by Kaye Dee

by Kaye DeeDespite the continued hiatus in human spaceflight on both sides of the Iron Curtin, March and early April have been a busy time in space exploration. But, sadly, I have to commence this review with the tragic news that Colonel Yuri Gagarin, the first person in space, was killed in a plane crash during a training flight on 27 March. Very little is currently known about the circumstances surrounding Gagarin’s death, which has occurred just one month shy of the first anniversary of the loss of Cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov in the Soyuz-1 accident.

Loss of a Space Hero

Loss of a Space HeroThere have long been rumours that the Soviet leadership refused to allow Gagarin to fly high performance jets or make another spaceflight due to his invaluable propaganda status as Cosmonaut No. 1. However, it seems that since Gagarin completed an engineering degree in February, he had finally been allowed to resume flight status and was undertaking training flights to regain his lapsed jet pilot qualifications.

According to an official government commission investigating the crash, Col. Gagarin was flying a two seat MiG-15 trainer with Colonel Vladimir Seryogin, 46, described as an experienced test pilot and instructor on the training flight. Taking off at 10 a.m., Gagarin and Seryogin apparently flew east 70 miles from Moscow. After completing the training flight, around 10.30, Gagarin radioed that he was returning to base. The plane was then at 13,000 feet. A minute later ground control could not establish contact.

A MiG-15UTI, the same type as the aircraft Gagarin was flying at the time of the crash

A MiG-15UTI, the same type as the aircraft Gagarin was flying at the time of the crashAn air search began, and a helicopter found the wreckage in a forest. The plane had dived into the ground at an angle of 65 to 70 degrees and was destroyed, killing both men. No information as to the cause of the crash has so far been forthcoming, but a story has been circulated that Gagarin heroically sacrificed himself, refusing to bail out of his stricken aircraft to guide it away from crashing in a populated area. How much truth there is to this, or whether it is pure propaganda, cannot be determined at this time.

Cosmonaut No. 1 is “flying through space forever”

Following an autopsy, the bodies of Gagarin and Seryogin were cremated the day after the crash and the ashes returned to Moscow, where the urns lay in state for 19 hours in the Red Banner Hall of the Soviet Army. Thousands are reported to have filed past to pay their respects to the world’s first space traveller. Thousands more lined the streets as the flower-covered urns, borne on a caisson drawn by an armoured troop carrier, moved slowly to Red Square along a 2½-mile route. The funeral procession included the Gagarin and Seryogin families and the highest leaders of the Soviet state and Communist Party.

The funeral procession for Gagarin and Seryogin making its way towards Red Square

The funeral procession for Gagarin and Seryogin making its way towards Red SquareGagarin and Seryogin were both interred in the Kremlin Wall, behind Lenin's Tomb in Red Square. In what is said to be a rare honour, car horns, factory whistles and church bells sounded in unison as the urn bearing Gagarin's ashes was inserted into a niche in the red brick wall. Then the nation fell still for a minute of silence, followed by a final salvo of cannon fire. A day of national mourning was also declared, the first time this has ever been done in the USSR for someone not a national leader. President Johnson, UN Secretary General U Thant and other world leaders sent messages of condolence. John Glenn sent a personal letter of sympathy to Col. Gagarin’s wife Valentina.

Seryogin and Gagarin buried side by side in the Kremlin Wall. Their various honours and awards are displayed before their portraits

Seryogin and Gagarin buried side by side in the Kremlin Wall. Their various honours and awards are displayed before their portraitsGagarin was just 34 years old when he died, leaving two young daughters, aged nine and seven. He was based at the cosmonaut training centre near Moscow, involved in training other cosmonauts when not engaged in official duties as a public figure. Little is known about Col. Seryogin, but he has been described as a Hero of Soviet Union and the commander of an air unit. It is unknown if he is also a member of the Soviet cosmonaut corps or has any other role in the Russian space programme.

Gagarin’s words upon landing after his space flight were “I could have gone on flying through space forever”. Though he never returned to space in this life, his spirit surely resides in the cosmos now.

