by Gideon Marcus

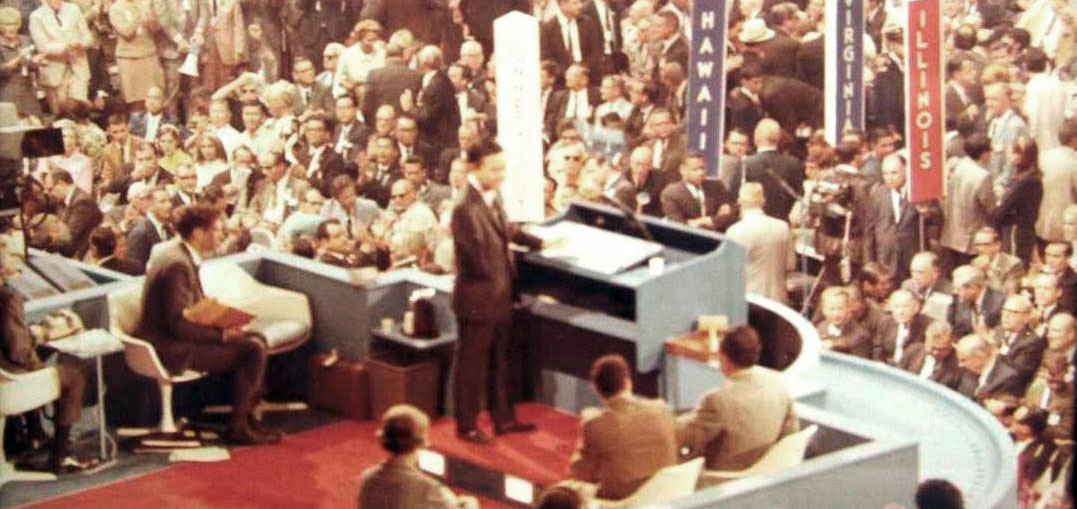

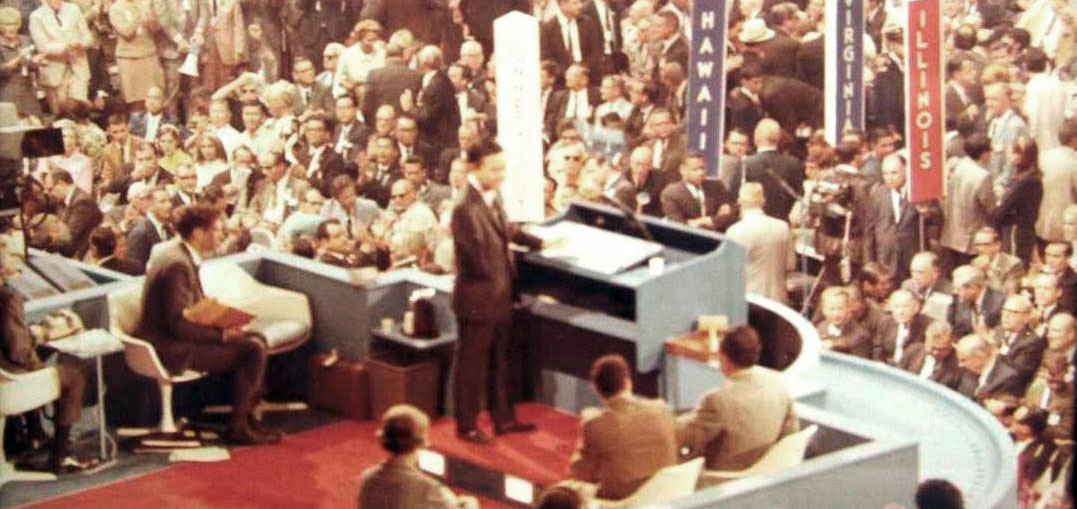

In the backround (and sometimes the foreground) of my reading of this month's issue of Analog was the Democratic National Convention held over four tumultuous days in the Windy City. This was not four days of politicians patting themselves on the back, as we saw in Miami Beach for the GOP Convention—amid the citywide busdrivers and telephone workers strike, there was tumult, walk-outs, protests, and a general breakdown of the democratic process.

