by Victoria Silverwolf

If any more proof is needed that rock 'n' roll now dominates the American popular music scene, here it is: a couple of days ago, radio station KMPX in San Francisco (106.9 on your FM dial, for those of you near the city by the bay) started playing a wide variety of rock music (as opposed to the usual Top Forty hits) twenty-four hours a day. As far as I know, it's the first station in the USA to do so.

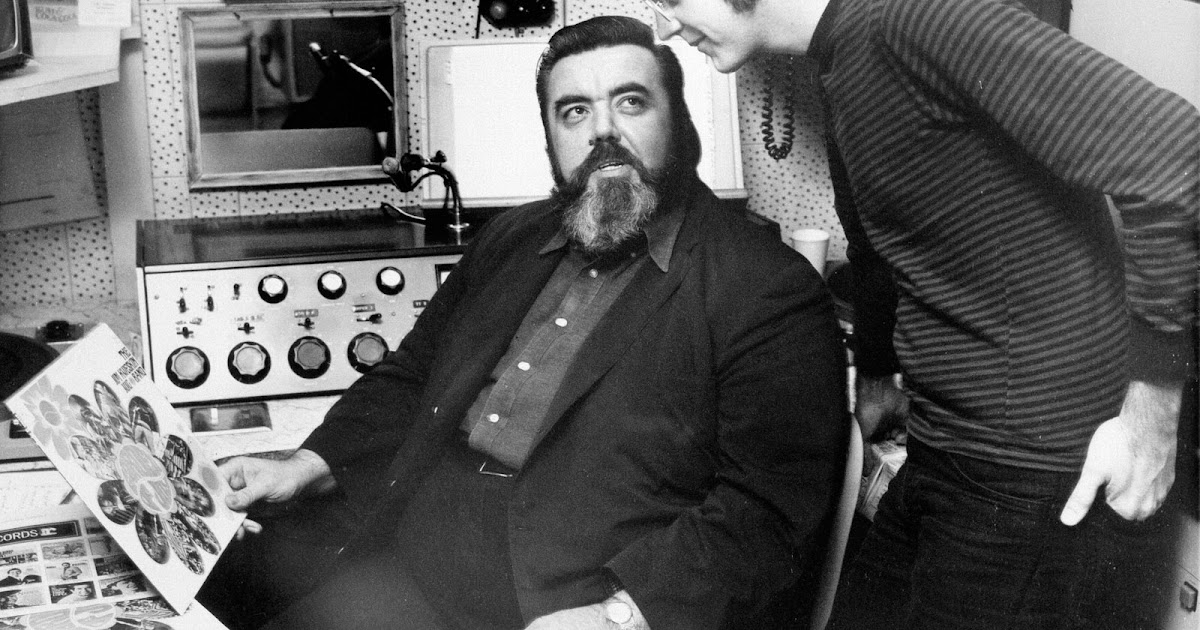

Tom "Big Daddy" Donahue, programming director for KMPX.

I live a very long way from Frisco, so I won't be able to pick up their signal.

Appropriately, the lead story in the latest issue of Fantastic features the inability to establish contact over a vast distance as a major plot point. As we'll see, other stories in the magazine also deal with difficulties in communication.

