[if you’re new to the Journey, read this to see what we’re all about!]

by Gideon Marcus

The Journey has a tradition of spotlighting the accomplishments of women, both as writers of and characters in science fiction. From Dr. Martha Dane, the eminent omnilinguist who graces the Journey's masthead, to the 30+ authors who have been featured in our series on The Second Sex in SFF.

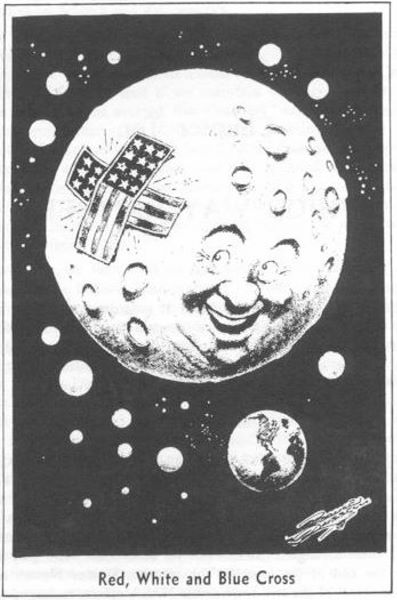

But while the Journey has covered the Space Race in lavish detail, it has devoted little space to the woman scientists and engineers involved behind the scenes. In part, this is because space travel is a new field. In part, it's because science is still a heavily male-dominated arena. While women have risen to prominence as scientists for centuries, from Émilie du Châtelet to Marie Curie to Grace Hopper, it is only very recently that they have made their way to the top ranks of space science.

Times have changed, and there is now a vanguard of women leading the charge that will perhaps someday lead to complete parity between the sexes in this, the newest frontier of science. To a significant degree, this development was spurred by the digital computer, which you'll see demonstrated in several of the entries in this article, The Woman Pioneers of Space Exploration:

Dr. Nancy Grace Roman, PhD. Astronomy

Chief of Astronomy, NASA Office of Space Science

Tennessee-born Dr. Roman began her professional career as a graduate student at Chicago's Yerkes University, then the epicenter of astronomical research. At the time, a full 20% of the students were women, and while there was no explicit discrimination against them, women earned just two thirds the pay of the men. As department chair Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar unironically observed, "We don't discriminate against women. We can just get them for less."

That hardly sat well with Dr. Roman, and she went on to the Naval Research Lab in 1955. She was initially given no assignments; in fact, she was virtually ignored. It turned out that the rest of NRL's staff (all men, of course) were prejudiced against women on account of a prior female colleague having been, as they characterized her, "useless." Dr. Roman's competence quickly disabused them of their error in projecting the failings of one person upon an entire gender.

In 1959, Dr. Roman was tapped to lead the space astronomy department at the newly formed National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), becoming the most senior woman at the agency. Dr. Roman has since augmented NASA's optical and ultraviolet astronomy efforts with new high energy and radio astronomy programs, and her fingerprints are and will be on a great many spacecraft, including the Orbiting Astronomical and Orbiting Solar Observatories, the latter of which launched earlier this year.

Marcia Neugebauer, M.S. Physics

Senior Research Scientist, Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL)

