by Brian Collins

There must be a growing demand for original anthologies of science fiction, because they keep coming—both standalone titles and series. Infinity One is, going by its title, the first in yet another series of these, although notably there is one reprint between its covers (really two reprints, as you'll see), a story that many readers will already be familiar with. Robert Hoskins is an occasional author-turned-agent-turned-editor, whose high position at Lancer Books has apparently resulted in Infinity One. Will there be future installments? Does it really matter? We shall see.

The tagline for Infinity One is “a magazine of speculative fiction in book form,” which strikes me as a sequence of words only fit to come from the mouth of a clinically insane person. This is a paperback anthology and nothing more nor less. I mentioned in my review of Nova 1 last month that Harry Harrison claimed that he simply wanted to put together an anthology of “good” SF, although I’m not sure if Hoskins had even such a basic goal in mind.

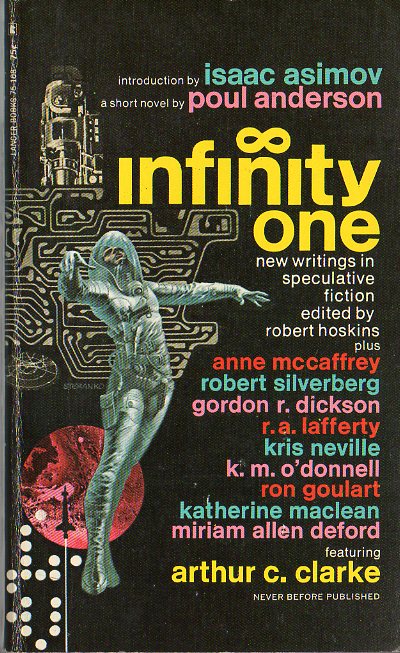

Infinity One, edited by Robert Hoskins

Continue reading [April 8, 1970] All Too Finite (Infinity One, edited by Robert Hoskins)

![[April 8, 1970] All Too Finite (<em>Infinity One</em>, edited by Robert Hoskins)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/ANCL00221-400x372.jpg)