by Gideon Marcus

Mars or Bust

This week, humanity embarked on its most ambitious voyage to date. Its destination: Mars.

I use the term "humanity" advisedly, for this effort is a global one. On November 28, 1964, the United States launched Mariner 4 from Cape Kennedy. And just yesterday, the Soviet Union's Zond hurtled into space. Both are bound for the Red Planet, due to arrive next summer.

That both missions commenced so close to each other was not a coincidence. Every two years, Earth and Mars are situated in their orbits such that a minimum of energy can be used to get from one planet to the other. This favorable positioning applies equally to democracies and communist states.

Mariner 4 and Zond are not the first Martian probes: identical Mariner 3 was lost a few weeks ago, and Zond's predecessor, Mars 1, failed a couple of months before it could reach its target. Let us hope these new spacecraft have more luck. So far so good!

It is possible that these two probes will revolutionize our understanding of Mars, just as Mariner 2 changed our view of Venus forever. It is, therefore, appropriate that I summarize our knowledge of the planet on the eve of collecting this bonanza of new information.

Another Earth?

Mars has been known to us since ancient times. Because it wanders through the constellations throughout the year, it was classified as a "planet" (literally Greek for wanderer). When it is in the sky, it is one of the brightest objects in the sky, with a distinct reddish tinge, which is why it has been associated with the bloody enterprise of war.

Until the invention of the telescope, all we knew about the fourth planet from the Sun was its orbital parameters: its year is 687 days, its path around the sun very circular, and its average distance from the Sun is around 141,600,000 miles.

Even under magnification, Mars can be a stubborn target; at its nearest, about 35 million mies away, the planet measures just 25 seconds of arc from limb to limb (compared to the Moon, which subtends 1860). Still, early telescopes were good enough to resolve light red expanses, darker expanses (believed to be seas), and bright polar caps. Said caps waxed and waned with the Martian seasons, brought on by the planet's very Earthlike tilt of 25 degrees. Because the Martian surface was visible, unlike those of Venus or Mercury, the day was calculated to be just over 24 hours long. Indeed, Mars appeared to be a world much like Earth.

Mars for the Martians

In 1877, our understanding of the planet broadened. Astronomer Asaph Hall discovered two tiny moons, named Phobos and Deimos, and we were able to deduce the mass of Mars — about 10.7% that of Earth. Combined with the planet's diameter of 4200 miles, that meant Mars' density was about four times that of water. This is only two thirds that of the Earth, which suggests that the planet is poorer in heavy metals, and/or that, because the planet is less massive overall, its layers are not so tightly bound together with gravity. From Mars' measured mass and diameter, we learned that the surface gravity is 38% that of Earth; sprinting and jumping should be much easier there. Flying…well, more on that in a moment.

1877 was also the year that Mars came into our public consciousness in a huge way — all because of a silly mistranslation. Giovanni Schiaparelli turned his 'scope to Mars and saws something remarkable: dozens of fine straight streaks crisscrossing the planet that seemed to link up the dark patches (which were, if not oceans, at least areas of vegetation suggesting the existence of water). He called them canali, which is Italian for "channels". But to English ears, it came out as "canals", which strongly connotes construction by intelligent beings.

Well, you can see what an uproar that would make. Very soon, folks like Wells and Burroughs were writing tales of Martian aliens. And not just aliens — civilizations beyond those found on Earth. The thinking went that the planets' ages corresponded to their distance from the Sun. Hence, Mercury was a primordial hunk of magma. Venus, shrouded in clouds, was probably a steamy jungle planet on which Mesozoic monsters roamed. And beyond the Earth, Mars was a cold, ancient world, its verdant plains dessicated to red deserts. To avoid catastrophe, the Martians built planet-spanning canals to bring water to their cities. Being so advanced, it was obvious that they had mastered space travel, and had either visited us or were on the verge of doing so.

