by Cora Buhlert

Clever Little Foxes: Fix and Foxi

Here at the Journey, we occasionally visit the wonderful world of comic books, mostly from the US but also from the UK. However, comics have long been a global phenomenon and so I'm presenting you the comics of East and West Germany.

Superheroes may rule in the US, but in West Germany, you will have a hard time finding American superhero comics, unless you have befriended an American GI who can hook you up with the latest US comics.

Instead, the most popular US comics in West Germany are none than the Disney comics featuring Donald Duck, Mickey Mouse and friends. A large part of the reason why the Disney comics are so popular in West Germany is the brilliant work of translator Erika Fuchs, who introduced inventive wordplay and allusions to classic literature into the comics and thus gained a large adult fanbase. The various linguistic "donaldisms" created by Erika Fuchs have even entered the regular German language by now.

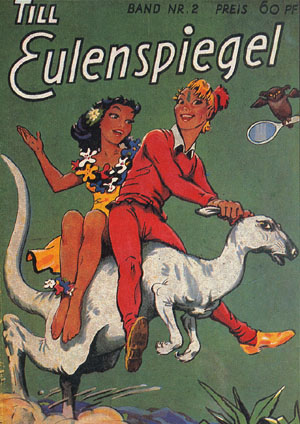

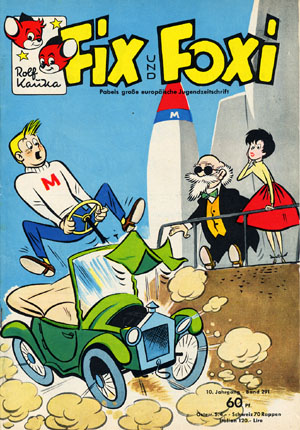

Inspired by the success of the Disney comics, in 1953 West German artist Rolf Kauka created his own comic magazine called Till Eulenspiegel, named after a popular trickster character from German legend. However, a pair of clever foxes named Fix and Foxi quickly became the most popular characters and in 1955, the magazine was retitled as Fix und Foxi. The two foxes quickly adopted a whole menagerie of animal friends such as the wolf Lupo and his cousin Lupinchen, the mole Pauli and the sister Paulinchen, the raven Knox, the hare Hops, the hedgehog Stops and the mouse Mausi. Other characters to appear in the magazine are "Tom and Klein Biberherz" (Little Beaverheart), a cowboy character and his indigenous friend, and "Mischa im Weltraum" (Mischa in Outer Space), a humorous science fiction comic. Those who have read the Archie comics will find that Mischa looks very familiar.

Mecki: The Amazing Adventures of a Little Hedgehog

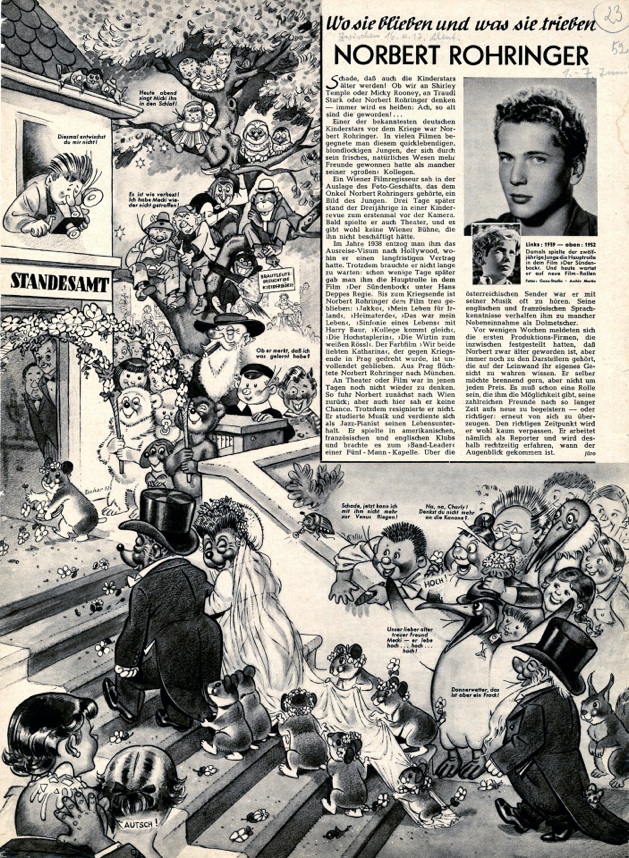

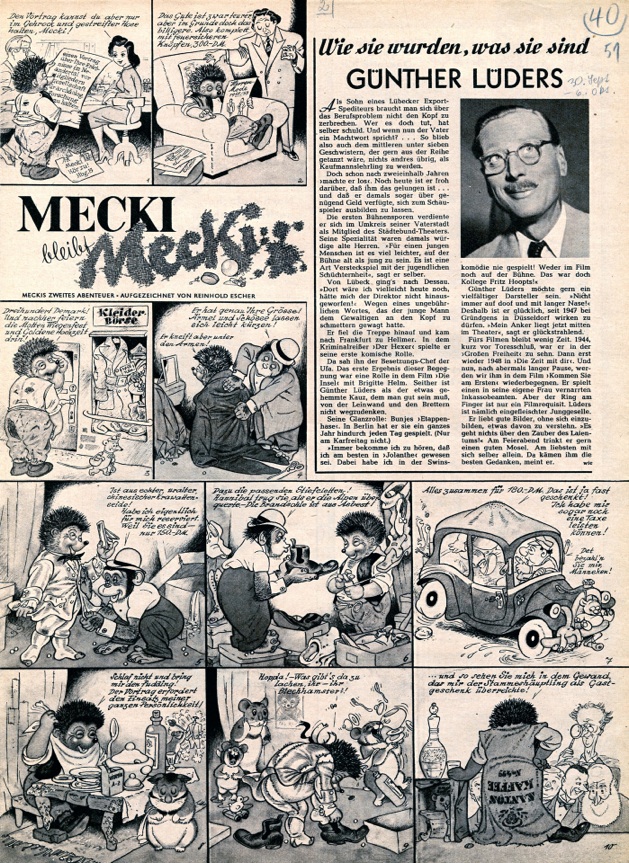

Fix and Foxi are not the only anthropomorphic animals in West German comics. There is also Mecki the hedgehog, whose tangled history predates the two foxes. Mecki first appeared in 1938 – still nameless and not in comic format at all, but in an animated puppet film adaptation of the Grimm fairy tale "The Race between Hare and Hedgehog". The film spawned a series of picture postcards featuring the clever little hedgehog.

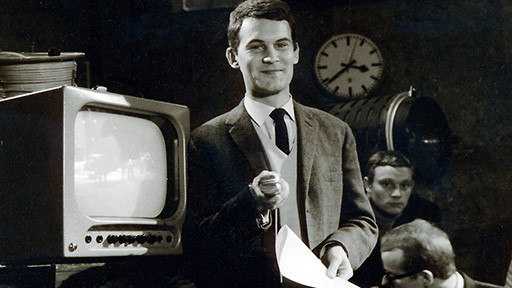

In 1949, one of those picture postcards landed on the desk of Eduard Rhein, Renaissance man (in now 65 years, Rhein has been a Zeppelin engineer, inventor, technical writer, violinist and novelist) and editor-in-chief of the radio listings magazine Hör Zu! (Listen!). Rhein was looking for a mascot for the magazine, a character who would offers snarky commentary on the program listings. He promptly adopted the hedgehog and named him Mecki. The character debuted on the cover of issue 43 of Hör Zu!, still as a puppet character in a pre-war picture postcard. When Rhein ran out of picture postcards to reprint, he recruited cartoonist Reinhold Escher to draw new adventures of the brave little hedgehog.

