanings were totally lost on me.

Perhaps more importantly, I am not certain if it is really “about” anything much. With its style and boundary pushing content, it is clearly aiming more for the literary than Campbell-esque end of the market. But Last Exit To Brooklyn this is not, whilst the current trial for that book’s UK publication hinges on its merits as a great work of literature, I cannot help but feel that argument could not be made in this case. Scenes like the Goddess Fellatia attempting to rape a police officer feel added more for the sake of shock value than any complex point being made.

Remember What The Dormouse Said, “Feed Your Head!”

Having said all that, I believe it still passes Sturgeon’s Law and is better than 90% of science fiction on the market. It is not perfect by any stretch and falls down in a number of areas. But it is still quite a groovy trip to take.

Four Stars

Here are some damning short takes from Kris and Jason–and both involve Lin Carter and Belmont Books!

The Thief of Thoth, by Lin Carter, and …And Others Shall Be Born, by Frank Belknap Long

"Belmont Double? Don't Bother. Dead Boring, Better-off Dreaming!"

Tower at the Edge of Time, by Lin Carter

"Ugh I just can’t get into this stupid barbarian book. Lin Carter’s writing is so full of stereotypes and clichés. I’ve tried a few times to get through it and can’t. I’m tagging out for this month."

by Gideon Marcus

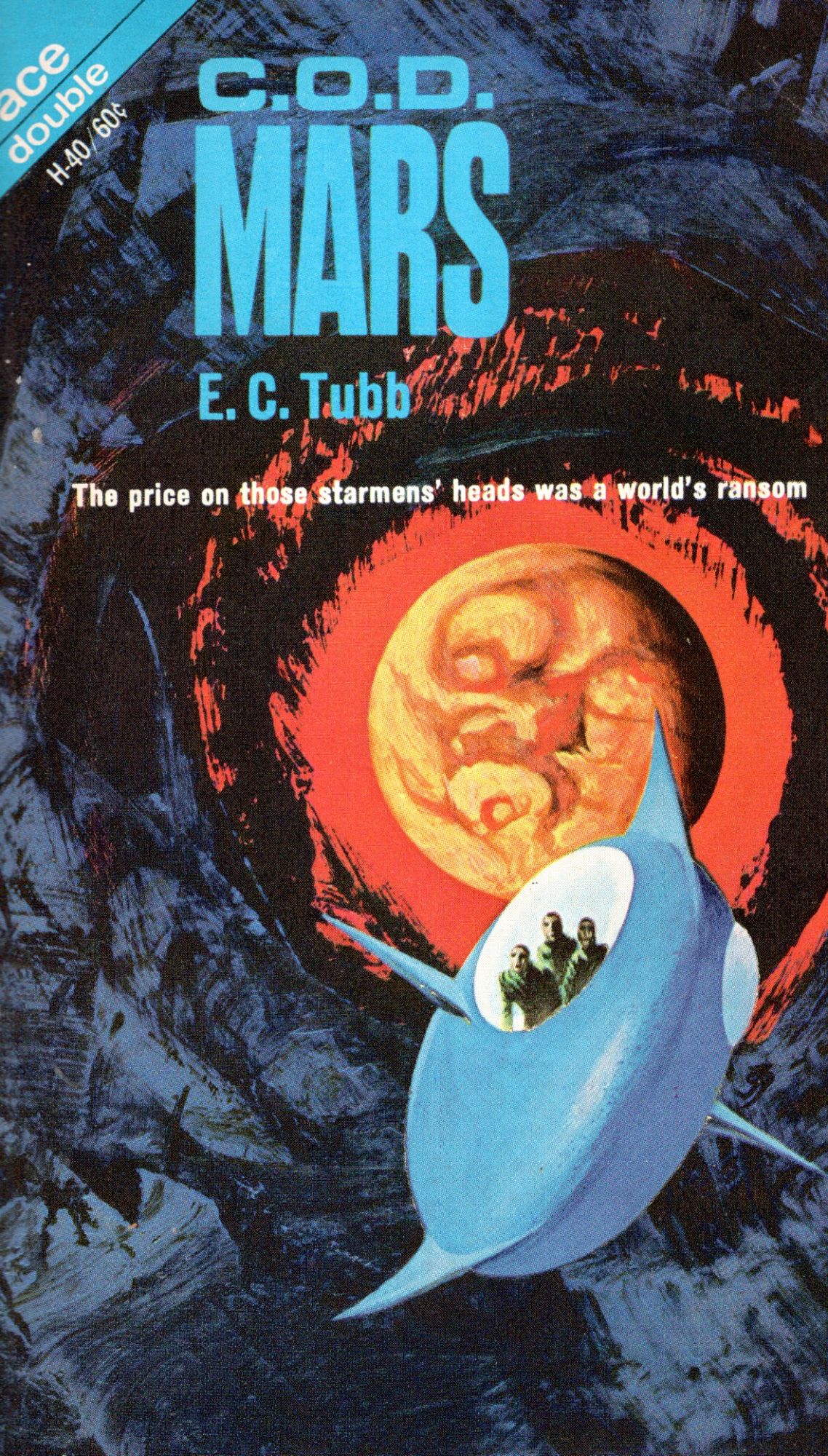

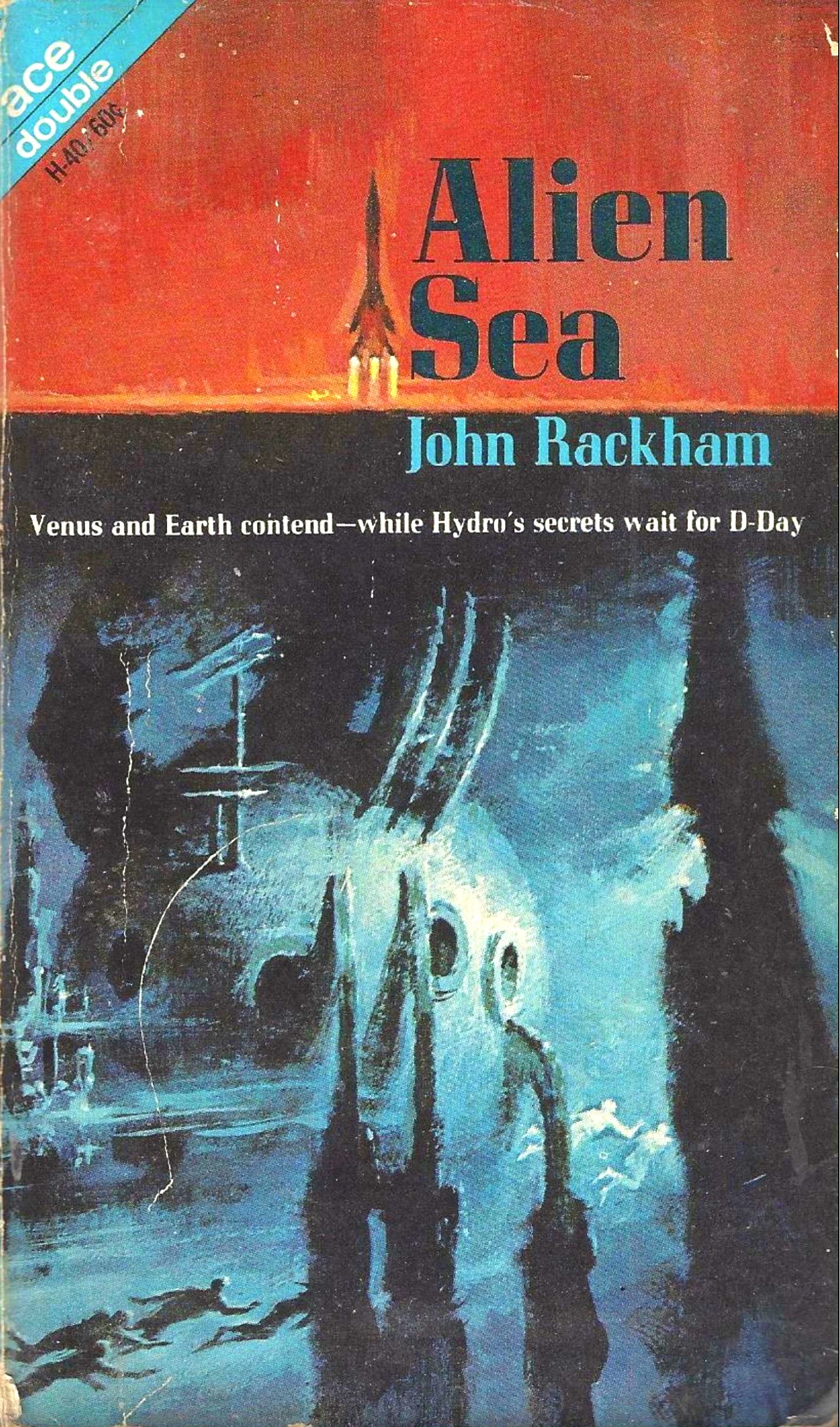

Ace Double H-40

Here's another shortish take, simply because this Double doesn't merit more:

C.O.D. Mars, by E. C. Tubb

Art by Jack Gaughan

The first interstellar journey results in horror: of the five crew, only three remain alive. The other two are carriers of an extraterrestrial disease, or perhaps worse–unwitting vessels of an alien invasion.

Someday, someone might write a superb book or series of books about a private investigator who jaunts through the asteroid belt, trying to thwart a Martian plot to weaponize alien technology (in the guise of infected humans) to gain an upper hand against Earth. This one isn't it.

It's not bad, but it's back to the humdrum potboiling that's associated with Tubb (sad, because we know he, and Ace, can do better–viz. The Winds of Gath). Part of the issue is the length; this is really a long novella, and the ending is rushed and pat–probably as a result.

Three and a half stars.

Alien Sea, by John Rackham

Art by George Zei

A ruined ship crewed by extra-terrestrials, the last survivor of a devastating planetary conflict, makes a close approach to their alien sun. As its hull chars and the crew and passengers succumb one by one to the heat, their only hope is that their cometary orbit will swing it quickly back for a rendezvous with their doomed world. But when they reach home, they find the doomsday weapons have sunk the two warring continents. All that is left is waves…and survivors on an enemy satellite. Together, they must build a new society, one free from strife.

Great premise! I was certainly hooked. Sadly, that's just the first chapter.

Then there's a jump of two millennia, and the focus is on a human conflict. Earthers have arrived on this alien world, unaware of the planet's history or inhabitants, intending to establish a fueling station. But rivals from Venus, peopled by intellectual exiles from Earth, have made contact with the indigenes. They are putting together an alien/Venusian invasion force to take Earth for their own.

The main body of the text, involving a telepathic sensitive who records experiences for television audiences at home, as well as the panoply of beautiful and topless (but at least capable) women he encounters, reads like a tepid planetary adventure from the '50s, complete with two-page digressions to lovingly describe some new piece of technology.

Two and a half stars.