Making up Lost Ground?

The somewhat mysterious Zond-4 unmanned spacecraft was launched on 2 March. A TASS news agency announcement of the launch described Zond-4 as an “automatic station”, “designed to study the outlying regions of near-earth space.”

Thanks to my friends at the Weapons Research Establishment, here is a photo of a Proton rocket, rumoured to be the type used to launch Zond-4.

Thanks to my friends at the Weapons Research Establishment, here is a photo of a Proton rocket, rumoured to be the type used to launch Zond-4. TASS reported that Zond-4 was put into an initial 170-mile parking orbit, before being sent on a “planned flight” further into space, apparently reaching the environs of the Moon. According to my contacts at the WRE, Zond 4’s flightpath reached an apogee of 240,000 miles, “comparable to lunar altitude”.

No further information was released by TASS about the mission, which has occurred several years after previous launches in the Zond series: Zond-1 was launched in April 1964, Zond-2 in November that year, and Zond-3 in July 1965. “Zond” is the Russian word for “probe” and these earlier spacecraft were apparently planetary or lunar missions. Could Zond-4 actually have been an attempt by the Soviet Union to make up lost ground with a test of the new Soyuz spacecraft, presumably redesigned or modified following the failed Soyuz-1 mission last year?

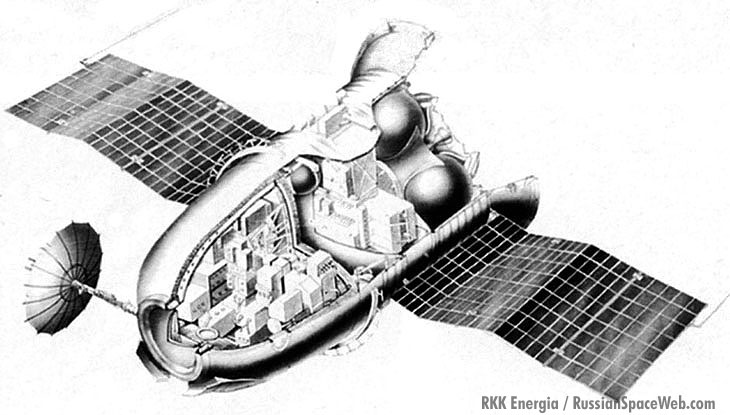

Does this cutaway illustration represent mysterious Zond-4? My WRE friends think it might!

Does this cutaway illustration represent mysterious Zond-4? My WRE friends think it might!It would hardly be the first time that the Soviet Union has concealed real purpose of a space mission behind the name of a different spacecraft series. (paging Mr. Kosmos/Cosmos!). As the Soyuz vehicle is believed to be the USSR’s answer to Apollo, a test of an improved spacecraft out to lunar distance would certainly make sense at this time, with the Apollo 6 mission (see below) testing out the Apollo Command and Service Modules just a few days ago.

Whatever its mission, Zond-4 returned to Earth on 9 March, but there was no official communique on the conclusion of the flight. This silence suggests that the re-entry failed in some way and that the spacecraft was either destroyed on re-entry or crashed on landing. If Zond-4 was a test of the Soyuz vehicle, could its loss have been due to a repeat of the parachute failure that doomed Soyuz-1 last year? If this was the case, it does not bode well for the USSR getting its lunar programme back on track in time to challenge the United States in the race for the Moon.

Go, OGO-5!

Just two days after the launch of Zond-4, the United States launched the latest satellite in its Orbiting Geophysical Observatory (OGO) series of scientific satellites. OGO-5 soared aloft on 4 March, establishing itself in a highly elliptical orbit with a 170 mile perigee and a 92,105 mile apogee. The orbital inclination was 31.1 degrees, with the satellite taking 3796 minutes to complete one orbit. The 1,347 lb satellite carries more experiments than any other automated spacecraft to date.