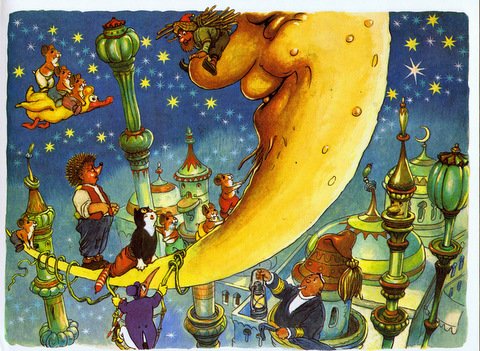

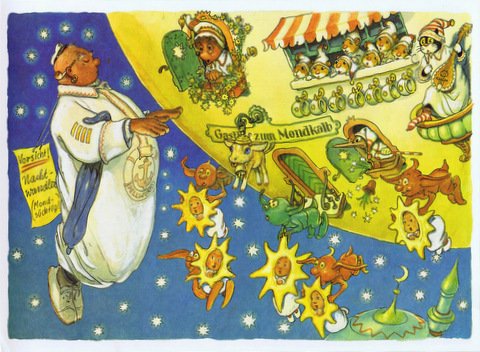

From 1951 on, one page Mecki strips appeared in Hör Zu!, initially as standalone stories and later as serialised adventures. Mecki also quickly acquired friends and family, including his wife Micki and the two children Mucki and Macki, the penguin Charly, the Schrat, a permanently sleepy gnome, the seven Syrian hamsters, the seaman Captain Petersen, the cat Murr and the duck Watsch. Together, these characters travelled the world, ventured into various fantasylands and even conquered the Moon and Mars as early as 1953.

Beginning in 1952, Mecki's adventures also appeared in full colour picture books. The first book, Mecki im Schlaraffenland (Mecki in Cockaigne) was written by Eduard Rhein and illustrated by Reinhold Escher, but from book two on, Wilhelm Petersen illustrated the Mecki books and later also shared artist duties with Reinhold Escher on the comic strip. Reinhold Escher's style is more cartoony, while Petersen's is more naturalistic, but both of them are highly talented artists. As a result the Mecki strips and particularly the picture books look gorgeous.

Mecki and his extended family eventually returned to the medium that birthed him for a series of eighteen short puppet movies. The toy manufacturer Steiff also produces dolls of Mecki and his family. I got the complete set of Mecki, Micki, Macki and Mucki as a birthday gift some time ago and treasure them.

In spite of Mecki's popularity, his future is uncertain, for his creator Eduard Rhein left Hör Zu! last year – not voluntarily, it is rumoured. And Rhein's replacement shows little interest in Mecki. The comic strips continue to appear in Hör Zu!, but the annual picture book has been cancelled. Nonetheless, I hope that the friendly little hedgehog and his friends will continue to delight readers for a long time to come.

In the News: Nick Knatterton and Bild Lilli

Daily comic strips can be found in many West German newspapers. However, most of these are reprints of American comic strips such as The Phantom, Blondie or The Heart of Juliet Jones. Homegrown German comic strips are rare.

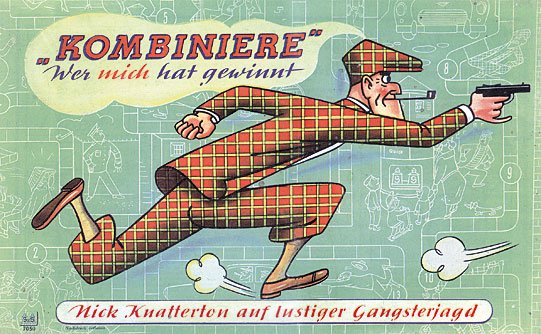

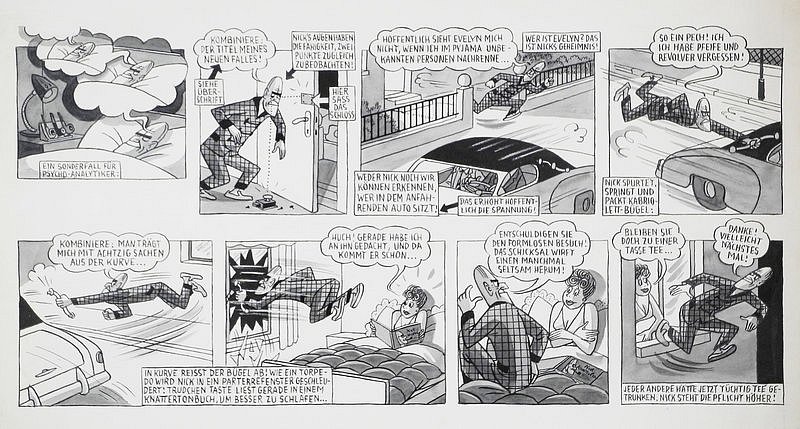

One exception is the square-jawed private detective Nick Knatterton, whose adventures appeared between 1950 and 1959 in the magazine Quick.

Nick Knatterton's real name is Nikolaus Kuno Baron von Knatter. His mother Baroness von Knatter was an eager reader of murder mysteries. Inspired by her, Nick Knatterton decided to become a private detective and changed his name, so as not to embarrass his aristocratic family. Knatterton was a confirmed bachelor for many years, until he met and eventually married the heiress Linda Knips.

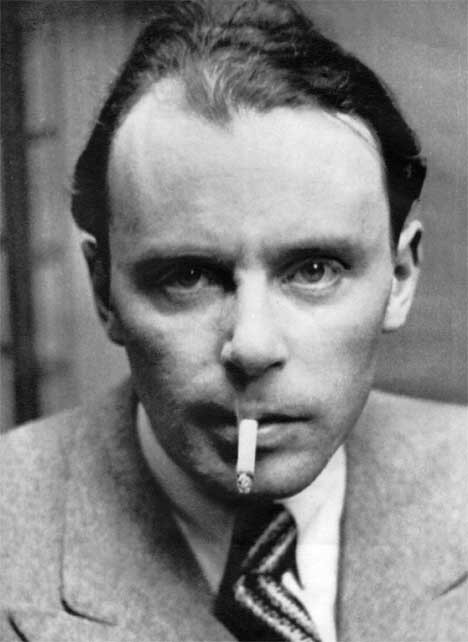

Nick Knatterton was created by Manfred Schmidt, a cartoonist who hails from my hometown of Bremen. Shortly after World War II, Schmidt came across a Superman comic. Inspired by this new to him medium, he created Nick Knatterton. Other inspirations for the character were Sherlock Holmes as portrayed by Hans Albers in the 1937 movie Der Mann der Sherlock Holmes war (The Man Who Was Sherlock Holmes) as well as the American dime novel hero Nat Pinkerton, whose adventures a young Manfred Schmidt had devoured in the 1920s.

What makes the Knatterton comics so amusing are not just Schmidt's crisp drawings, but also the political satire that Schmidt, who considers himself a Communist, inserts into the strip.

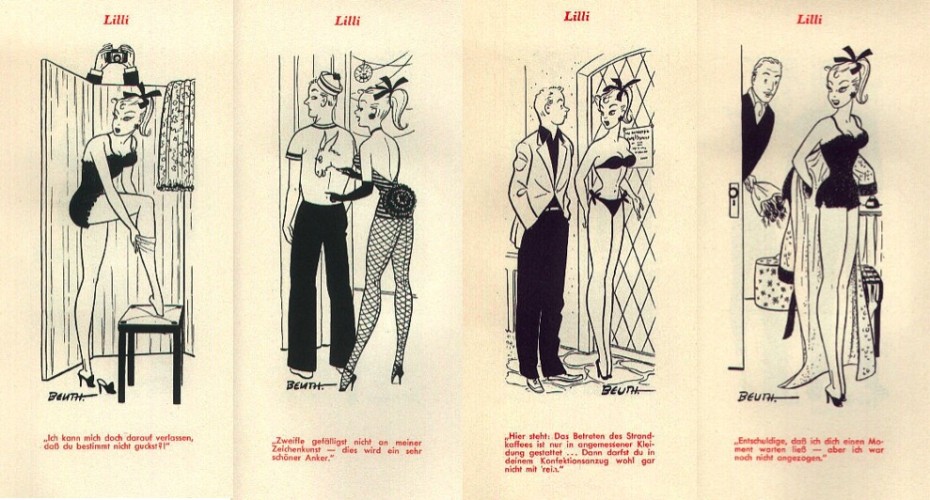

Whereas Nick Knatterton is very political, Bild Lilli, another homegrown West German comic strip character, is not overly political at all. Created by cartoonist Reinhard Beuthien for the tabloid Bild, the attractive Lilli is a ditzy young woman who works as a secretary, but dreams of catching a wealthy husband. The mildly risqué Lilli strip was popular enough to spawn a Lilli fashion doll and a line of matching outfits. But sexist humour fell out of favour and so the strip was cancelled in 1961.

