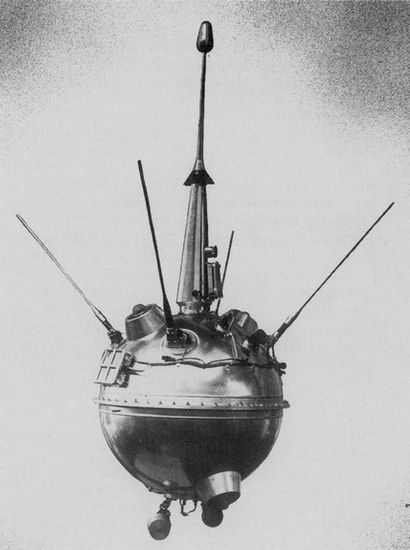

The Soviets have accomplished another space first, striking the moon with a probe yesterday, September 14, 1959, after a speedy day-and-a-half flight.

To all accounts, the mission payload was identical to Mechta, which sailed past the moon in January. I’m still not sure whether we’re to call the thing Mecha, Lunik, or Luna, but no matter the name, there’s no question but that it was an impressive feat of astrogation; the moon is actually a surprisingly small and hard target to hit. One German scientist likened it to hitting the eye of a fly with a rifle bullet at a range of six miles. And the Soviets managed to do it on their second try (that we know of).

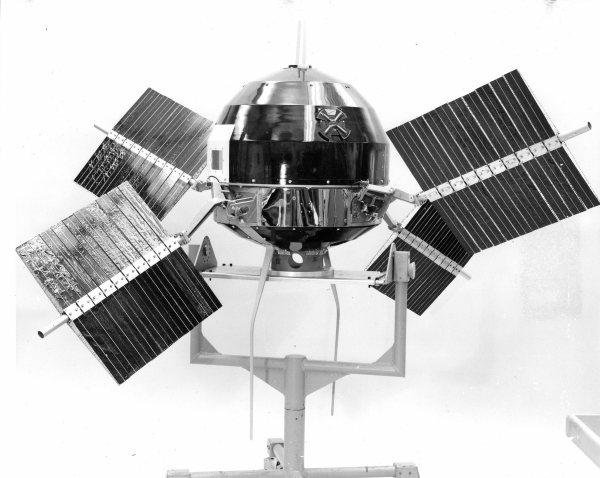

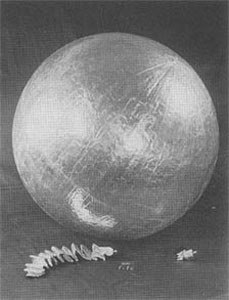

The 390kg package, much larger than anything America has tried sending to the moon so far, was packed with radiation detectors for measuring cosmic rays. It also carried a magnetometer and a micrometeoroid detector. Between the two Luniks and the three successful Pioneers, we should have a pretty good magnetic and radiation map of things this side of the moon.

Most significantly, from a political perspective, are the myriad of Soviet badges and medals that Lunik II spilled out on the lunar surface upon impact. Not only is the U.S.S.R. now the first nation to litter another celestial body, but I imagine they may start rumbling about owning the moon. After all, finders keepers!

Many have speculated that Soviet Premier Nikita Khruschev timed his visit to the United States to take advantage of the lunar shot—or perhaps it’s the other way around. Either way, it certainly gives him bragging rights as he tours our nation.

NASA has officially replied that they have a lunar probe in the works of comparable size that may go up as early as October. You’ll certainly read about it here if it does!

—

P.S. Galactic Journey is now a proud member of a constellation of interesting columns. While you're waiting for me to publish my next article, why not give one of them a read!

(Confused? Click here for an explanation as to what's really going on)

This entry was originally posted at Dreamwidth, where it has comments. Please comment here or there.