by Gideon Marcus

SFlying Eastward

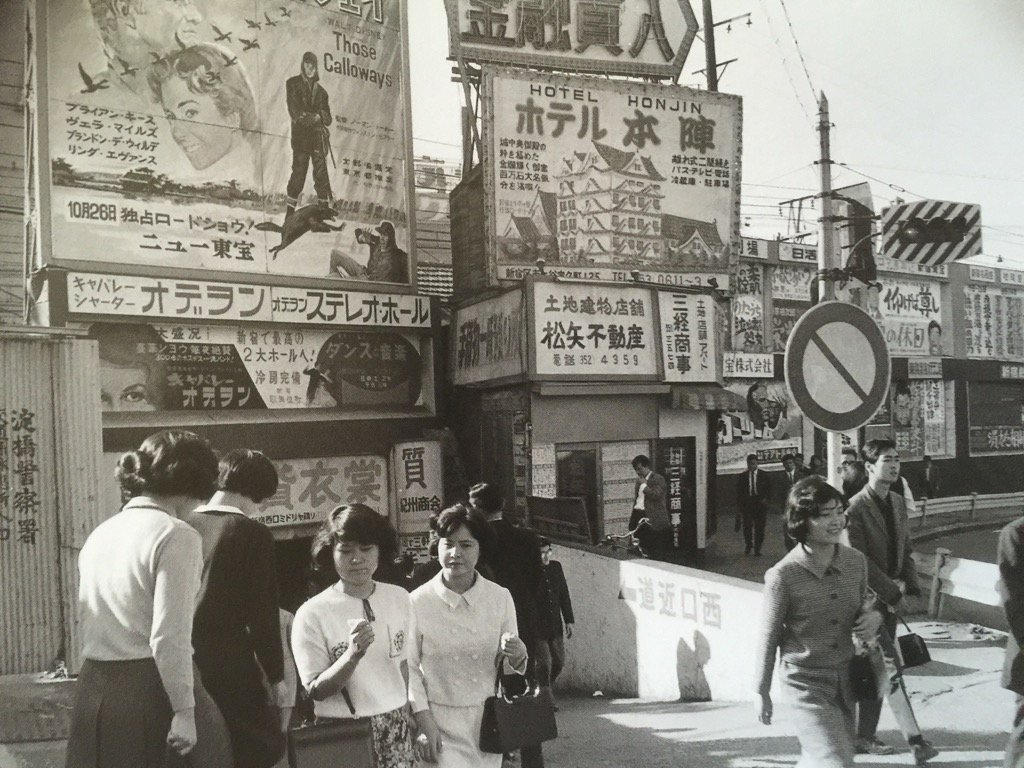

Today saw the Journey in the wilds of Utah, attending a small science fiction conclave out in the lovely summer desert of Deseret. What could have impelled us to make another plane trek less than a week after having returned from a long sojourn in Japan?

