[The second Galactoscope for this month features a pair of new novels we felt we could not in good conscience leave unreviewed, particularly the latter. Enjoy this last review of books before the New Year!

by Victoria Silverwolf

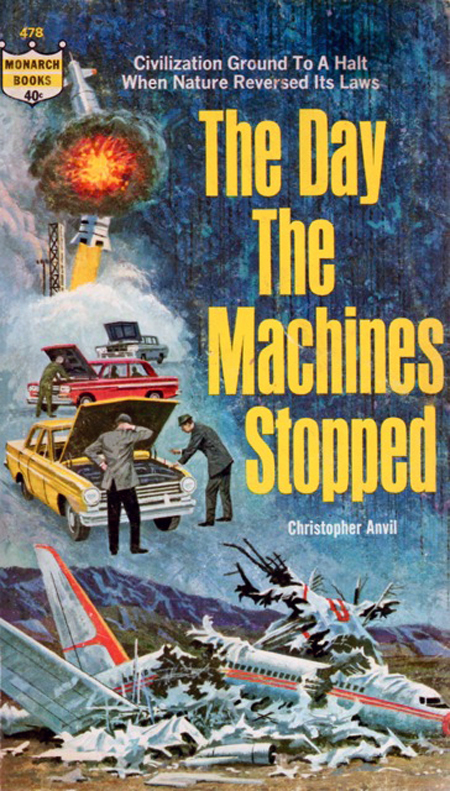

The Day the Machines Stopped, by Christopher Anvil

Cover art by Ralph Brillhart

The Anvil Chorus

Christopher Anvil is the pseudonym of Harry C. Crosby, who published a couple of stories under his real name in the early 1950's. After remaining silent for a few years, he came back with a bang in the late 1950's, and has since given readers about fifty tales under his new name. His work most often appears in Astounding/Analog.

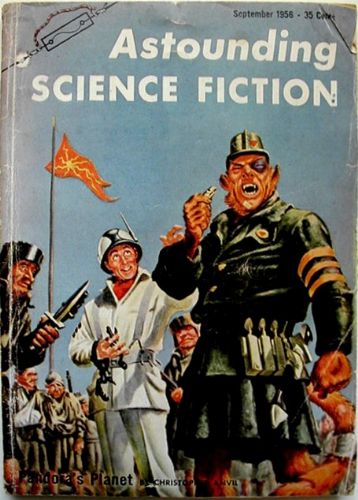

A typical Anvil yarn is a lightly comic tale about clever humans defeating technologically advanced but naive aliens. Perhaps his best-known story is Pandora's Planet (Astounding, September 1956), the first of a series of humorous accounts of the misadventures of lion-like aliens trying to deal with the chaos caused by those unpredictable humans.

Cover art by Frank Kelley Freas

The Day the Machines Stopped is his first novel. (At only 120 pages of text, I'm guessing it's well under 40,000 words, so it might be considered a long novella.) With its near-future setting, lack of space travel or aliens, and almost entirely serious tone, it's quite different from his usual creations.

The Eternal Triangle in the Science Lab

The first page of the book sets up a romantic conflict. Brian Philips, our protagonist, is a chemist for a research corporation. Carl Jackson is an electronics expert for the same company. They are both interested in Anne Cermak, who works with Brian. Carl is bigger, richer, and more used to getting his own way than his rival. Brian is a nicer guy, of course, and has the decency to admit that it's up to Anne to choose which of the two men, if either, she prefers.

Before we get too deep into this soap opera plot, we get our reminder that this is a science fiction novel. A news report on the radio reveals that a Russian scientist has defected to the West. He claims that an experiment in cryogenics at a Soviet facility in Afghanistan threatens civilization. It isn't very long before he proves to be right.

Who Turned Out the Lights?

Somehow or other, the experiment causes electricity to fail. Fully charged batteries provide no power. Automobiles stop dead in their tracks. (Diesel trucks still operate, but only when their electric starters are replaced by another kind of technology.) Working together despite their rivalry, Brian and Carl explore the surrounding area on bicycles. Things are the same all over, it seems.

The president of the research corporation, James Cardan, sees bad times coming. He manages to assemble firearms, provisions, and other supplies. His plan is to take his employees and their families, in a caravan of diesel trucks, to the northwest part of the United States, which he assumes will be safer than more populated areas.

Two Against Chaos

Without giving too much away, let's just say that circumstances cause Brian and Anne's father to miss the caravan. They set out on their own on bicycles, hoping to catch up to the others. (Due to frequent roadblocks caused by stalled cars, this isn't too unlikely. The diesel trucks are also slowed down by frequent stops for repairs.)

As expected, the breakdown in technology leads to bands of armed bandits, desperate for survival, battling over food. After many dangerous encounters, the pair of two-wheeled adventurers join Cardan's group.

Duking it Out

The caravan runs into a large, heavily armed, well-organized army, under the command of a man wearing a silver crown. He proclaims that the surrounding countryside, now known as the Districts United, is under his protection. He will punish those guilty of killing, arson, robbery, and bushwacking. (These specific crimes are listed under the acronym karb.) He calls himself the Districts United Karb Eliminator, or Duke. (This bit of satiric wordplay is one of the few traces of wit in the novel.)