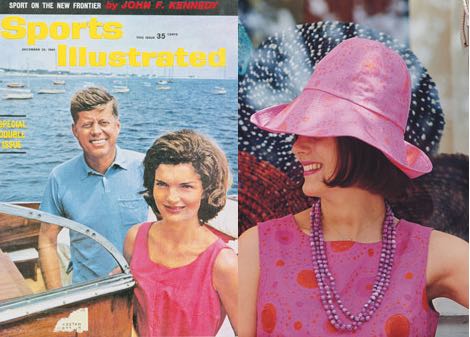

This could have been the end of Lilli, but instead she continued her career under a different name. For in 1958, an American tourist named Ruth Handler purchased a Bild Lilli doll and was so impressed by the idea of a fashion doll that she created her own version. Named Barbie after Mrs. Handler's daughter, this doll became a huge worldwide hit.

Heroes to Carry in Your Pocket: Sigurd, Falk, Tibor, Jörg and Nick

One of West Germany's foremost comic publishers is the Walter Lehning Verlag, which started publishing comics in 1953, beginning with reprints of Italian series such as the jungle hero Akim and the western hero El Bravo. Those had been originally published in the so-called piccolo format, small and wide booklets in horizontal format that look like individual newspaper strips stapled together, so the German editions used the same format.

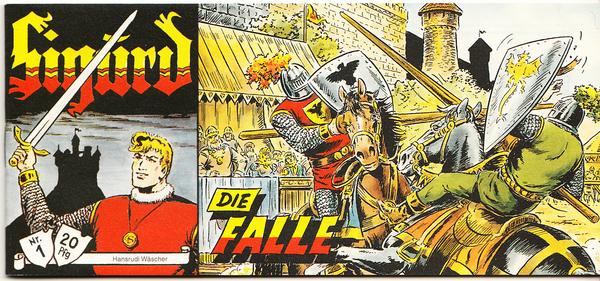

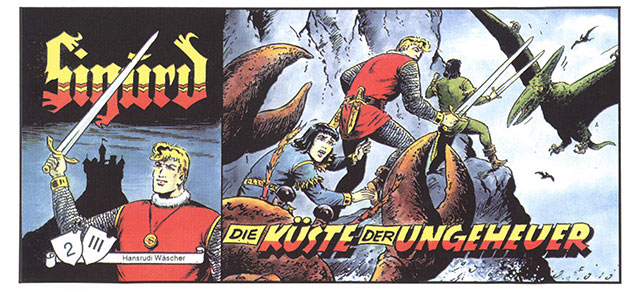

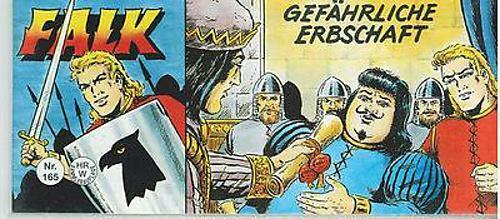

The advantage of the piccolo format was that at twenty pfennig apiece, the comics were cheaper than those published in regular magazine format. As a result, the reprints of Italian action comics were so popular that Lehning commissioned Swiss German artist and writer Hansrudi Wäscher to create several new series in the same format.

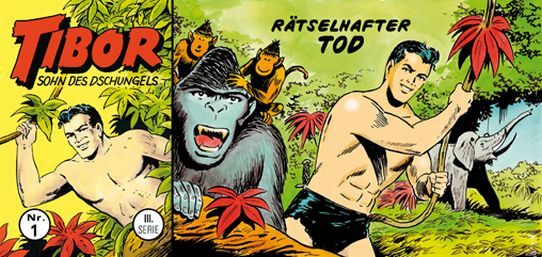

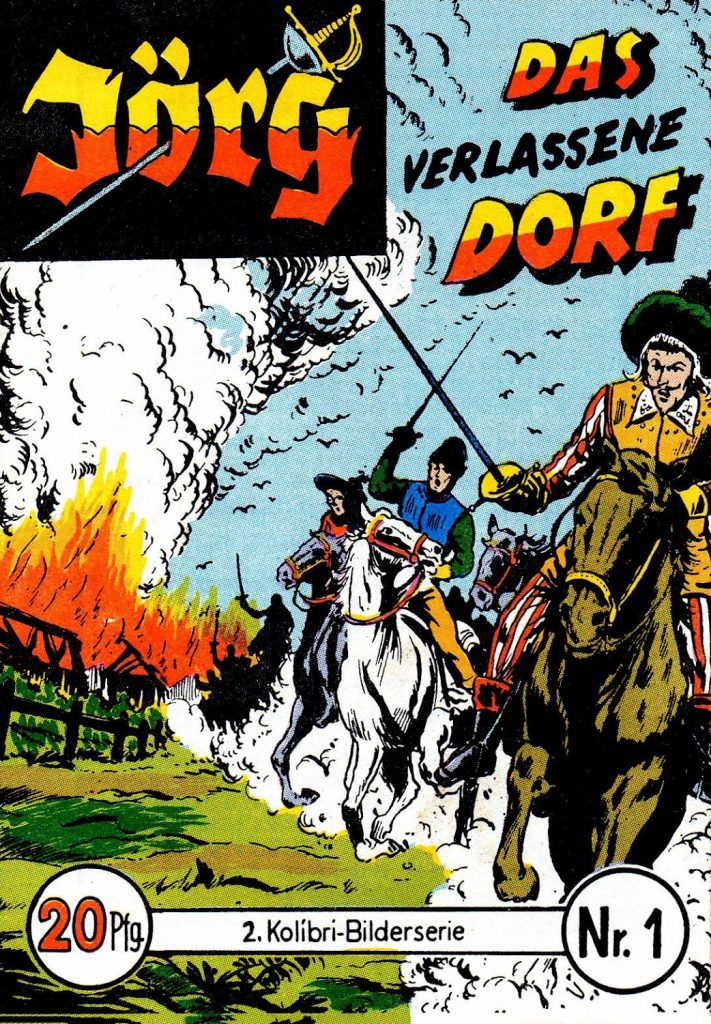

Wäscher's first creation for Lehning was Sigurd, a medieval knight who had more than three hundred adventures between 1953 and 1960. Sigurd was a big success and was quickly followed by Falk, another knightly hero, Tibor, a jungle hero in the mould of Tarzan who was created as a replacement for the Italian Akim character, Jörg, a young nobleman who experiences adventures during the thirty-years-war, and Nick, der Weltraumfahrer (Nick the Spaceman), a science fiction comic.

However, the prolific Hansrudi Wäscher also worked for other comic publishers. He created Nizar, yet another jungle hero, for the publisher Kölling Verlag as well as Titanus, a science fiction comic, for the Gerstmayer Verlag. The Titanus comics had a special gimmick, because they came with 3D goggles.