Il Duce, Mayor Daley, intent on turning his town into a police state in the pursuit of Law and Order: 12,000 cops plus a contingent of National Guard were on hand last weekend.

The writing was on the wall that first day when Julian Bond arrived with his alternate set of Georgia delegates, the group that broadly represented the demographic makeup of the Georgia Democratic Party. First, they were not even allowed in; then they were grudglingly placed in the cheap seats of the balcony. All while Daniel Inouye, Senator from Hawaii, gave a stirring, unprecedented keynote speech in which he decried the anarchy and violence occurring outside the convention halls, but nevertheless put on the assembly the responsibility of rectifying the racial injustice that led to such agitation.

Eventually, the delegates prepared to vote on the certification of the Georgia delegation that had been approved by the party—the less integrated one. Actually, first they voted on if they were going to vote on it that evening. It was during this battle that the Michigan delegation offered their seats to the alternate Georgia delegation, a move that enraged members of the "official" delegation.

With regard to who was going to get the Presidential nomination, by the end of the first night, it was clear McCarthy was a dead duck, and few were mentioning McGovern. However, there was a rising "draft Kennedy" movement that peaked on Day 2 despite Ted repeatedly saying he wasn't interested. More dramatically, Day 2 marked the day police evicted 1,000 protesters from nearby Lincoln Park, CBS correspondent Dan Rather got punched by plainclothes security for not wearing his credentials prominently, dozens of delegates, mostly Black, walked out, and Georgia Governor Lester Maddox took his ball and went home, saying he was going to stump for segregationalist independent candidate, George Wallace.

Don't let the door hit you in the ass on the way out…

And that night, I'm pretty sure they still hadn't certified the Georgia delegation.

On the third day, 10,000 protesters gathered at Grant Park, a terrific anti-War demonstration broke out on the floor of the convention, and the minority position tried in vain to make an end to bombing North Vietnam a part of the party plank. By the time Humphrey was anointed the candidate (a foregone conclusion by that point), it was an anti-climax and anything but a triumphant coronation. And what a change twenty years has wrought: the Southern delegations that walked out on the convention in '48 are now behind Humphrey, where the liberals who admired the fiery populist now reject the man they view as Johnson's stooge.

Discontent was rampant. Delegates were frustrated that they were not listened to, that the motions they were voting on were not sufficiently explained, and that Mayor Daley was strong-arming them into voting the way he wanted them to. Not to mention that there wasn't enough food to feed everyone in the convention's vicinity, and the hot dogs on site were terrible. Many said 1968 marked the death of the party convention, at least in its current incarnation.

But the political strife was as nothing compared to the rivers of blood that were shed as blue-helmeted cops clashed with protestors. "The Whole World is Watching" and "Fuck LBJ" intertwined with shouts and screams, and all of it was televised in full color (but not live, as that was impossible due to the strikes and Daley's security efforts).

The only bright spot of that third evening was the nomination of D.C. and Black native son the Rev. Channing Phillips, the first American of African descent to be nominated by a major political party for President.

By the fourth day, I was exhausted, yet I tuned in anyway. I'm glad I did. That evening, the convention played a retrospective on RFK. It was too hagiographic, and frankly, the wounds too fresh to bear close watching, at least for me. But when it was over, something amazing happened. Virtually the entire audience of delegates, excluding just the groups from Texas and Illinois, rose to its feet and began clapping. Louder and louder, and then they started singing "The Battle Hymn of the Republic." Over and over, "Glory Glory Hallelujah, His truth is marching on." Daley's henchmen tried to impose order. They gaveled. They called out the Sergeants-in-Arms. Nothing deterred the delegates. All of the anger, all the discontent, all of the frustrated might-have-beens boiled over in that moment into this display of singing, of shouting, of clapping.

