by Jason Sacks

War is on everybody’s minds these days as the controversies around the Vietnam War rage on.

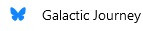

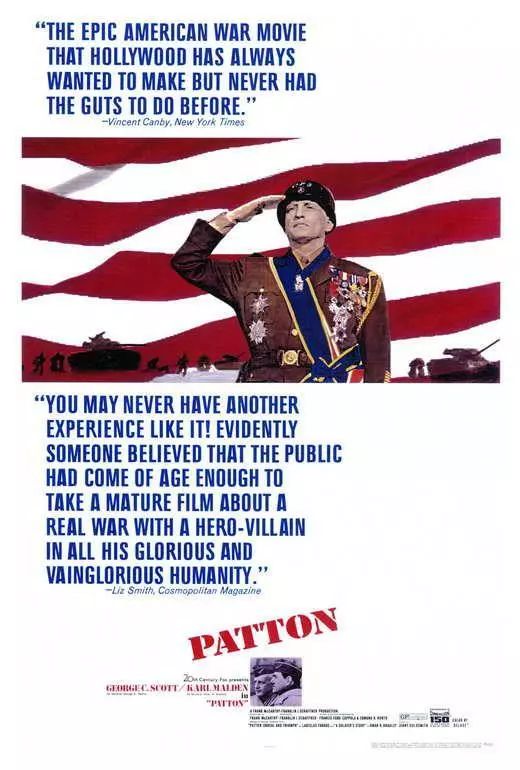

Two new films, Patton and M*A*S*H, provide complex and nuanced views of war. These two films contrast strikingly, overlapping with some ideas, but dramatically far from each other with others.

The two films also present a complete contrast in look and feel. Patton has a traditional roadhouse production look and feel. But the film isn't stiff – it celebrates the quirkiness and depth of its lead character, making it a surprisingly complex film whose revolution rests with General Patton, himself. M*A*S*H focuses on the eccentricities of its lead characters but is surprisingly conservative in terms of gender roles and expectations. In its filming and style, however, M*A*S*H is like nothing we've seen before.

Following the General

Patton, directed by Franklin J. Schaffner, stands as an epic portrayal of one of the most controversial and enigmatic military figures of World War II, General George S. Patton. The film not only delivers a stunning performance by George C. Scott but also delves into deeper themes that reflect the complexity of war and the man who seemingly thrived in it.

General George S. Patton, a larger-than-life figure with an unyielding belief in his destiny to lead and conquer, appears almost mythic in his determination and ferocity. Yet, within this portrayal, there's an underlying tragedy – Patton is depicted as a man out of his time, someone whose ideals and mannerisms belong to an era long past.

Patton: A Man Out of Time

Patton’s character is deeply rooted in the ethos of classical warfare, where personal glory and valor were the hallmarks of a military hero. He draws inspiration from historical military figures and battles, often romanticizing the past and seeing himself as a continuation of a warrior tradition. This is evident from his astounding opening speech, where he declares, "Americans love a winner and will not tolerate a loser."

Throughout the film, Patton’s anachronistic views are at odds with the modern world. His reverence for discipline, his belief in reincarnation, and his disdain for weakness are portrayed as attributes of a bygone era. In a poignant scene, he compares himself to a gladiator, reflecting his belief that he is fighting not just a modern war but a timeless battle of wills.

Patton’s rigid adherence to these antiquated ideals often puts him at odds with his contemporaries. His confrontational and abrasive leadership style contrasts sharply with the more politically astute and strategic approaches of his peers. This tension culminates in moments where his actions, though tactically brilliant, are questioned for their diplomatic and ethical implications.

General Patton at home in some Italian military ruins

General Patton at home in some Italian military ruins

Pro-War Elements in Patton

The film does not shy away from showcasing the pro-war elements that define Patton's character. His speeches and actions glorify the warrior spirit and the thrill of battle. He revels in the chaos of war, viewing the battlefield as the ultimate test of character and leadership. Patton’s relentless pursuit of victory, his insistence on pushing his troops beyond their limits, and his disdain for those who falter, all underscore a pro-war narrative that valorizes aggression and tenacity.

A significant pro-war element is the depiction of Patton’s belief in destiny and divine guidance. He sees himself as an instrument of fate, chosen to lead and conquer. This almost messianic conviction drives him to extraordinary feats of leadership, inspiring his troops to achieve seemingly impossible victories. His charisma and unwavering confidence create a sense of inevitability about his success, reinforcing the idea that war, for him, is a stage where great men prove their worth.