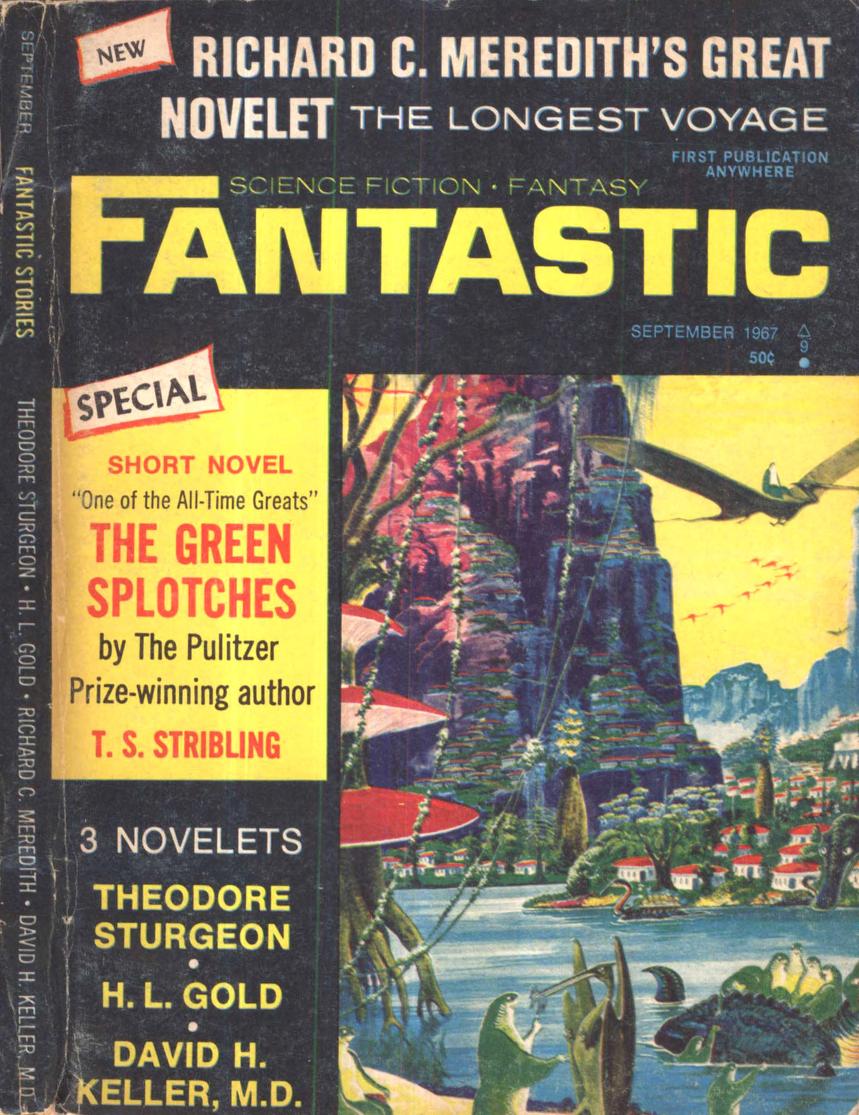

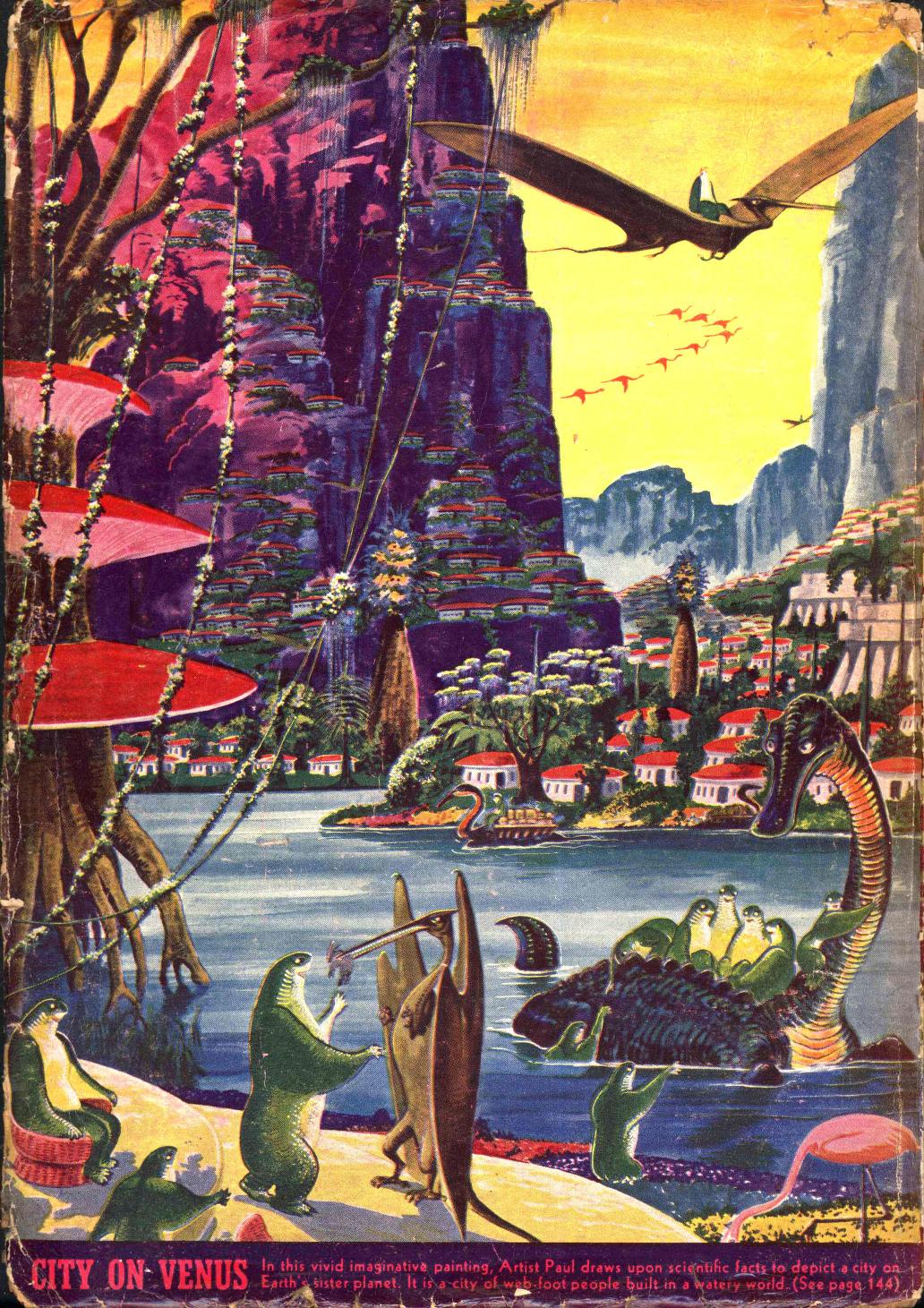

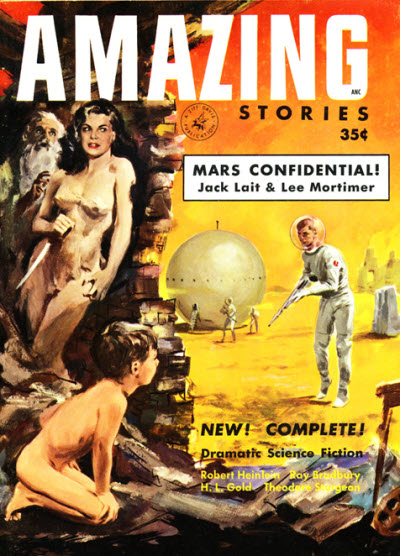

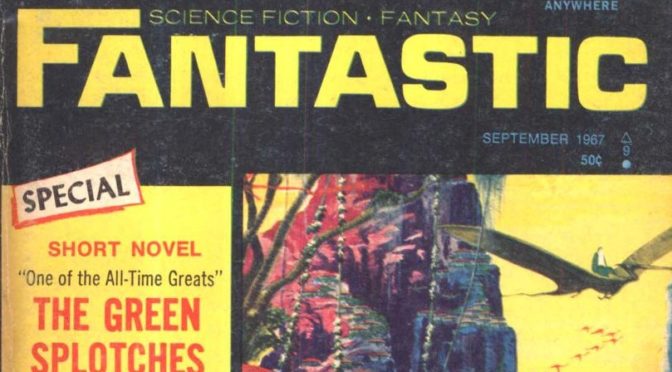

Cover art by Frank R. Paul.

As usual, the image on the front is taken from an old magazine. In this case, it's the back cover of the January 1941 issue of Amazing Stories.

The reprinted version omits the pink flamingo in the bottom right corner.

