by Gideon Marcus

[We've just updated KGJ for the Fall. Check out our line-up of new hits!]

Life is a series of cycles: The seasons change; people are born, have children, die, and their children do the same; the government takes its pound of flesh every April. And every month, I slog through an increasingly tall pile of science fiction books. Like the Hydra of Greek legend, any conquest I make is fleeting, for there is always a new set to review.

Of course, my labor is not generally an unpleasant one. When I get my hands on an exciting new book or a magazine dense with worthy selections, life is grand. On the other hand, when the reading gets difficult, that's its own kind of hell, particularly when the reading involves magazines. I can drop an unpromising book without much twinging of conscience, but I am committed to reviewing every issue of every American SFF magazine. That can be rough.

To wit, the October 1963 Analog is a tedious slog. While I give many of the individual pieces passable "3-star" ratings, most barely cross that threshold of acceptability, and taken together, they make a kind of mind-numbing sludge. Aren't you glad I read this issue for you?

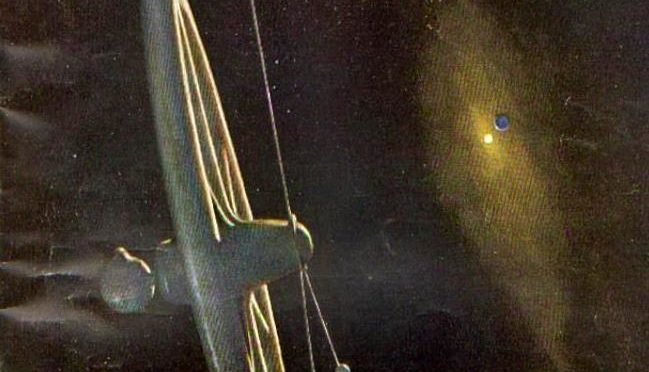

The Geodetic Satellite, by Marvin C. Whiting

The first entry in the magazine is the non-fiction article, and it (thankfully) doesn't involve psi or perpetual motion.

Whiting presents a the history of and need for geodesy. It turns out that geodesy, the science of measuring Earth's exact shape, is essential for navigation — whether nautical, aerial, or ballistic. Satellites allow measurements of incredibly high accuracy, well beyond any military requirement, which means they're almost good enough for scientists. A competent, if not scintillating account. Three stars.

Where I Wasn't Going (Part 1 of 2), by Walt Richmond and Leigh Richmond

A full half of the issue is taken up with the first half of a two-month serial, and thus the trouble starts. The Richmonds were apparently never taught the old maxim: "Show, don't tell." Either that, or the message got garbled in transmission. In any event, while Going is ostensibly about the goings-on in a space station several decades from now, it's really a series of expositional pages that don't even have the virtue of being entertaining.

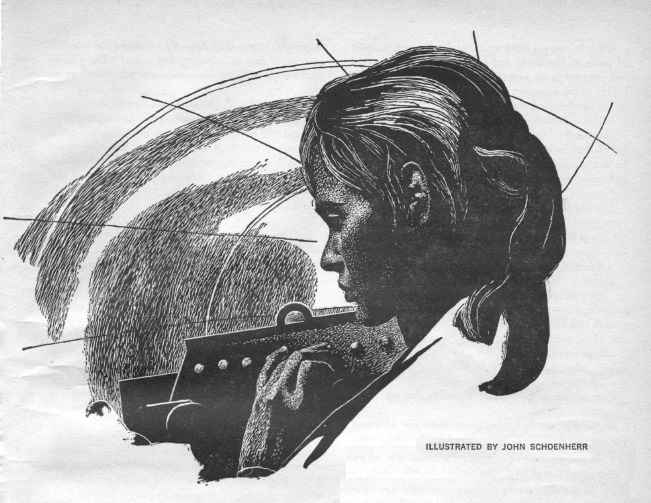

I gave up about a quarter of the way in. It's a pity given the beautiful illustrations Schoenherr produced for the story. One star.

War Games, by Chris Anvil

About a century ago, the Prussian army invented the wargame, a simulation of battle that afforded a modicum of training for officers without any of that messy fighting business. In 1954, Charles Roberts invented the board wargame — a commercial product that does much the same thing, though more cheaply and simplistically.

Anvil posits that we will soon have computerized wargames of incredible detail and flexibility. So good will be these new games that they will replace war as a method of resolving conflicts.

The timing for this piece could not have been better given that I just completed a game of the wargame, Stalingrad. One has to wonder if Anvil is a fellow counter-pusher. In any event, while the plot is nothing special, the depiction of the wargame is marvelous, and I find I must give Wargames a four-star rating. Call it bias.