Even the more practical-minded scientists were hungry for evidence of life, even primitive stuff, existing off of the Earth. Mars seemed like the prime location for extraterrestrial creatures to be found. For one thing, the planet clearly had an atmosphere, wrapping the planet's edges in a haze and producing a marked twilight.

Originally thought to be a touch thinner than Earth's, more recent measurement of the polarization of Martian light (the vibration angles of light reflected off the atmosphere) suggested that the surface air pressure was about 8% that of Earth. That was too thin for easy breathing, but not too thin for life. If there was enough oxygen in the mix, perhaps a person could survive there.

Mars Today

Such was our understanding of the planet perhaps a decade ago. Recently, ground-based science has made some amazing discoveries, and it may well be that Mariner and Zond don't so much revolutionize as simply enhance our understanding of the planet.

I just read a paper that says the Martian atmosphere is about a quarter as dense at the surface that thought. This isn't just bad for breathing — it means NASA scientists have to rethink all the gliders and parachutes they were planning for their Voyager missions scheduled for the next decade. Observations by spectroscope have found no traces of oxygen and scarcely more water vapor. The planet's thin atmosphere is mostly made up of nitrogen and carbon dioxide. The ice in the polar caps may well be mostly "dry".

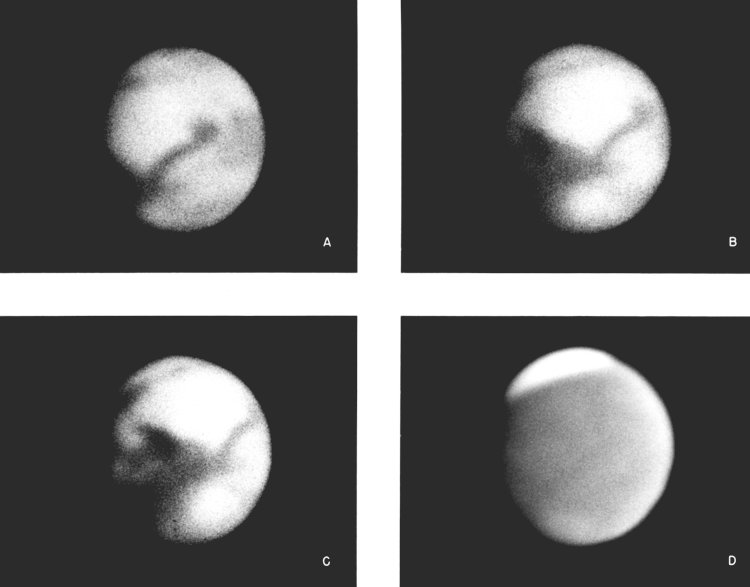

Because of the lack of water and the thin air, erosion is probably much less of a factor on Mars. In a recent science article in Analog, George Harper says that the planet's surface may be riddled with meteorite craters that never got worn away. Close up, Mars may end up looking more like the Moon than the Earth!

And those canals? Telescopic advances in the late 40s made it possible to examine Mars in closer detail than ever before. The weight of astronomical opinion now disfavors the existence of canals.

Still, old dreams die hard. I imagine we will cling to our visions of Martian life and even civilizations long after such notions are proven unworkable. To kill such fancies, it'll take a blow as serious as that delivered by Mariner 2, which told us that it's hot enough to melt lead on the surface of Venus.

We'll find out, one way or another, in July 1965!

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

Thanks for a very informative article.

I doubt we'll find any golden-eyed Martians, but maybe it's not too much to hope for some form of microscopic life on the red planet.

Terrific post. Looks like will have to make the most of what we've got here on Earth.

It was so nice to meet you, today, Mike! Thank you for joining us in 1964!

If only Mariner 4 had flown over the interesting side of Mars, the one with the giant volcanoes and canyon system! Then again, Mariner 6 and 7 imaged them in 1969 and scientists still didn't get what they really were. Nix Olympia – later Olympus Mons – was thought to be "just" a 300 mile-wide impact crater.

And if you go slightly into the future to obtain a copy of the December, 1967 issue of National Geographic Magazine, you will see that Mars was still being depicted as having canals.