Well, we were invited. The things one does for egoboo…

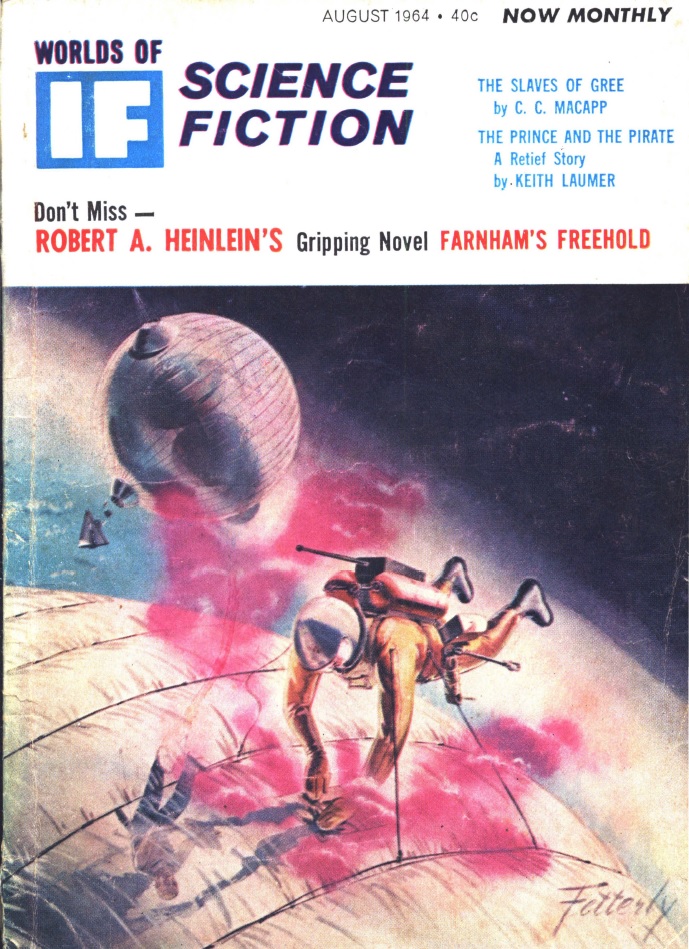

Nevertheless, duty continues, and so I find myself pounding the typewriter keys early in the morning (to the chagrin of the folks in the neighboring rooms, no doubt) so you can read all about the first SF digest of the month, the August 1964 IF.

The Issue at Hand

by Fetterly

The big news is that IF is a monthly now after years and years as a bimonthly. Lord knows where editor Fred Pohl is getting the material for this increased frequency, especially given that he also helms the sister books, Galaxy and Worlds of Tomorrow. Let's see how the new mag holds up under the compressed schedule:

The Slaves of Gree, by C. C. MacApp

by Gray Morrow

Young Jen wakes up spluttering in a pounding sea, his memories forgotten, with the trace of a foreign name in the back of his mind. Who is "Steve Duke" and what is his relation to Jen? The hapless jetsam of a man is rescued by his own kind, fellow slaves to the great Gree. Jen soon gets back his memories, remembering that he belongs to the happy, harmonious Hive, a burgeoning galactic power.

Or does he?

Turns out Jen is a double-agent, quite literally. He has two personalities, which swap as needed. One is one of the Hive's most promising subalterns, a puissant veteran of the space corps. The other is Major Steve Duke, a rather unsavory Terran sent to topple the Hive from within.

There are the makings of a great story here, but it needs a lot of polish. So much of the tale is told mechanically. At one point, I counted ten sentences in a row beginning with "He [verbed]…" Plus, I kept expecting a twist at the end, but instead, it's just a straight adventure story with (I felt) the wrong personality winning.

Two stars, just shy of three.

A as in Android, by Frances T. Hall

A middle aged rebel against the system encounters an android with his face and imprinted with his memories – memories he'd sold for some quick cash a decade and a half before. Has the robot, who was exiled to the hell planet called Cauldron, come for revenge or something else?

Frances Hall's first SF story (to my knowledge) is a solid triple. Four stars.

The Prince and the Pirate, by Keith Laumer

by Nodel

The latest Retief story sees our favorite interstellar diplomat/super spy thwarting the topple of a monarchy. Neither the best nor the worst of the stories in the series, it entertains reasonably. Three stars.

The Life Hater, by Fred Saberhagen

How do you convince a machine that biological life is superior? And in the parley between human and sentient, life-hating battleship, who is playing who?

Fred Saberhagen continues to impress with his excellent tales of the Berserkers — sentient dreadnoughts who scour the galaxy, ridding it of biological infestations.

Four stars.

