by Gideon Marcus

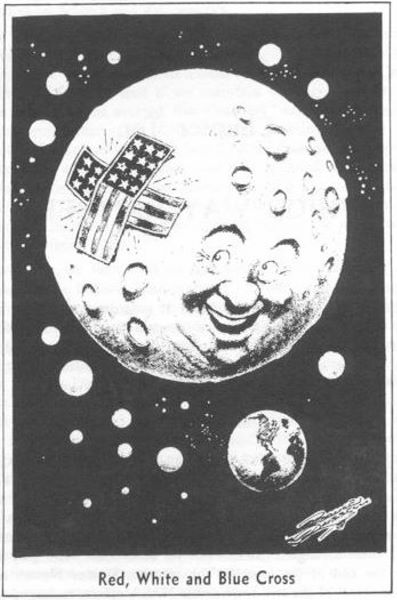

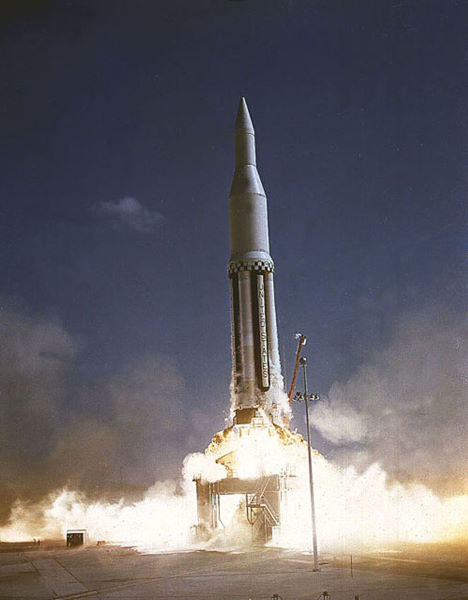

A wise fellow once opined that the problem with a one-dimensional rating system (in my case, 1-5 Galactic Stars) is that there is little differentiating the flawed jewel from the moderately amusing. That had not really been an issue for me until this month's issue of Analog. With the exception of the opening story, which though it provides excellent subject matter for the cover's striking picture, is a pretty unimpressive piece, the rest of the tales have much to recommend them. They just aren't quite brilliant for one reason or another.

So you're about to encounter a bunch of titles that got three-star ratings, but don't let that deter you if the summaries pique your interest:

The Weather Man, by Theodore L. Thomas

"Everybody complains about the weather, but nobody does anything about it," so the old saw goes. But in Thomas' future, the Earth's weather is completely under the control of the all-powerful Weather Bureau; and it follows that the associated Weather Council is ruler of the world. One councilor decides to stake his political future on the odd request of a resident of Holtville, California whose dying wish is to see snow before he dies…in July.

A couple of notable points: We seem increasingly confident that weather will be a trivial problem to solve. That's reassuring given the threat of global warming. Another is the featuring of Holtville, a tiny farm town in the middle of the country's richest farmland: the Imperial Valley. I know the place fairly well – it's the next town over from my hometown of El Centro, the county seat. Aside from its healthy Future Farmers of America chapter, its surprisingly able High School Speech Team, and that it was the residence of a brief ex-girlfriend, it has no outstanding qualities. Just another stinky, buggy, windy settlement in an irrigated hot desert.

Anyway, Weatherman is a dull, plodding piece, and in contrast to the later stories in this issue, has very few trappings of a far, or even near, future. Aside from the boats that sail over the sun, that is. I'm not sure how pinpoint weather modification is somehow easier by tampering with a star rather than its planet. I couldn't swallow it. Two stars.

Three-Part Puzzle, by Gordon R. Dickson

In galaxy where the races divide neatly into Conquerers, Submissives, and Invulnerables (the last uninterested in conquering and incapable of beating into submission), what do you do when you discover humanity fits into none of these categories? A cute tale no longer than it needs to be. Three stars.

Anything You Can Do! (Part 2 of 2), by Randall Garrett

This latter installment depicting the battle of superhuman Stanton brothers vs. the frighteningly alien Nipe (begun last month) ends satisfactorily. In fact, Garrett weaves together a number of plot threads with some fair skill, explaining the weird psychology of the shipwrecked ET; resolving the mysterious situation of the twin Stantons, one of whom had been crippled from birth and yet no longer has any physical ailments; and concluding the Nipe menace without resorting to bloodshed. I am shocked, myself, to admit that I liked a Garrett story from start to finish, without qualifications. Could the Randy fellow have turned a corner? Three stars for this part, three-and-a-half in aggregate.

Interstellar Passenger Capsule, by Ralph A. Hall, M.D.

Dr. Hall takes on the currently popular topic of panspermia, the idea that life is spread around the cosmos by interstellar meteors. It's overlong, a bit meandery, and I don't believe for a second that meteorites have been found with spores in them (at least, spores that were there before their carrier hit the Earth). It reads like something submitted for a high school paper. In that context, it might get a 'B.' Here, it barely rates two stars.

The Sound of Silence, by Barbara Constant

An interesting, almost F&SFish piece about a young mind-reader who struggles to come to grips with her powers. Lonely is the existence of a telepath with no one to send thoughts to. I've never heard of Ms. Constant, but this was a solid piece, and a somewhat unique take on a hoary topic. Three stars.

Novice, by James H. Schmitz

Young Telzey Amberdon has got quite a task ahead of her! Can this second-year law student prove the sentience of an extraterrestrial race of giant cats while thwarting the nefarious schemes, upon Telzey and the kitties, of her evil aunt? Here's an interesting story that combines telepathy, a female protagonist, and felines. We also see progressive details like a Galactic Federation Councilwoman and a wallet-sized law library. Its demerits are a slightly disjointed narrative style and a coda that is a bit creepy in its implications. Nevertheless, I'd love more in this vein, please. Three stars.

***

That tallies up to an average of 2.7 – not very promising on the surface, but if you take out the leading novelette and the lackluster science fact article, you're left with some very readable, if not astonishing, stuff. I'm not sorry I read this ish, which is more than I can say for some of the prior ones.