The Longest Voyage, by Richard C. Meredith

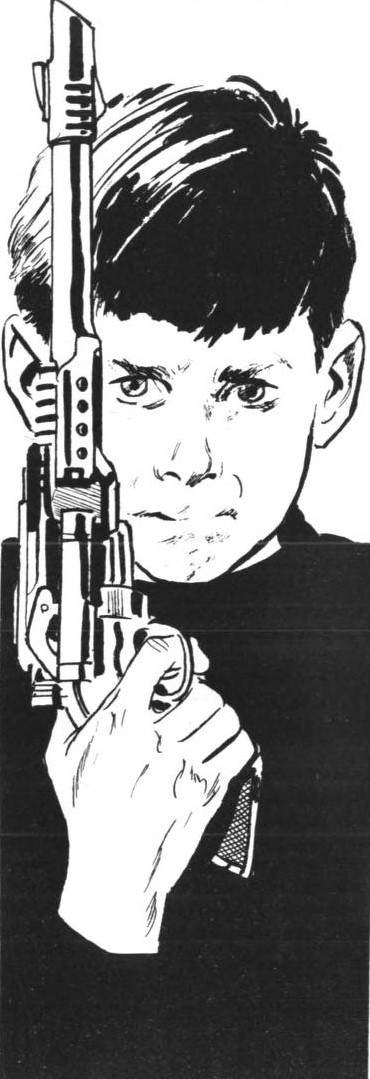

Illustrations by Gray Morrow.

Three spaceships carry the first astronauts to Jupiter. Incredibly bad luck strikes the mission. Freak accidents destroy two of the vessels and badly damage the third, leaving only one person alive. Seriously injured, the fellow faces a slow and lonely death.

It seems the crippled ship is now in orbit around Jupiter. The sole survivor has enough food, water, and air to last many years, but no way to contact Earth. (As I've indicated above, he's as far out of range as I am with KMPX.) Can our intrepid hero find a way to make his way back?

He also grows a beard.

This technological problem-solving story would be right at home in the pages of Analog. The protagonist makes use of some basic science and a lot of tinkering to overcome a seemingly impossible dilemma.

It's pretty well written for this kind of thing. The author really made me feel the character's suffering and desperation. I'm not sure I believe that a future society advanced enough to send spaceships to the far reaches of the solar system wouldn't figure out a way to talk to them. Without that plot point, the story would boil down to the hero sending out an SOS and waiting for rescue.

Three stars.

Same Autumn in a Different Park, by Peter Tate

Illustration also by Gray Morrow; he seems to be the only artist doing new work for the magazine.

Remarkably, this issue actually has two new stories. This one comes from a Welsh author usually seen in New Worlds. As you might expect, it has more than a little flavor of New Wave SF to it.

In another example of limited communication, a mother and father only talk to each other via teletype. In this grim future, the authorities have decided that the way to prevent violence is to have children raised apart from their parents. For that matter, the boy and girl in the story don't have any contact with anyone except each other and the machines that watch over them.

The devices give the children dolls representing the victims of nuclear war and a sample weapon, in an attempt to warn them about the horrors of violence. It's no surprise that this idea doesn't work out very well.

Typical of the New Wave, this story isn't as clear or linear as I may have made it sound. You have to read carefully and be patient to understand it. The premise is more effective as dark satire than as plausible speculation.

There's a strange scene in which the girl turns into a bird made from a hedge, through some kind of technological miracle. This weird transformation doesn't seem to have anything to do with the rest of the story, unless I'm missing something. It's a striking image, anyway.

This is an intriguing work, but one more to be admired than loved, I believe.

Three stars.

The Green Splotches, by T. S. Stribling

From the January 3, 1920 issue of Adventure comes this early example of interplanetary science fiction.

I'm guessing the cover artist's name is H. Tidlie, but maybe somebody with sharper eyes can make out the signature better than I can.

It was reprinted in the March 1927 issue of Amazing Stories.

Cover art by Frank R. Paul, of course.

