Here's a couple of interesting space news items:

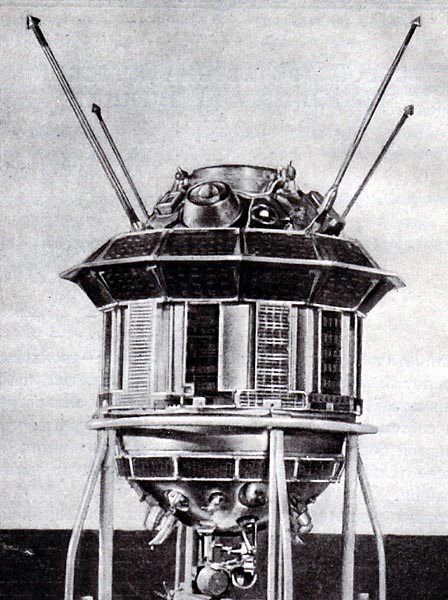

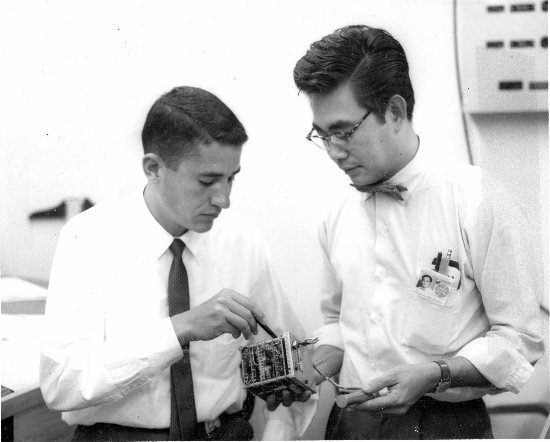

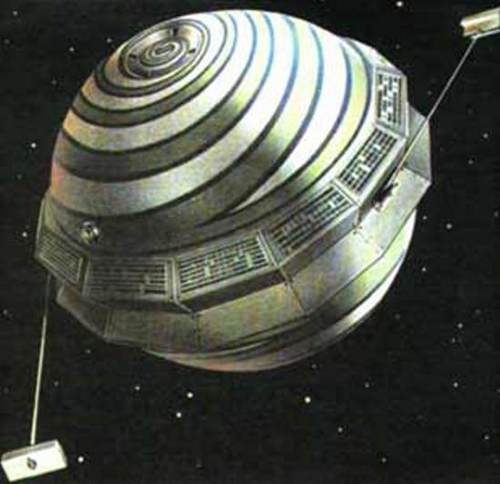

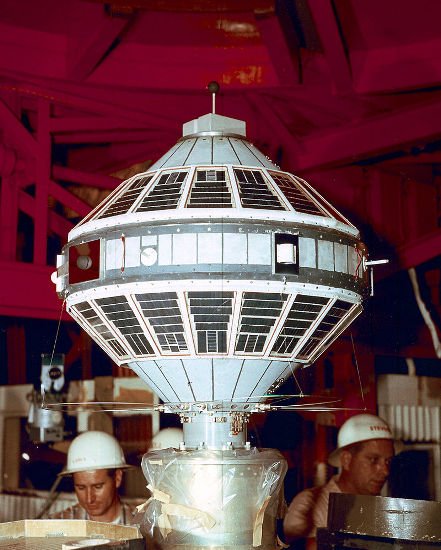

Firstly, a new Explorer (#7) has soared into the sky. This one was launched at the tip of a Juno II rocket, the kind that sent Pioneer 4 past the Moon and into solar orbit. Whereas Explorer 6 was known as "The Windmill," the quite different Explorer 7 has been nicknamed "The Gyroscope." Though the craft bears the same Explorer designation as its predecessor, it was actually made by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratories, the (somehwhat) friendly rival of Space Technology Laboratories, darling of the U.S. Air Force.

Explorer 7 is a lovely, complex satellite, with a battery of scientific instrumentation. Not only will it probe the radiation and micrometeoric environment of space, as prior spacecraft have done, it also wields a new experiment designed to measure the heat budget of the Earth. Simply, it will help determine how much of the sun's energy is absorbed and reflected by our planet, measuring quantitatively the sun's effect on the Earth. Pretty neat stuff! I will definitely report on the science as it is published.

Secondly, Explorer 6 has finally gone silent, but even mute, it has proven useful. On October 13, the Air Force shot a plane-launched Bold Orion anti-missile rocket at it to test our ability to intercept Soviet missiles in flight. I can't get exact figures, but it got pretty close, apparently. Probably close enough that, if the rocket had a little nuclear bomb on it, it could destroy an enemy missile.

Meanwhile, in the "why bother" department, a piece in the Miami News caught my attention. The first, titled Space Science Called Foolish, has Brown University Professor Emeritus Dr. Charles A. Krause humbugging all over the space program. "There's a lot of nonsense going on in the field of space science," the esteemed doctor opined. "I'm for forgetting this nonsense and keeping our earth science up to date." He went on to say, "Space is a vacuum, void of matter or gas. There is nothing to be gotten out of a vacuum. We can get a lot out of the Earth."

Apparently, Dr. Krause is not aware that the Earth's upper atmosphere and magnetic field, integral parts of this planet, can only be surveyed from space. Moreover, he is blissfully ignorant that there is plenty to be gotten from a vacuum, one far better than any that can be manufactured on Earth. In any event, the Sun, the Moon, the planets, the asteroids, meteors, comets, micrometeoroids, charged particles, solar wind, etc. all exist in space. It is hardly devoid of matter or gas. Understanding how they move and interact perfects our knowledge of Earth-bound physics.

In short, Dr. Krause is a schmuck. And so are the editors of the Miami News.

Oh, and here's another one: Rockets too Puny for Moon. It's less inflammatory, but it is already out of date. The seminal quote is, "U.S. guidance systems are on par with those of Russia. The weight-carrying capacity of our moon rockets is not." The unknown author's point is that, until we get beefier rockets, we can't send guidance good enough to get a probe on the moon.

Given that the new Atlas Able will be launching before the end of the year, this defeatism seems misplaced. I guess we'll see.

Footage from a new TV show, Destination Space

—

Note: I love comments (you can do so anonymously), and I always try to reply.

P.S. Galactic Journey is now a proud member of a constellation of interesting columns. While you're waiting for me to publish my next article, why not give one of them a read!

(Confused? Click here for an explanation as to what's really going on)

This entry was originally posted at Dreamwidth, where it has comments. Please comment here or there.