by Victoria Silverwolf

The planet Mars and its inhabitants have long been favorite themes for science fiction writers, from The War of the Worlds to The Martian Chronicles. Will the age of space travel put an end to our wildest fancies about that alluring world?

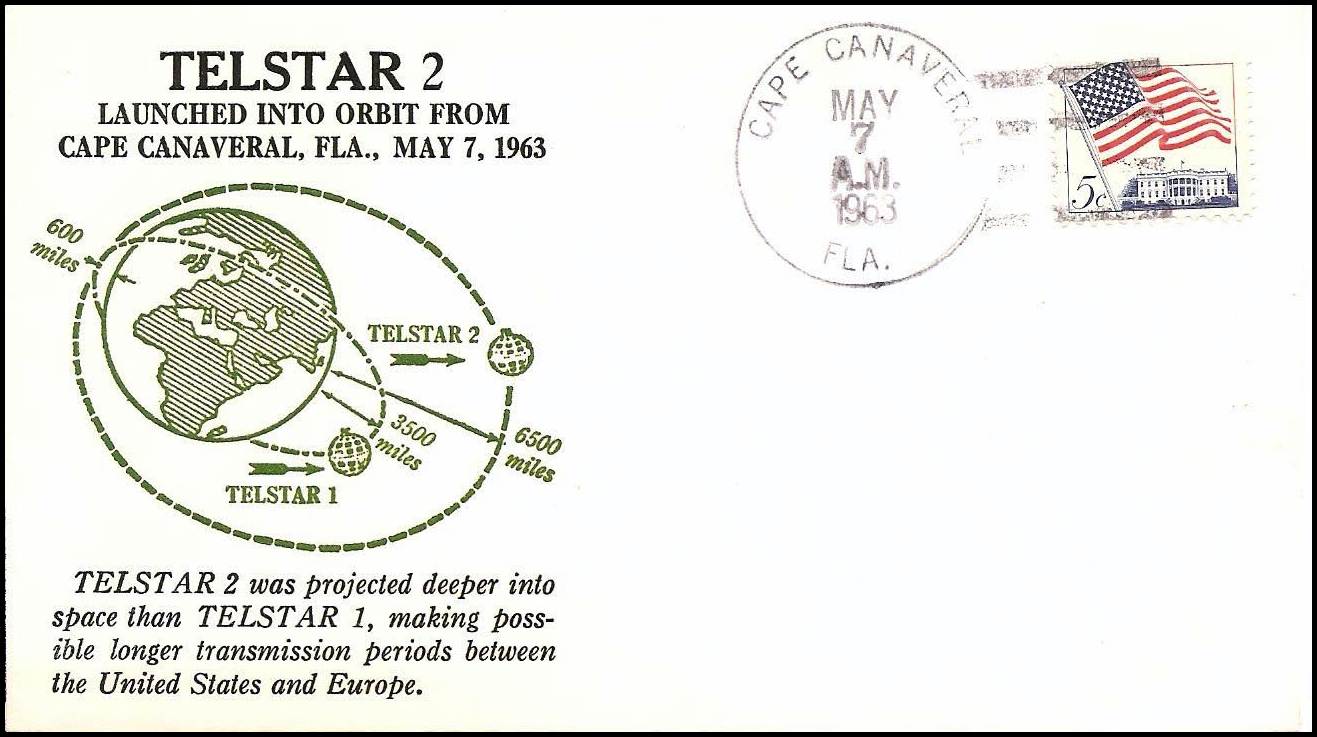

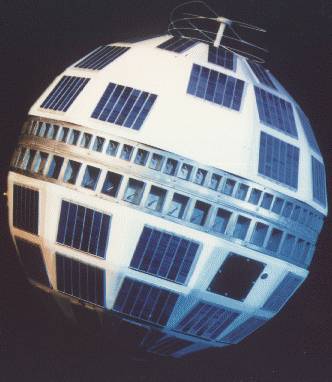

The Soviet spacecraft intended to study Mars have all failed. NASA's Mariner program, so successful in studying Venus, is not scheduled to turn its attention to Mars until next year. Because the red planet is still something of a mystery, authors are free to use their imagination for a while yet. They may create a world where humans can live, or depict Martian canals and the civilization that created them.

