[if you’re new to the Journey, read this to see what we’re all about!]

by Gideon Marcus

What if the good guys had lost World War 2?

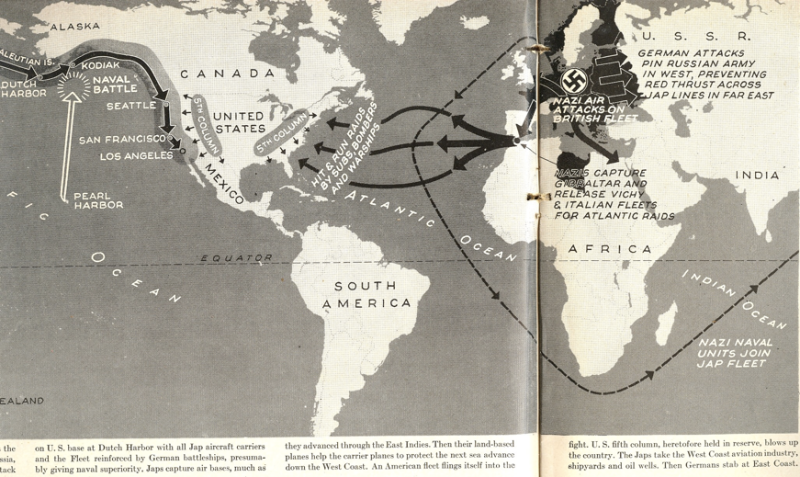

Imagine a United States split in three pieces: the East Coast is a protectorate of the Reich. The West has been colonized by the Japanese. A rump free state sprawls across the Rockies and western Plains. The Holocaust has extended to Africa, and the two fascist superpowers are locked in a Cold War with stakes as high, if not higher than in our real world.

Philip K. Dick has returned to us after a long hiatus with a novel, The Man in the High Castle. It is an ambitious book, long for a science fiction novel. Castle's setting is an alternate history, one in which the Axis powers managed to defeat the Allies…somehow (it is never explained). Dick explores this universe through five disparate viewpoint protagonists, whose paths intertwine in complex, often surprising ways:

Major Rudolf Wegener: An agent of the Abwehr, the German foreign espionage service known for its subversive, anti-Nazi activities. Wegener is desperate to make contact with the Japanese government to inform them of a German plan to turn the Cold War hot – a conflict the Japanese cannot win. His contact intermediary is…

Nobusuke Tagomi: Head of the Japanese trade mission in San Francisco, a deeply spiritual and traditional man who abhors violence. Like many Japanese posted in the former United States, he has an outsized fancy for American antiques such as those provided by…

Robert Childan: A prissy antiques dealer, who accepts the superiority of the ancient civilizations of the Far East, having adopted the Japanese mindset almost entirely. He is resolved to dismantle the cultural heritage of his nation one little treasure at a time – that is, until he discovers a new American culture growing like a flower in a footprint, a culture represented by the art whose creator is…

Frank Frink: Formerly a forger of American historical artifacts, he has turned his expertise to the creation of exquisite modern jewelry. He is a Jew in a world where being a Jew is a capital crime. He is married to but long-separated from…

Juliana Frink: A ravishing beauty and Judo expert living on her own in the Rocky Mountain States. She links up with a mournful Italian truck driver who turns out to be an SD (Nazi secret police) assassin tasked with murdering the author of…

The Grasshopper lies heavy: A sort of sixth character that unites the protagonists. It is a novel of alternate history in which Germany and Japan lost the Second World War. Banned in the Reich and Reich-controlled countries, it is a best-seller elsewhere. Its window on a world in which fascism did not triumph offers a scrap of hope, a vision of a world where sanity prevailed. It is interesting to note that the timeline of Grasshopper is not that of our universe, but one in which the British and Americans are the post-war superpowers.