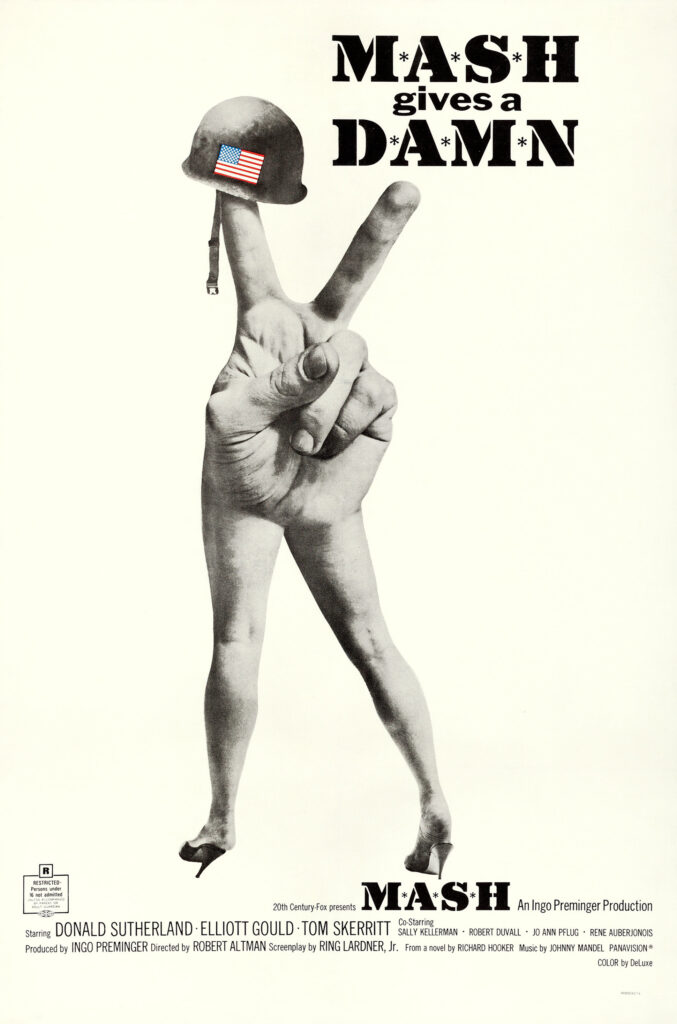

Director Schaffner with actor Scott

Director Schaffner with actor Scott

Anti-War Elements in Patton

Yet, the film is not a one-dimensional glorification of war. Director Schaffner and writers Francis Ford Coppola and Edmund H. North present a nuanced view that also highlights the anti-war elements intrinsic to Patton’s story. The personal costs of Patton’s relentless drive for victory are evident in the toll it takes on those around him. His relationships are strained, his subordinates are pushed to their breaking points, and his superiors are often exasperated by his unyielding nature.

The film also critiques the destructive consequences of Patton’s actions. His obsession with glory and his impatience often leads to reckless decisions that jeopardize lives and missions. He is a man who hates what he sees as cowardice. He refuses to believe in battle fatigue. In fact, one of the most infamous incidents in Pattton’s career – and in this film – happens when he strikes a shell-shocked soldier. Victory is the crucial goal, no matter that a victory without human honor is disgraceful.

Patton has the long view of any military adventure.

Patton has the long view of any military adventure.

Moreover, the film portrays the political and moral dilemmas of warfare. Patton’s disdain for diplomacy and his confrontational attitude often clash with the broader strategic goals of the Allies. His near-dismissal for insubordination highlights the tensions between individual heroism and collective responsibility. The film underscores the notion that war is not just a series of battles but a complex interplay of politics, ethics, and human cost.

This film’s portrayal of Patton raises important questions about the nature of leadership and the morality of war. It invites viewers to consider whether greatness in war justifies the personal and ethical compromises that come with it. Patton’s character serves as a lens through which the audience can explore the dualities of war: its capacity to elevate and destroy, to inspire and to devastate.

Patton’s presentation

Patton was filmed in a process called Dimension 150, similar to the old Todd A-O process which allowed extreme widescreen films (with a ratio of 2.25:1) to be shown with standard projectors. But as you know if you live in a big city, Patton is being marketed as a roadshow experience like The Sound of Music or Lawrence of Arabia.

Just look at that glorious widescreen image!

Just look at that glorious widescreen image!

This results in Patton having a true epic feel: battle scenes feel titanic and powerful, filled from edge to edge with soldiers struggling through the mud or firing their rifles. It’s a powerful effect, though a dramatic contrast to our national character at the dawn of this decade. This approach reinforces the “great man” feeling of George Patton as a titan astride the fights he unleashes. It also helps to make him feel like a dinosaur.

Suicide is Painless

M*A*S*H, on the other hand, feels as fresh as this week’s underground newspaper—irreverent and dismissive, full of tangents and wild moments. Patton may feel like a dinosaur, but Hawkeye, Trapper John, Painless Dentist, Nurse Hot Lips and the rest feel like people who just walked off the street in your home town.

There are acres of mud in Patton, but the world of M*A*S*H feels even muddier. Set in a military unit during the Korean War but clearly paralleling the Vietnam War, director Robert Altman delivers a film which feels like a revolution – even if its characters sometimes reinforce conservative values.

The Revolutionary Approach

M*A*S*H has rightly been celebrated for its unconventional and groundbreaking approach to filmmaking. One of the most striking features is Altman’s use of overlapping dialogue and improvisation. This technique not only adds a layer of realism but also enhances the chaotic and unpredictable nature of life in a wartime medical unit. The characters speak over each other, conversations blend together, and the audience is plunged into the midst of the chaos. Patton allows characters to make speeches. M*A*S*H doesn’t want speeches.

