by Gideon Marcus

Over There

It seems like only yesterday that a minor naval engagement in the Gulf of Tonkin off the coast of Vietnam embroiled the world's mightiest nation in a struggle against Communism in Southeast Asia. Less than a year later, the American commitment totaled 100,000 troops. Today, as the last aftershocks of the second Tet Offensive are beaten back from Saigon, more than half a million soldiers are fighting and dying in those far off jungles and cities.

It's a war unlike any other we've fought, though perhaps not unlike wars our allies have fought–there's a reason why the British, who fought an ultimately successful anti-guerrilla war in Malaya, have declined to join us in Vietnam. It's not really a war for territory, nor a total war, as we fought against the Nazis or the Japanese. It's a holding action, a war for "hearts and minds", holding the bag until the South Vietnamese can fight for themselves–if, indeed, that will ever be possible.

So new and unusual is this conflict that one would hardly expect it to be a viable subject for board wargaming. After all, the pushers of counters on hex grids have largely stuck to World War 2 and the Civil War for their battlefields, highly researched and decently distant as they are.

And yet, just one year after Tonkin, Game Science came out with Viet Nam, a sophisticated wargame covering the war on a strategic level. Could a game developed so early in the conflict have any chance of modeling reality? And is it any fun? This Memorial Day, we took the game for a spin and came to some very interesting conclusions.

In the trenches

The first thing one notices about Viet Nam is the board. Rather than use the hex grid that has become de rigueur these last several years, it reverts to areas like in last decade's Diplomacy. This makes sense. Viet Nam is not a game of tactical maneuvers but of strategic province control.

The Allied forces (Americans, ARVN, Koreans, Filipinos, Australians) and the Communists (Viet Cong and NVA) start out splitting the provinces between them. Control is indicated with a little bingo disc that represents a local militia. Each side also gets a number of regular armies, the Allies starting with more, but acquiring them at half the rate of the Communists. The regular armies are important because they are the only units that can both move and hold ground, the local militias adding strength but being both immobile and subject to flipping by the enemy.

The Allies also get air units that can be used for tactical support of armies (adding to their strength), strategic bombing of provinces (with a chance of destroying Communist units in the area), interdicting the Ho Chi Minh Trail (which kills Communist reinforcements) and mass bombing of North Vietnam (which earns victory points). Bad weather in the summer and fall months limits strategic air missions.

Each turn, simulating one month, begins with both sides allocating ten factors towards various political activities: bolstering/destabilizing the government, terrorism/counter-terrorism, psychological warfare (to flip militias), seeking world favor (worth victory points), and ambush/counter-ambush (a trap for Allied armies). This is essentially Rock-Paper-Scissors and the place where the Communists can win the game. Unless the Allies guess right every time, they will lose stability or provinces, each of which leads them down the path of losing victory points. Once below a certain level, they go down to nine or fewer factors to apply in this phase, which is a spiral of doom toward defeat.

After the political phase, both sides plot their moves in secret. The Communists are trying to seize provinces and Allied bases. The Allies are seizing provinces, defending, and allocating air power. As the Communist players in our game quickly learned, randomness is key–there are always a dozen places they can attack, and the less consistent they are, the less chance the Allies will anticipate and head off an attack.

Combat is another kind of Rock-Paper-Scissors, each side having a set of four cards depicting various attack strategies. In each conflict, the two players choose cards and then compare the two to determine the result. For the Americans, the outcome is either inconclusive or a victory resulting in the loss of a regular army. For the Communists, they are either forced to retreat or they win. In other words, this is a part of the game the Communists will also ultimately win once they understand the cards, as the Allies cannot guess right every time, and they run out of armies faster than the Communists. The more provinces under Communist control, the more mobility they get, again building momentum toward victory.

So is the game hopeless for the Allies? Maybe not. The game begins in January 1965, when weather is excellent. Optimal strategy suggests that the Allies should interdict the NVA for those good months, allowing the Allies to build up an army superiority. The Communists can only really run rampant if they have the regular troops for it. If any air power be left over, the Allies should immediately start bombing North Vietnam as it is the only sure way to get victory points–it is the Allied counterpart to the Communists' political factor advantage.

Provided the Allies can contain the NVA and make lucky guesses to keep the Communists stalled, it is possible that, over time, the Communists will be forced below 10 political points per turn and, themselves, end up on the slide to defeat. It'd be a long slog, but it is at least conceivable.

Proof in the pudding

I spotted Viet Nam not at my local game store, but in the campus store at the new campus of University of California San Diego. Though the copyright on the game is 1965, various references in the rules and components suggest this is a brand new edition, updated based on three years of conflict. Thus, I don't know how prescient the original was.

That said, the game seems to suggest that unless the United States goes bombing right out of the gate, as many generals urged us to do, there is no chance of victory. Even a six month delay results in swarms of NVA and endless Red provinces. Moreover, even had we gone in, bombs blazing (and what might the political ramifications vis. a vis. the Soviets been of that?), Viet Nam suggests that victory still would not have been certain, and it would have taken a long time.