The magazine is careful to tell me twice that Stribling went on to win a Pulitzer Prize after he lifted himself out of the pulps. For the record, it was for his 1932 work The Store, a novel about the southern United States after the time of Reconstruction.

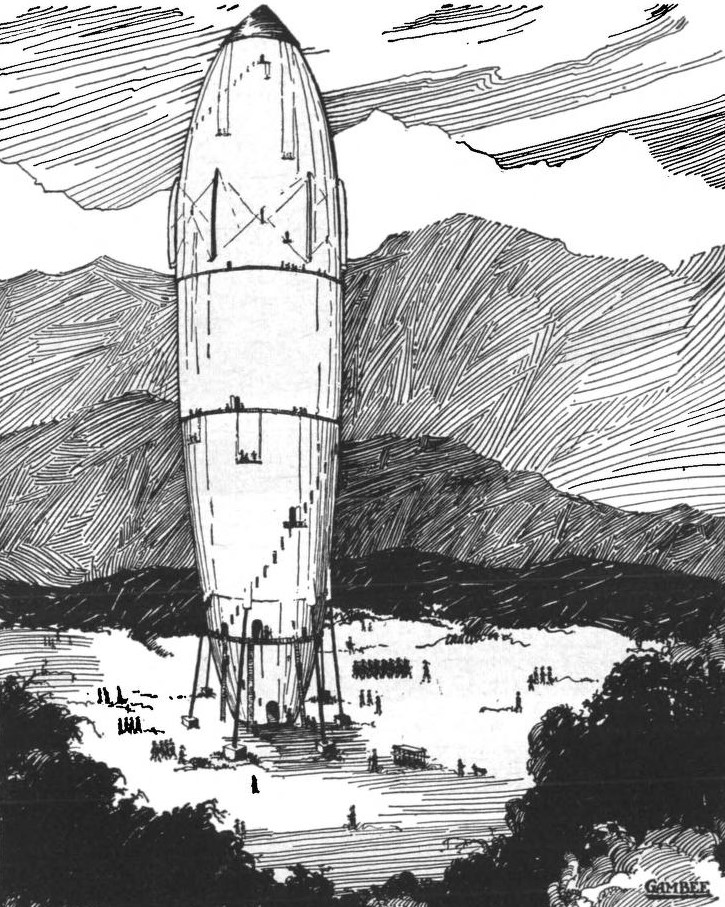

Illustration by somebody called Gambee, about whom I have no other information.

A scientific expedition heads for a remote area of Peru. The place has a very bad reputation. So much so, in fact, that the only locals willing to guide them there are two condemned criminals who would otherwise face execution.

The first eerie sign that something strange is going on comes when they find a series of carefully articulated skeletons of various animals, including a human being. Pretty soon, one of the two criminals shoots at and chases after somebody, disappearing in the process.

The others receive a visit from a strange person, who treats them as inferior beings. You'll figure things out, from the illustration if nothing else, although the human characters never do.

Although it's a little old-fashioned (this is one of those stories where radium is pretty much a synonym for magic), this is a very readable yarn. What most distinguishes it is a subtle note of satire. Although not comic, and sometimes even horrific, there's a sardonic tone throughout. There's a running joke, of sorts, about the expedition's reporter and his self-published book about reindeer.

Three stars.

The Ivy War, by David H. Keller, M.D.

The May 1930 issue of Amazing Stories supplies this Kelleryarn.

Cover art by Leo Morey.

An aggressive, swift-moving, deadly form of ivy emerges from a pit and overwhelms a small town. Soon the seemingly intelligent plant invades larger cities, moving from place to place via water. Can anything stop it?

Illustration by Leo Morey also.

This reads like a science fiction monster movie of the last decade, with ivy taking the place of a giant bug or some such. It's even got one of those endings where Science discovers the only thing that will stop the menace. There's not much to it other than the premise. For what it is, it's adequate.

Three stars.

