[New to the Journey? Read this for a brief introduction!]

by Gideon Marcus

When you talk about destruction…

Two months ago, Jim Dunnigan started a revolution. He took over the wargame fanzine, Strategy and Tactics, and not only worked to revitalize it, he started the novel practice of releasing a new wargame in it every issue! Avalon Hill, the previous, undisputed king of the wargame publishers, comes out with one or two new games a year, whereas S&T plans to put out six to twelve (there are two in the current issue) of these magazine inserts in the same time—plus a whole line of regular releases. In fact, a number of them are already out as limited series test prototypes, which some of my friends are playing. Once they get through this round of testing, we should see some or all of them in a more finished form on our hobby store shelves.

Wow!

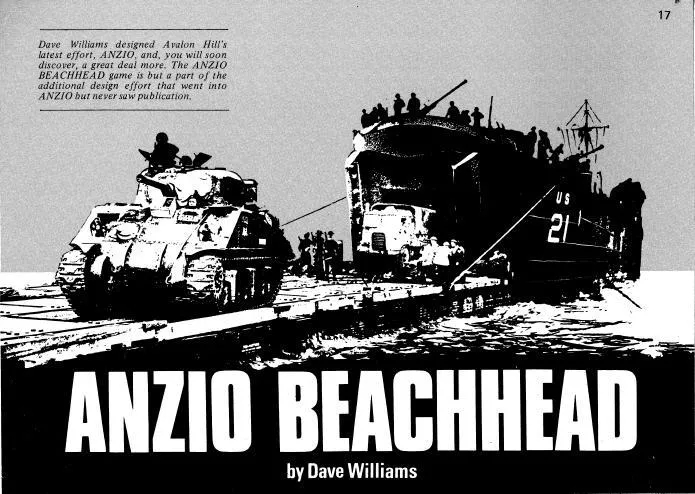

Last issue's wargame was Crete, which I was well pleased with. The two games in this issue are Bastogne, which looks very cumbersome, and a cutey called Anzio Beachhead, which we've had a lot of fun with. Let's take a look.

Reconnaissance

If the name strikes a chord, it's because we've already played a game with "Anzio" in the title—namely Anzio, which billed itself as "A Realistic Strategy Game of Forces in Italy… 1944"!

