by Gideon Marcus

February and March have been virtually barren of space shots, and if Gordo Cooper's Mercury flight gets postponed into May, April will be more of the same. It's a terrible week to be a reporter on the space beat, right?

Wrong!

I've said it before and I'll say it again. Rocket launches may make for good television, what with the fire, the smoke, and the stately ascent of an overgrown pencil into orbit…but the real excitement lies in the scientific results. And this month has seen a tremendous harvest, expanding our knowledge of the heavens to new (pardon the pun) heights. Enjoy this suite of stories, and tell me if I'm not right…

How hot is it?

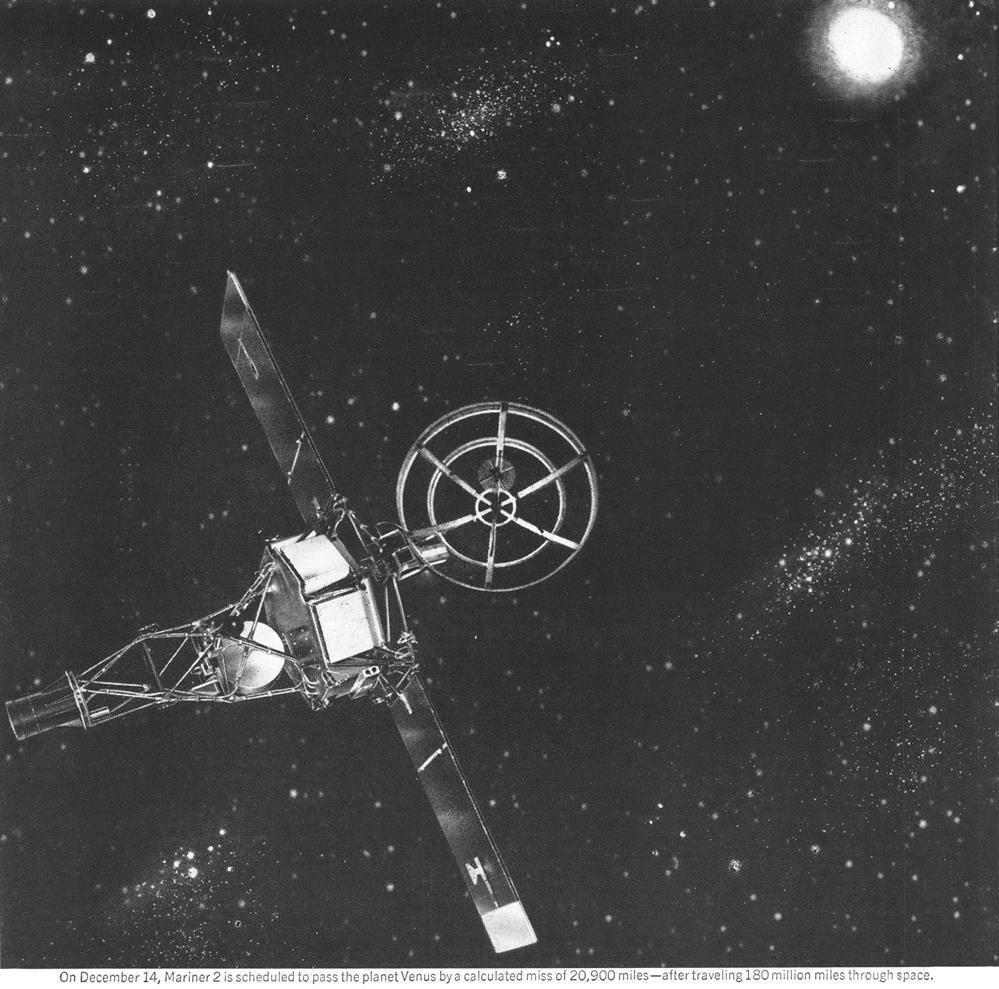

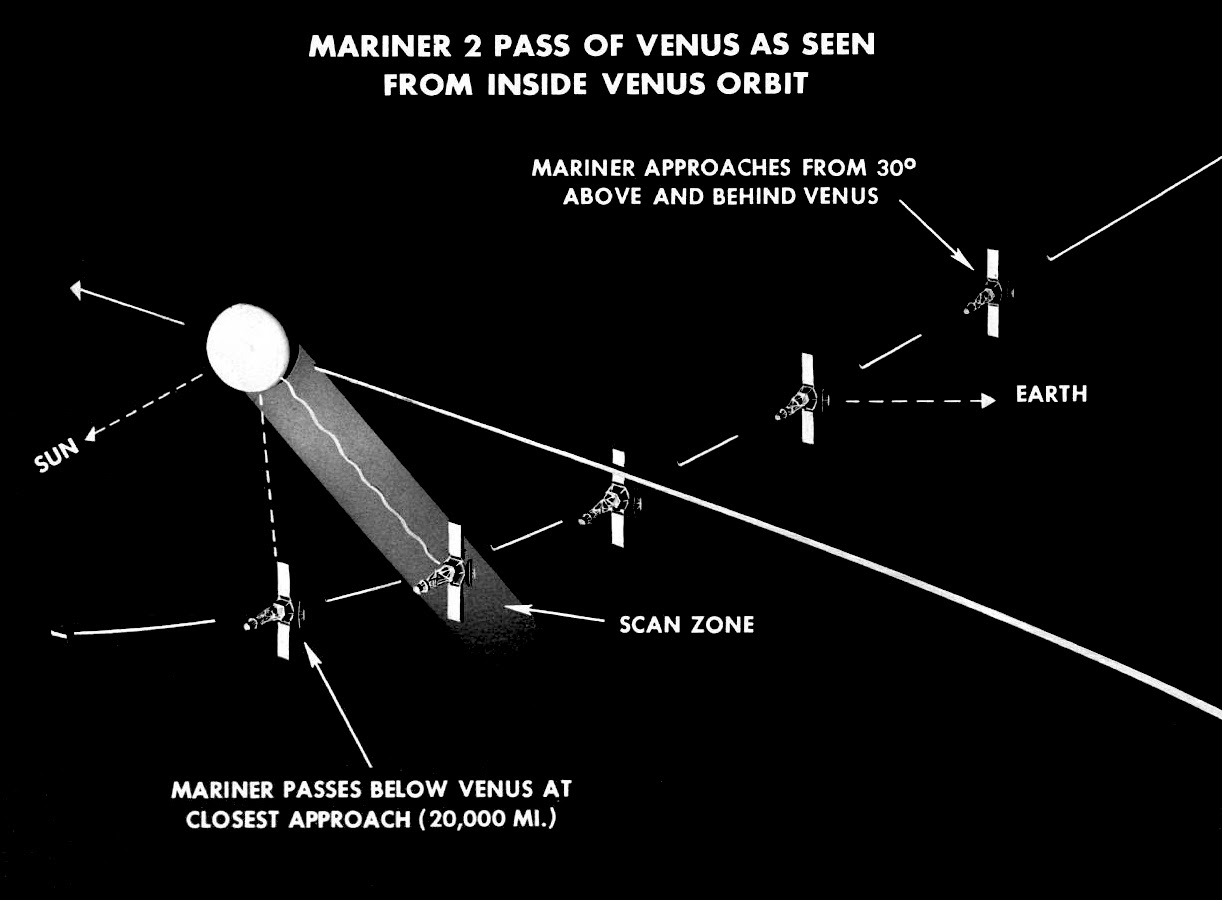

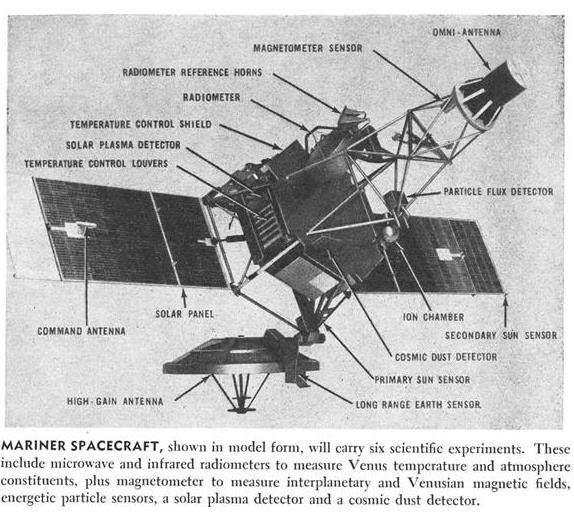

Mariner 2 went silent more than two months ago, but scientists are still poring over the literal reams of data returned since its rendezvous with Venus. The first interplanetary mission was a tremendous success, revealing a great deal about the Planet of Love, whose secrets were heretofore protected by distance and a shroud of clouds.

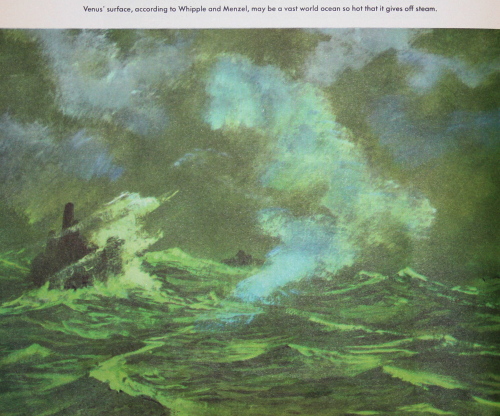

Here's the biggie: Preliminary reports suggested that the surface temperature of "Earth's Twin" is more than 400 degrees Fahrenheit. It turns out that was a conservative estimate. In fact, the rocky, dry landscape of Venus swelters at 800 degrees — possibly even hotter