December is here, and San Diego is feeling the uncommonly cold bite of near-winter weather. Why, temperatures barely make it into the upper 60s around noon-time. I'm not sure how we manage.

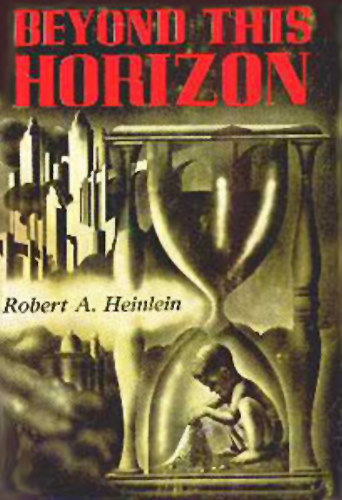

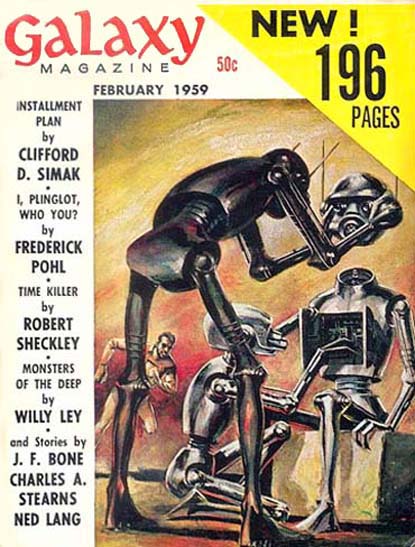

My subscription copy of F&SF never arrived. I may have to pick it up at the newsstand, if there are any left. Luckily, the February 1959 double-sized edition of Galaxy did arrive. That's how I was able to finish "Timekiller." Yesterday, while briskly walking along the beach dressed appropriately for our local sub-arctic temperatures, I finished the lead novella, "Installment Plan", by Clifford Simak. This will be the subject of today's piece.

For those who don't know Cliff, he has been a staple of science fiction for a couple of decades now. I first encountered him in 1952 with his excellent story in Galaxy, "Junkyard." Since then, he's written the serialized novel, "Ring Around the Sun," and a number of shorter stories. I like Cliff, but I find his work tends to be aimless, though completely readable. "Installment Plan" is no exception.

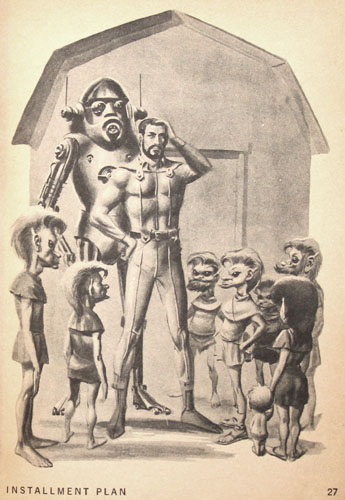

It starts out promisingly-enough with a pack of biblically-named anthropomorphic robots and their human coordinator, Steve Sheridan. They have been sent to clinch a trade deal with a race of backwards humanoids on Garson IV. The Garsonians have a cash crop that, properly distilled, produces the galaxy's most potent tranquilizer. The deal had been set up fifteen years prior by previous expeditions to the planet and then left to languish. By the time Sheridan gets to the planet, however, the natives universally refuse to deal. Thus, there is a double-mystery to solve: how did this turn of events come about, and is there any way to make a deal?

The story is interesting throughout. The problem is that it wraps up altogether too quickly and conventionally. The thoughtful tone and the careful characterization are, in my opinion, wasted. Moreover, it appears Simak is attempting to make some allegorical points, but he never quite gets there.

For instance: Sheridan's robots are portrayed as a friendly, competent, and essentially human lot. Yet, Sheridan muses, despite their abilities, and despite their being better than humans in terms of endurance and ability to learn (since their skills are banked in storage units called "transmogs"), they lack that spark necessary for independent operation. They need a man around to lead them, tell them what to do.

In other words, these beings may look like us, but their proper place is in servitude rather than self-mastery. With a proper guiding touch, we can help them accomplish what they are simply unable to do themselves. I don't think the parallel to slavery and its attendant rationalizations is accidental. Whether Simak meant his portrayal of robots to condone or condemn this mindset is not clear, however. It is never made the point of the story.

Slightly more developed is the phenomenon of the bilked aboriginal. The natives of Garson IV are portrayed as an honorable but stupid, primitive lot. They seem ripe for the cheating, which is why their being uncheatable is so frustrating and incomprehensible to Sheridan. Sheridan is further hamstrung by his government's rules that strictly prohibit the wholesale appropriation of native land or slaughter of its owners.

It ultimately turns out that the Garsonians have already been bilked–by another race. Having committed themselves, under most unfavorable terms, to this other debtor, they have nothing left to trade to the humans. Moreover, the provisions of the deal include the mass exodus of the natives from their planet, leaving it fallow for the taking.

It's an uncomfortably familiar scenario, one that has been repeated on Earth on many occasions when "civilized" men have encountered "primitives." Again, I waited for some kind of commentary from the author. Instead, Simak has Sheridan capitalize on the opportunity. With no one on the planet, the government's rules regarding non-interference are inapplicable; Sheridan plans to establish his own corporate farm and milk the planet for all its worth.

Put this way, the story sounds like satire. It is written completely without irony, however. I've said before that our cultural prejudices are the air we breathe. It takes conscious effort to take a deep whiff and catch the stink. Science fiction should be (and occasionally is) more progressive than your average literature, but too often, as happened in this story, it is simply a product of its time. In the end, Simak put some interesting and challenging ideas into this novella, and they would have made interesting stories in their own right. As is, they instead seem to tacitly condone a status quo I'm not comfortable with.

(on the other hand, at least the protagonist has a beard, and skintight clothes are available for all genders in this future!)

(Confused? Click here for an explanation as to what's really going on)

This entry was originally posted at Dreamwidth, where it has comments. Please comment here or there.