June was a busy month for space travel buffs, especially those who live in the Free World. Here's an omnibus edition covering all of the missions I caught wind of in the papers or the magazines:

Little lost probe

The Goddess of Love gets to keep her secrets…for now. The first probe aimed at another planet, the Soviet "Venera," flew past Venus on May 19. Unfortunately, the spacecraft developed laryngitis soon after launch and even the Big Ear at Jodrell Bank, England, was unable to clearly hear its signal.

The next favorable launch opportunity (which depends on the relative positions of Earth and Venus) will occur next summer. Expect both American and Soviet probes to launch then.

X Marks the Spot

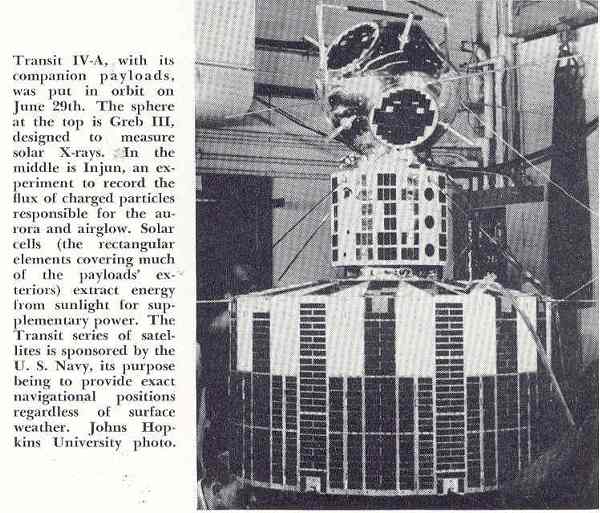

Just as planes use fixed radio beacons to determine their position, soon submarines (and people!) will be able to calculate where they are by listening to the doppler whines of whizzing satellites. Transit 4A, launched by the Navy, joined the still-functioning Transit 2 on June 29 (#3 conked out March 30, and #1's been off the air since last July).

This Transit has an all-new power source. Instead of batteries or solar panels, it gets its juice from little nuclear reactors. These aren't aren't like the big fission plants you see being established all over the country. Rather, they are powered by the heat of radioactive decay. These energy packs are small and much simpler than solar panels. Expect to see them used quite a bit on military satellites.

The Navy gets extra points for making their rocket do triple-duty: Also boosted into orbit were Injun 1 and Solrad 3. The first is another University of Iowa particle experiment from the folks who discovered the Van Allen Belt; the latter a solar x-ray observatory.

Along a dusty trail

Contrary to popular belief, outer space is not empty. There are energetic particles, clouds of dust, and little chunks of high-speed matter called micrometeorites. All of them pose hazards to orbital travel. Moreover, they offer clues as to the make-up and workings of the solar system.

Prior satellites have tried to measure just how much dirt swirls around in orbit, but the results have been vague. For instance, Explorer 8 ran into high-speed clouds of micrometeorites zooming near the Earth late last year corresponding with the annual Leonids meteor shower. Vanguard 3 encountered the same cloud in '59, around the same time. But neither could tell you precisely how many rocks they ran into; nor could previous probes.

NASA's new "S(atellite)-55" is the first probe dedicated to the investigation of micrometeorites. It carries five different experiments — a grid of wires to detect when rocks caused short circuits, a battery of gas cells that would depressurize when impacted, acoustic sounding boards…the whole megillah. It is one of those missions whose purpose is completely clear, accessible to the layman, unarguably useful.

Sadly, the first S-55, launched today from Wallops island, failed to achieve orbit when the third stage of its Scout rocket failed to ignite.

It's a shame, but not a particularly noteworthy one. The Scout is a brand new rocket. We can expect teething troubles. Every failure is instructive, and I'll put good money on the next S-55, scheduled for launch in August.

Worth the Wait

Speaking of Explorer 8, Aviation Week and Space Technology just reported the latest findings from that satellite. Now, you may be wondering how a probe that went off the air last December could still generate scientific results. You have to understand that a satellite starts returning data almost immediately, but analysis can take years.

I'd argue that the papers that get published after a mission are far more exciting than the fiery blast of a rocket. Your mileage may vary. In any event, here's what the eighth Explorer has taught us thus far (and NASA says it'll be another six months until we process all the information it's sent!):

1) The ionized clouds that surround a metal satellite as it zooms through orbit effectively double the electrical size of the vehicle. This makes satellites bigger radar targets (and presumably increases drag).

2) We now know what causes radio blackouts: it is sunspot influence on the lower ionosphere. Solar storms create turbulence that can cut reception.

3) The most common charged element in the ionosphere is oxygen.

4) The temperature of the electrons Explorer ran into was about the same as uncharged ionospheric gas – a whopping 1800 degrees Kelvin.

This may all seem like pretty arcane information, but it tells us not just about conditions above the Earth, but the fundamental behavior of magnetic fields and charged particles on a large scale. Orbiting a satellite is like renting the biggest laboratory in the universe, creating the opportunity to dramatically expand our knowledge of science.

Air Force discovers Pacific Ocean

The 25th Discoverer satellite, a two-part vehicle designed to return a 300 pound capsule from orbit, was successfully launched June 16. Its payload was fished from the Pacific Ocean two days later, the recovery plane having failed to catch it in mid-descent. I recently got to see one of those odd-tailed Fairchild C-119 aircraft that fly those recovery missions; they're bizarre little planes, for sure.

As for the contents of the space capsules, it's generally assumed that they carry snapshots of the Soviet Union taken from orbit. This time around, however, the flyboys included some interesting experiments: three geiger tubes, some micrometeroid detectors, and a myriad of rare and common metals (presumably to see the effects of radiation upon them).

You may be wondering what happened to Discoverers 23 and 24 (the last Discoverer on which I've reported was numbered 22). The former, launched on April 8, never dropped its capsule; the latter failed to reach orbit on June 8. Unlike NASA, the Air Force gives numbers to its failed missions.

Next Mercury shots planned

Virgil I. "Gus" Grissom is set to be the next Mercury astronaut in late July. His flight will be a duplicate of Alan Shepard's 15 minute jaunt last month. If all goes well, astronaut John Glenn will fly a similar mission in September.

I don't think the Atlas is going to be ready in time this year for an orbital shot. That means there will be several tense months during which the Soviets could upstage us with yet another spectacle.