by Brian Collins

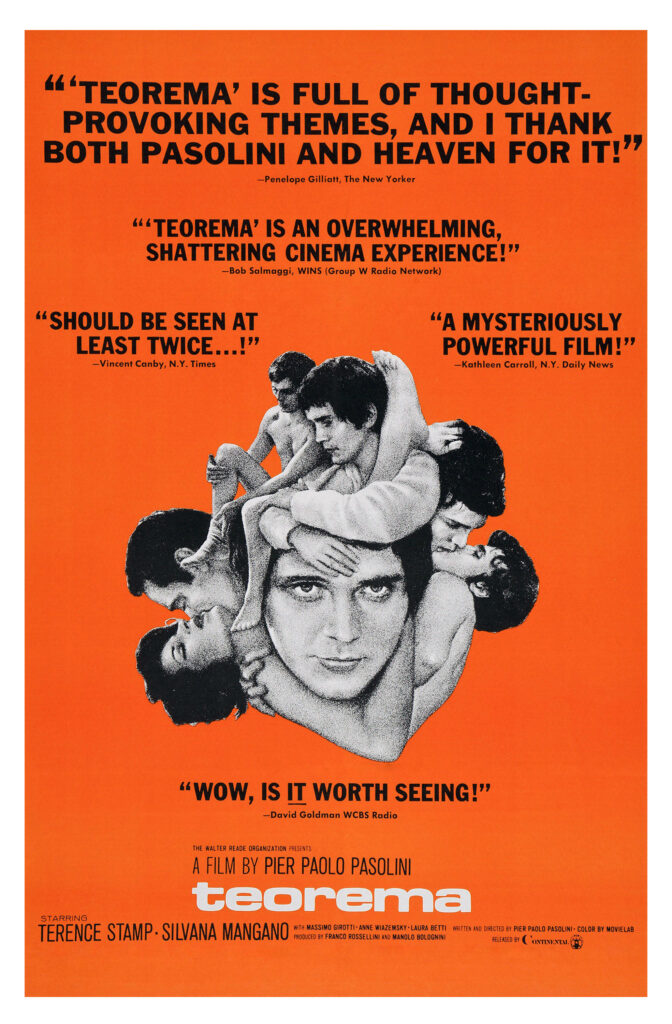

Italian director Pier Paolo Pasolini is quite the character: a provocateur, author, leftist intellectual, and filmmaker. Despite his atheism and devotion to communism, his film The Gospel According to St. Matthew was nominated for multiple Oscars a few years ago, and indeed it's a lovely picture. Now we have Teorema, or Theorem in English, which premiered at the Venice Film Festival late last year to good reception. This is not, at first glance, a "genre" film, although it does have subtle supernatural elements, and like Pasolini's telling of the Jesus narrative it is deeply religiously concerned. It is also a political allegory, and the prudish might take issue with its erotic charge and depictions of homosexuality.

The film starts in a way that doesn't seem to connect with the proceeding plot, but at first glance it does at least make the film's nature as political allegory explicit. We have a documentary-like scene of a union leader being interviewed about something very strange happening recently: a factory owner has given said factory to his workers, seemingly out of a crisis of conscience. We're immediately met with some heady questions, such as: "Is it possible for the bourgeoisie to be transformed in the name of resolving class conflict? Is it even possible for the bourgeoisie to redeem itself, or are such redemptive acts merely the response to a crisis?" We also get a montage of a desert, near a volcano, which likewise seems unrelated to the plot at first.

We then cut to such an upper-class family, a husband (Massimo Girotti) and wife (Silvana Mangano) with their grown children, a son (Andrés José Cruz Soublette) and daughter (Anne Wiazemsky), plus a middle-aged servant (Laura Betti) who lives with the family. (These characters technically have names, but their names are not as nearly as important as the roles they play, so I'll be calling them by the latter.) The family receives a message one day that someone will be arriving soon—maybe for a party at the house that's been planned, but we're not told. We're also not told the name of this person, a handsome visitor played by the young British actor Terence Stamp. The visitor comes and hangs out at the party, but then, for no reason and without anyone objecting, stays with the family for days after the party has ended.

Teorema is a film heavy on ideas and atmosphere, but rather light on dialogue. Viewers might get antsy at the general slowness of it, with the plot on its surface being very simple, and it's common for there to be no spoken dialogue for several minutes at a time. This is just as well. Those who are familiar with Italian productions know that it's customary in that country's film industry to shoot without sound, and then loop dialogue, music, and sound effects in editing. Non-Italian actors speak their preferred languages on-set and then are later dubbed over in Italian. Stamp only has a handful of lines or so, but each time it's clear that Stamp is not the person talking. Similarly Wiazemsky, a French actress, is not the person speaking her lines, and it seems the filmmakers couldn't be bothered to try syncing the dub actress's line reads with Wiazemsky's mouth movements. It's pretty rough dub work.