OGO-5 First day Cover and informational insert, courtesy of my Uncle Ernie, the philatelic collector

OGO-5 First day Cover and informational insert, courtesy of my Uncle Ernie, the philatelic collectorOGO-5 is primarily devoted to observation of the Earth’s upper atmosphere and its interaction with conditions in the space environment. Like earlier OGO satellites, it carries instruments for studying solar flares (which can also detect cosmic X-ray bursts) and a gamma-ray detector. This will enable it to examine the hazards and mysteries of Earth's space environment at a time when radiation-producing flares on the Sun are intensifying. It will also chart magnetic and electric forces in space, measure gases in Earth's upper atmosphere, investigate the Aurora Borealis over the North Pole and listen for the puzzling radio noises that have been detected from the planet Jupiter. Each of OGO-5’s predecessors is still operational at this time, so let’s hope the latest Orbiting Geophysical Observatory also has a long life ahead of it.

Apollo 6: NASA Keeps Moving Forward

If Zond-4 has been an un-announced trial of the USSR’s Soyuz lunar spacecraft, Apollo-6 has been NASA’s very public test flight of the Saturn-5 rocket and some of the modifications to the Apollo Command Module.

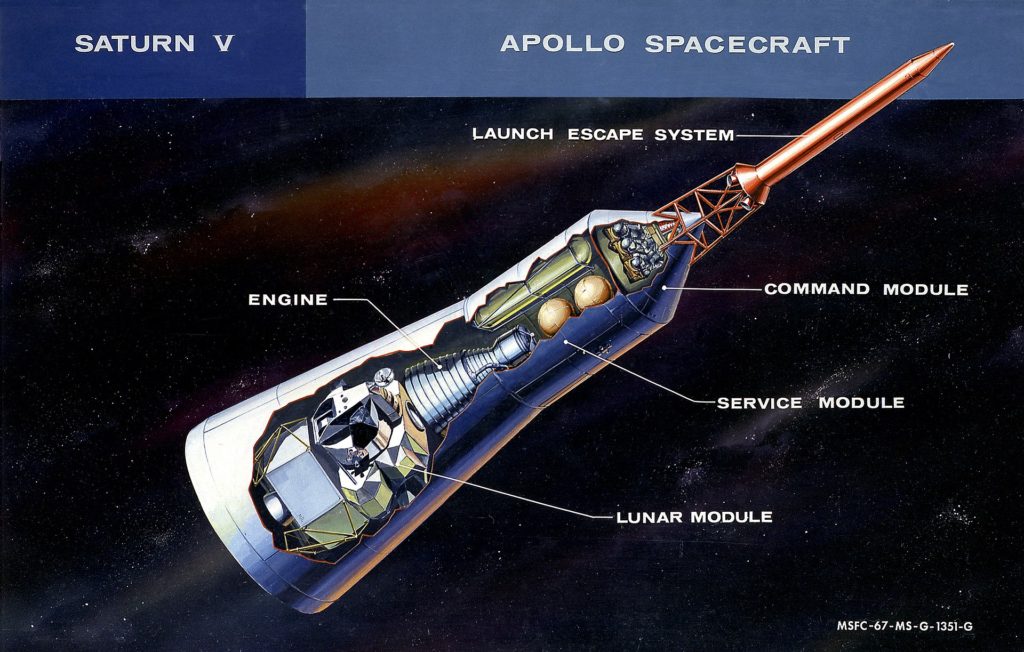

Launched on 4 April, Apollo-6 marked the second test flight of the massive Saturn-5 launch vehicle, crucial for reaching Moon. The primary objective of the mission was to test the performance of the Saturn-5 and the Apollo spacecraft, the first time that the Command and Service Modules (CSM) would be fully tested in space. In particular, the mission was intended to demonstrate that the Saturn-5’s S-IVB third stage could send the entire Apollo spacecraft (CSM and Lunar Module) out to lunar distances. Although things didn’t go quite to plan, Apollo-6 did accomplish its basic objectives.