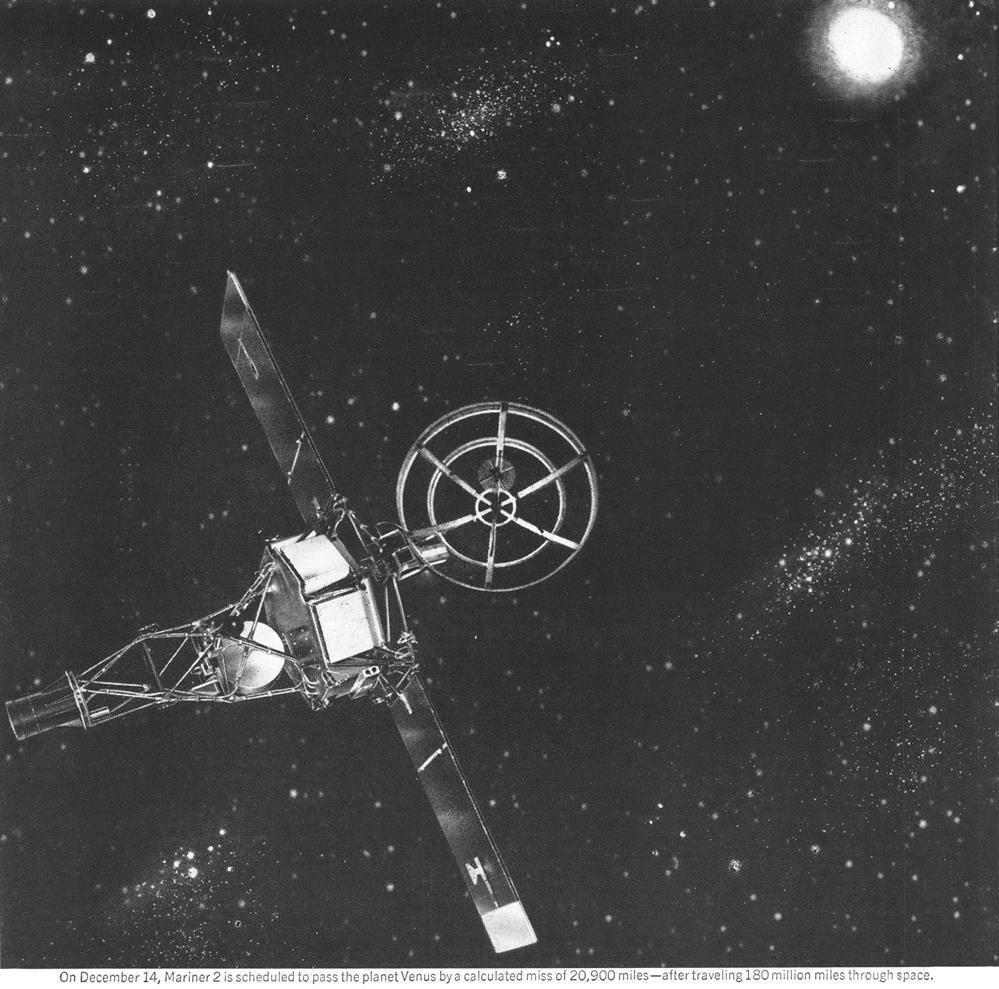

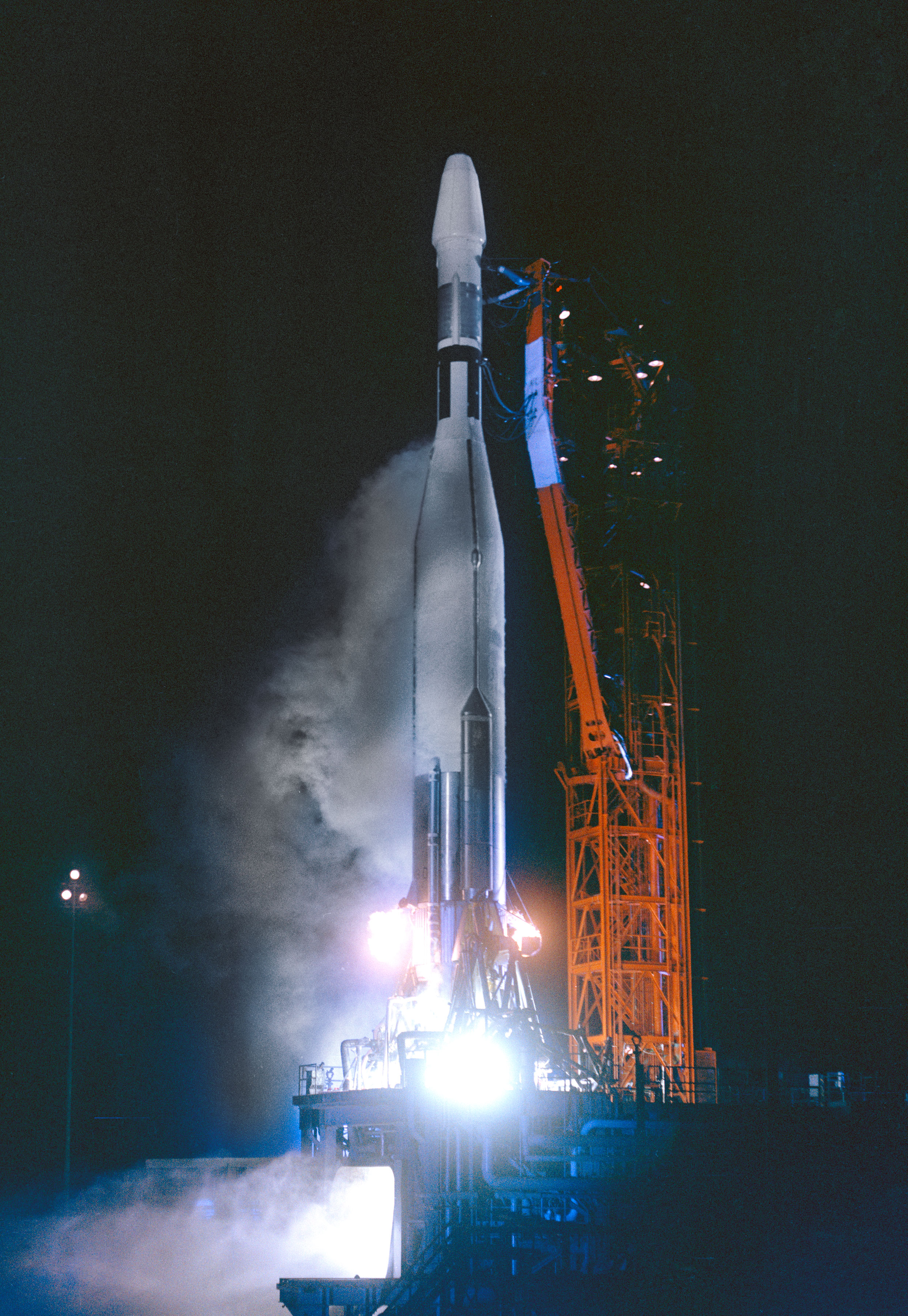

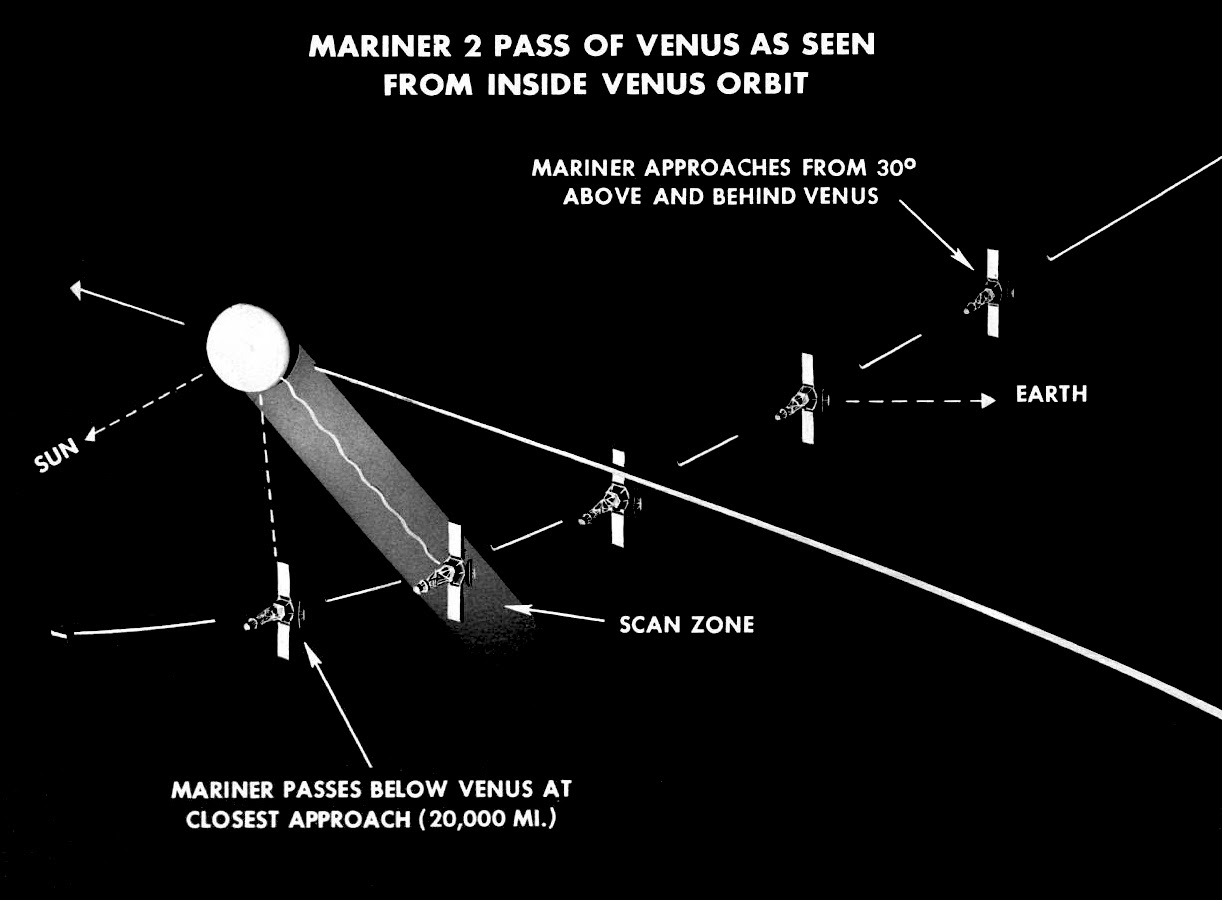

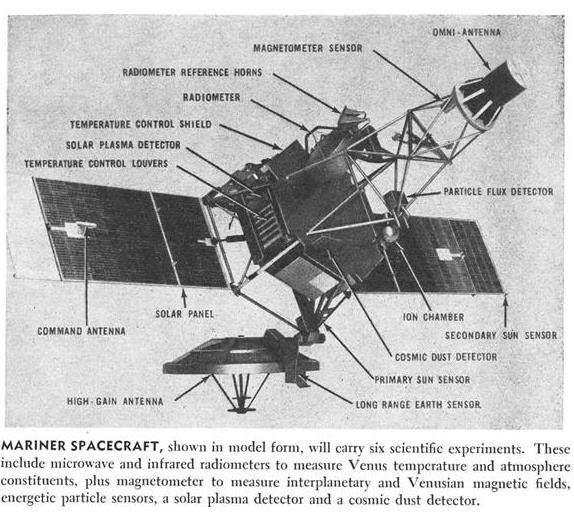

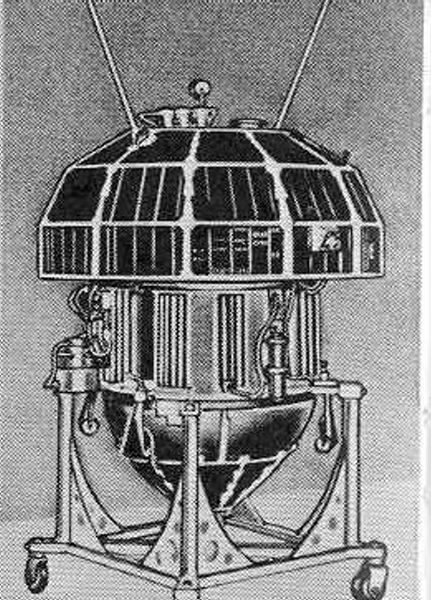

Mariner 2 is on its way to Venus, and Neugebauer is one of the principal engineers behind its construction. A graduate of Cornell and University of Illinois, Marcia came to California to marry her husband, Gerry, an infrared astronomer, taking a job as Research Scientist at JPL.

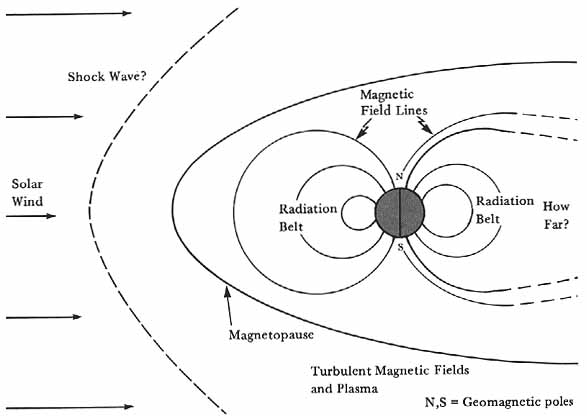

Her specialty is the solar wind, that stream charged particles issuing from the Sun whose impact on the Earth's magnetic field is profound. She was project scientist for Rangers 1 and 2, a pair of sky science flights that, sadly, were unsuccessful. But Mariner 2, which is an adaptation of the Ranger probe, also carries the plasma analyzer of Neugebauer's design, and it is now six million miles along on its journey. Whether the solar wind be found to be a gale or a gentle breeze, that determination will be thanks to Neugebauer's experiment – and one can bet that she'll have a hand in many space probes to come.