Adventures Behind the Iron Curtain: Mosaik

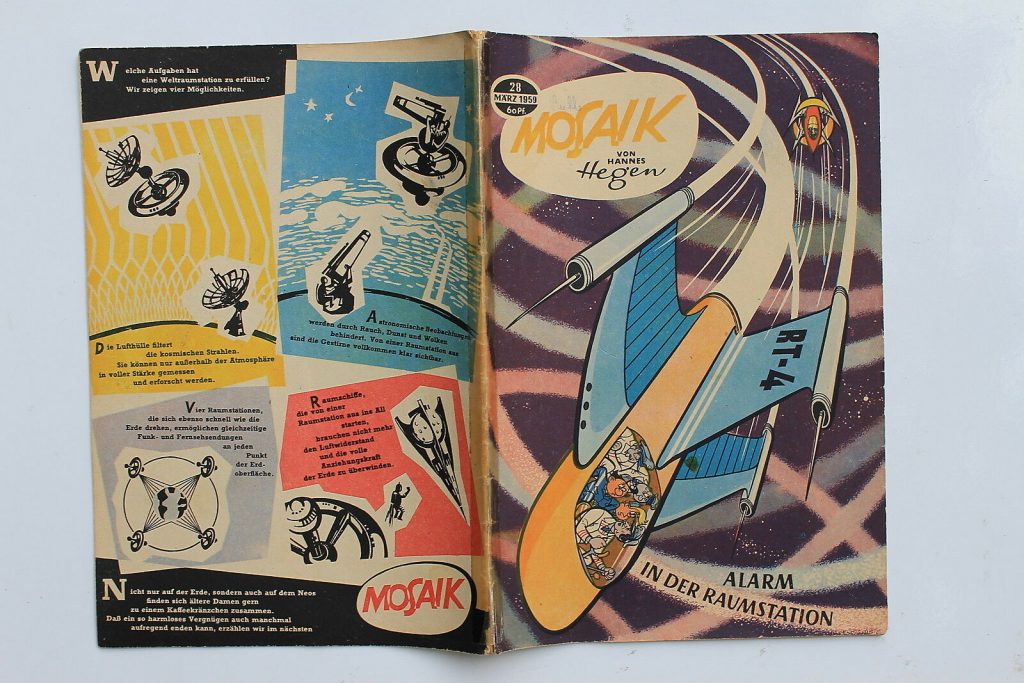

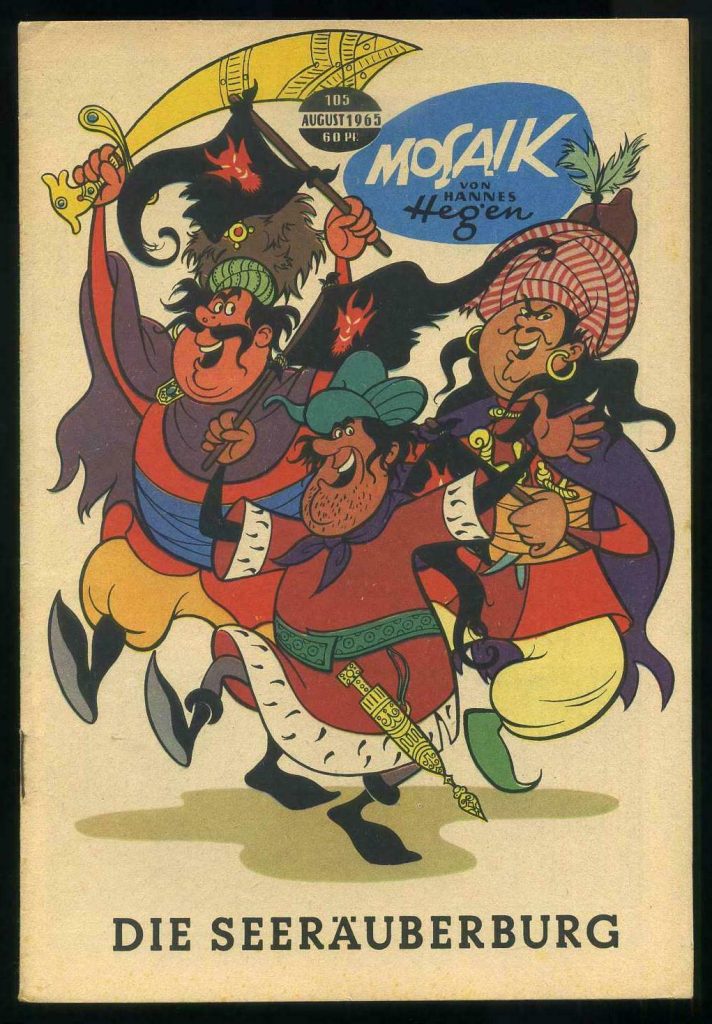

Western comic books also found their way across the iron curtain, to the delight of East German youths and the despair of the Communist authorities. And so in 1955, the East German publisher Verlag Neues Leben created their own comics magazine called Mosaik. Initially, the magazine appeared quarterly and switched to a monthly schedule in 1957. Due to the vagaries of Socialist paper production, Mosaik issues are not easy to find on the newsstands of East Germany and always sell out quickly, unless you know someone who will reserve a copy for you.

The stars of Mosaik are three cobolds named Dig, Dag and Digedag. The Digedags, as they are collectively known, have amazing adventures in time and space. So far, they have fought pirates, founded a circus, travelled to ancient Rome and into outer space and meet various important historical figures. Their latest adventure has taken them to the Middle Ages, where they picked up a new travelling companion in the clumsy knight Ritter Runkel.

So how Socialist are the Digedags? The answer is, "It's complicated." During their epic space adventure, the Digedags were dragged into a conflict between the Republican Union, a Socialist utopia, and their sworn enemies, the Großneonian Reich, an expansionist capitalist hell state ruled by people dressed in what looks like SS uniforms. But while the space saga wore its Socialist heart on its sleeve, the following inventor cycle was the opposite. For the inspirational inventors from history the Digedags encountered include not just East German hero Otto von Guericke, 17th century scientist and mayor of Magdeburg, but also capitalists such as James Watt and even Werner von Siemens, aristocrat and capitalist, whom the Digedags meet as a young lieutenant in the Prussian army.

However, the main objective of Mosaik is apolitical fun, which is also why the magazine is so much more popular than other publications from the same company such as Die Trommel (The Drum), the official magazine of the Ernst Thälmann Young Pioneers, which includes such thrilling comic strips as "The Girl from the Soviet War Monument" or "The Red Climbers".

The Digedags were the creation of cartoonist Hannes Hegen, but in true Socialist fashion the comic is created by a collective of writers and artists. The current head writer is Lothar Dräger. The main artist is Lona Rietschel, one of the few women to work in German comics.

And that's it for the comics of East and West Germany. Next month, I will introduce you to the comics of Belgium, France and the Netherlands.