Launched on 4 April, Apollo-6 marked the second test flight of the massive Saturn-5 launch vehicle, crucial for reaching Moon. The primary objective of the mission was to test the performance of the Saturn-5 and the Apollo spacecraft, the first time that the Command and Service Modules (CSM) would be fully tested in space. In particular, the mission was intended to demonstrate that the Saturn-5’s S-IVB third stage could send the entire Apollo spacecraft (CSM and Lunar Module) out to lunar distances. Although things didn’t go quite to plan, Apollo-6 did accomplish its basic objectives. An All-Up Test Flight

The Apollo 6 launch vehicle was the second flight-capable Saturn-5, AS-502, its simulated payload equal to about 80% of a full Apollo lunar spacecraft. The CSM it carried was a Block I (Earth-orbit mission) type, with some Block II (lunar mission) modifications. According to NASA “more than 140 tests since last October showed modifications of the Apollo spacecraft since the 1967 disaster had drastically reduced the hazard to life”.

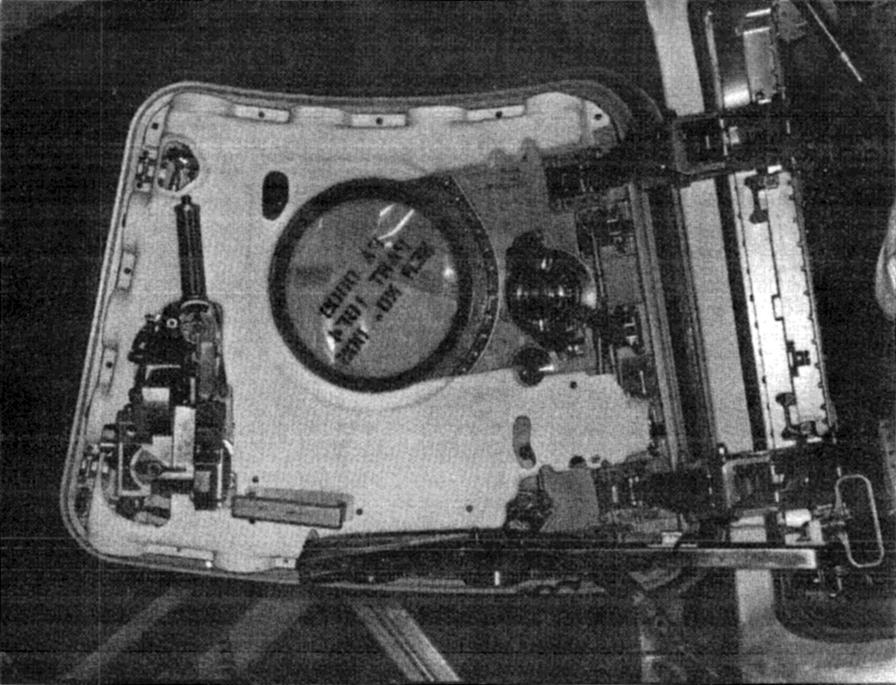

Possibly the most important modification was a new crew hatch, intended to be tested under lunar return conditions. This new hatch incorporated the heat shield and crew compartment hatches of the original Apollo design into a single hatch, called the "unified" design. This has been in response to the Apollo-1 investigation board finding that the dual hatches were too difficult to open in case of emergency and had contributed to the deaths of the crew.

Apollo-6's redesigned unified hatch, photographed during a post-flight inspection of the Commend Module

Apollo-6's redesigned unified hatch, photographed during a post-flight inspection of the Commend ModuleLike the earlier Apollo-5 test flight, Apollo-6 carried a simulated Lunar Module (LM) which lacked the descent-stage landing gear. It also had no flight systems, and its fuel and oxidiser tanks were liquid-ballasted. While the LM remained inside the Spacecraft-Lunar Module Adapter throughout the flight, its ascent stage was instrumented to determine the craft’s structural integrity and the vibration and acoustic stresses to which it was subjected.

