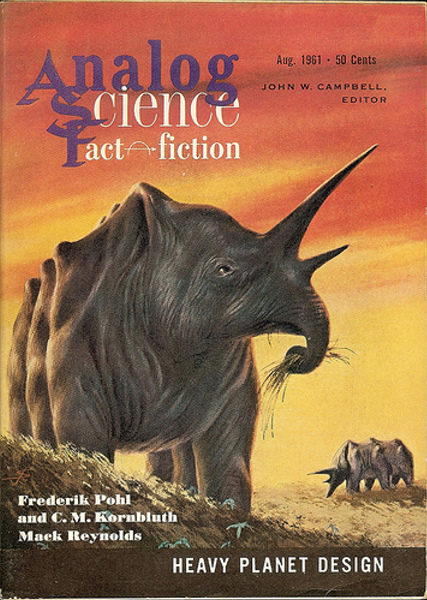

Recently, I told you about Campbell's lousy editorial in the August 1961 Analog that masqueraded as a "science-fact" column. That should have been the low point of the issue. Sadly, with one stunning exception, the magazine didn't get much better.

For instance, almost half the issue is taken up by Mack Reynold's novella, Status Quo. It's another of his future cold-war pieces, most of which have been pretty good. This one, about a revolutionary group of "weirds," who plan to topple an increasingly conformist American government by destroying all of our computerized records, isn't. It's too preachy to entertain; its protagonist, an FBI agent, is too unintelligent to enjoy (even if his dullness is intentional); the tale is too long for its pay-off. Two stars.

That said, there are some interesting ideas in there. The speculation that we will soon become over-reliant on social titles rather than individual merit, while Campbellian in its libertarian sentiment, is plausible. There is already an "old boy's club" and it matters what degrees you have and from which school you got them. It doesn't take much to imagine a future where the meritocracy is dead and nepotism rules.

And, while it's hard to imagine a paperless society, should we ever get to the point where the majority of our records only exist within the core memories of a few computers, a few revolutionaries hacking away at our central repositories of knowledge could have quite an impact, indeed!

Flamedown, by H.B. Fyfe is a forgettable short piece about a spaceman who crashes onto the surface of a Barsoomian Mars and is trailed by a lynch mob of angry Martians. There is a twist at the end, but it's a limp one. Two stars.

I don't know who Walter B. Gibson is, but his impassioned defense of psionics in our legal system, The Unwanted Evidence, is wretched. It reads like a series of newspaper clippings from the back page of the newspaper, or maybe one of those sensational books on UFOs and mystic events that are in vogue. One star.

Analog perennial Randall Garrett, an author I tend to dislike (yet one of Campbell's favored sons) gives us Hanging by a Thread, about an interplanetary ship holed by a meteor. It could have been engaging, but the smug, detached tone, and the overly technical and uninteresting solution make this a dreary read. Perhaps even Garrett knew he could do better; maybe that's why he penned this one under the name "David Gordon." Two stars.

by Douglas

Laurence Janifer also appears a lot in Analog, often paired with Garrett (either as a true duet, or just side by side). He's usually the better of the two, but Lost in Translation is a typical lousy "clever Terrans beat aliens" story, not worth your time. Again, it's pseudonymous (Larry M. Harris), perhaps on purpose. Two stars.

This is a pretty damning litany, isn't it? A series of 2-star stories and a pair of 1-star "science fact" articles. Is there any reason I don't just toss this issue into the kindling box?

There is.

Cyril Kornbluth shuffled off this mortal coil far too soon, some three years ago. He wrote a lot, both by himself and with partners. Perhaps his most famous partnership was with Fred Pohl, who now runs Galaxy and IF magazines. The Pohl/Kornbluth pair is best known for their novels, including the acclaimed The Space Merchants, but they also produced a plethora of short stories. Interestingly, many have only reached print after Kornbluth's death. I can only imagine these were skeletal affairs that Pohl has recently completed.

The Quaker Cannon, their latest piece, is very good. It's the story of First Lieutenant Kramer, a veteran of a war fought in the 1970s, between East and West. In this war, he had been captured by the Communists and subjected to complete sensory deprivation as a torture and interrogation technique. Unlike most of his captured compatriots, he neither went incurably mad nor held out until death. He simply resisted as long as he could, then he cracked and gave up what he knew. He was later repatriated.

Now 38 and still a First Lieutenant despite years of service, blacklisted from any significant role, he is suddenly recruited into Project Ripsaw: a new attempt to invade Asia. As the commanding general's aide-de-camp, he oversees Ripsaw's growth from a cadre of three to an organization of hundreds of thousands, privy to all of the unit's secrets and plans.

As the vast force prepares to invade, Kramer learns of "The Quaker Cannon," a parallel invasion unit that exists only on paper. Its purpose is to serve as a blind to confuse the enemy as to the real plan. The Soviets call this kind of deception maskirova, and it's worked time and time again.

Just prior to D-Day, Kramer is betrayed to the enemy. In short order, the Lieutenant is back in the "Blank Tank," all of his senses completely deadened. Hours pass by in seconds, each a drag on his sanity. Though Kramer's defiance is admirable, his ultimate submission, as before, is only a matter of time. He, of course, divulges the Ripsaw plan in its entirety. When Kramer returns to coherence, he is back home. Rather than being punished for his lapse, he is given a high honor.

Ripsaw was the ghost. "The Quaker Cannon" was the real invasion. Kramer's confession was all part of the plan. The story ends with that reveal.

In the hands of Randall Garrett, or even Mack Reynolds, the focus would have been on the gimmick, to the detriment of the story. Pohl and Kornbluth let Kramer be the narrator, albeit in a third person fashion. They paint a vivid portrait of a battle-fatigued soldier, almost numb to life (as though he never left the Blank Tank) until Ripsaw gives him purpose again. We are made to feel his anxiety at the thought and ultimately the reality of returning to the Blank Tank. We feel disgust at his being used as a tool, yet we also fundamentally understand why. Cannon is not a triumphant story. It is a beautifully told, weary story of a weary man, not only capturing the psyche of a battered soldier, but also the perversity of the military structure and mentality.

Hard stuff, but it deserves five stars.

So, as a whole, the issue gets just 2.2 stars. Nevertheless, thanks to that half-posthumous pair, the August 1961 Analog will be reserved a place on my shelf, not in the garbage.