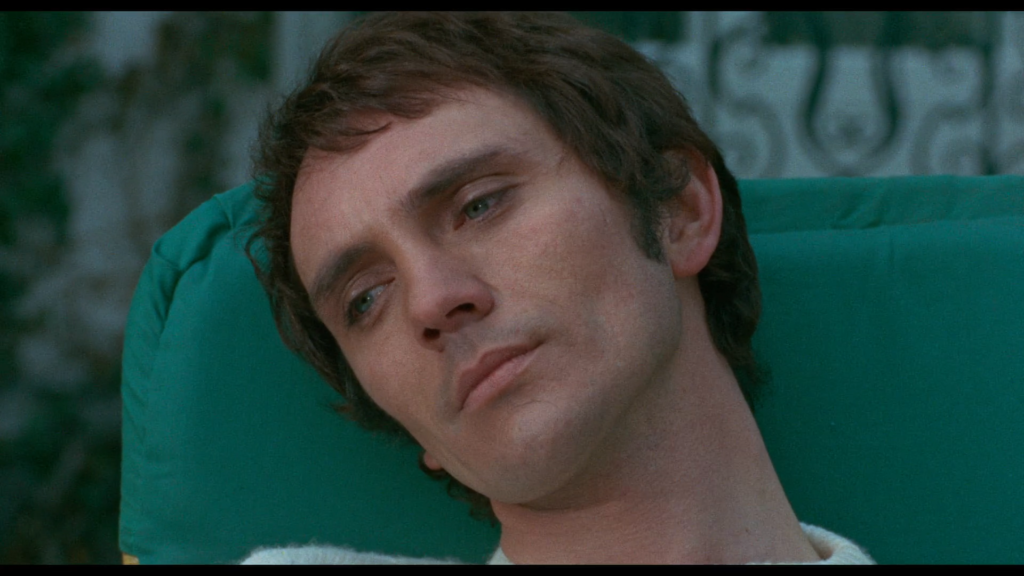

The bad dubbing is occasionally distracting, but it's more than counterbalanced by the film's strong visual language, with Pasolini and cinematographer Giuseppe Ruzzolini working to oscillate between picturesque camera framings and frenzied movements that I have to think were achieved with a handheld camera. The at-times painterly camerawork helps heighten what must be the initial draw for many viewers, which is Stamp's physical beauty—a factor that also draws the members of the family, both the women and men, to him like moths like a flame. The servant is the first to fall under the visitor's spell, so affected is she that after seeing the visitor on the lawn one day she tries to commit suicide. Thankfully the visitor saves her, and not only that, but without any words exchanged between them he makes love to her. It doesn't take long for the mother to be the next "victim" of the visitor's charm, although the strange part of all this is that the visitor doesn't seem to have any ulterior motive for having sex with the people of the household one-by-one.

To call Teorema an erotic film, or "pornographic," or something like that, would be overselling it; but at the same time it does have an eroticism more often found in French and Italian productions as of late than here in the States. We even—dare I say it—at one point catch a glimpse of Stamp's… hot dog (and bun(s)). And yet despite having sex (offscreen) with people of both sexes, the visitor can't be easily categorized as heterosexual or homosexual, or even be said to have much sexual initiative. When he seduces the daughter, for instance, she literally takes him by the hand and guides him to her bedroom, after having taken pictures of him on the lawn. The strange paradox here, that the visitor is a seducer and yet also perfectly gentle with his partners, is that he retains a kind of nobility—even a purity. It's implied, and more or less confirmed later in the film, that the visitor is an angel that has taken on a human guise.