Apollo-6's "legless Lunar Module", formally called the Lunar Test Article LTA-2R

Apollo-6's "legless Lunar Module", formally called the Lunar Test Article LTA-2RA few weeks prior to launch, NASA announced that, to further reduce fire hazards that contributed to the deaths of Apollo-1 astronauts, it intended to change to a mixture of 60% oxygen and 40% cent nitrogen in the Command Module, while the spacecraft and its crew are on the ground and during launch. Once their spacecraft left the launch pad, the astronauts would switch to pure oxygen. Since the gas mixture will be used in the spacecraft only during ground operations, NASA has not planned any change in the existing environmental control system, so the decision did not affect the Apollo 6 mission.

Apollo 6: What Was Planned

The original Apollo 6 mission plan intended to send the CSM and simulated lunar module into a trans-lunar trajectory. (That trajectory, although passing beyond lunar orbit distance, would not encounter the Moon, which was in another part of its orbit at the time.) The Saturn-5’s S-IVB third stage would be fired for trans-lunar injection, with the CSM separating from the S-IVB soon after. The Service Module engine would then fire to slow the CSM, reducing its apogee to 11,989 nmi.

NASA illustration showing the CSM and LM inside the Spacecraft-Lunar Module Adapter, as they would be at trans-lunar injection

NASA illustration showing the CSM and LM inside the Spacecraft-Lunar Module Adapter, as they would be at trans-lunar injectionThe CSM would then return to Earth as if it had experienced “direct-return” abort during a Moon mission. As it returned, the SM engine would fire again, accelerating the CSM to simulate the conditions that an Apollo spacecraft would encounter on its return from the Moon: a re-entry angle of −6.5 degrees and velocity of 36,500 ft/s. The entire test flight was planned with a duration of about 10 hours.

Not Quite Going to Plan

After the launch was delayed for some days due to problems with guidance system equipment and fuelling, Apollo 6 made a smooth lift-off from Kennedy Space Centre. However, during the last ten seconds of first stage firing, the vehicle severely experienced a type of longitudinal oscillation known as “pogo”. Pogo occurs when a partial vacuum in a rocket’s fuel and oxidiser feed lines reaches the engine firing chamber, causing the engine to “skip”. The pogo phenomenon is well-known, since rockets have experienced it since the early days of spaceflight, and it occurred in launchers such as Thor and Titan II (used for the Gemini program).

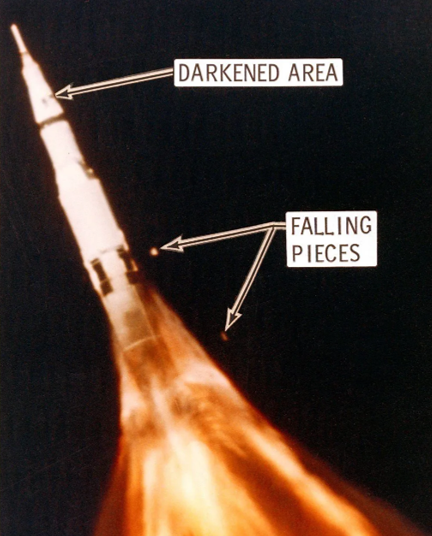

While the Apollo-4 Saturn-5 also experienced a mild form of pogo, Apollo-6 was subjected to extreme pogo vibrations. It appears that these oscillations, travelling along the length of the huge Moon rocket, caused multiple problems with the vehicle. Two engines in the second stage shut down early, although the vehicle's onboard guidance system was able to compensate by burning the remaining three engines for 58 seconds longer than planned. The S-IVB engine also experienced a slight performance loss and had to burn for 29 seconds longer than usual. Intense vibrations were felt in the Command Module that could have caused injuries had a crew been onboard. There was also some superficial structural damage to the Spacecraft Lunar Module Adaptor (SLA).