It was only defused when a moment of silence was called for the memory of Dr. King, and then the convention could continue. The business of the moment was the nomination of a Vice President. That morning Humphrey had already tapped Senator Edmund Muskie of Maine, and there was no serious opposition.

Yet, and in a truly touching moment, Julian Bond's name was advanced as a candidate (so, the first Black VP nominee of a major party in history), and he garnered 27 and a half votes before voluntarily withdrawing his name. Humbly, self-effacingly, he noted that he was too young to accept.

Bond withdraws his name from consideration.

Muskey and Humphrey gave their acceptance speeches that night. There was a lot on their shoulders—the need to deliver speeches that thread the needle, knitting the party back together, both addressing and condemning what had happened in Chicago.

That didn't happen. What we got was a limp flatness of platitudes. When I woke up, I learned that 20 delegates, supporters of McCarthy, had been beaten up in their hotel and arrested. The charge pelting the cops with sardines. McCarthy pointedly did not congratulate Humphrey that morning; the Vice President, now the newly christened candidate, had made no comment on the incident, tacitly endorsing it.

So that's that. HHH is our bulwark against Nixon. Muskie is his backstop. Wallace just got a shot in the arm, and I can only think that's a blow against Democratic hopes. Americans are disunited as we have not been for many decades.

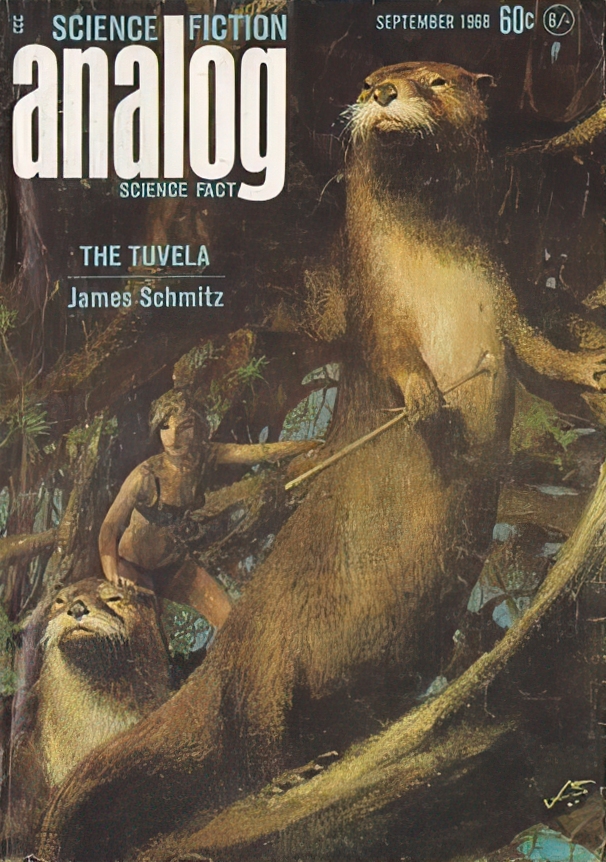

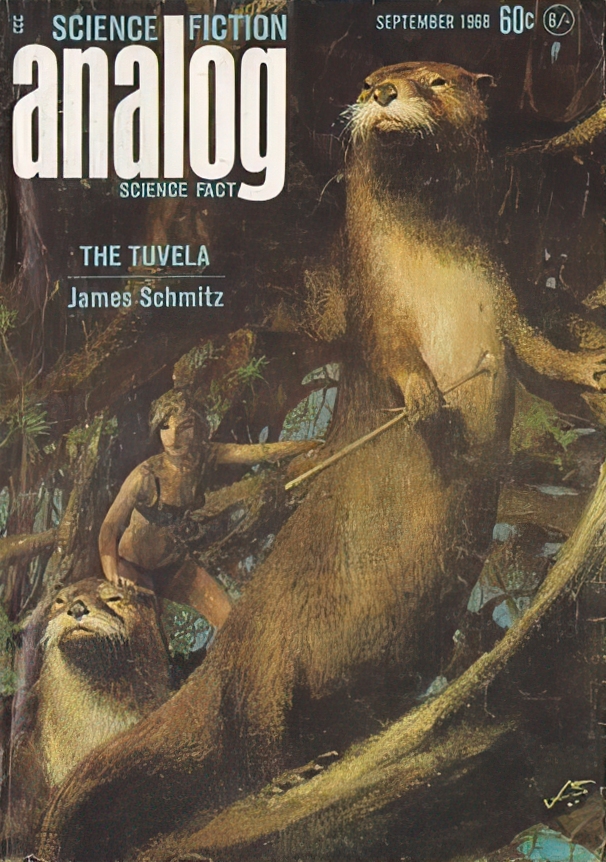

It is hard to go on with my assigned task after all that, but the job remains, and I'm the one who has to do it. The convention was four days of Hell. Accordingly, the September 1968 issue of Analog was a slog, too, though of a different kind.