The Three-Cornered Wheel, by Poul Anderson

Poul Anderson is capable of the most sublime novels as well as the most offensive dreck. Wheel falls somewhere in-between, a little toward the lower end of his range. It's a puzzle piece: how can a shipwrecked vessel transport a spare engine across a thousand miles of rough terrain when the planet's inhabitants find the wheel to be taboo?

Unfortunately, the answer is given away right in the title. The story is uninspired, for the most part, but there are some nifty bits like when young cadet, David Falkayn, hits upon the solution to his problem while being attacked by natives — a nice juxtaposition of action and cogitating. I'll charitably give the yarn three stars though, in truth, it's right on the border of two.

A World by the Tale by Seaton McKettrig

Last up, we meet Earth's first interstellar traveler, a fellow who is given the opportunity to spend a year in Galactic society as a zookeeper for exported terran beasties. His book about his exploits becomes a bestseller throughout the Milky Way, thus providing Earth's first real trade good.

McKettrig (really Randall Garrett in disguise) offers up a reasonably entertaining story, but it's a bit too glib, and the part where the author fails to understand that even a quarter of a percent commission on his book sales will make him a wealthy person indeed, given the size of his market, is implausible. Three stars.

Running these numbers through my personal IBM computer, I come up with a 2.7 star rating, which feels too high. It reminds me of the joke about how to compute "wind chill" — if you feel colder than what you're thermometer reports, fudge the chill factor until it looks right. Anyway, 2.7 is the worst score of the month, being shared by Amazing (interestingly, fellow Traveler John Boston seemed to like his magazine more than the score would seem to warrant). The normally remarkable Fantastic only garnered 2.9 stars. Galaxy got 3.1, F&SF earned 3.3, and British mag New Worlds led the pack with an unusually high score of 3.4.

Women wrote 2.5 of the 29 fiction pieces, a slightly worse average than normal. There was also a paucity of stand-out stories, though Victoria Silverwolf's glowing recommendation of Ballard's The Screen Game warrants attention.

And now it's October, and I have to do this all over again! Wish me luck…

The science article started strong, but he lost me about 2/3 of the way through. Interesting until it wasn't.

"Where I Wasn't Going" wasn't very good, but I did make it all the way through. It has its moments, but it also has problems. The crew of the space station is very multi-ethnic, but a lot of those ethnicities are presented in a rather stereotypical fashion. The worst offender is probably the Chinese scientist who deliberately talks like a fortune cookie and constantly quotes "Confusion". Some of the "science" bits have also clearly been dragged in from some of Analog's more dubious fact articles. The business of using planetary positions to predict solar flares, astrology in general, and I think something else I don't remember. It's no wonder Campbell bought this story.

The Anvil was pretty good. I can see computers being used in this way, particularly with the ability to work on production and resource development in the background. I doubt it will replace war, alas, but it could certainly take games like Stalingrad to a new level (especially being able to combine tactical and strategic games).

I liked the Anderson better than you did. I'd call it a solid three. The title gives the game away, but only if you already know about the geometric figures involved. He also telegraphed it pretty hard when he talked about arcs of up to one third of a circle being permissible. But I bet a lot of readers will learn something new.

Garrett's story was all right, but as you say a bit glib. I'll grant him the author not realizing just how wealthy he was going to be. It requires thinking several orders of magnitude higher than is normal for most people. Realizing that even a poorly selling book is going to sell more copies than Shakespeare multiplied by the Bible is something of a leap.

Re: Richmond, yes I didn't even go into the silly astrology or the ridiculous backstories for the characters. It was a plot outline, not a story.

Re: Garrett, well, it was obvious to me!

> Anvil posits that we will soon have computerized wargames of incredible detail and flexibility

—

Well, he's a science fiction writer, after all… The advent of the transistor lets you put a gate into a semiconductor package the size of a pencil eraser, versus a vacuum tube. But each transistor is a couple of dollars each; more than an hour's pay for most people. And you need *lots* of them to do useful work; several thousand to make the main computing unit, and a few thousand more for working storage. Even the military has trouble justifying that kind of expenditure.

Sure, transistors might eventually cost as little as a dollar each, but you're still left with the massive number of soldered connections on the circuit boards, which cost money. And – this is something that has bitten the missile guidance system guys hard – the statistical incidence of failure of those solder joints goes up out of proportion to the number of joints. The USAF has been waving cash money around for anyone who can come up with a solution, but nobody has pulled a rabbit out of his hat yet.

Sure, a few failed junctions aren't as important for a game as it is got an H-bomb, but you're talking about a piece of equipment that costs more than several new cars, that would be less reliable than a TV set. That's an awful lot of money to expend on some kind of game…

Of the three shorter pieces, I thought the Anderson was the best written. He has a way of creating vivid alien worlds. On the other hand, it was an extreme example of the contrived technical problem story, with cowboys-and-Indians action to fill it up.

The Anvil and the Garrett held no surprises. They both accomplished what they set out to do, in unexciting style.