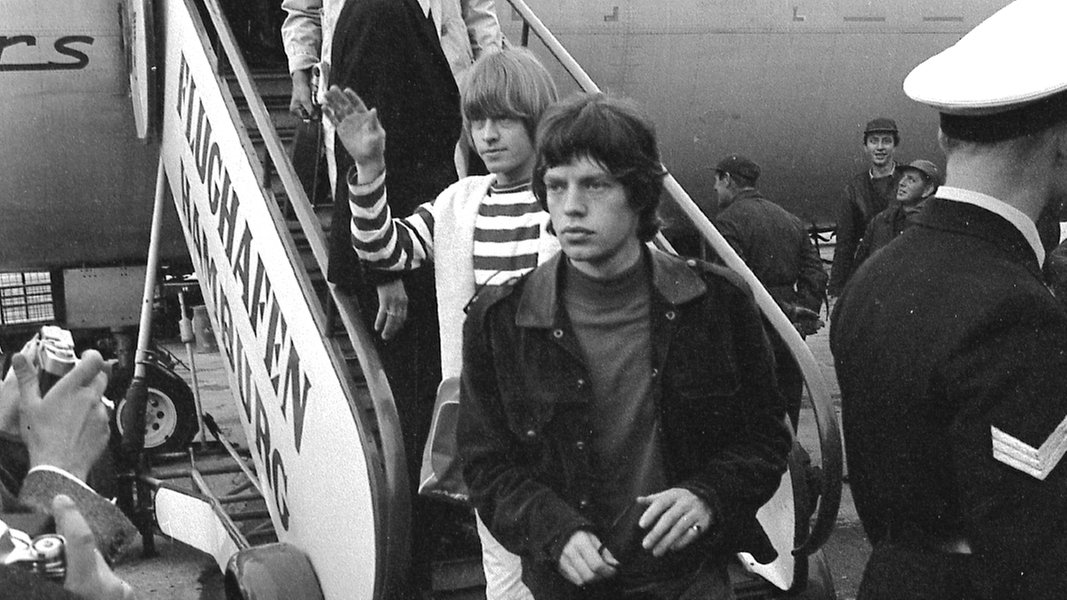

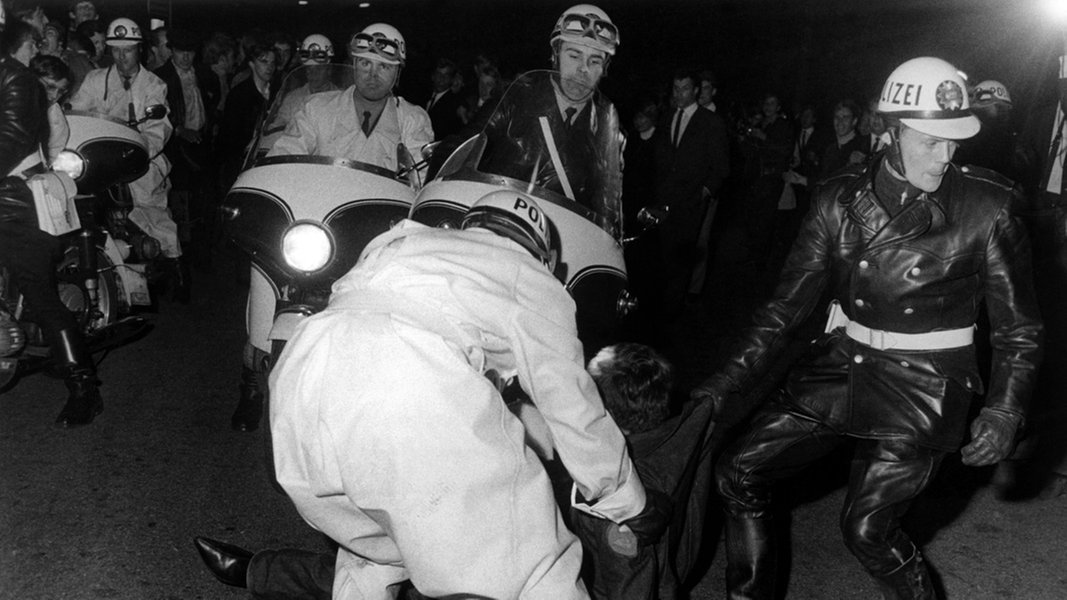

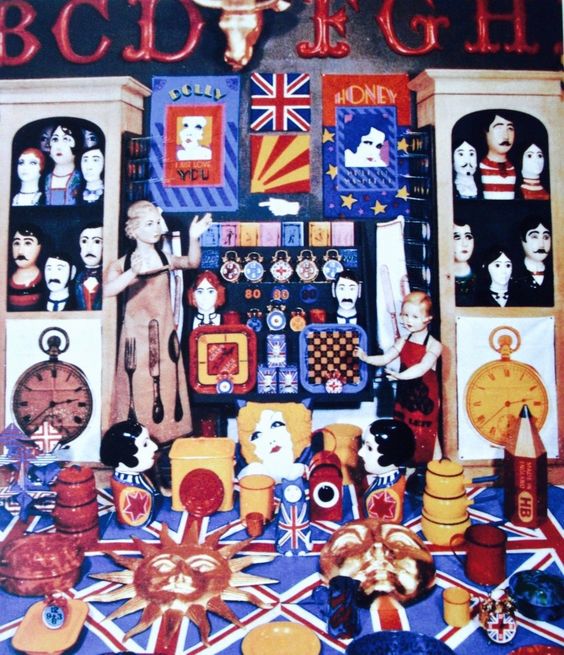

![[September 28, 1965] Of Art and Freedom: The Rolling Stones Riots and the <i>Mephisto</i> Case](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/1018-672x372.jpg)

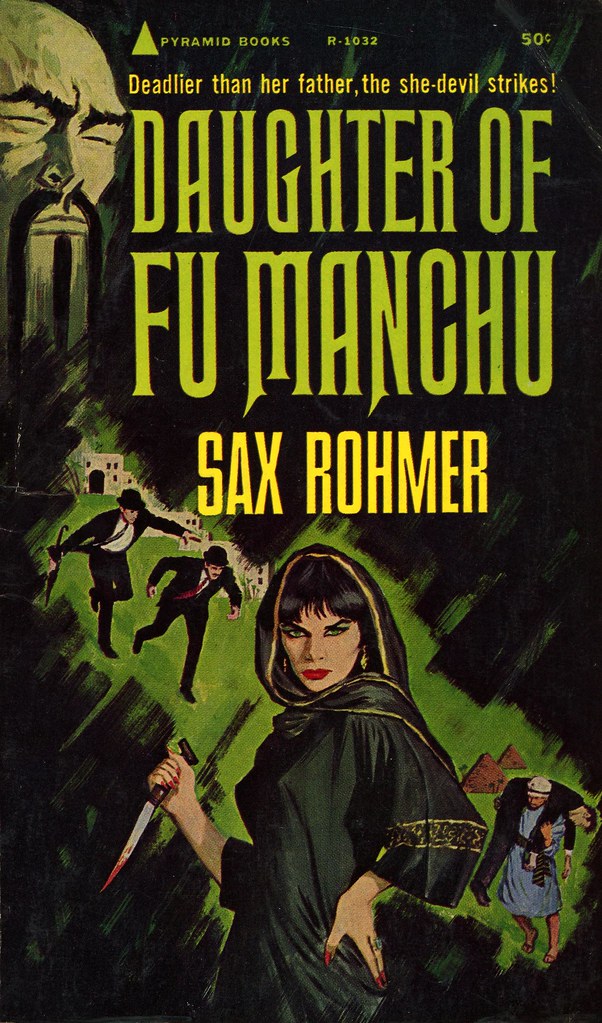

![[August 14, 1965]: A Killer Thriller Double-Feature: <i>Again the Ringer</i> and <i>The Face of Fu Manchu</i>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/MV5BOGM3MTE1MTktYzJlZS00MTkwLTlhMWQtNWU4NzYwZWE5Mzk5L2ltYWdlL2ltYWdlXkEyXkFqcGdeQXVyMjI4MjA5MzA@._V1_-578x372.jpg)

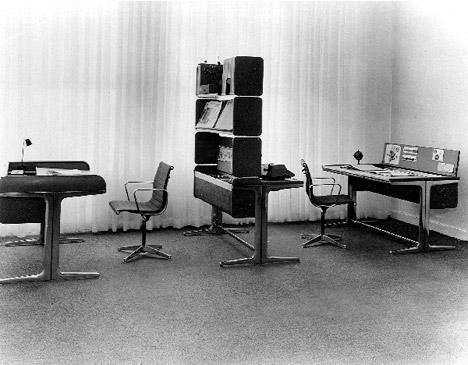

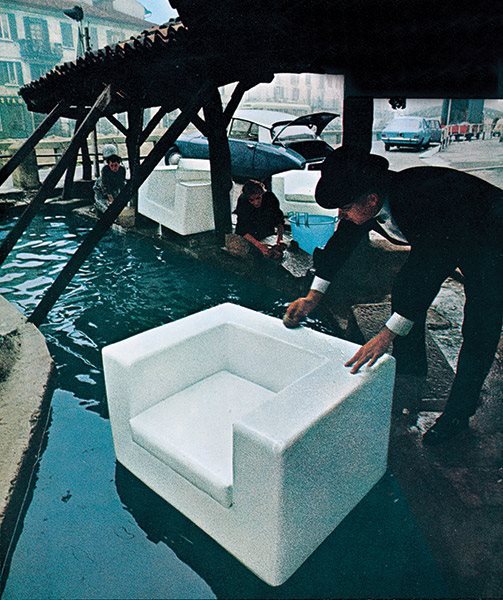

![[April 10, 1965] Furnishing the Home of the Future: Interior Design for the Space Age](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/39340889-672x372.jpg)

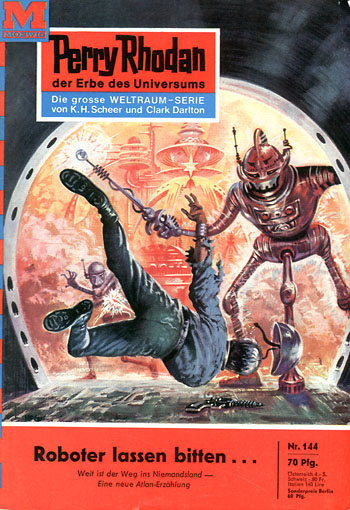

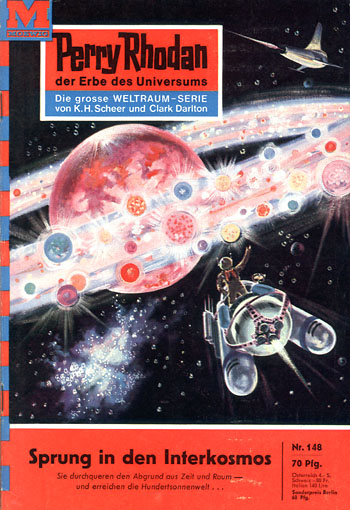

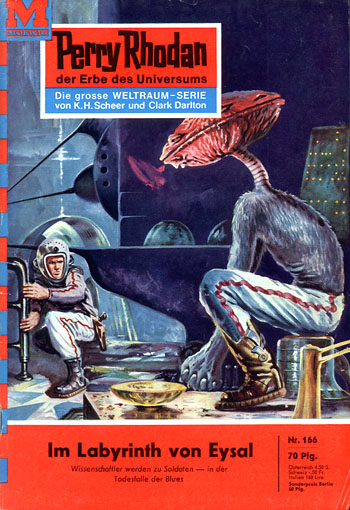

![[November 5, 1964] The State of the Solar Empire: <i>Perry Rhodan</i> in 1964](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/PR0107-350x372.jpg)