The third issue of Worlds of Tomorrow upholds this tradition, with the first section of a major new novel set on Mars.

All We Marsmen (Part 1 of 3), by Philip K. Dick

The latest work from the author of last year's critically acclaimed alternate history novel The Man in the High Castle (which got only a mixed review from our esteemed host) is set on a traditional version of Mars. There are humanoid Martians (called Bleekmen), although they are a dying people. There are canals, although they are in a poor state of repair. Humans can survive on the planet, but only under harsh conditions.

By the end of this century, human colonies exist on Mars. Founded by Earth countries, businesses, or labor unions, they are under the control of the United Nations. Against this background, the reader is introduced to several characters.

Silvia Bohlen is a housewife and mother. She takes barbiturates to sleep and amphetamines to wake up. Her husband Jack is a repairman. While flying out on an assignment to fix a refrigeration unit, he gets a call from the UN to aid a group of Bleekmen dying of thirst. During this errand of mercy he meets Arnie Kott, head of an important union, whose own helicopter flight has been interrupted by the emergency. Kott despises the Bleekmen, and argues with Jack about the need to help them. Despite this disagreement, he comes to respect Jack's skill, and hires him for an important repair. In a flashback sequence, we learn that Jack came to Mars after an episode of schizophrenia.

Norbert Steiner and his family live next to the Bohlens. He works as a health food manufacturer, and secretly imports forbidden luxury foods from Earth. His son Manfred is severely autistic, and lives at a special facility for children with mental or physical disabilities. A shocking event involving Steiner leads to a crisis for his family and his neighbors.

There are many other characters I haven't mentioned and multiple subplots. It's not yet clear what direction this novel is going. There are hints that schizophrenics and autistics have precognitive abilities, and I believe this will be a major theme.

Some readers may be dismayed by the lack of a simple, linear plot. Others will find the novel depressing, as so many of its characters are unhappy with their lives. The picture it paints of a Mars inhabited by a large number of humans by the 1990's is likely to seem unrealistic. However, the author appears to have created a complex, serious work of literature, worthy of careful reading. Four stars.

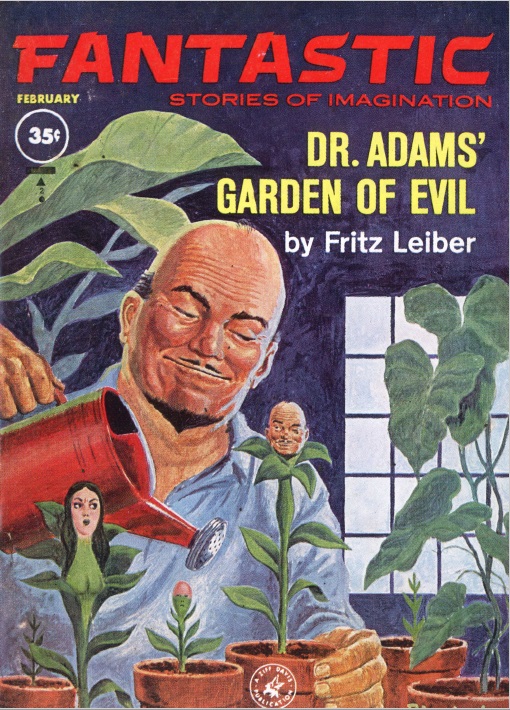

A Hitch in Space, by Fritz Leiber

In a distant solar system, two men are aboard a spaceship on a routine mission. One of the men develops a bizarre psychosis. He imagines that his partner, the narrator, is really two people. When he's around, he calls him Joe, and thinks of him as a hero. When he's gone, he speaks to the imaginary Joseph, and insults him. The narrator puts up with this weird delusion, but when he goes outside the ship, the situation becomes dangerous.

This story combines psychological drama with a technological puzzle that could have appeared in the pages of Analog. As you'd expect from this author, it's very well written. The situation is interesting, if somewhat artificial. Three stars.