by John Schoenherr

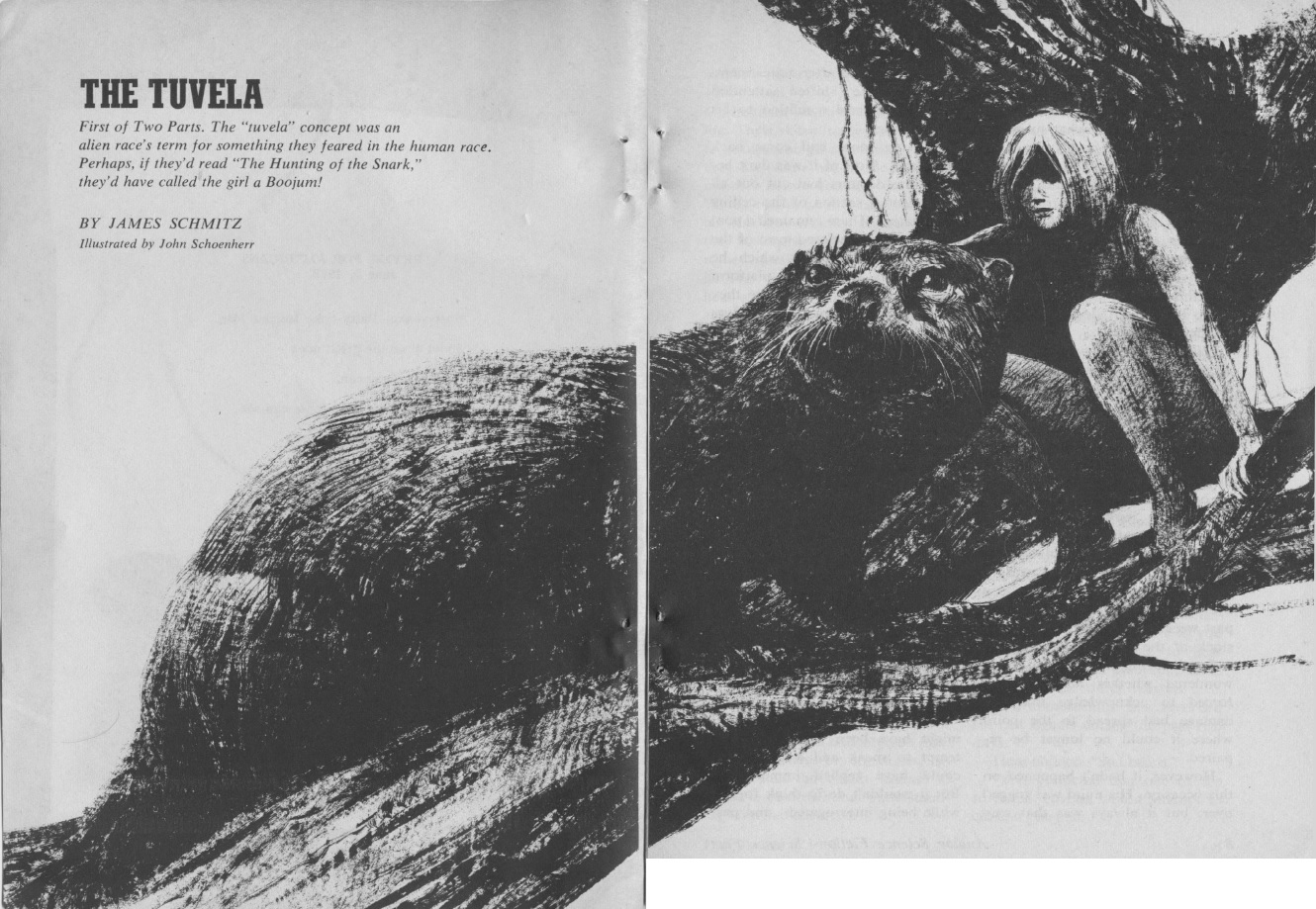

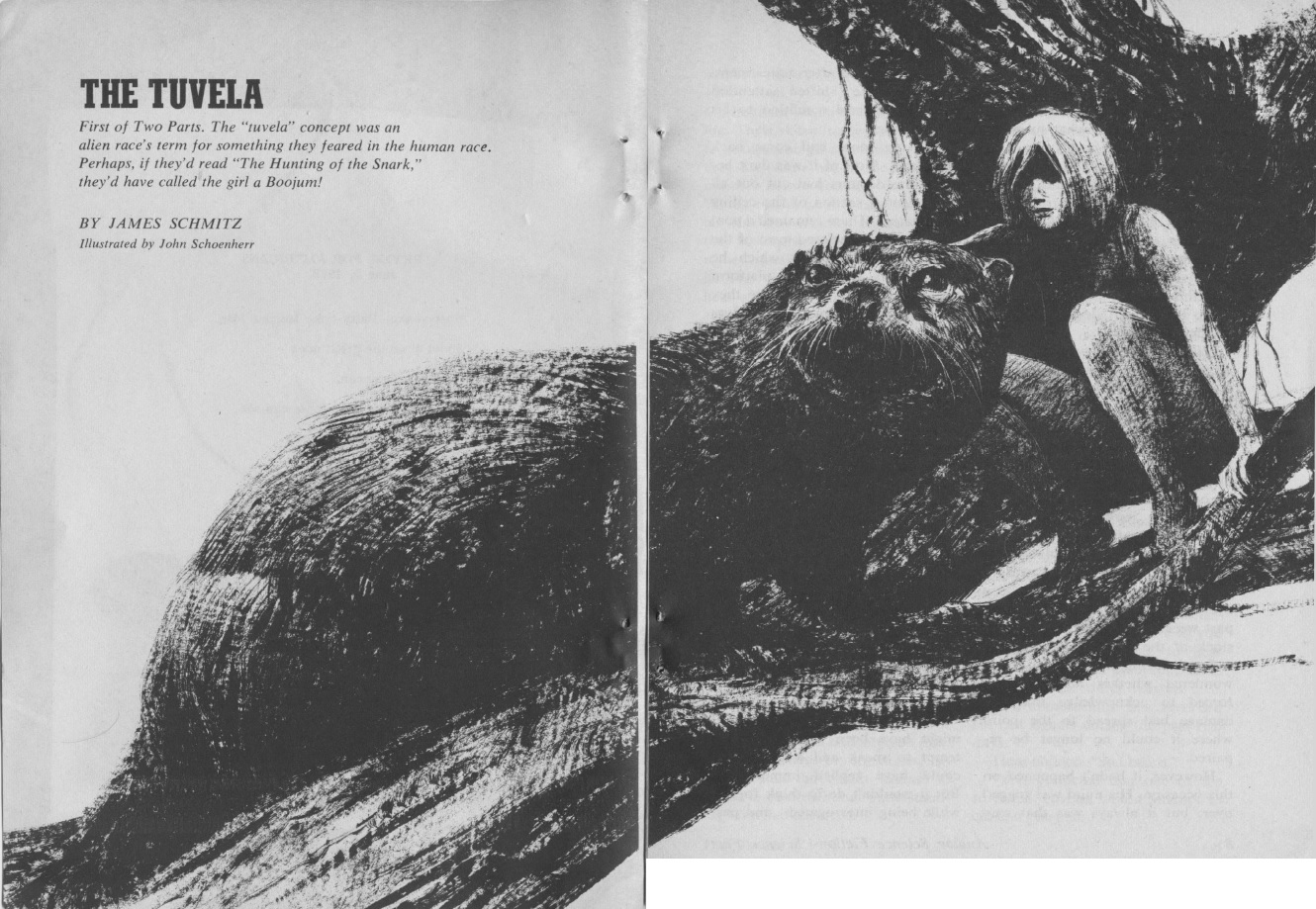

The Tuvela (Part 1 of 2), by James H. Schmitz

by John Schoenherr

The ocean planet of Nandy-Cline is in the sights of the Parahuans, a rapacious race of aliens that was beaten back by the Federation seventy years ago, and wants another try at the apple. They're being cautious. The humans beat them once, which is almost heresy to the arrogant Parahuans. To justify losing to the inferior homo sapiens, they decide there must be a secret cabal of superhumans that leads and coordinates our species. They must know more in order to sway political power from those supporting the Voice of Caution to those in favor of the Voice of Action.

To that end, they have set up a submarine base on the planet and abducted the human, Ticos Cay. Why? Because he is nearly 200 years old and seems to have found the secret of immortality. It is clear to the Parahuans that he must be in the employ of the "Tuvelas", our putative ubermenschen. They torture him, at length, but he resists because the same disciplines that have extended his life also grant him the ability to blot out pain. Nevertheless, he will succumb—unless he can get outside help.