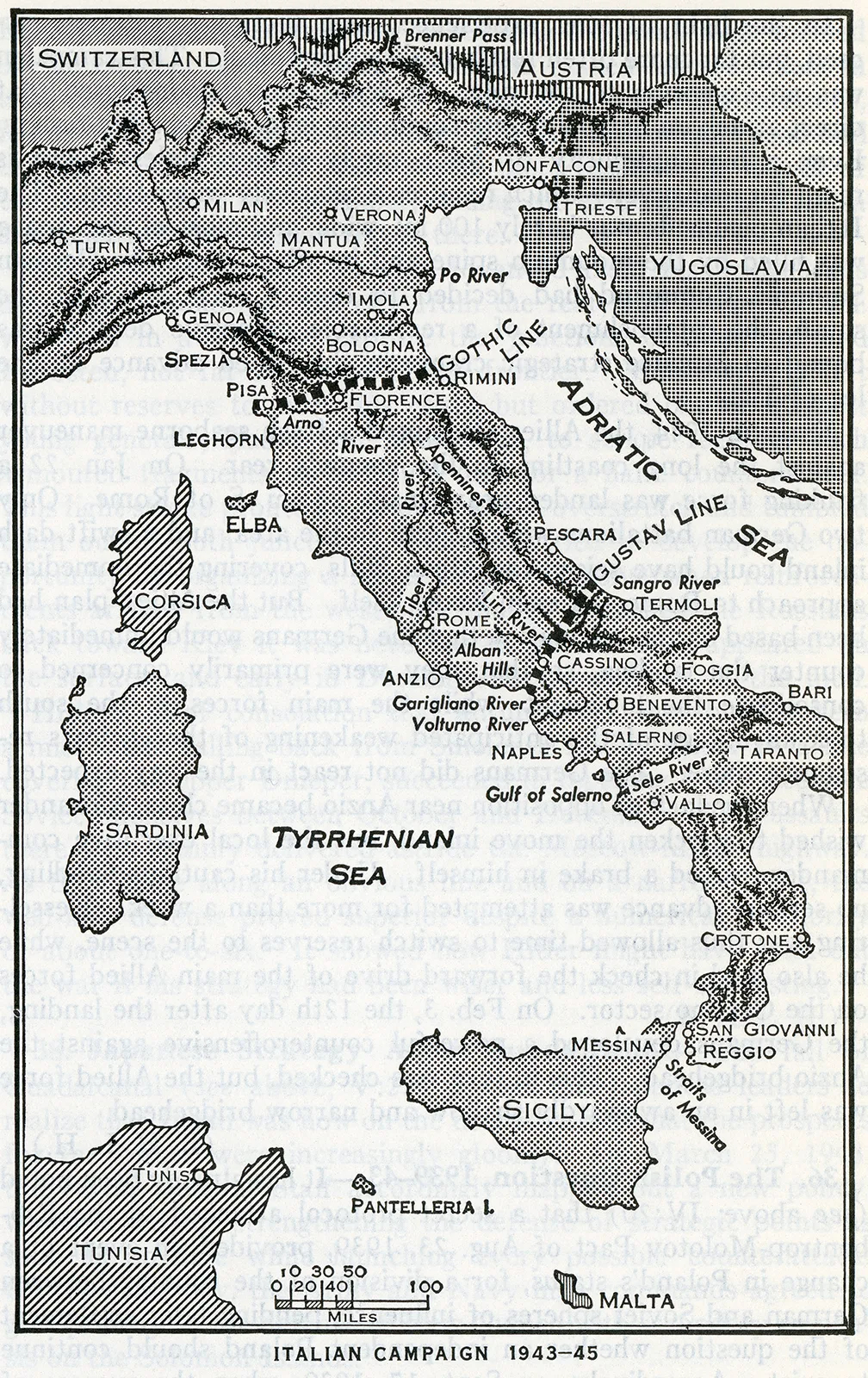

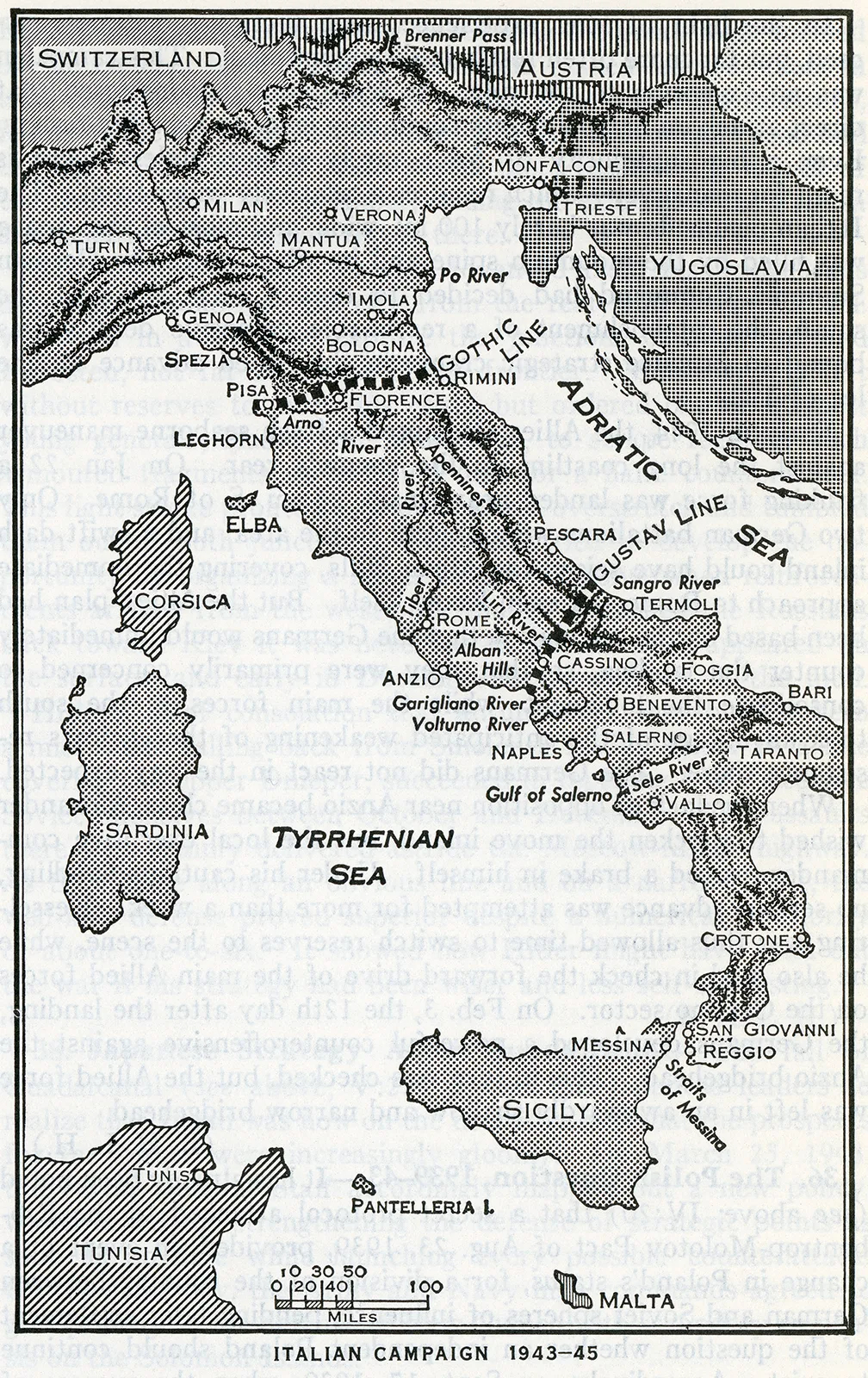

Which is funny because the game actually covers from the Salerno landings in September 1943. Anzio is a strategic game that covers the entire Italian campaign in WW2, with invasions treated very abstractly. The invasion of Anzio in January 1944 was planned as a flank of the Germany "Gustav Line", against which the Allies had stalled. The hope was that the Allies could pierce through at a weak point and destabilize the German front. Instead, the Allies were bottled up for four long months. The front didn't move again until the Allies bashed headlong into the Gustav Line, and General Mark Clark took the Anzio forces to Rome, claiming the Italian capital concurrently with the invasion of Normandy.

(This was the wrong move, strategically—by going for glory instead of providing an anvil for the Allied hammer, against which the retreating Germans would be smashed, it meant that the Italian campaign remained an agonizing meatgrinder until the end of the war.)

But that's neither here nor there. Anzio Beachhead depicts the landings and initial expansion at an operational level, covering the early part of the campaign. In fact, it's by the same fellow who designed Anzio, Dave Williams. Here's what Jim Dunnigan has to say about it:

"Anzio Beachhead was seen as another situation like the Bulge, where the attacker had a rapidly declining edge. The original American commander was not bold, and lost. So the idea with Anzio Beachhead was to explore the what if's. At that time, I had been working on designing games for about eight years (since I first discovered the Avalon Hill games.) Before that, I was always interested in the details of history, and how they were connected. Avalon Hill wargames were the first time I saw someone else thinking the same way, and doing it in a novel way. I was always building on that."

"I had been designing a similar game, called Italy, which incorporated the rest of the Italian theater, with a smaller scale map of the Anzio area (ie, two interrelated games, one strategic and the other operational). But when Dave's game came in I thought it did a better job of the Anzio section. We had come up with some of the same solutions, and his game was more compact and suitable for the magazine."

Vital Statistics

Continue reading [February 4, 1970] To Rome, with love (SPI's wargame, Anzio Beachhead) →

![[April 4, 1970] Twixt Scylla and Charybdis (S&T's <i>The Flight of the Goeben</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/700404goeben-672x243.jpg)

![[February 4, 1970] To Rome, with love (SPI's wargame, <i>Anzio Beachhead</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/700204art-672x372.jpg)