A chase plane image of the Apollo-6 launch, taken at approximately the time of the pogo oscillations. It shows an area of discoloration on the SLA indicative of superficial damage and what appears to be falling pieces of debris, perhaps a panel or two shaken lose by the pogo vibrations

A chase plane image of the Apollo-6 launch, taken at approximately the time of the pogo oscillations. It shows an area of discoloration on the SLA indicative of superficial damage and what appears to be falling pieces of debris, perhaps a panel or two shaken lose by the pogo vibrationsThe underperformance of the apparently pogo-damaged engines resulted in the third stage being inserted into an elliptical parking orbit, rather than the planned 100 nmi circular orbit. Although Mission Control decided that this did not prevent the mission from continuing, when the vehicle was ready for trans-lunar injection, the apparently damaged S-IVB engine failed to restart.

Repeating Apollo-4

Without the ability to continue with the original flight plan, Mission Control decided to complete some of the mission objectives by adopting a flight plan similar to that of Apollo-4. The SM's Service Propulsion System (SPS) was used to raise the spacecraft into an orbit with a 11,989 nmi apogee, from which it would re-enter. However, the SPS engine did not have enough fuel for a second burn to accelerate the atmospheric re-entry and the spacecraft was only able to enter the atmosphere with a velocity of 33,000 ft/s, instead of the planned 36,500 ft/s that would simulate a lunar return.

With the SM was jettisoned just before atmospheric re-entry, the CM splashed down 43 nmi from the planned landing site north of Hawaii, ten hours after launch. It was recovered by the USS Okinawa.