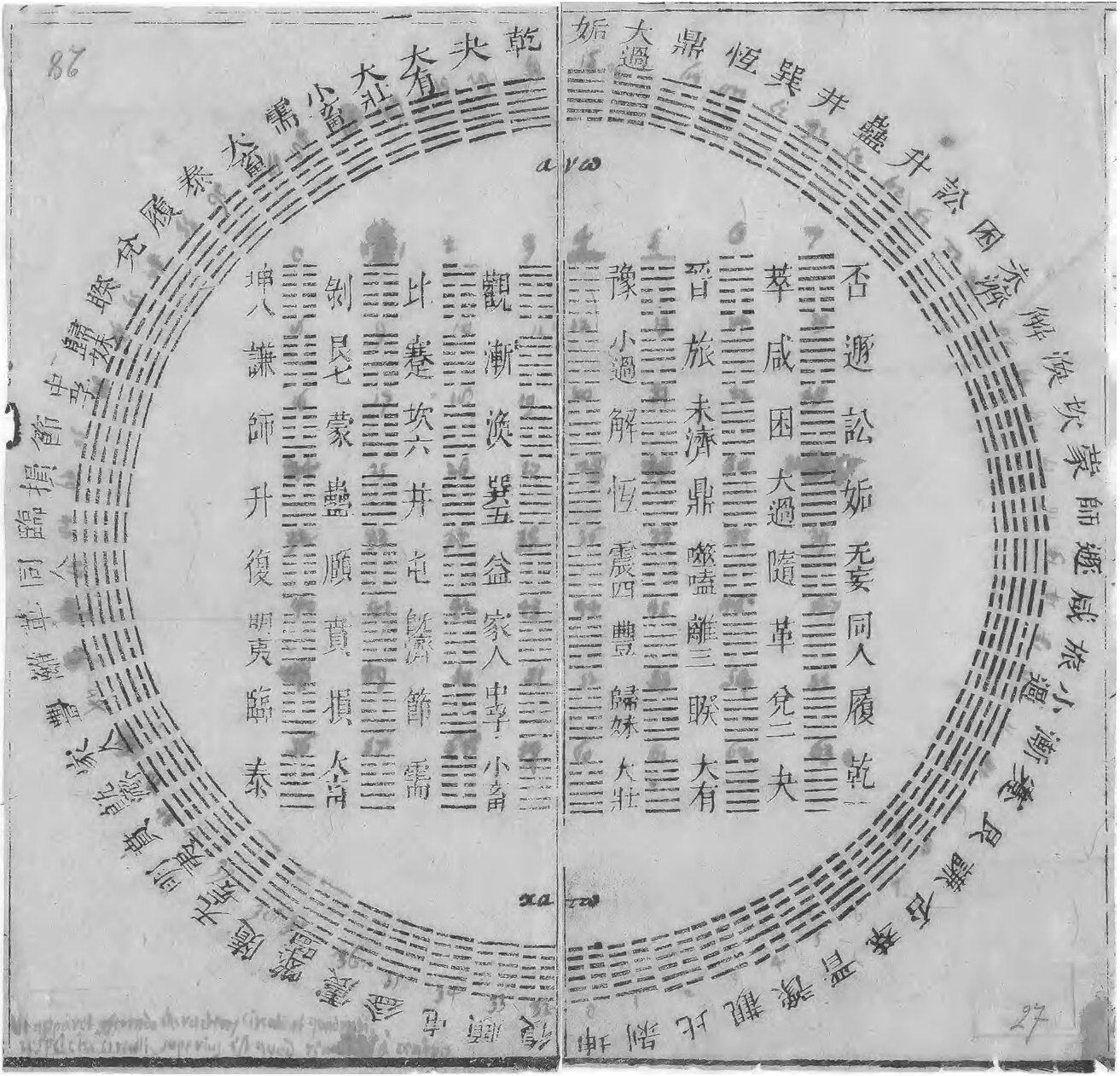

There is a strong suggestion that what makes the world of Grasshopper so compelling is that it is, in fact, the real world. This goes beyond wishful thinking. At one point, Tagomi actually wills himself away from Castle's timeline. Castle's author, Hawthorne Abendsen confesses that he did not so much write Grasshopper as simply draft it per the dicta of the I Ching, an ancient Chinese oracle book whose use is widespread in the Japanese-influenced regions, and which Abendsen consulted throughout the writing of his book.

Castle takes a good third of its length to really get started. Ostensibly a thriller of an alternate Cold War, it is really a character study focused on the myriad minutiae of interaction. How do conqueror and conquered interact? How complete can cultural assimilation be? What is the character of pride in a defeated race? These are all good questions, and Dick does a decent job giving his take on their answers.