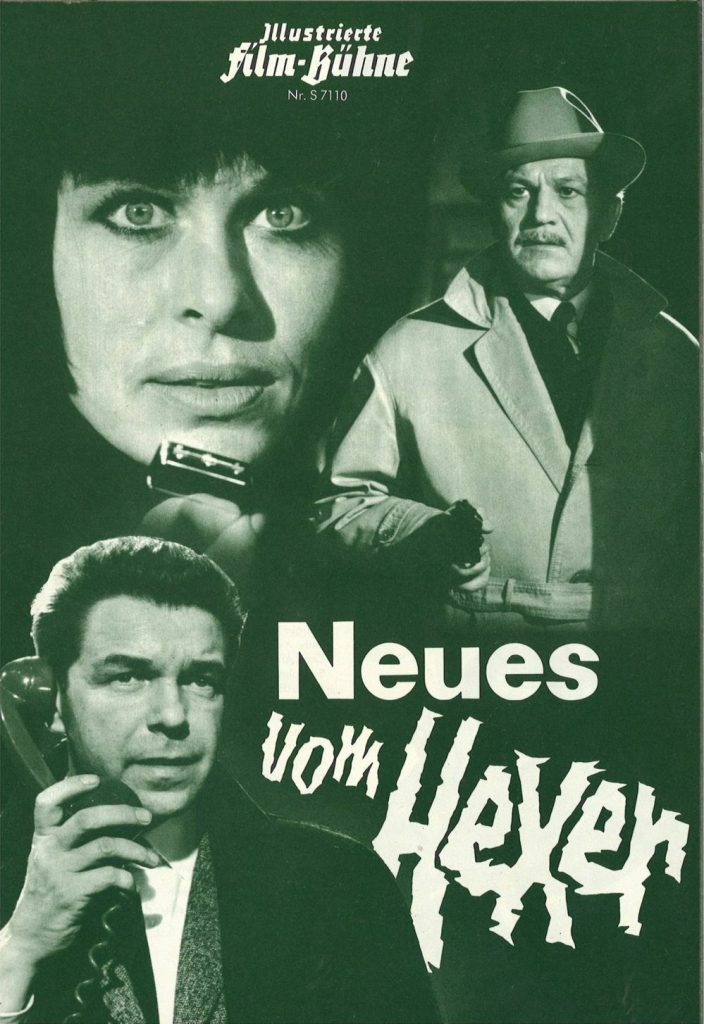

![[September 26, 1964] A Mystery Mastermind Double-Feature: The Ringer and The Death Ray of Dr. Mabuse](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/hexer-499x372.jpg)

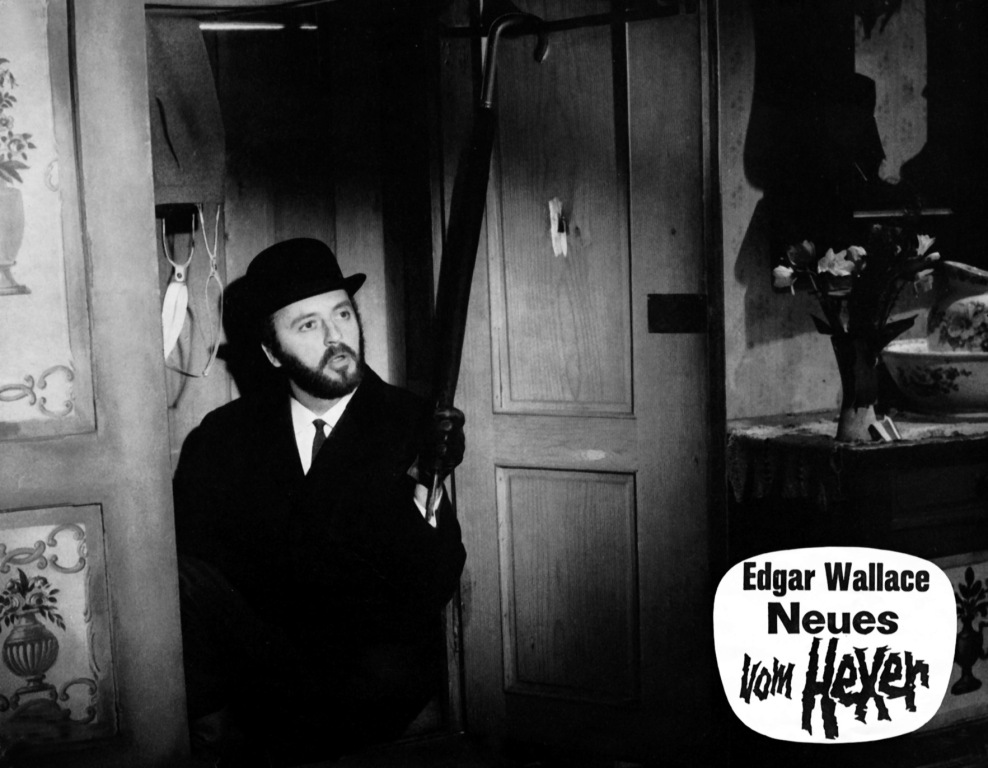

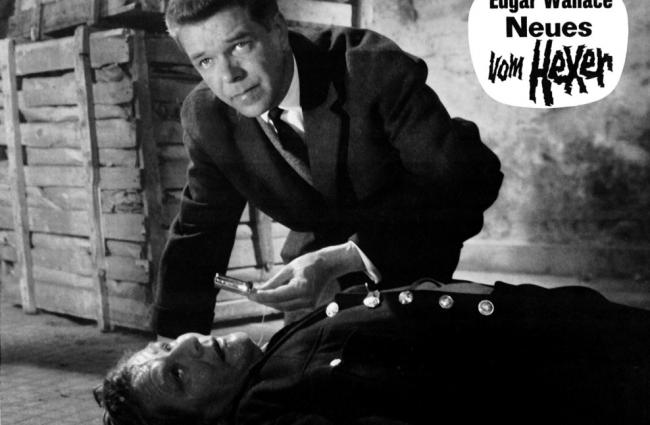

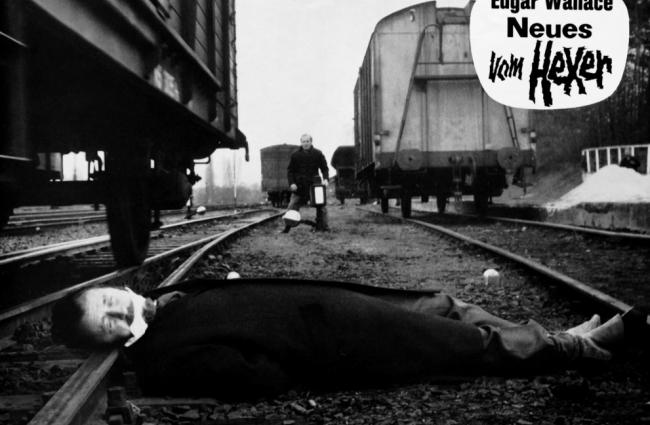

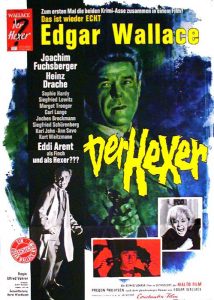

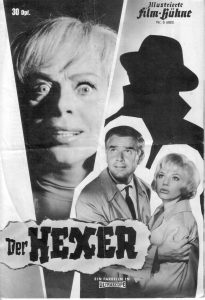

Der Hexer (The Ringer) is the twentieth Edgar Wallace adaptation produced by Rialto Film and one of the best, if not the best movie in the series so far. The Ringer is a pure delight and a distillation of everything that has made the Edgar Wallace series so successful. The balance of humour and thrills is just right and The Ringer will have you both rolling on the floor with laughter and on the edge of your seat with suspense. There are nefarious crimes, a mysterious figure – for once not the villain – whose true identity is not revealed until the final reel and a twisting and turning plot that still has a twist or two in store, even after the Ringer has been unmasked.