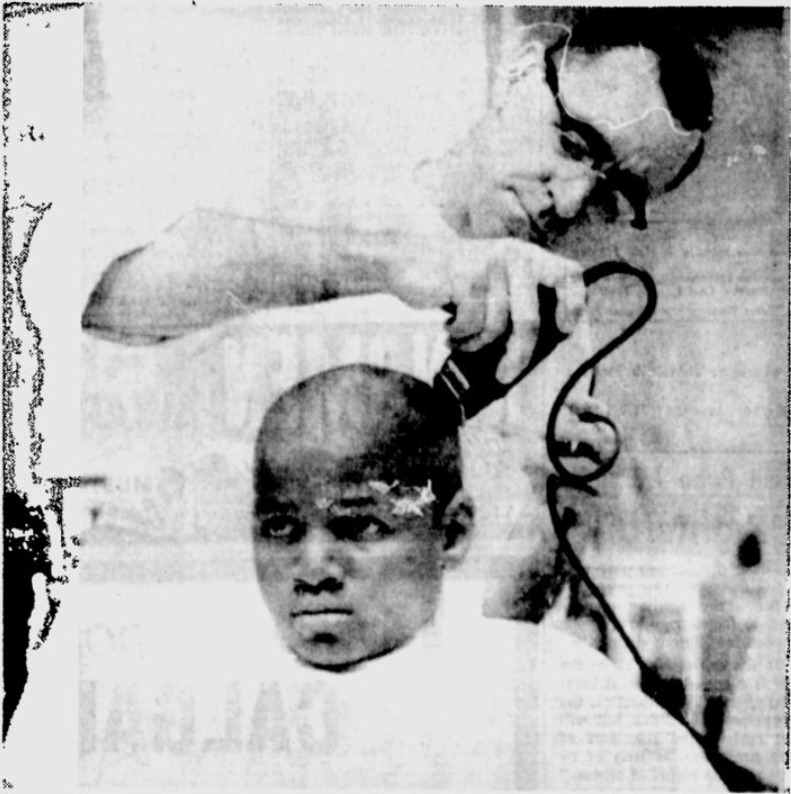

Farnham's Freehold (Part 2 of 3), by Robert A. Heinlein

by Jack Gaughan

Last up is the latest installment of Heinlein's most recent novel. Last time, Hugh Farnham, a libertarian, nudist cat-lover (no resemblance whatsoever to his creator!) ducked into a bomb shelter with his family when the Russkies started to nuke America. Instead of dying in the holocaust, however, Farnham et. al. found themselves transported to a virgin version of their world, one in which people had never existed. Or so they thought.

At the beginning of this month's narrative, other people show up — technologically advanced black men who enslave the Farnhams (except for their house servant, Joe, who is black) and bring them to the Summer Palace of Ponse, Lord Protector of the region. It turns out that this isn't an alternate universe, but rather some two thousand years in the future. Descendants of the Africans now rule the world in a static society in which the whites are slaves. Hugh must use his wits to carve a place for himself in this society before he is eliminated (or worse!) for trespassing.

This second part holds up a lot better than the first. Near the end, we learn that there are still free savages hiding in the Rocky Mountains, an Part 3 will likely feature some kind of Farnhem-led insurrection. All very patriotic and appropriate for Independence Day.

Four stars.

Summing Up

Truth to tell, I'd been dreading the Heinlein and leery of the rest of the issue. In the end, though, Pohl managed to put together a readable (if not stellar) 132 pages of SF. I will definitely be keeping my subscription!

Let's just hope that he…and I… can keep up this busy schedule.

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

![[July 6, 1964] Busy Schedule (August 1964 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/640706cover-672x372.jpg)

![[July 4, 1964] A Struggle for Freedom (The Civil Rights Act)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/640704jobmarch-672x372.jpg)

![[July 2, 1964] Completing the Tour (July 1964 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/640702cover-672x372.jpg)

![[June 30, 1964] A big Delta (June 1964 <i>Gamma</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/640630cover-453x372.jpg)

![[June 28, 1964] Not Quite What You Think. ( <i>New Worlds, July-August 1964</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/640628cover-563x372.jpg)

![[June 26, 1964] Curtain Call (<i>Twilight Zone</i>, Season 5, Episodes 33-36)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/640624c-672x372.jpg)

![[June 24, 1964] Death Has No Master (Roger Corman's <i>The Masque of the Red Death</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/masqueposter-672x372.jpg)

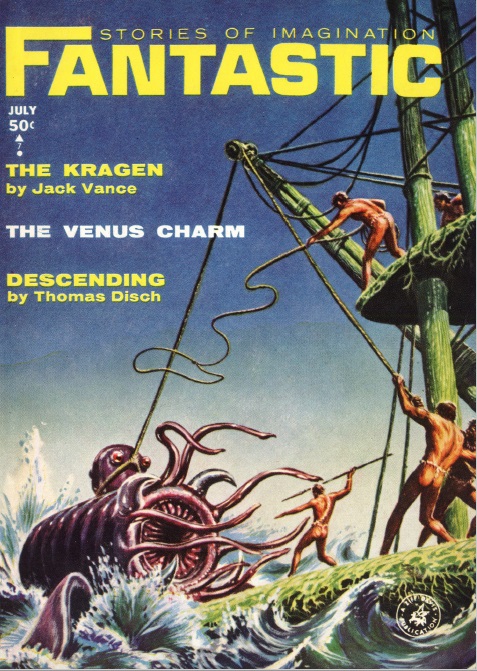

![[June 22, 1964] The Bridal Path (July 1964 <i>Fantastic</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/640622cover-477x372.jpg)