Enter Nile Etland, a young biologist living on Nandy-Cline. She and her two giant mutant otters, sapient and clever, are looking for Cay, who has disappeared from the floating island where he was doing research. Cay's only hope is that the Parahuans will take Etland for a Tuvela and treat her with comparative kid gloves, testing her abilities, rather than killing her outright.

Etland, to her credit, is up to the challenge…

The premise for this one is excellent, and something I love about James H. Schmitz is his ability with (indeed preference for) featuring heroines over heroes. That said, the writing in this piece is often plodding and explanatory, and I found my momentum frequently flagging.

So, three stars for this installment. Now that all the pieces have been set up, perhaps the next half will be more exciting.

The Powers of Observation, by Harry Harrison

by Leo Summers

The Soviets have developed a new kind of super spy. He looks just like a man, but for some reason weighs over 400 pounds. If that leads you to guess that he's the Communist version of Hymie the robot from Get Smart, give yourself a cigar.

But the American agent tasked to pursue him through the back roads of Yugoslavia has a few gimmicks up his sleeve, too…

Well-written, but nothing spectactular. Three stars.

Steamer Time?, by Wallace West

As America grapples with its oppressive smog situation, some are calling for a return to the good ol' days—the days of the Stanley Steamer. I'm just a little too young to remember when steam cars battled internal combustion vehicles for supremacy, so I don't have the nostalgia for them that Wallace West infuses his piece with. The arguments for steam are largely that it burns clean, with its only waste gas being carbon dioxide (of course, while not strictly a "pollutant", there are other problems with it; viz. our 1958 article on the potential for industry-caused global heating). Steam engines were also more fuel-efficient, though I don't know if that's still the case.

The arguments against steam, to me, would be the long time to develop a head of steam. In the old days, waiting for your boiler to heat up was acceptable since the alternative was cranking up your IC car, and risking breaking an arm when the crank snapped back. With the invention of the electric starter, that became a non-issue. Perhaps the steam folks have a plan, too.

Anyway, the piece is readable, if a bit gushing. I'm sure the auto industry will never allow an IC competitor to emerge, although as we speak, two electric cars are racing across the nation, so who knows?