Obviously, he's a megalomaniac, but he's a smart and effective one. Many survivors of the disaster are willing to place themselves under his dictatorship, given the alternative of fighting violent criminals. Brian, having few other choices, winds up working for the Duke, rebuilding steam engines, biding his time until he can escape with the rest of Cardan's group.

Worth Reading by Candlelight?

Anvil's style is plain and straightforward, so the book is very readable. His depiction of what would happen if electric power vanished is convincing, although the scientific explanation for why this happens is vague. The romantic subplot is less believable. The hero sometimes comes across as a ninny, given his willingness to trust someone who has already betrayed him. The ending comes as something of a deus ex machina. Overall, the novel is worth spending four dimes and two hours reading, but it's unlikely to become a classic.

Three stars.

By Rosemary Benton

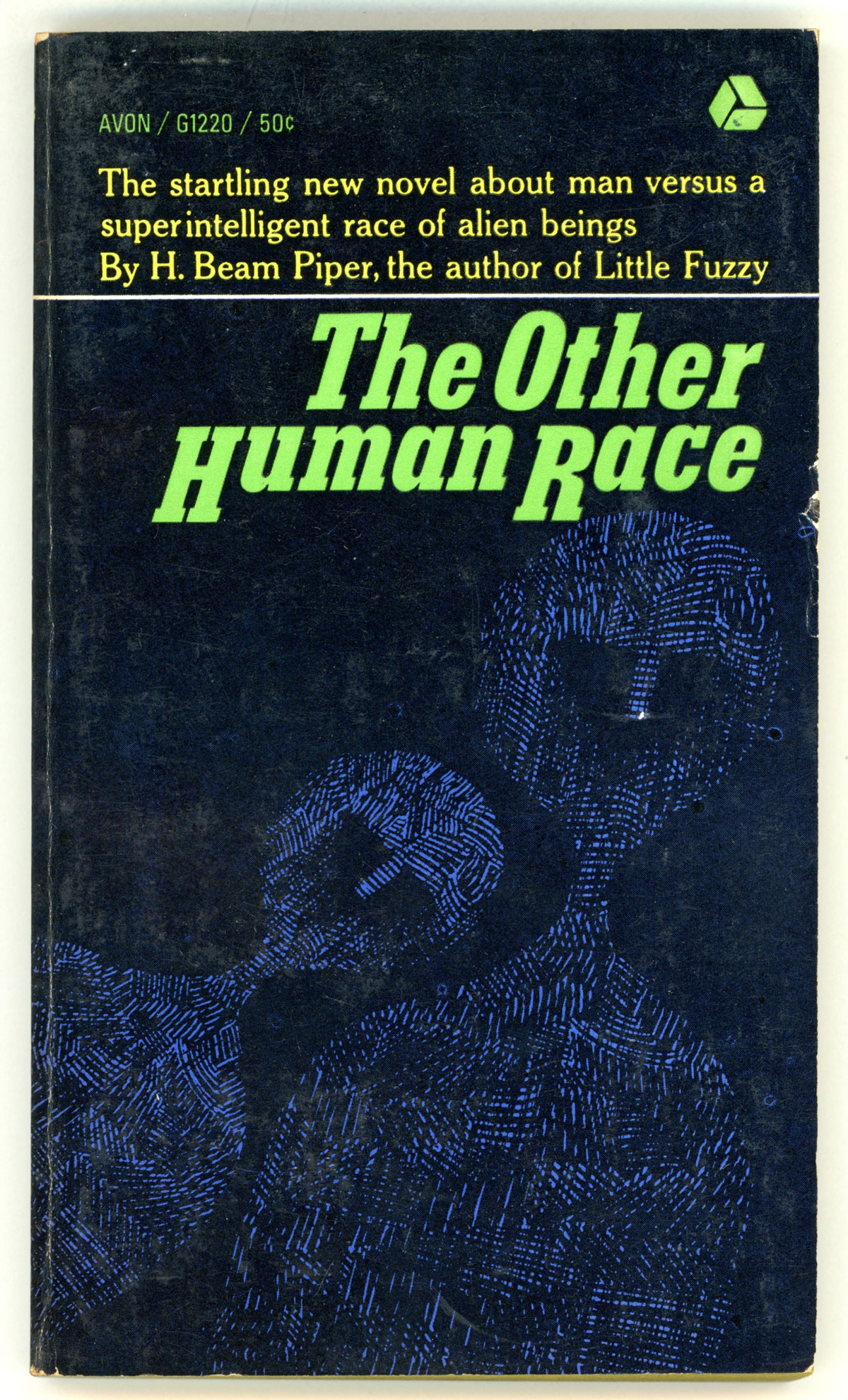

The Other Human Race by H. Beam Piper

I could not be more happy with science fiction nowadays. On television we have shows like The Twilight Zone that are stretching the boundaries of story telling, and exploring new topics in a science fiction setting. In literature we have authors like H. Beam Piper who integrate a veritable cornucopia of academic fields into their stories about human exploration.