Dorothy Vaughan, B.A. Mathematics

Computer programmer, Langley Research Center, NASA

It wasn't long ago that "computer" meant a mathematician, typically female, who solved numerical problems. Companies, banks, research centers, would have a corps of computers to resolve complicated mathematical issues. NASA's precursor, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), had several such groups. One of them was the all Black, segregated West Area Computing Unit at Langley Research Center.

Vaughan joined NACA in 1943. After the War, she advanced to heading the unit, becoming the first Black manager at NACA. In 1958, NACA became NASA, and all segregated facilities, including the West Computing office, were abolished.

At the same time, human computing centers were becoming obsolete, now that digital computers like the IBM 7090 were coming into their own. But someone had to program them. Computing, even by punch-card, is still considered "women's work," as it was when it was by hand. This, then, represents an opportunity for thousands of mathematically minded women to enter a field that simply didn't exist a few years ago, a world men are keeping out of by choice: the world of digital computer programming.

Seeing the electronic computer revolution approaching, Vaughan taught herself FORTRAN, a scientific programming language, and then imparted her knowledge to her colleagues such that she and they could join NASA's new Analysis and Computation Division as coders. Dorothy Vaughan is still there, currently working on programming the Scout, a cheap and reliable solid-fuel booster.

Katherine Johnson, B.S. Mathematics and French

Mathematician, Langley Research Center, NASA

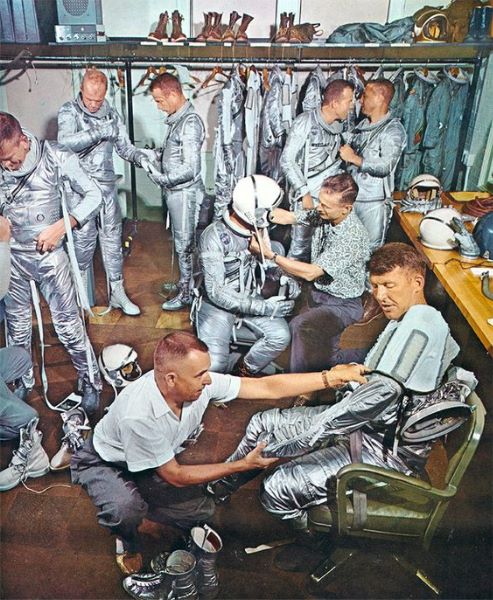

One of Dorothy Vaughan's staff was mathematician Katherine Johnson. A West Area computer from 1953, she went on to the Flight Research Division (FRD) after NASA was formed, where she became (and is) deeply involved in the Mercury manned space program.