Three stars.

Hi Diddle Diddle, by Peter E. Abresch

by Leo Summers

A harried reserve USAF captain, assigned to the UFO division, gets tired of all the cranks and reporters and spins a yarn for them: the cigar-shaped "ships" are really space cows feeding on the gasses of our upper atmosphere. His creation is recounted credulously, and hysteria sweeps the nation. Eventually, even Soviet agents are involved.

But what if the captain actually guessed too close to the mark?

This is a tedious story, and it just goes on and on. Analog rarely does humor well.

Two stars.

A Flash of Darkness, by Stanley Schmidt

by Leo Summers

Mars Rover (MR) Robot is having a bit of trouble on Mars. The autonomous machine uses a holographic laser rather than a camera for navigation (apparently it's lighter; I don't buy it). When night falls, the rover finds its vision fogged and then blinded by something beyond its ken. It's up to the technicians back on Earth, and maybe a little intuition in MR Robot's mechanical brain, to solve the problem.

This could have been an interesting piece, but I felt the ending was a let-down. You'll see why.

Two stars.

Parasike, by Michael Chandler

by Leo Summers

A fellow pretending to use numerology to make guaranteed stock picks turns out to be a quack of a different duck. He is promptly recruited by America's super-secret psi corps.

A lot of talking, a lot of fatuous acceptance of psi as science—in short, the perfect Campbell story.

Two stars.

Counting off

August has been one of the roughest months of one of the roughest years in recent history. Analog finished at 2.5, which is lousy, but not that far removed from the rest: Fantasy and Science Fiction (2.5), Amazing (2.6), If (2.9). Only Galaxy finished above the three-star barrier (3.1)

You could take all the 4/5 star stuff, and you wouldn't even fill a single issue. That's awful. Women were down to their usual publication rate, producing 6.5% of all new fiction this month.

It's going to take bold new leadership to change that trend, just as it will take bold new leadership to fix the country. That new leadership doesn't seem to be near in coming. I just hope we can withstand another Long Hot Summer…

</small

</small

![[June 30, 1969] Anywhere but here (July 1969 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/690630analogcover-656x372.jpg)

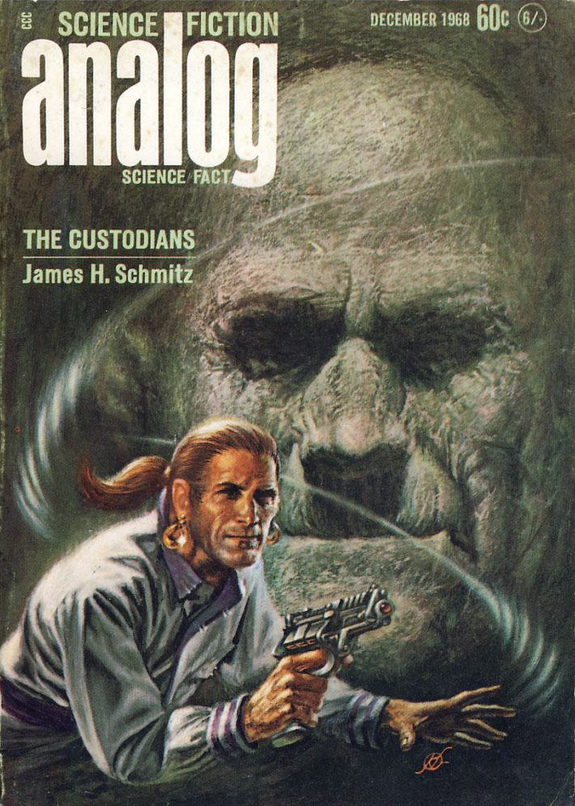

![[November 30, 1968] Up, Up, and Around! (December 1968 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/681130cover-575x372.jpg)

![[August 31, 1968] The Sound and the Fury (September 1968 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/680831cover-606x372.jpg)