There are significant problems with Castle, however. For one, it suffers from lazy worldbuilding. The book is an opportunity for Dick to draw a wide cast of characters and depict their complex web of interactions. But the underpinnings of the world they inhabit are implausible. First and foremost, it would have been impossible, logistically, for the United States to have fallen to the Axis Powers. For that matter, I have doubts that the Soviet Union was ever in existential danger. Certainly the Reich never came close to making The Bomb – their racial theory-tinged science wouldn't have allowed it. It is sobering when you realize that the Allies managed to fight two world wars and develop the most expensive and powerful weapon ever known all at the same time. An Axis victory in World War 2 resulting in the conquest of the United States is simply a nonstarter.

Setting that aside (since we'd have no book otherwise) the Nazi feats in Castle, accomplished in just 17 years and including the colonization of Mars, Venus, the moon; as well as the damming of the Mediterranean(!) are just silly. In fact, a clever touch would have been to suggest that those feats were actually purely propaganda. They might well have been, but Dick plays it straight in the book.

Dick also seems to have not done much homework before writing Castle. The politics and depictions of Nazi characters could have been (and likely were) derived from a cursory read of Shirer's recent instant classic, Rise and Decline of the Third Reich, without much elaboration or extrapolation. Fair enough. Dick spends most of his time in the Japanese-occupied Pacific States of America, anyway, so he doesn't need to develop the German side too much.

There again, however, we have no depth. The inner monologues of the Japanese (and the most Nippophile of subjects, Childan) are distinguished mostly by Dick's eschewing of the definite article. In other words, there is no "the" and precious few pronouns. That is technically how the Japanese language works, but it's not as if those concepts don't exist – they're simply implied. Moreover, it doesn't make sense that Childan would speak and think this way. The execution is clumsy. It makes the Japanese come off as pidgin-speakers, incapable of erudition in English.

The Japanese and Easternized Americans also exhibit a painful stiffness, and utterly spartan adherence to the ancient arts and ways. It's as if Dick had read Suzuki's Zen and Japanese Culture (one of the recent wave of books the Japanese have released to rehabilitate the image Westerners have of them) and took it as representative of all Japanese culture. I've been to Japan ten times. I've studied Japanese for two decades. I have a great many Japanese friends. They are as varied as any other set of people, and this monodimensional portrayal does them no favors – nor does it interest particularly.

Add to this the sterile, detached atmosphere of the book, as if the words were cloaked in gauze, and it makes for an often sloggish read. I understand that the style underscores the bleak hopelessness of life in the new America, but there should have been some variation among the characters. They all think similarly. A sort of cynical weariness. It's even justifiable, but it's oppressive and monotonous.

The reason for Dick's long absence from the science fiction genre (alternate history is not strictly science fiction; one of Dick's characters even says as much in Castle, but let's not split hairs) is that he, like Sturgeon and many others, tried to make it big with a mainstream book. Like Sturgeon, he was not successful, so it appears he has tried to bridge the gap between SF and the mainstream by picking a particularly popular topic. Shirer and Suzuki have certainly plowed the field for Dick, and early buzz around Castle is strong.

But unlike Heinlein's mainstream success, Stranger in a Strange Land or Sturgeon's less successful (but better) Venus Plus X, I find it difficult to discern an overall message in Castle. I find myself comparing Castle unfavorably with Orwell's 1984, a book that was not only an excellent novel, but also a profound cautionary tale against Communism and the pursuit of power for power's sake. Castle doesn't really say much other than "life under the Japanese would be pretty lousy, albeit better than under the Nazis." The interesting relationships between characters, and what Dick tries to convey through them, are subverted by the lack of plausibility of Dick's alternate 1962 and by the flawed and flat portrayals of those who live in it.

Of course, maybe these flaws are intentional. The ending suggests that the world of Castle isn't even real, just some sort of half-baked flight of fancy. One might conclude that all of the stereotypes, all the shallow history, the mind-numbing sameness of the characters are just beams to support the structure of a colossal cosmic joke. That Castle really is just a Dickian daydream set to paper, and that the styling of its components is designed to underscore the unreality of the story's proceedings. Seen in this light, Castle would be subtly brilliant.

However, I suspect that gives Dick too much credit. I think Dick was really just throwing vague ideas out there and hoping we'd Rorschach them into something coherent. Castle is a readable book, a well-timed book, and it knits a number of characters together somewhat entertainingly, at times profoundly. But it's also a sensational, shallow book. An overwrought, affected book. It's not bad – Dick is never bad – but it is not the masterpiece I think many people feel it is destined to be.

Three stars and a half stars.

![[November 6, 1962] The road not taken… (Philip K. Dick's <i>The Man in the High Castle</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/book2-672x372.jpg)