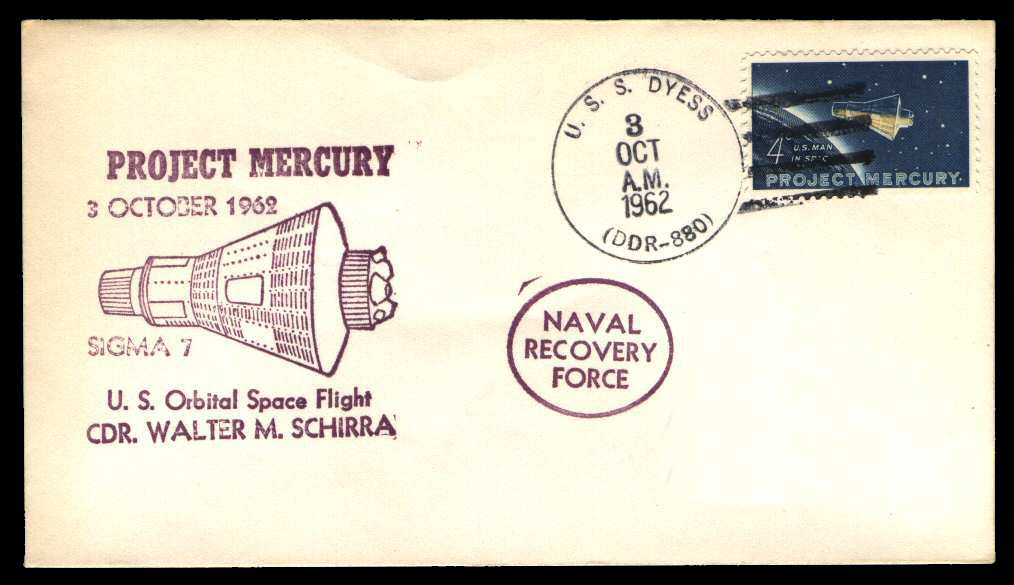

In 1960, she became the first woman at FRD to receive credit as coauthor of a research report: "Determination of Azimuth Angle at Burnout for Placing a Satellite Over a Selected Earth Position," which lay out the equations for landing an orbital spacecraft. She also did trajectory analysis for America’s first human spaceflight, the suborbital mission of Alan Shepard.

Having thus developed a strong reputation for accuracy, it is little surprise that, on the eve of John Glenn's orbital flight, the astronaut specifically requested that Johnson hand-check his trajectory equations – even though they had been calculated by NASA's most advanced computers. “If she says they’re good,” Glenn said, “then I’m ready to go.”

They were, and he was.

Mary Jackson, B.A. Mathematics

Aeronautical Engineer, Langley Research Center, NASA

Mary Jackson is not precisely a space pioneer, as her work is focused chiefly on wind tunnels and testing the aerodynamic properties of aircraft designs. Nevertheless, she is noteworthy for being possibly the only Black woman aeronautical engineer in her field, and for her remarkable story:

Originally a math teacher with a dual degree in Math and Physical Sciences, she ended up in at Langley’s segregated West Area Computing section in 1951, reporting to Dorothy Vaughan.

Just two years later, she received an offer to work for engineer Kazimierz Czarnecki in the 60,000 horsepower Supersonic Pressure Tunnel. Jackson took the job and proved herself, earning Czarnecki's endorsement to take graduate level math and physics classes offered by the University of Virginia. But the classes were held at the segregated, all White, Hampton High School. Mary had to fight for special permission from the City of Hampton to take the classes. She succeeded and in 1958, thus became NASA’s first black female engineer. That same year, she co-authored her first report: "Effects of Nose Angle and Mach Number on Transition on Cones at Supersonic Speeds."

