The results are in! NASA has picked its first seven astronauts, dubbed "The Mercury Seven" since they will be flying the new one-man spacecraft when it debuts for piloted missions, perhaps next year.

The newspaper mistakenly described them as "GI"s the other day, but they are, in fact the best of the best American military test pilots from all of the services except the Army. 110 candidates were winnowed to 31, and of them, 24 were sent packing (though I suspect we may see some of them in later astronaut groups).

The chosen seven are a homogeneous bunch in several ways: white, married with children, mildly Protestant, in their 30's. But they come from a variety of places and service backgrounds. In alphabetical order, we have:

The astronauts expressing confidence that they will all come back from space safe and sound; L to R: Slayton, Shepard, Schirra, Grissom, Glenn, Cooper, Carpenter

Navy Lieutenant. Malcolm "Scott" Carpenter: 33, much has been made in the local paper since he is a native, though adopted, son from Garden Grove, California. His wife registered him for the astronaut program while Scott was at sea. He has the least flight time of the astronauts, but this is more than compensated by the man's dreaminess quotient. What a hunk!

Air Force Captain Leroy "Gordo" Cooper (for those not militarily inclined, this rank is the same grade as Navy Lieutenant): 32 and a Colorado resident. He's flown the fancy new planes, including the F-102 and F-106B. Gordo speaks with an Okie drawl, but I understand he's quite a sharp tack.

Marine Lieutenant Colonel John H. Glenn: 37, from Ohio, may have the most impressive credentials. He flew 59 combat missions in World War 2, more than a hundred in Korea, and he has the highest rank of the candidates. He's also the most religious, the nicest, and (reportedly) the most abstemious. I'd put odds on this fellow getting a plum spot in the line-up.

Air Force Captain Virgil I. "Gus" Grissom: 33, from Indiana, is the youngest and shortest of the group, but he has more combat missions under his belt (in Korea) than anyone in the group but Glenn.

Navy Lieutenant Commander (between the Lieutenants/Captains and Lt. Colonel Glenn in Rank) Walter M. "Wally" Schirra: 36, from New Jersey, he's apparently the prankster of the group. He comes by his talent honestly, his father having been a stunt pilot and his mother a wing walker!

Navy Lieutenant Commander Alan B. Shepard Jr.: 35, from New Hampshire, has the most flight time but zero combat experience. He has an intense air about him suggesting he may be a leader type. He confidently declared that he expected orbital flight would be no more hazardous than testing out a new plane on Earth.

Air Force Captain Donald K. "Deke" Slayton: 35, from Wisconsin, he's got almost as much flight time as Shepard, and World War II combat experience. He has a smart, no-nonsense look about him. I suspect he'll get a good mission. He said he signed up because we'd pretty much finished exploring the Earth, and it was time to pierce the next frontier.

L to R: Grissom, Glenn, Cooper, Carpenter

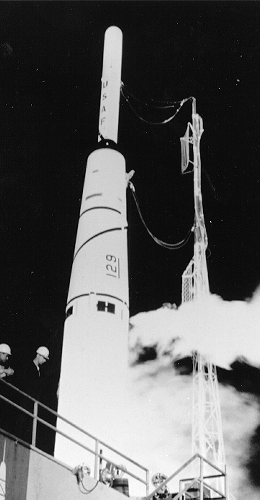

Unmanned test flights of the Mercury spacecraft, which looks a bit like a thimble, are expected to start in the summer. The capsules will be launched sub-orbitally first on "Little Joe" test rockets and then Redstones (which were used to launch the first American Explorers.

I'm willing to wager that, now that American's first spacemen have been identified, our upcoming science fiction stories will make many and copious references to them, either directly or allusive. For decades, authors have written how the first men would go into space–now they know for certain who they will be and what they will ride in (that is, unless the Soviets beat us again to the punch…)

See you in a couple of days with news of Fred Pohl's latest novella, really a short novel. It's excellent. Until then…

(Confused? Click here for an explanation as to what's really going on)

This entry was originally posted at Dreamwidth, where it has comments. Please comment here or there.