It seems like an accurate simulation to me!

But is it fun? Well, we enjoyed it at the time, all eight hours that we played before the Allies conceded the game to the Communists in latter 1965. But on further analysis, there actually isn't that much to enjoy. It's all a matter of luck, see-sawing back and forth on the victory point chart, until a lucky break drives the meter over to either a win or the inevitable road to defeat.

Thus, Viet Nam is less a game and more a puzzle–and a lesson. Once the puzzle be solved and the lesson absorbed, there is not much replay value.

Just like the real war…

</small

</small

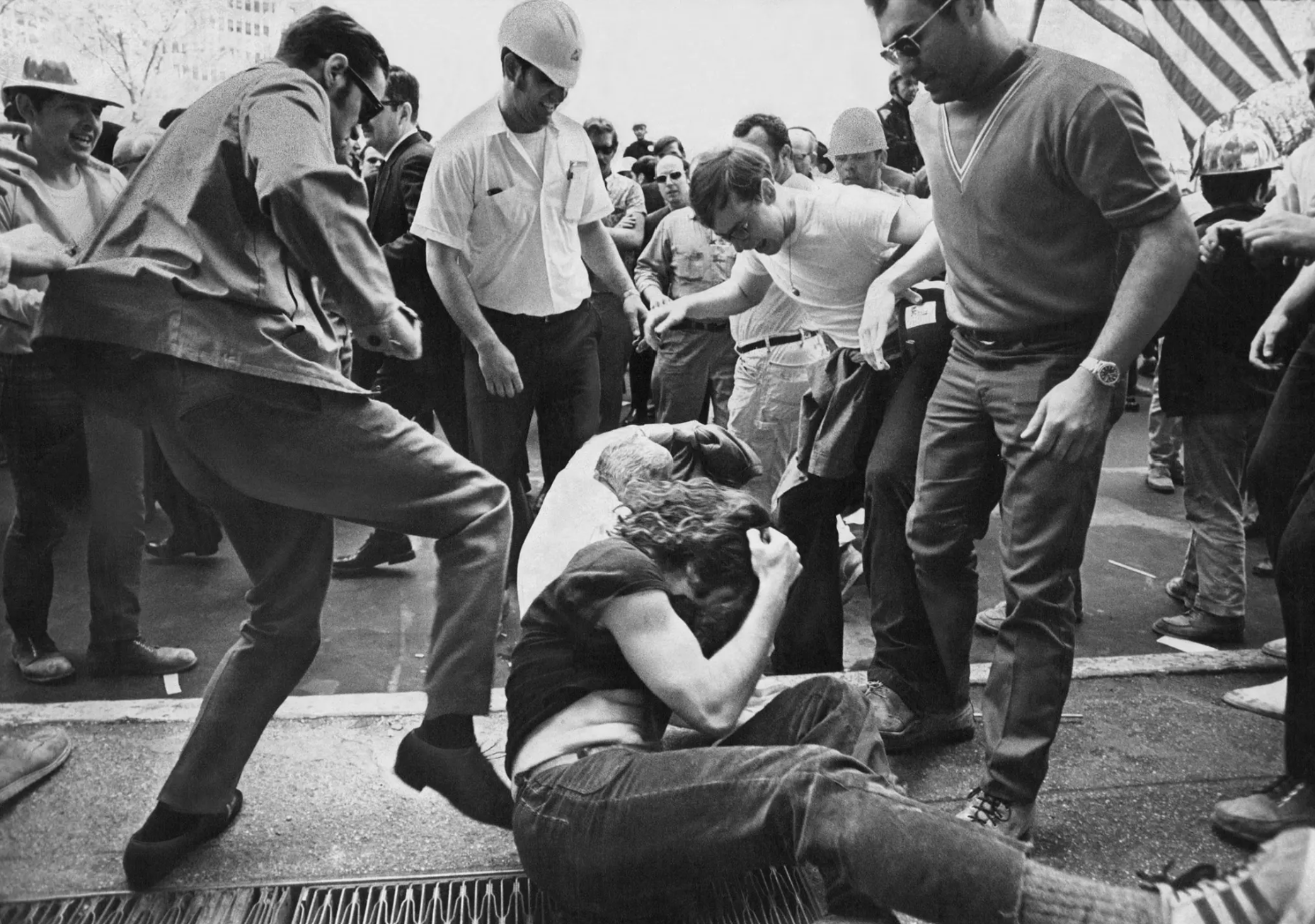

![[June 26, 1970] Hard Hats & Flower Power Collide](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Screenshot-2025-06-18-230824-672x372.png)

![[June 20, 1968] Art imitates Life (the wargame <i>Viet Nam</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/680620cover-1-672x372.jpg)