Der Hexer (The Ringer) is the twentieth Edgar Wallace adaptation produced by Rialto Film and one of the best, if not the best movie in the series so far. The Ringer is a pure delight and a distillation of everything that has made the Edgar Wallace series so successful. The balance of humour and thrills is just right and The Ringer will have you both rolling on the floor with laughter and on the edge of your seat with suspense. There are nefarious crimes, a mysterious figure – for once not the villain – whose true identity is not revealed until the final reel and a twisting and turning plot that still has a twist or two in store, even after the Ringer has been unmasked. The Ringer is based on Edgar Wallace's 1925 novel The Gaunt Stranger and its 1926 stage version The Ringer, though the literal translation of the German title would be "The Witcher". It's certainly apt, for the titular character is not just a master of disguise, but also has nigh sorcerous abilities to evade Scotland Yard's finest.

The Ringer is based on Edgar Wallace's 1925 novel The Gaunt Stranger and its 1926 stage version The Ringer, though the literal translation of the German title would be "The Witcher". It's certainly apt, for the titular character is not just a master of disguise, but also has nigh sorcerous abilities to evade Scotland Yard's finest. Unbeknownst to the killers, the murdered woman was Gwenda Milton, the younger sister of Arthur Milton, the vigilante known only as the Ringer for his uncanny ability to disguise himself as anybody he pleases. Years ago, Arthur Milton had given up his career of vigilantism and retired to Australia, far beyond the reach of the British law. But now he is back to take revenge on the murderers of his sister. Of course, both the villains and Scotland Yard are only too eager to capture the Ringer. There is only one problem. No one knows what he looks like.

Unbeknownst to the killers, the murdered woman was Gwenda Milton, the younger sister of Arthur Milton, the vigilante known only as the Ringer for his uncanny ability to disguise himself as anybody he pleases. Years ago, Arthur Milton had given up his career of vigilantism and retired to Australia, far beyond the reach of the British law. But now he is back to take revenge on the murderers of his sister. Of course, both the villains and Scotland Yard are only too eager to capture the Ringer. There is only one problem. No one knows what he looks like.

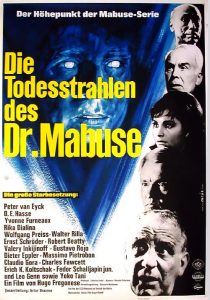

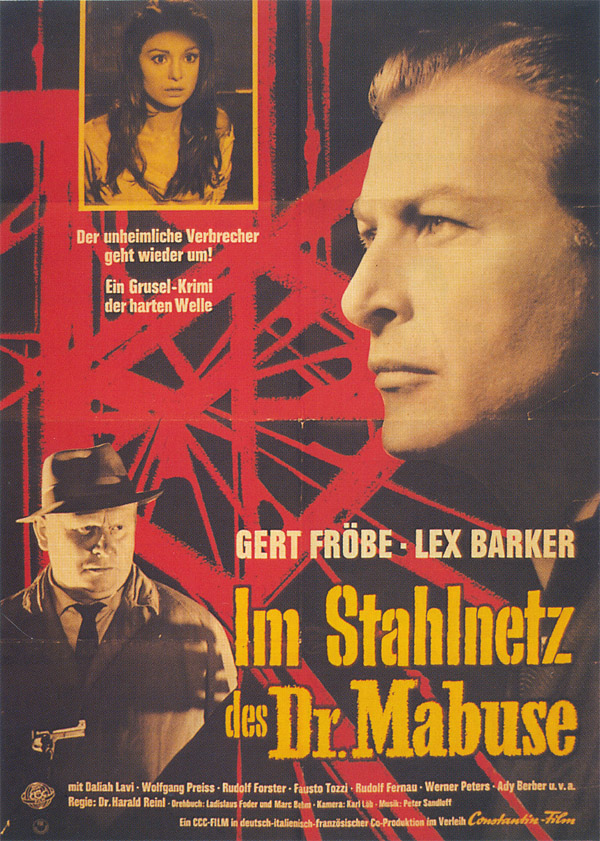

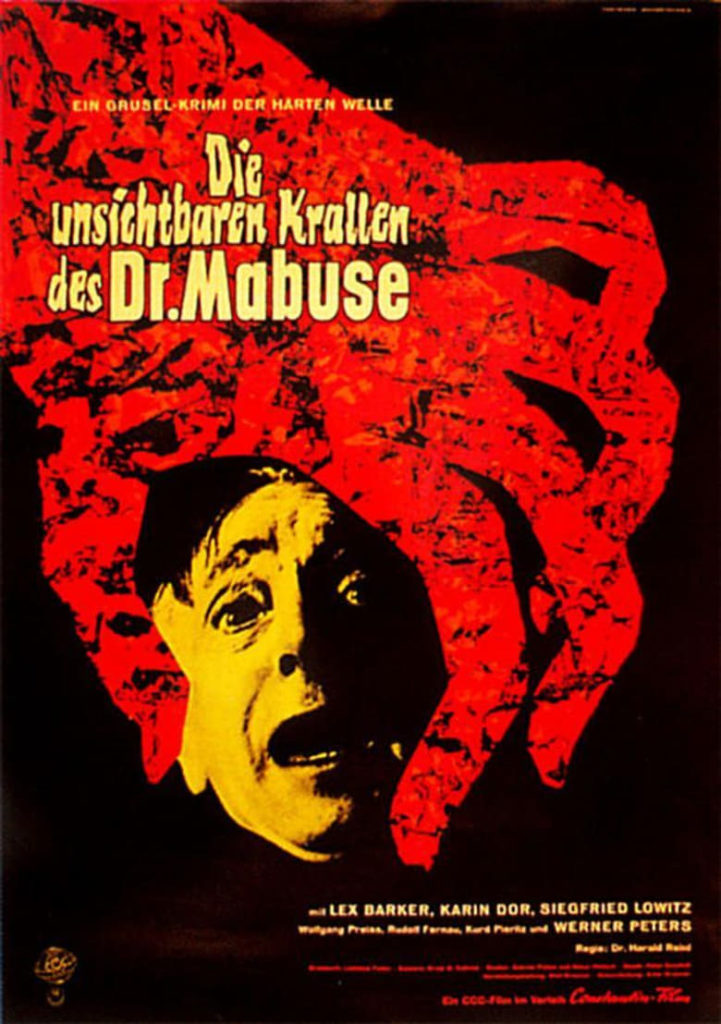

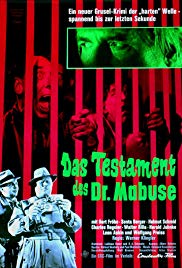

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for the latest movie in the other great West German thriller series. For while the Dr. Mabuse series has been very good at reinventing itself in the five movies made post WWII (plus two made during the Weimar Republic) so far, the latest instalment Die Todesstrahlen des Dr. Mabuse (The Death Ray of Dr. Mabuse) shows definite signs of the series going stale.

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for the latest movie in the other great West German thriller series. For while the Dr. Mabuse series has been very good at reinventing itself in the five movies made post WWII (plus two made during the Weimar Republic) so far, the latest instalment Die Todesstrahlen des Dr. Mabuse (The Death Ray of Dr. Mabuse) shows definite signs of the series going stale.

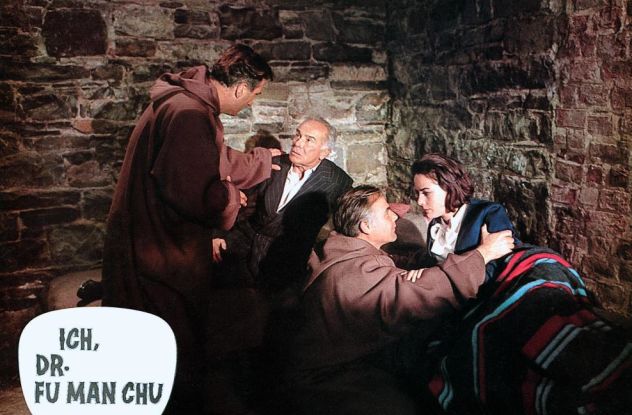

Not long after Pohland's disappearance, Anders is given a new assignment – to investigate spy activities in Malta, where a scientist named Professor Larsen is working on an invention that will change the world. And that invention just happens to be a death ray. Anders no more thinks that this is a coincidence than the audience does. So he hastens to Malta, taking along Judy (former Miss Greece Rika Dialina), one of his many girlfriends, to pose as a newlywed couple on their honeymoon.

Not long after Pohland's disappearance, Anders is given a new assignment – to investigate spy activities in Malta, where a scientist named Professor Larsen is working on an invention that will change the world. And that invention just happens to be a death ray. Anders no more thinks that this is a coincidence than the audience does. So he hastens to Malta, taking along Judy (former Miss Greece Rika Dialina), one of his many girlfriends, to pose as a newlywed couple on their honeymoon.