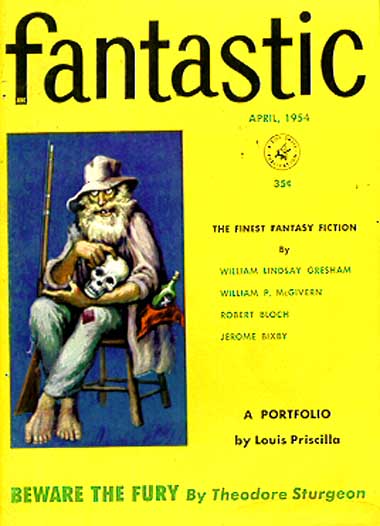

Beware the Fury, by Theodore Sturgeon

From the April 1954 issue of the magazine comes this work from one of the masters of imaginative fiction.

Cover art by Augusto Marin.

An astronaut seems to have betrayed Earth to invading aliens, making him the most hated human being in existence. A military type has the unenviable task of interviewing the traitor's wife, in an attempt to understand his actions. He learns of the man's unusual personality quirks, and of the couple's very strange marriage. With this knowledge, he tracks down the fellow when he returns to Earth and goes into hiding.

Illustration by Louis Priscilla.

I may have made this sound like a space war yarn, and there's certainly that aspect to the plot. However, the psychology of the characters is of much greater importance than the melodramatic aspects of the story. Sturgeon excels at this sort of thing, of course.

Four stars.

No Charge for Alterations, by H. L. Gold

The former editor of Galaxy offers this work from the April/May 1953 issue of Amazing Stories.

Cover art by Barye Phillips.

A doctor arrives on a colony world to study under a local physician. Medical technology exists that can change the patient not only physically, but mentally.

Interior illustrations by Henry Sharp.

He's shocked to see his mentor use the device to alter the mind of a young woman so she'll give up her dream of moving to Earth and becoming an entertainer, and instead be happy to do farm labor and raise children.

The After, in contrast to the above Before.

The new arrival decides to escape what he sees as an insane perversion of medicine and go back to Earth. The local doctor contacts the retired physician under whom he studied, in an attempt to keep the new guy from leaving. He learns something about his own time as a student.

I suppose this is supposed to be an ironic tale, maybe even humorous. I found the premise distasteful. The way in which the young woman at the start of the story is brainwashed to be a content farm wife is rationalized as being necessary to support the colony, but it gave me the creeps.

Two stars.

Signal to Noise Ratio

Well, that was a middle-of-the-road issue, rising above and sinking below average in a couple of places, but otherwise mediocre. It's notable not only for having two new stories, but for having only science fiction and no fantasy. The whole thing is like a radio station subject to bits of static now and then; worth tuning in for a while, but tempting you to turn the dial to something else. Something like a corny pun, that may amuse you for a while, but otherwise forgettable.

Like this one, from the same issue as the Sturgeon story, by somebody known only as Frosty.

Still, while I may not be able to tune in to KMPX, I can at least turn the dial to the similarly formatted KGJ. That's some comfort!

"The Longest Voyage" was good for what it is, though as you say the difficulty of communicating with civilization was fairly silly. Meredith seems to have a bee in his bonnet about dying well or at the very least not going gentle into that good night.

I didn't much care for the Tate. It does demand careful and patient reading, but the reward wasn't worth it for me. Maybe if he'd used a different format for the parental communication. I found it difficult to read and tended to skim, which probably diminished its effect.

Though he wrote not a few adventure yarns, Stribling garnered attention and his Pulitzer covering much the same ground as Faulkner, though not as well. On the other hand, he wasn't afraid to tackle the issue of race in the South and did so with a favorable attitude toward his Black characters (even if it may not necessarily seem that way 30 or 40 years later.) This was a decent adventure, if not quite up to today's standards.

"The Ivy War" was also very much of its day. It also made me think of Ward Moore's "Greener Than You Think," which is this with crabgrass by way of John Wyndham and much better.

I do wish Sturgeon would return to his typewriter. He is so very, very good. This reminded me of a story from a couple of years ago about a fellow in a similar situation, but on trial for his actions. It might have been by Mack Reynolds, but I won't swear to that.

The Gold was deeply unpleasant. The ethics of the situation are completely unacceptable.