than the day side of sun-baked first planet, Mercury. It's because the planet's dense carbon dioxide atmosphere acts like a heat blanket. There's no respite on the night side of the hot world either; the thick air spreads the temperatures out evenly.

Thus, virtually every story written about Venus has been rendered obsolete. Will Mariner 3 destroy our conception of Mars, too?

Just checking the lights

On February 25, the Department of Defense turned little Solrad 1 back on after 22 months of being off-line. The probe had been launched in conjunction with a navigation satellite, Transit, back in June 1960. For weeks, it had provided our first measurements of the sun's X-ray output (energy in that wavelength being blocked by the Earth's atmosphere and, thus, undetectable from the ground). DoD has given no explanation for why the probe has been reactivated, or why it was turned off in the first place. Maybe there's a classified payload involved?

Radio News from the Great White Spacecraft

Last September, the Canadians launched their first satellite — the "top-sounder," Alouette, whose mission was to measure the radio-reflective regions of our atmosphere from above. The results are in, and to any HAM or communications buff, its huge news.

It turns out that the boundaries of the ionosphere are rougher at higher latitudes than at lower latitudes. Moreover, Alouette has determined that the Van Allen Belts, great girdles of radiation around our planet, dip closer to the Earth at higher latitudes. This heats up the ionosphere and causes the roughness-causing instability. — the more active the electrons, the poorer the radio reflection. Now we finally know why radio communication is less reliable way up north. The next step will be learning how to compensate for this phenomenon so that communication, both civil and military, can be made more reliable.

Sun Stroke Warning

After a year in orbit, NASA's Orbiting Solar Observatory is still going strong, with 11 of 13 experiments still functioning. The satellite has probably returned more scientifically useful data than all of the ground-based solar observatories to date (certainly in the UV and X Ray spectra, which is blocked by the atmosphere).

Moreover, OSO 1 has returned a startling result. It turns out that solar flares, giant bursts of energy that affect the Earth's magnetic field, causing radio storms and aurorae, are preceded by little microflares. The sequence and pattern of these precursors may be predictable, in which case, OSO will give excellent advance warning of these distruptive events.

Tax money at work, indeed!

Galaxy, Galaxy, Burning Bright

In the late 1950s, astronomers began discovering some of the brightest objects in the universe. It wasn't their visible twinkle that impressed so much as their tremendous radio outbursts. What could these mysterious "quasi-stellar sources" be?