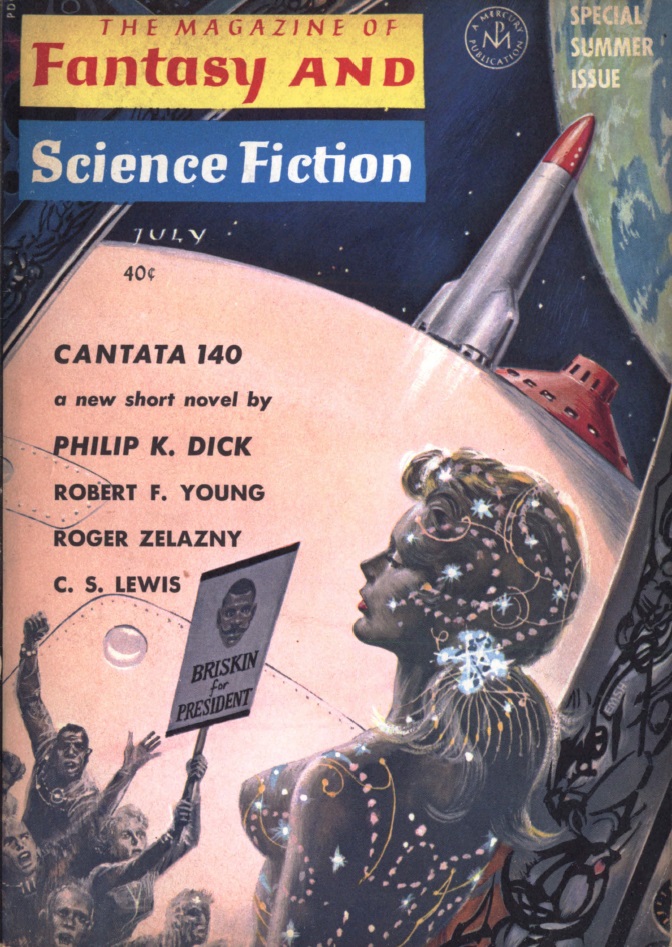

![[June 20, 1964] How low can you go? (July 1964 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/640620cover-672x372.jpg)