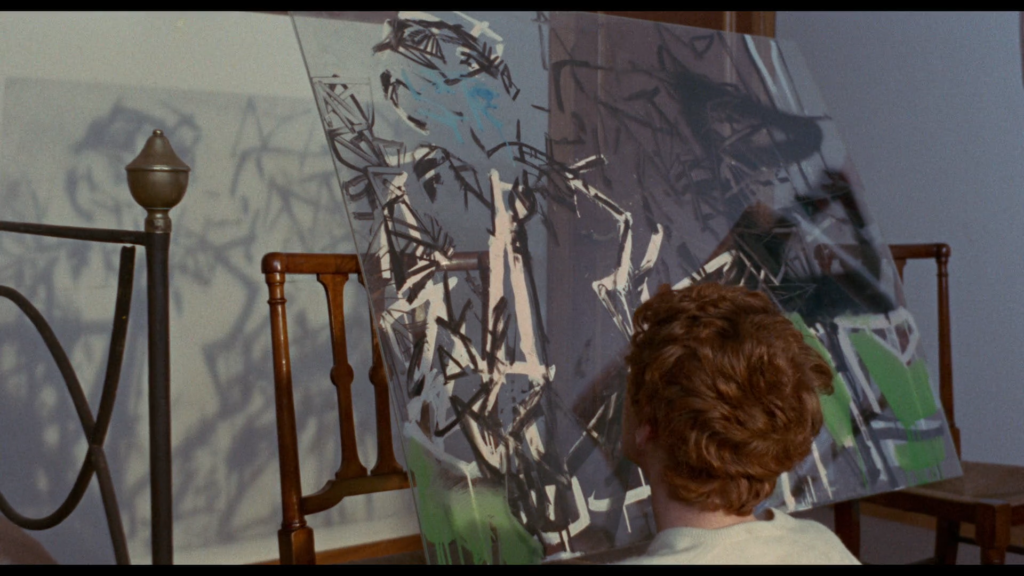

Up to about the halfway point, you could say the film is strange but not outright fantastic—that this is something even more unclassifiable: a somewhat erotic allegory that stands on the borderline between the real and the fantastic. But then, for no reason given, the visitor leaves. Clearly the family were expecting him to leave at some point, but the reality of the visitor finally leaving them (presumably forever) hits each of the household members like a truck. The daughter, perhaps being driven mad from keeping pictures of the visitor in a photo album, enters a catatonic state and is driven off to a mental hospital. The son gets out of this situation the best, having taken up painting as a hobby, his fate maybe aligning most with what Pasolini considers the best-case scenario for the bourgeoisie being transformed. The mother starts whoring herself out to young men who eerily resemble the visitor, yet she's unable to fill the hole the visitor had left in her life. The servant leaves the estate and returns to her native village, where she becomes a sort of prophet who can work miracles.

Teorema is about 95 minutes long, and is split pretty close to evenly in half, between the visitor's stay and after he leaves. As such it doesn't have the three-act structure that we've come to expect from narrative filmmaking so much as two long acts, or maybe even six acts, with each half of the film having its own three-act narrative arc. Those who came to see Terence Stamp both will and will not be disappointed, since sadly he does leave halfway through the film, but he does make the most of what screentime he has, even with how few lines he is given. Once the visitor leaves, both the characters and the structure splinter, with the second half of the film being concerned with each of the members of the house trying to cope with the visitor's absence in different ways, with varying degrees of success. Curiously, the servant, the only one to come from a working-class background, is also the only one who seems to have been "blessed" by the visitor, resulting in the film's only overtly supernatural moments.

When it comes to what little dialogue there is, most of it is taken up by a few extended monologues, one of which especially caught my attention. The father at one point takes a passage from the Book of Jeremiah, although it looks like Pasolini abridged it somewhat and reworded things for his own ends. Here is the passage from the King James translation, Jeremiah 20:7 to 20:10:

O LORD, thou hast deceived me, and I was deceived: thou art stronger than I, and hast prevailed: I am in derision daily, every one mocketh me.

For since I spake, I cried out, I cried violence and spoil; because the word of the LORD was made a reproach unto me, and a derision, daily.

Then I said, I will not make mention of him, nor speak any more in his name. But his word was in mine heart as a burning fire shut up in my bones, and I was weary with forbearing, and I could not stay.

For I heard the defaming of many, fear on every side. Report, say they, and we will report it. All my familiars watched for my halting, saying, Peradventure he will be enticed, and we shall prevail against him, and we shall take our revenge on him.

And here is the father's monologue:

You have seduced me, O Lord, and I let myself be seduced. You have taken me by force, and you have prevailed. I have become an object of daily derision, and all mock me. Yes, I have heard the defaming of many, terror on every side. “Denounce him, and we will denounce him.” All my friends awaited my downfall. “Perhaps he will let himself be seduced. Then we shall prevail, and take our revenge upon him.”

There is a great deal that can be said about Pasolini's replacing "deceived" with "seduced," or the fact that the recontextualizing of the passage gives man's relationship with God a homoerotic implication. This is all an ambitious gambit for Pasolini, to combine the religious, political, and erotic, into a single concise narrative.

Speaking of the father, we finally learn about the context for the film's opening scenes, with the union leader and the desert. It turns out that the father is the factory owner who has given his property over to his workers, and also that he has humiliated himself in public by stripping naked in the middle of a train station. He sheds his material possessions about as far as humanly possible, and yet even as he wanders naked through the desert (how he got from the train station to the desert on foot is anyone's guess), it's clear that this relieving of wealth does not absolve the father, nor does it bring him happiness. The ending, strange as it is, is up to interpretation, but I have a feeling Pasolini believes it's impossible for the bourgeoisie to redeem itself.

I believe it was John W. Campbell who, many years ago now, said that if the stars appeared only once in a thousand years that men would surely go mad at the sight of them. (Of course I'm also referring to a certain beloved SF story, although I need not tell you its title.) Similarly, in Pasolini's film, the bourgeoisie are suddenly made aware of their own insignificance because of one divine and beautiful man. (I do not mean to say I find Terence Stamp attractive, although I do think it's fair to say, as an objective statement, that he is quite attractive. Yes.) It's a film about confronting the fantastic and turning to dust because you are unworthy of such a sight. It's a challenging film, maybe a bit too slow and structurally off-kilter, but I have to admit I also found it enticing.

Four stars.

It sounds fascinating. I do like Terrence Stamp…

~Gideon

Oh, well played, sir! Well Played!

You managed not only to review Pasolini's TEOREMA on a SF review site, but also to cite the words of John W. Campbell** to support your conclusion about the Pasolini.

** Though Campbell was quoting Ralph Waldo Emerson, it should be noted.

More accurately Campbell was responding to an Emerson quote, which Asimov would then use for a certain story.