by David Levinson

A piece of the rock

Anyone who pays more than casual attention to U.S. domestic news is probably aware of the Black Power movement, but how many have heard of the Red Power movement? Those whose ancestors were in what is today the United States have been shamefully treated. They’ve been repeatedly driven from their homes and sacred lands, seen treaty after treaty ignored and violated, been robbed of their languages and religions, and much more. Now some of them are trying to regain some of what they’ve lost.

Back in 1963, the federal prison on the island of Alcatraz in San Francisco Bay was declared no longer fit for purpose and shut down. A Sioux woman living in the area recalled that the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie promised that land occupied by the federal government would revert to the native peoples if it was no longer in use. In March of the following year, she and several others staged a four-hour occupation of the island and filed a claim. They left when threatened with felony charges.

Last October, a fire destroyed the San Francisco Indian Center, and the loss of the space reminded Native Americans in the Bay Area of one of the proposals for the use of Alcatraz by those earlier protesters. On November 20th, a group of 89 people calling themselves Indians of All Tribes set out to reach Alcatraz, with fourteen of them successfully reaching the island. They have since been joined by many more; there are a few hundred people there now.

Some of the occupiers a few days after arriving on Alcatraz.

Some of the occupiers a few days after arriving on Alcatraz.

There have been difficulties. Water and electricity are particular problems. Many hippies flocked to the island until non-Indians were prohibited from staying overnight. A fire in early June destroyed several buildings. And in May, the government began the process of transferring Alcatraz to the National Park System in order to blunt the occupiers’ claim.

However, they’ve garnered a lot of attention and support, including from many celebrities. They have also inspired other protests in favor of Indian rights. After a Menominee woman in Chicago was evicted following a rent strike over repairs not being made, a protest camp was set up in a nearby parking lot, starting with a tepee borrowed from the local American Indian Center. Since it’s right next to Wrigley Field, where the Cubs play baseball, it’s gotten a lot of attention and has been dubbed “little Alcatraz” in the local press.

Will all of this achieve anything? Maybe. The scuttlebutt in Washington is that Nixon is planning a proposal to Congress sometime this month regarding Indian rights. There are no details right now, but it’s expected that he will call for greater self-determination and an end to forced assimilation.

Continue reading [July 2, 1970] Matters of conscience (August 1970 Venture)

![[July 2, 1970] Matters of conscience (August 1970 <i>Venture</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Venture-1970-08-Cover-486x372.jpg)

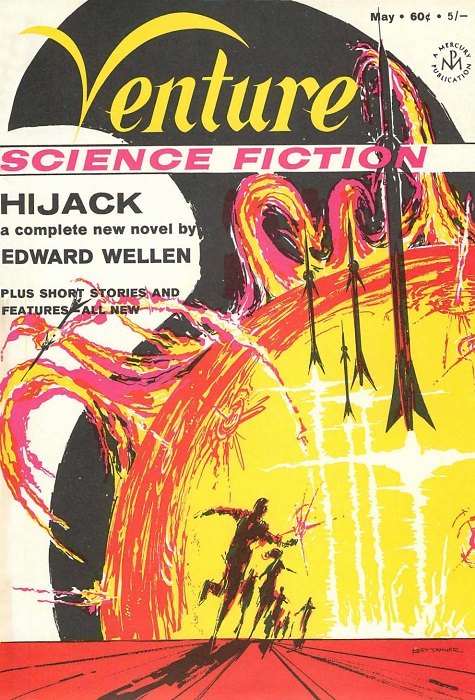

![[April 14, 1970] Take this spaceship to Alpha Centauri (May 1970 <i>Venture</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Venture-1970-05-Cover-475x372.jpg)

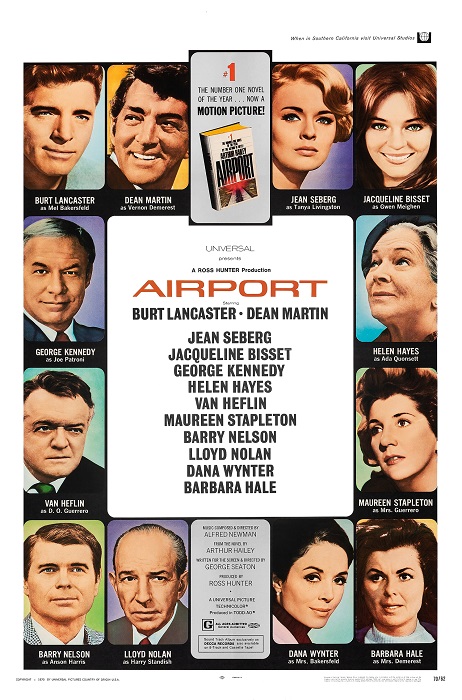

You probably know who most of these people are.

You probably know who most of these people are. I’m still not sold on Tanner’s covers, but this one is better than most. Art by Bert Tanner

I’m still not sold on Tanner’s covers, but this one is better than most. Art by Bert Tanner![[January 14, 1970] Root Rot (February 1970 <i>Venture</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Venture-1970-02-Cover-483x372.jpg)

A not very representational image for Laumer’s new story. Art by Bert Tanner

A not very representational image for Laumer’s new story. Art by Bert Tanner![[October 20, 1969] There was a ship (November 1969 <i>Venture</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Venture-1969-11-Cover-480x372.jpg)

The SS Manhattan breaking through the ice of the Northwest Passage.

The SS Manhattan breaking through the ice of the Northwest Passage. Art by Tanner

Art by Tanner![[July 2, 1969] Merging streams (August 1969 <i>Venture</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Venture-1969-08-Cover-543x372.jpg)

More geometric shapes and color washes. Art by Bert Tanner

More geometric shapes and color washes. Art by Bert Tanner