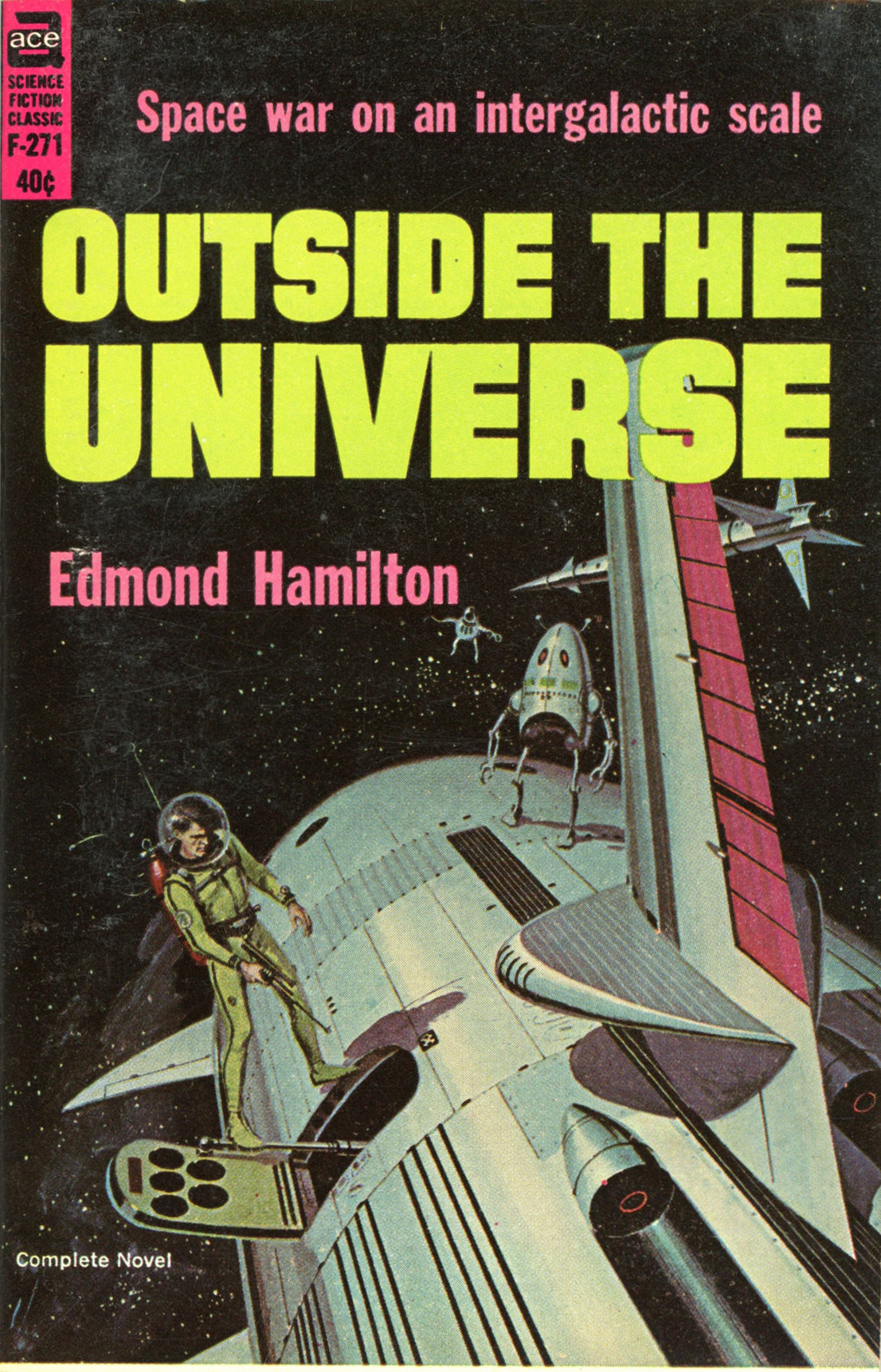

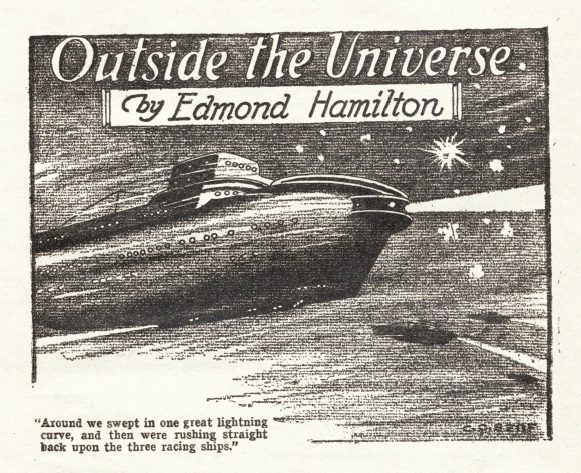

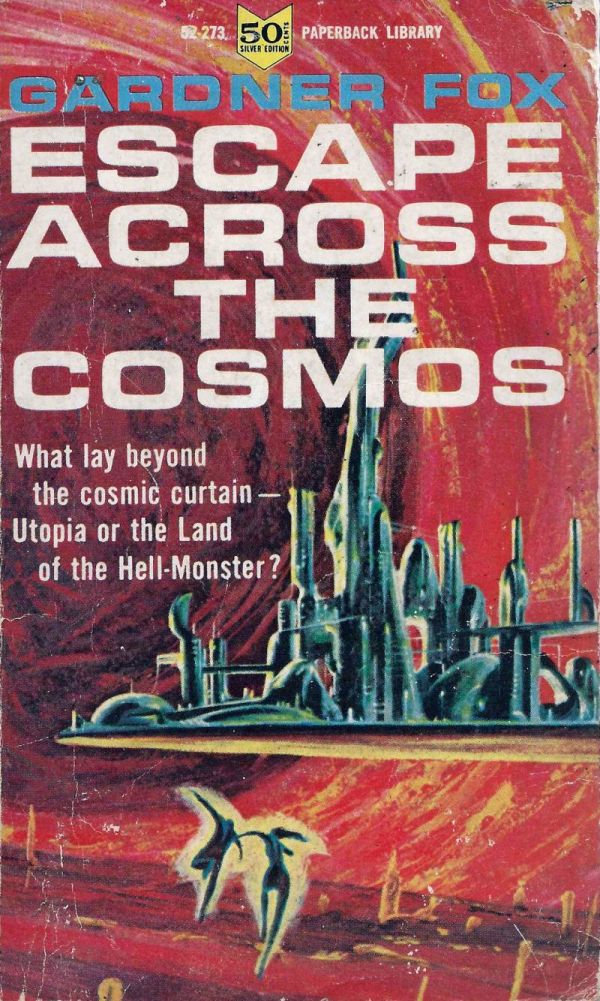

![[June 18, 1964] Bad Comic Book Style and Good Comic Book Style (Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/158064-672x372.jpg)

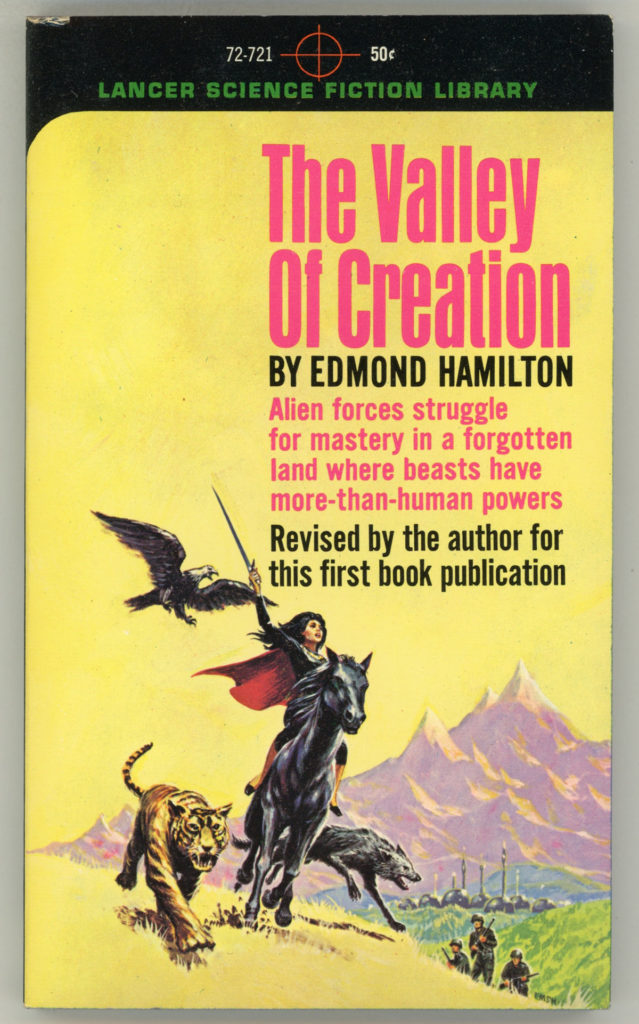

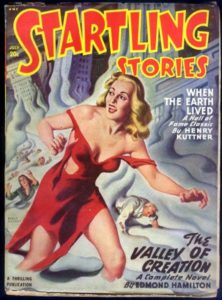

The Valley of Creation is an action-packed science fantasy adventure that feels like a throwback to the pulp era, probably because it is. For The Valley of Creation is an expanded version of a story first published in the July 1948 issue of Startling Stories. This has caused some anachronisms, e.g. at one point Eric remarks that he has been in Asia for ten years, which would set the story in 1960. However, the Chinese Civil War and the annexation of Tibet and the East Turkestan Republic, which are the reason why Eric and his comrades are in the Himalayas in the first place, happened in 1949 and 1950, i.e. shortly after the story was originally published.

The Valley of Creation is an action-packed science fantasy adventure that feels like a throwback to the pulp era, probably because it is. For The Valley of Creation is an expanded version of a story first published in the July 1948 issue of Startling Stories. This has caused some anachronisms, e.g. at one point Eric remarks that he has been in Asia for ten years, which would set the story in 1960. However, the Chinese Civil War and the annexation of Tibet and the East Turkestan Republic, which are the reason why Eric and his comrades are in the Himalayas in the first place, happened in 1949 and 1950, i.e. shortly after the story was originally published.