Susan Finley

Computer Programmer, Jet Propulsion Laboratory

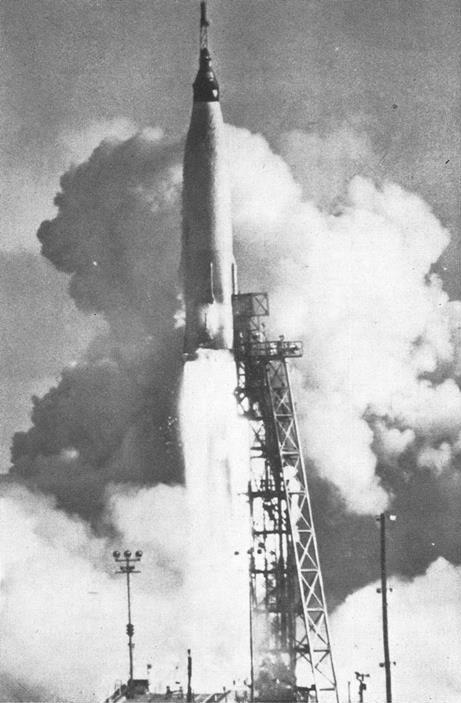

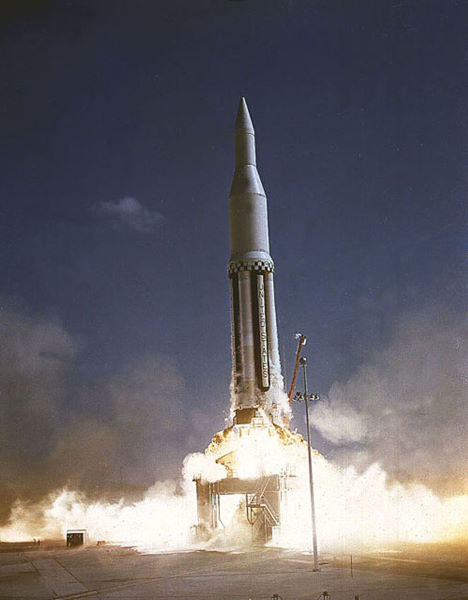

Like Dorothy Vaughan, Southern California-based Susan Finley started out as a computer. Actually, she started out as an art student, but she dropped out after her third year. Applying for a typist job at Convair, creator of the Atlas rocket that boosted Glenn to orbit, she was asked if she liked math. She did, and so was offered a computing position.

Marriage complicated things logistically, Finley moving with her husband for his job to San Gabriel. This put her within commuting distance of JPL, which she joined in January 28, 1958 – just three days before America entered the Space Race with Explorer I. In 1960, her husband went to grad school in Riverside, and Finley had to leave her position again. She returned to JPL in 1962, but not before, like many women, she had learned FORTRAN. Finley nimbly transitioned from mechanical calculators to advanced digital computers.

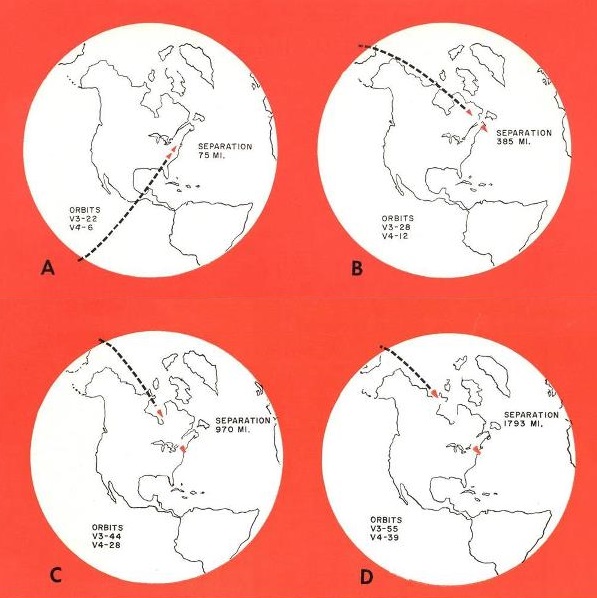

Ironically, Finley's calculations that determined that this year's Ranger 3 flight had missed the Moon by 22,000 miles were done by hand – the computer was off-line at the time!