A Rocket's Eye View

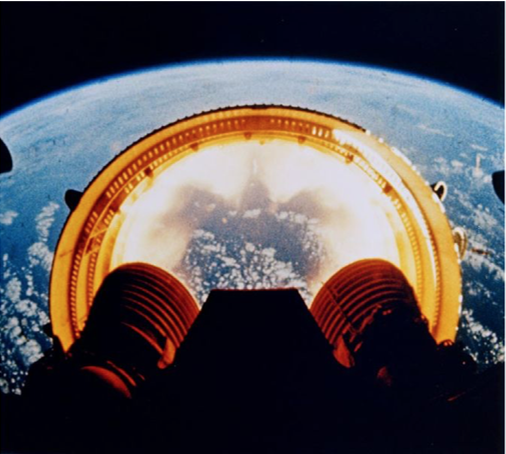

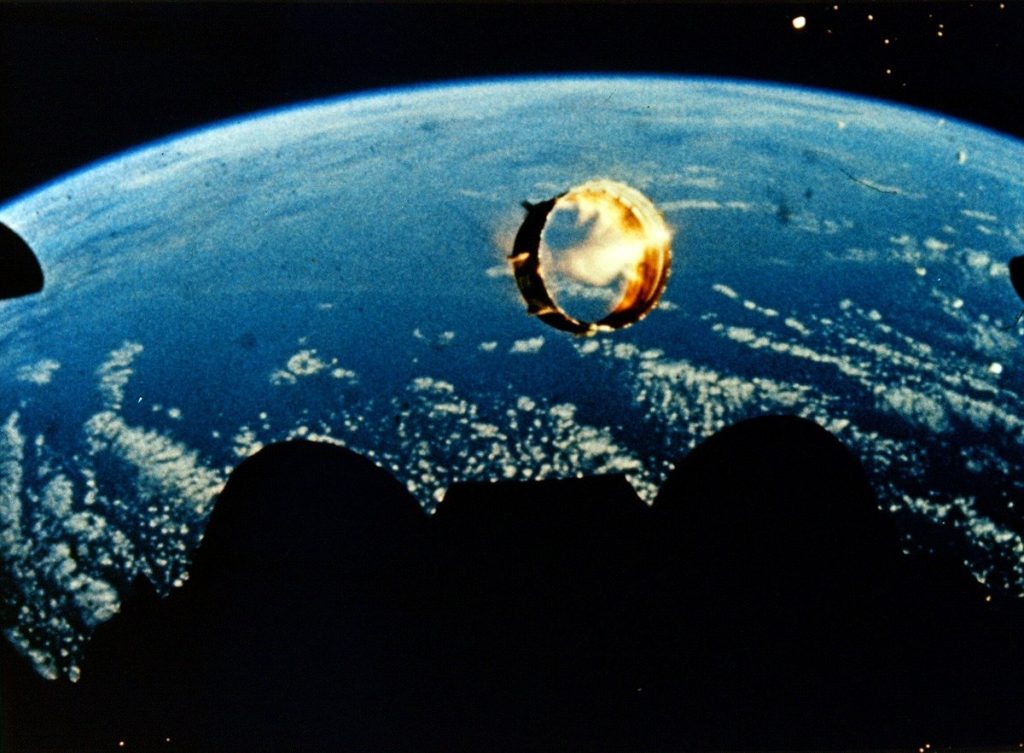

Unlike earlier unmanned missions, the Apollo-6 Saturn-5 was fitted with several cameras intended to be ejected and later recovered. Three of the four cameras on the first stage failed to eject and were lost and only one of the two cameras on the second stage was recovered. Fortunately, this camera provided spectacular views of the separation of the first and second stages.

Two spectacular views of the interstage between the first and second stages falling away, taken from Apollo-6's second stage camera. How amazing that we can now see events happening during a launch that cannot be observed from the ground!

Two spectacular views of the interstage between the first and second stages falling away, taken from Apollo-6's second stage camera. How amazing that we can now see events happening during a launch that cannot be observed from the ground!The CM also carried two cameras: a motion picture camera, intended to be activated during launch and re-entry and a 70mm still camera. Unfortunately, as the technical issues meant that the mission took about ten minutes longer than planned, the re-entry events were not filmed. However, the still camera, pointed at the Earth through the hatch window provided impressive photos of parts of the United States, the Atlantic Ocean, Africa, and the western Pacific Ocean. Advanced film and filters, improved colour balance and higher resolution have provided images that are a significant improvement on the photographs taken on previous American crewed missions and demonstrated that future imagery from space will be useful for cartographic, topographic, and geographic studies.

A view of the Dallas-Fort Worth area in Texas, taken from the Command Module's 70mm still camera. Special thanks to the Australian NASA representative for providing me with rush copies of these incredible Apollo-6 images for this article

A view of the Dallas-Fort Worth area in Texas, taken from the Command Module's 70mm still camera. Special thanks to the Australian NASA representative for providing me with rush copies of these incredible Apollo-6 images for this articleWhat’s Next for Apollo?

NASA announced in mid-March that its first Earth-orbiting Apollo mission will be launched on a Saturn 1 vehicle and spend as long as ten days in orbit. The flight, which could come as early as mid-August, will be crewed by astronauts Walter Schirra, Donn Eisele and Walter Cunningham. If that mission goes well and the Saturn-5 is cleared for manned launchings, astronauts James McDivitt, David Scott and Russell Schweickart will ride a Saturn-5 into Earth orbit two or three months later to conduct flight test of the lunar module.

Following the return of Apollo-6, Apollo Programme Director Samuel C. Phillips said, “there's no question that it's less than a perfect mission”, although the Saturn-5’s demonstration of its ability to reach orbit despite the loss of two engines, was “a major unplanned accomplishment”. However, Marshall Space Flight Centre Director Wernher von Braun has recognised that the “flight clearly left a lot to be desired. … We just cannot go to the Moon [with this problem],” referring to the extreme pogo experienced on the flight. This means that solving the pogo phenomenon is now a major priority for NASA in order to keep the Apollo program on track and bolster confidence in the Saturn-5 vehicle. Can they do it?

![[April 8, 1968] Ups, Downs and Tragedy: An Eventful Month in Space (Gagarin's crash, Zond-4, OGO-5, Apollo-6)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/680408gagarin-672x372.jpg)

![[January 24, 1968] On Track for the Moon (Apollo 5 and Surveyor 7]](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/apollo_5_patch-672x372.jpg)