What makes a story worth reading?

As a writer, and as a reader who has plowed through thousands of stories over the past decade, I've developed a fair idea of what works and what doesn't. Some writers cast a spell on you from the first words and maintain that trance until the very end. Others have good ideas but break momentum with clunky prose. Some turn a phrase skillfully, but their plots don't hold interest.

I find that science fiction authors are more likely to hang their tales on plot to the exclusion of other factors. This is part of the reason our genre is much maligned by the literary crowd. On the other hand, the literary crowd tends to commit the opposite sin: glazing our eyes over with experimental, turgid passages.

A few authors have managed to bridge the gap: Theodore Sturgeon, Avram Davidson, Daniel Keyes. And, in general, I think the roster of science fiction authors, as they mature, are turning out better and better stuff.

Sadly, Astounding is rarely the place you'll find them.

After last month's decent issue, I had looked forward eagerly to this one, the July 1960 edition. It's not unmitigatedly horrible, but it does sink back into the level of quality I've come to expect from Campbell's magazine. Let's take a look:

Poul Anderson, with whom I've had a rocky relationship over the last decade, begins a new serial called The High Crusade. It's about a 14th century English town that gets attacked by an alien scout ship. Surprisingly, the "primitive" residents manage to overpower the alien crew and commandeer their ship, which they then sail across the suns to another alien outpost, where they defeat a contingent of the more technologically advanced aliens.

Now, this is the kind of story editor Campbell loves: plucky humans defeating inferior space aliens. I suspect that the humans in Crusade will face increasingly ridiculous odds, always coming out on top.

This should bother me. On the other hand, the story is really quite well written, with an excellent use of archaic language, a fair depiction of the age, and compelling characters. Moreover, I have the faintest suspicion that Anderson is satirizing Campbell's fetish, hence my prediction that the story will be ever more over-the-top.

Sadly, this incomplete tale is the high point of the book. Chris Anvil is up next with The Troublemaker. It starts out promisingly, involving an interstellar cargo ship and the seditious new cargo inspector who joins the crew. The fellow has a knack for dividing and conquering, causing friendships to disintegrate and morale to plummet. But the Captain's solution for the problem comes out of nowhere and is thus unsatisfying. Which brings me back to my preface. Writer tip #1: Foreshadowing is important. No one likes a mystery novel where the murderer is not presented before the detective explains whodunnit. A good writer introduces concepts earlier in the story if they are to be used later.

Onto the next story. Its author, Dean McLaughlin, has been writing for various digests over the past decade. I know I've read a few of his stories, but they do not stand out in my memory. In any event, his The Brotherhood of Keepers leaves much to be desired. In this case, characterization is utterly subverted to an involved, somewhat odious plot. There is a race of near-sapient upright seals on a harsh alien world. They are on the brink of becoming sentient, and a human outpost has been established on their planet, despite the uncomfortable conditions, to watch the transition. There are three main characters, all made of the same grade of carboard.

You have the fatuous, bleeding heart animal rights activist who wants to bring an end to the suffering of the "floppers," both at the hands of their environment and the scientists (who employ them as slaves and vivisect them every so often). You have the xenophobic scientist who pushes all of the activist's buttons in the hopes that this will bring about a relief mission, allowing the floppers to be "saved" before they become truly sentient. Finally, you've got the outpost chief. He grieves for the cruel plight of the floppers, but he feels it would be more cruel to deny them their destiny of intelligence.

On the face of it, this could have been a very interesting story. Aside from the truly hackneyed portrayal of the characters, I took umbrage with the way the floppers were treated by the humans. Granted, the most egregious comments made by the scientist character ("they're only animals," he says of creatures smarter than chimpanzees) were probably designed specifically to goad the activist, but they must reflect, at least in part, the deeply held sentiments of his fellow researchers. As any sociologist would tell you, the best way to study a society probably does not involve murdering its members.

Asimov has a fair sequel to his article on animal phyla, published month before last. This one is called, appropriately enough, Beyond the Phyla. The good doctor makes some interesting speculation on the next evolutionary steps humanity might take. They will not involve physical adaptations, he opines, but rather a level of social cohesion that will transform our race into a larger, integrated whole.

It's a pity that Isaac doesn't write fiction anymore; I imagine folks will be lifting his non-fiction ideas and turning them into stories soon.

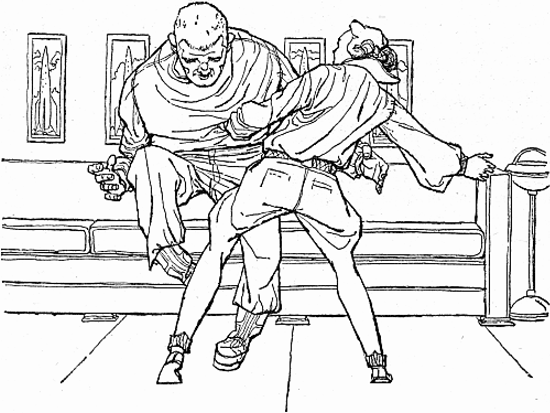

Finally, we have Subspace Survivors, by the renowned Doc Smith, himself. All due respect to an admitted titan of the field, this is not a very good story. It's something of a relic from the pulp era, this tale of nine survivors on a wrecked interstellar vessel, four of whom are psionically gifted (of course). Writer tip #2: Description should be incorporated seamlessly into a narrative, not obtrusively inserted in-between bits of action.

There are two women in this story. They acquit themselves rather well against two of the castaways, who turn out to be bad men, but for the most part, they are content to be submissive child incubators, comforted in times of distress by their lantern-jawed officer husbands. Feh.

I recently exchanged letters with a fan who expressed his dislike for magazines with only a few, longer stories. I told him that I didn't mind them so long as the stories were good. But, I am starting to take his point.

See you shortly with more fiction reviews!