Now we have a pretty good guess, thanks to a recent scientific paper. Cal Tech observers using the Mt. Wilson and Mt. Palomar observatories turned their gaze to object 3C 273, a thirtheenth magnitude object in the constellation of Virgo. It turns out that 3C 273's spectrum exhibits a tremendous "red shift," that is to say, all of the light coming from it has wavelengths stretched beyond what one would expect. This is similar to the decrease in pitch of a railroad whistle as the engine zooms away from a listener.

The only way an object could have such a redshift is if it were of galactic proportions and receding from us at nearly 50,000 km/sec. This would place it almost 200,000,000 light years away, making it one of the most distant (and therefore, oldest) objects ever identified.

At some point, astronomer Hubble's contention that the universe is expanding is likely to be confirmed. These quasi-stellar objects ("quasars"?) therefore represent signposts from a very young, very tiny universe. What exciting times we live in!

Five years of Beep, Beep

St. Patricks Day, 1958 — Vanguard 1 was the fourth satellite in orbit, but it was the first civilian satellite, and it is the oldest one to remain up there. In fact, it is the only one of the 24 probes launched in the 1950s that still works.

What has a grapefruit-sized metal ball equipped with a radio beacon done for us? Well, plenty, actually. Because it has been tracked in orbit so long, not only have we learned quite a bit about the shape of the Earth (the variations in Vanguard's orbit are due to varying gravities on the Earth, the measurement of which is called "geodetics"), but the satellite's slow decay also tells us a lot about the density of the atmosphere several hundred miles up.

So, while Sputnik and Explorer might have had the first laughs, Vanguard looks likely to have the last for a good long time.

Telstar's little brother does us proud

RCA's Relay 1, launched in December, is America's second commercial communications satellite. It ran into trouble immediately upon launch, its batteries producing too little current to operate its transmitter. Turns out it was a faulty regulator on one of the transponders; the bright engineers switched to the back-up (this is why you carry a spare!), and Relay was broadcasting programs across the Atlantic by January. 660 orbits into its mission and 500 beamed programs later, NASA announces that Relay has completed all tests.

Nevertheless, why abandon a perfectly good orbital TV station? Relay will continue to be used to transmit shows transcontinentally, especially now that Telstar has finally gone silent (February 21). There is even talk that Relay could broadcast the Tokyo Olympics in 1964, if it lasts that long!

In a sea of Blue, a drop of Red

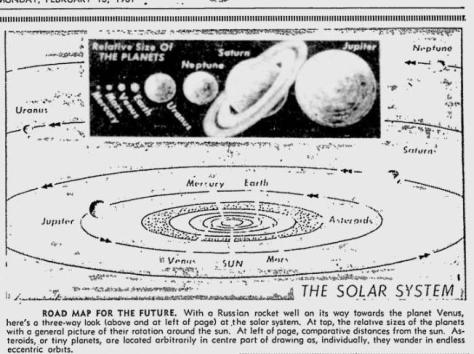

On March 12, 3-12 at the Spring Recognition Dinner of Miracle Mile Association, in Los Angeles, Cal Tech President, Lee DuBridge, noted that the United States has put 118 probes into space, while the Russians have only lofted 34 (that we know of). He also pointed out that virtually no scientific papers have resulted from the Soviets' "science satellites."

As if in reply, on March 21 the Soviets finally, after 89 days without a space shot, launched Kosmos 13. (To be fair, it's been kind of quiet on the American side, too). The probe was described as designed to "continue outer space research." No description of payload nor weight specifications were given. Its orbit is one that allows it to cover much of the world. While it may be that some of the Kosmos series are truly scientific probes, you can bet that, like America's Discoverer program, the Kosmos label is a blind to cover the Russians' use of spy satellites. Oh well. Turnabout is fair play, right?

[Next up, don't miss Mark Yon's spotlight of this month's New Worlds! And if I saw you at Wondercon, do drop me a line…]