To the Stars, by J. T. McIntosh

A manufacturer of starships is blackmailed, on the basis that his ships are more dangerous than others. He disposes of this threat easily enough, with evidence that they cause no more deaths than any other ships. What is kept secret, however, is the fact that his ships are vulnerable at a particular moment during their time of use. When his daughter leaves on her honeymoon aboard one of his ships during this hazardous time, he takes measures to prevent a possible disaster.

I found the plot of this story contrived and inconsistent. The female characters are more fully realized than usual for this author. Unfortunately, the effect is ruined by an irrelevant paragraph explaining that women will never be equal to men in the business world, even two centuries from now. The reasons given are "women never trusted women" and "women didn't really want equality." Two stars.

The New Science of Space Speech, by Vincent H. Gaddis

This article discusses research into ways to communicate with extraterrestrials. It covers a lot of ground, from radio telescopes to dolphins, and from artificial languages based on mathematics to unexplained radio echoes. Some of this material is interesting, but the author covers too many subjects in a short space to do more than offer a taste of them. Two stars.

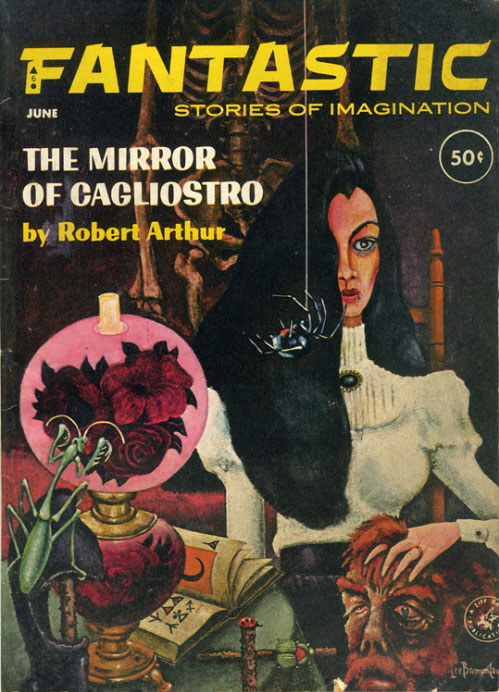

A Jury of Its Peers, by Daniel Keyes

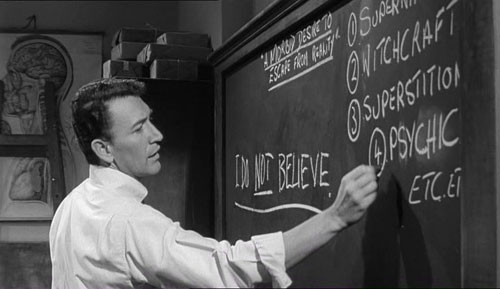

A professor of physics invents a small computer that has consciousness. During a lecture he tells the students that the computer can think, forgetting that the state has passed a law against making such a claim in the classroom. A trial follows, with the computer itself called as a witness.

This scenario is clearly based on the famous Scopes Trial of 1925, which tested the law against teaching human evolution in Tennessee schools. Ironically, the law against teaching machine intelligence is in New Jersey, and the lawyer defending the professor is from Tennessee.

If this were merely an allegory for academic freedom, the story would be only moderately effective. However, the author has more in mind. The professor must face his own limitations, as well as those of the computer, when it gives its testimony. Although not the masterpiece one might expect from the creator of Flowers for Algernon [If he had a nickel for every time a reviewer said this…(Ed.)], this is a fine story with depth of characterization. Four stars.

The Impossible Star, by Brian W. Aldiss

Four astronauts explore the region of space beyond the Crab Nebula. A problem with their spaceship strands them on a small, rocky planetoid near a star of such immense mass that not even light can escape from it. (This may seem fantastic, but in recent years physicists have speculated that an object of sufficient size could produce a gravitation pull so strong that this could happen.) The men struggle with the bizarre effects of the black star. The stress of their situation soon has them at each other's throats. The concept is an interesting one. Even in an issue full of downbeat stories, this is a particularly bleak tale. Three stars.

Until the Mariner project takes away our dreams of glittering Martian cities, rising from ruby sands along emerald canals, let's keep reading about that fascinating world in the pages of our Earthling magazines.