![[July 8, 1964] The Immortal Supervillain: The Remarkable Forty-Two Year Career of Dr. Mabuse](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Testament-1933-386x372.jpg)

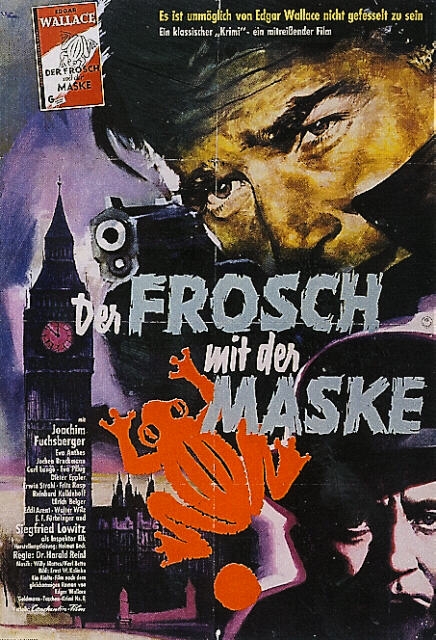

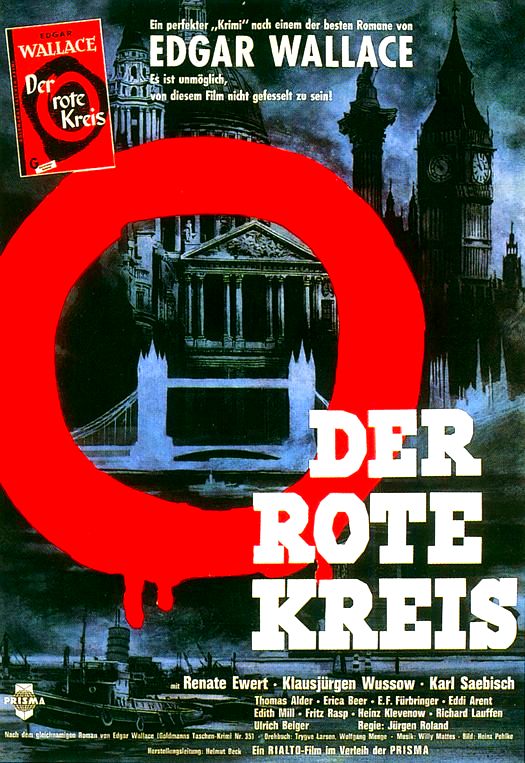

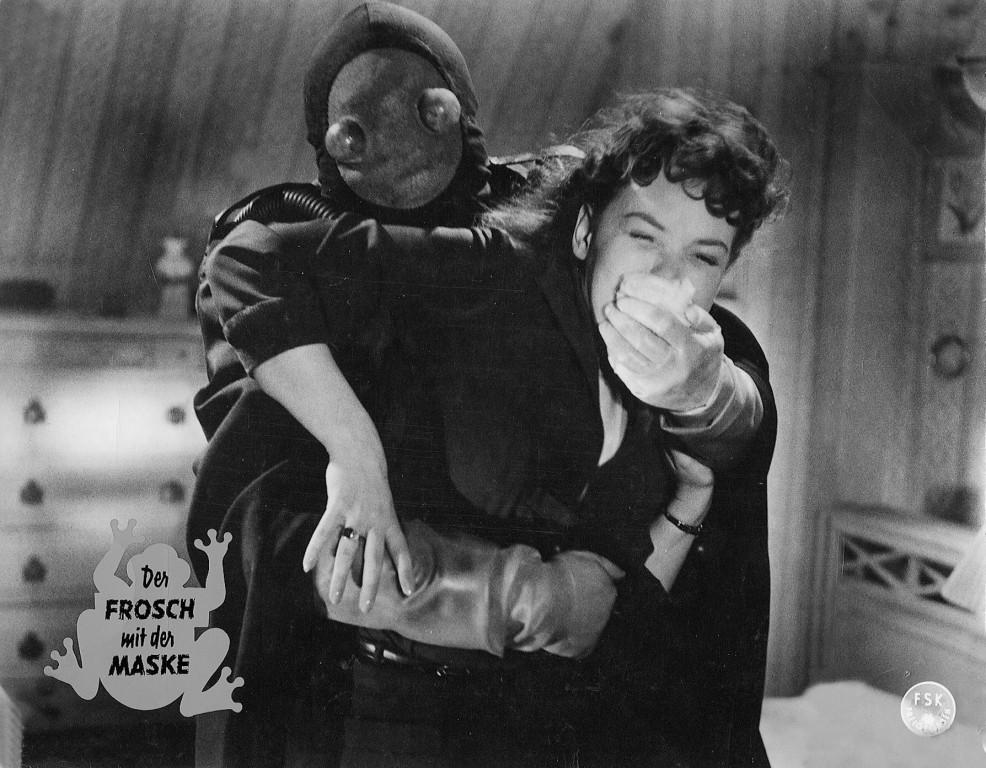

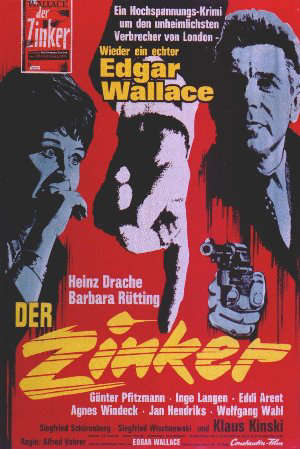

![[June 4, 1964] Weird Menace and Villainy in the London Fog: The West German Edgar Wallace Movies](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/640604The_Green_Archer-672x372.jpg)

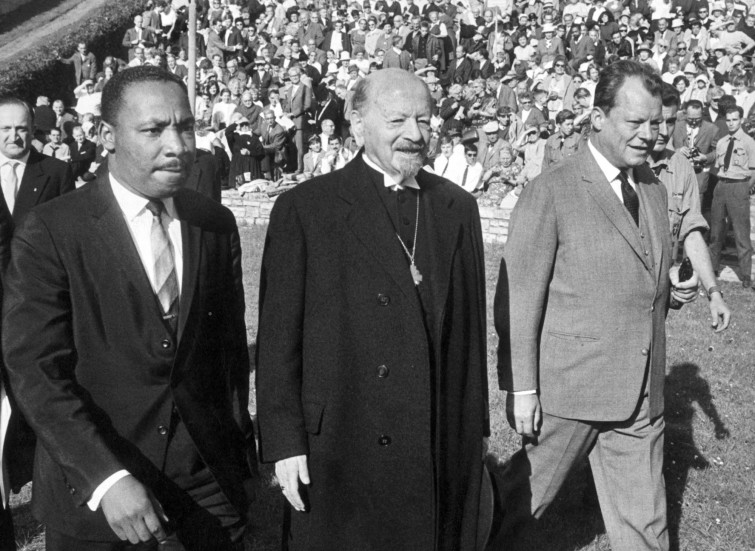

![[November 24, 1963] Mourning on two continents](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/631123Flowers_Schoeneberger_Rathaus-672x372.jpg)

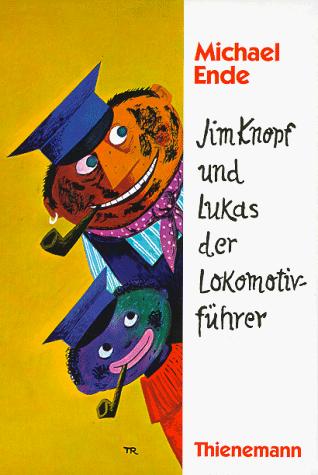

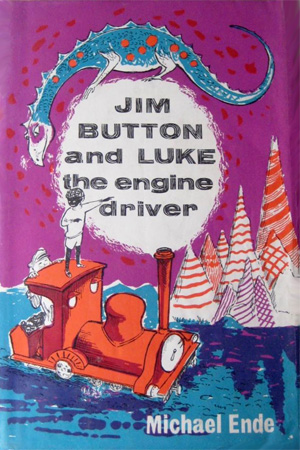

![[Oct. 30, 1963] <i>Jim Knopf and Lukas the Train Engine Driver</i> by Michael Ende: A Classic in the Making](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/631030Cover_Jim_Knopf_English.jpg)