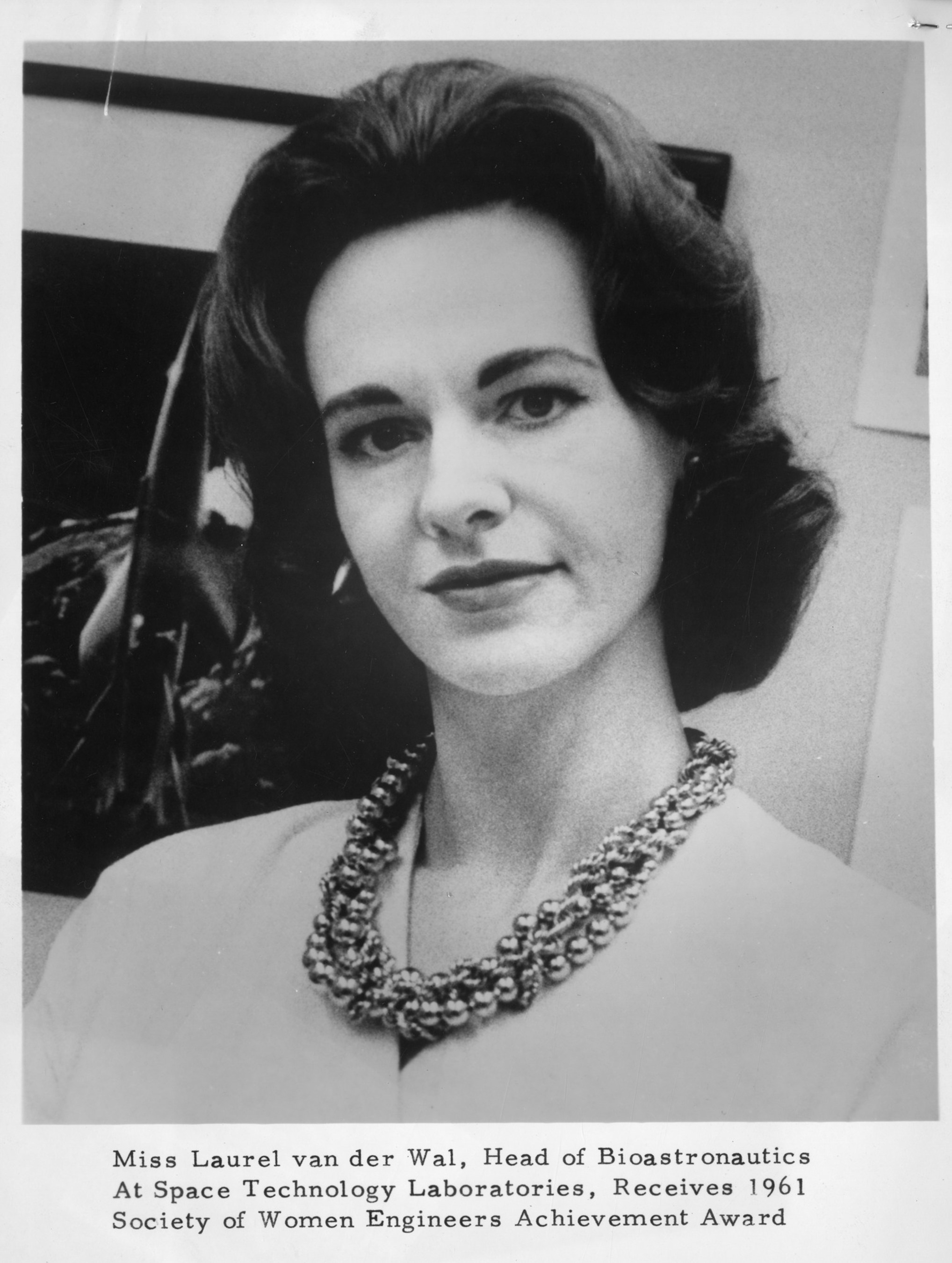

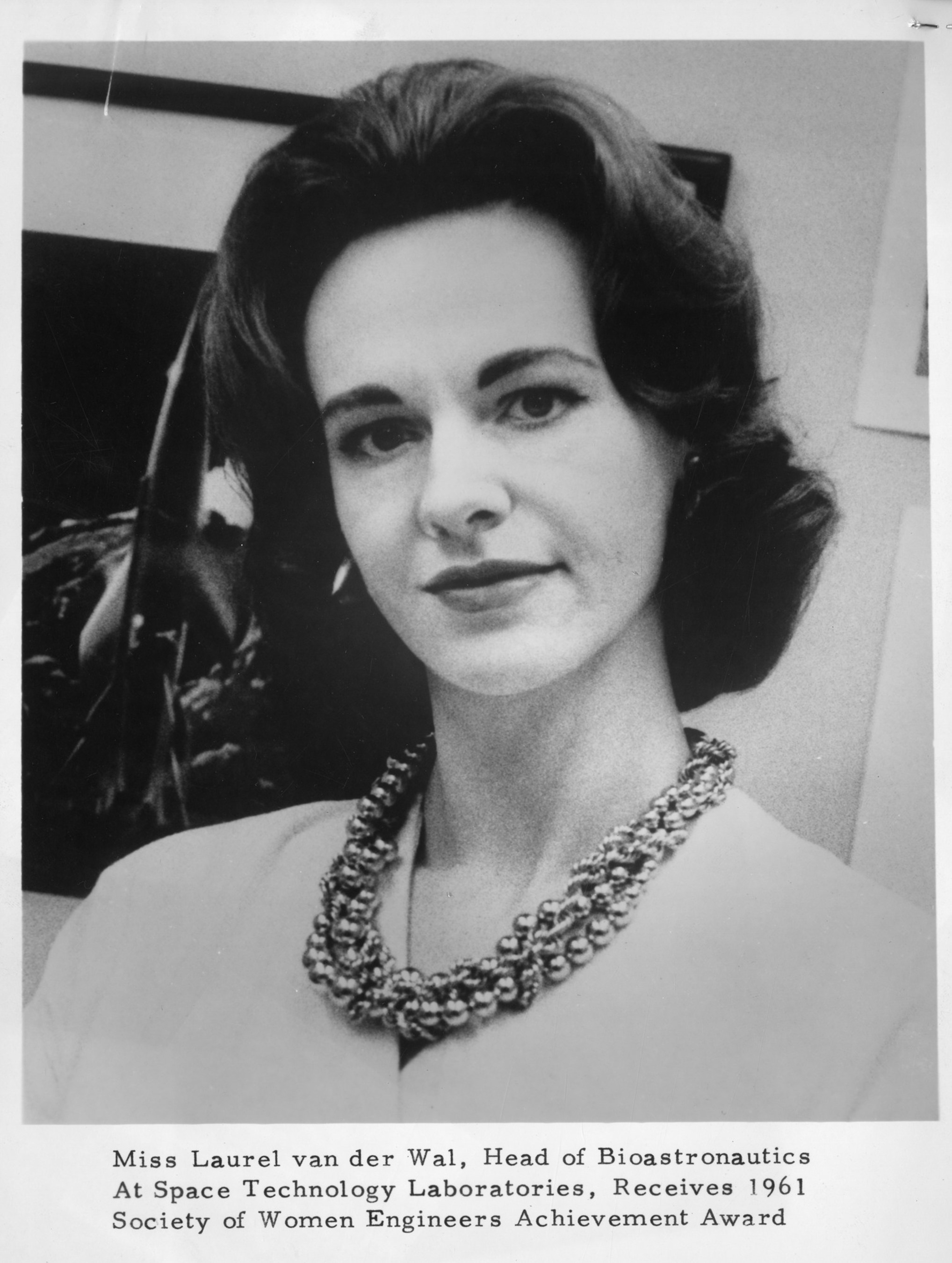

Lauren "Frankie" van der Wal, M.S. Aeronautics

Chief of Biomedicine, Space Technology Laboratories (former)