by Fiona Moore

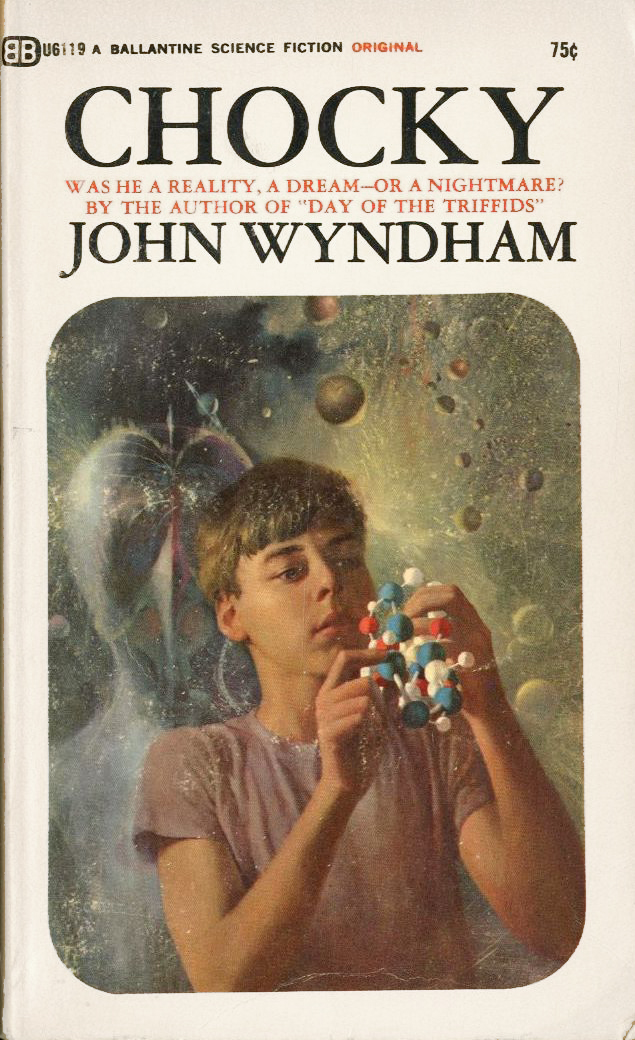

Chocky, by John Wyndham

John Wyndham’s latest novel, Chocky, an expansion of a novelette of the same name published in Amazing Stories in 1963, will be something of a disappointment to fans of the blend of cutting social commentary and dystopian science fiction which has characterised most of his novels to date. It’s much more in the mode of Wyndham’s earlier short fiction, but stretched out to the point where the conceit fails to hold the reader’s attention.

Plotwise, not an awful lot happens. A young boy, Matthew Gore, develops what his father, our point-of-view character, takes to be an imaginary friend, Chocky. It’s fairly apparent to the reader, though not so much to his family and teachers, that Chocky is an alien scout who is investigating the Earth through a telepathic rapport with Matthew. Chocky asks a lot of questions about things like geography, internal combustion engines, and gender; in return Chocky teaches Matthew sophisticated mathematical concepts like binary systems, and is sometimes able to take him over and impart abilities he doesn’t naturally possess. After a couple of incidents where Chocky, working through Matthew, does something which winds up in the national press, the family comes to wider, and possibly more sinister, attention.

And… well, that’s it. The action never gets exciting enough to be a thriller. Matthew and his family are never well-developed enough for this to become a poignant character piece. Details like the fact that Matthew is adopted are introduced but never achieve wider relevance. Matthew’s collection of busybody relatives lurk in the wings as a threat to Chocky’s privacy, but that’s all they remain: a minor complication. There’s very little sense of peril or threat from Chocky as there was from the children in The Midwich Cuckoos; the alien is just here to observe, not to take over. The setup, with a cosy suburban family, suggests that Chocky will upend that cosiness and force their prejudies and banalities into the open, but we’re disappointed on that score too. Wyndham does have some of his usual fun with the foibles of middle-class British society, but he never really twists the knife.

It’s frustrating because this could have been a much more exciting and relevant book. A story in which a little boy’s life is torn apart by scientists and politicians desperate to make first contact with aliens could have been heartrending; a story in which a lonely child’s isolation is used for sinister ends by a non-human being likewise. The first part of the book focuses so heavily on the social pressure Matthew’s parents felt to have children that one thinks this will be one of the themes of the story, however, this isn’t paid off either.

But there’s not much point in speculating about what Chocky could have been. It is what it is—an overextended novelette that promises much but delivers little, and is a disappointment compared to the works which made Wyndham famous. Two out of five stars.

![[February 14, 1968] Triple John (February 1968 Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/680214titles-672x372.jpg)

![[October 14, 1967] Threat level: High (October Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/671014covers-672x372.jpg)

![[July 18, 1967] Highs and Lows (July Galactoscope #2)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/670718covers-672x372.jpg)