This is not the cut and dry kind of science fiction where it's us or them in a race for survival. Piper's books approach space exploration with a touching level of humanity and compassion. Alien and human language, diet, population demographics, social structures, and more are all examined and dissected by Piper's characters. His burgeoning "Little Fuzzy" series, following the success of his 1962 novel "Little Fuzzy", is a brilliant example of the ability Piper has to consider the humongous ramifications and complications of humanity contacting alien civilizations.

Fuzzies, Fuzzies Everywhere

"The Other Human Race" picks up mere weeks after the explosive conclusion "Little Fuzzy". Having been granted the universal recognition of "sapient", the fuzzies' home world of Zarathustra has been granted independence from the Chartered Zarathustrian Company. Word of the sensational trial has begun spreading like wildfire throughout human colonized space. But the fuzzies' new found notoriety has brought both altruistic and enterprising humans to Zarathustra.

On one side are the people who want to integrate the fuzzies into the wider galactic civilization while keeping their dignity and safety in mind. This includes linguists, psychologists, nutritionists and other "Friends of the Fuzzies" who see value in the fuzzies as people, not animals. In contrast are those who would exploit the naive little people, as well as those who want to fill the power vacuum left by the CZC. Worst of all is the pressing concern about the kidnapping and enslaving of fuzzies to sell as pets in an illegal off-planet black market.

Things Just Got More Complicated

Piper balances that marvelous rush of scientific discovery in "Little Fuzzy" with a a weighty maturity in "The Other Human Race". While our protagonists take immense satisfaction with their continued study of the fuzzies, they bear a weighty responsibility. It inevitably comes down to them to make sure that the fuzzies’ quality of life is not sacrificed in humanity's drive to conserve the species.

Now that fuzzies have been made known to the universe, they face predators more devious and cunning than the native species of the planet. How can the Commission of Native Affairs go forward with plans to have humans adopt fuzzies and still protect them once a fuzzy is situated with a new human family?

The issue of the fuzzies' high infant mortality rate is also complicating things. To study why this is happening the group stationed on Zarathustra have to keep a miscarried fuzzy for study, despite the distress this causes the local fuzzy population. Their limited diet and off-balanced internal biology are also a tricky problem to study since the team can't just cut into a fuzzy and study its internal organs. Nor can they subject a fuzzy to a battery of tests to see how it reacts under certain stressors.

That same maturation is present in the character arcs of the cast. Those who were opposed to the recognition of the fuzzies as sapient in the first book are not permanently cast as evil. Instead, they change their attitudes towards the fuzzies with exposure to the little aliens. For instance, Victor Grego very early on in "The Other Human Race" comes across a fuzzy who has been scrounging around in his company's headquarters. After spending time with a member of the species that cost him access to the valuable resources on Zarathustra, Victor comes to realize that fuzzies are actually wonderful companions.

Our protagonists, including Jack Holloway and Ruth van Riebeek, must go through their own paradigm shift regarding those who were once their enemies. The grace with which some of these characters accept their former enemies as allies is laudable. Those employees of the now-charterless Zarathustra Company were acting in the interest of protecting their investments and livelihoods. But if they are willing to adapt and redeem themselves then, CZC or not, they should be congratulated and welcomed for their change of heart.

A Fragile New Sentience

H. Beam Piper's writing is altogether very touching. It's optimistic, but realistic in its acceptance that once something has been put in motion it will become infinitely more complicated. At the same time he seems to adhere to an inevitable sense of justice in his written worlds. Like a progressive modern scientist, Piper strongly advocates for the naturally given right people have to happiness and safety. All of his characters are entitled to it, and those who abuse or try to take away that right from others always get their just deserts.

Piper's writing continues to impress, and seems to be gaining more and more depth with each new novel. His "Little Fuzzy" series in particular has a lot of promise, and I hope to see more installations in the near future.

Five stars for Piper's well written sequel and masterfully built world.

[We are sad to have learned of H. Beam Piper's tragic passing just a few weeks ago. The genre has lost one of its brightest lights.]

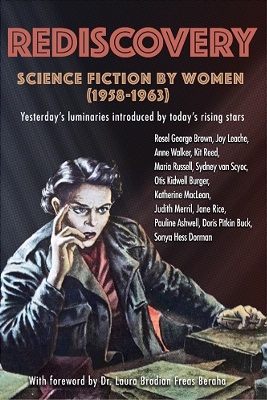

[Holiday season is upon us, and Rediscovery: Science Fiction by Women (1958-1963) contains some of the best science fiction of the Silver Age. And it makes a great present! A gift to friends, yourself…and to the Journey!]

I'm so sorry to hear about H. Beam Piper. I loved his Fuzzy series and his loss is a huge blow for the genre.

Piper is a huge loss to the field. He had so much more to tell us, about the Fuzzies, about Lord Kalvan, about things we'll never know. Just awful.

Piper's death is a tragic loss to science fiction. He wrote his characters with a sense of hope, formed his world around a belief that everything would turn out better in the end, and it's a terrible shame that he couldn't bring those rays of light to his own life. He will be missed, but thankfully his works will continue to be released posthumously.