Six feet tall and tough as nails, Frankie van der Wal was project manager for the first space biological experiment. Before becoming Chief of Biomedicine at the overwhelmingly stag Los Angeles facility of Space Technology Laboratories' (STL), she had been a 15 year-old high school graduate, a model, an airplane mechanic, a deputy sheriff, a showgirl, a graduate with a Masters in Aeronautics, and much more.

In 1958, the Air Force ran a series of suborbital nosecone tests aboard the STL-designed Thor-Able booster, a rocket that had been patched together for the Pioneer Moon missions. Van der Wal abhorred a vacuum as much as nature, and she proposed using the hollow space of the nosecone to house a mouse-tro-naut. Packed into the tight space would be various biomedical monitors to track the life-signs of the rodent during its 15 minute, several thousand-mile flight (much like the ones astronauts Shepard and Grissom would later take).

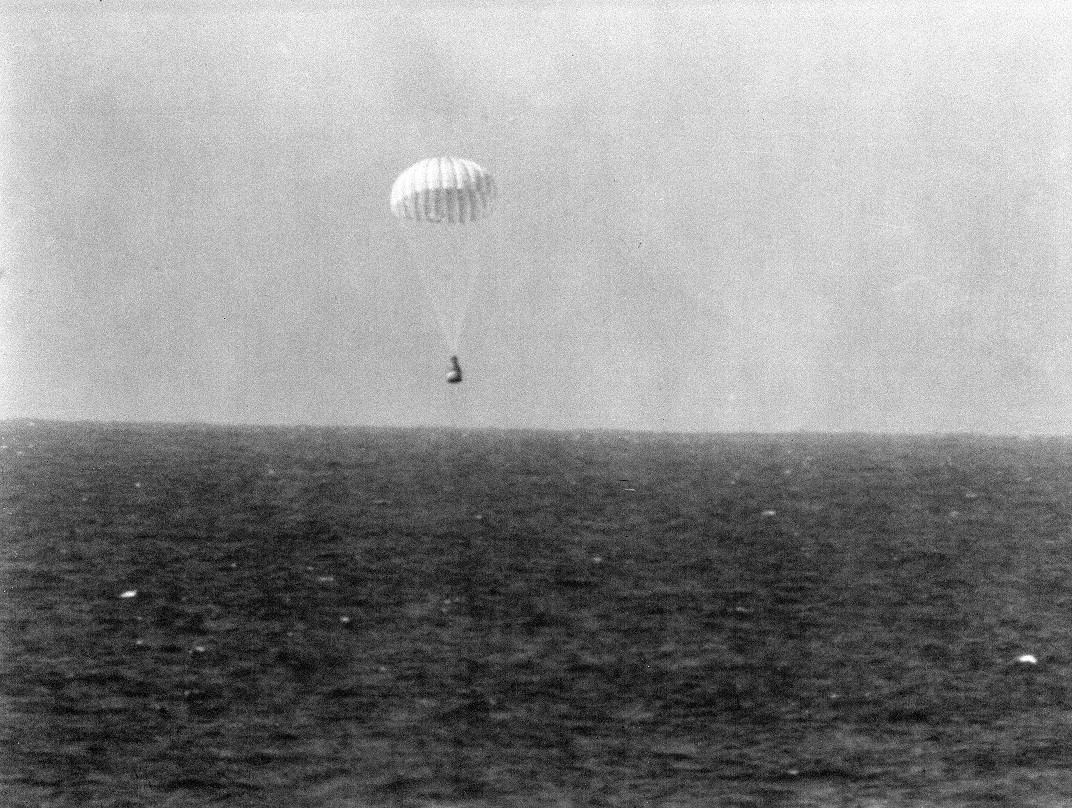

The experiment worked well, even if the mice had a penchant for biting the folks who strapped them in to their nosecone seats. The hearts of Van der Wal's mice acted like little accelerometers, hastening with the blast of the Thor engine. Sadly, none of the mice could be recovered after splashdown, but at least they proved that animals could survive the rigors of blast-off and reentry.

I understand Frankie has left STL and is recently married. Nevertheless, she set a high bar with her strong will and ability, inspiring admiring respect (and not a little fear!) in her coworkers.

These, then, are some of the more prominent of the women pioneers of space science. Their example will inspire a whole generation of woman engineers and researchers into the aeronautical sciences, and someday even into the astronautical corps. Of course, I haven't even touched upon the myriad female astronomers who are not involved with NASA or a space program, but whose contributions to science have greatly expanded our understanding of the cosmos. They'll be the subject of the next article in this series…so keep tuned to the Journey!