A word here about the script: Ring Lardner Jr. is credited as the scriptwriter, adapting Richard Hooker’s novel. As I mentioned in a recent review, Lardner was one of the Hollywood Ten, a group of screenwriters who were blacklisted by the Hollywood system for their alleged involvement with the Communist Party. It’s an act of heroism to give Lardner work today, and a great sign of the changes to American politics. I do wonder how much of this film Lardner actually scripted – M*A*S*H feels thoroughly improvised – but I welcome seeing his name again.

Appropriately, M*A*S*H shuns the typical heroic combat narrative. Instead of glorifying war, M*A*S*H presents it as absurd and grotesque. The surgeons, led by the irreverent Hawkeye Pierce (Donald Sutherland) and Trapper John (Elliott Gould), cope with the horrors of war through dark humor, practical jokes, and general insubordination. The anti-establishment sentiment that runs through the film mirrors our own countercultural movements of the 1960s, making it resonant. Patton’s insubordination is internal; the insubordination in M*A*S*H is societal.

This insubordination makes M*A*S*H feel thoroughly contemporary. Everybody hates the army, its inflexibility, command structure, even its jeeps and the terrible movies it provides to the troops. Not even the intercom works as expected (the intercom also serves as a kind of Greek chorus for the film, an unexpected bit of meta-humor). I also found the insubordination to be thoroughly hilarious.

Altman’s use of non-linear storytelling and episodic structure further sets M*A*S*H apart. The film lacks a traditional plot, instead unfolding as a series of vignettes that illustrate the day-to-day lives of the characters. This approach allows for a more nuanced and multifaceted exploration of the war’s impact on individuals, eschewing the neat resolutions and moral clarity often found in war films.

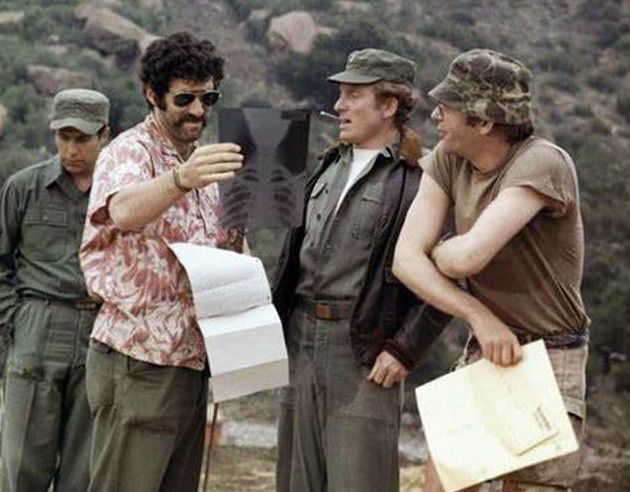

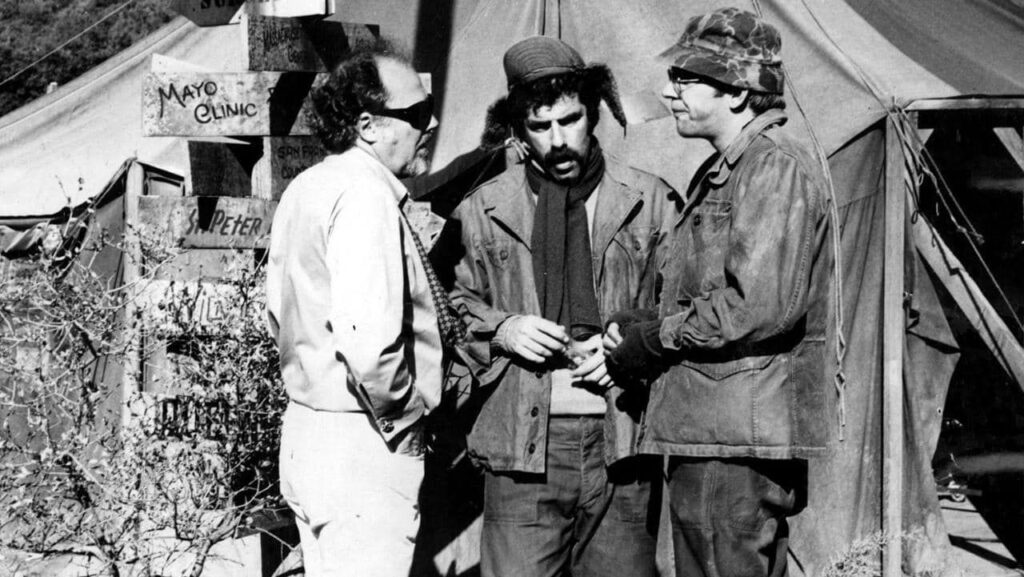

Trapper John and Hawkeye conning and confusing a helicopter pilot

Trapper John and Hawkeye conning and confusing a helicopter pilot

Individualism is at the center of everything Altman creates with his cast. None of these people are simple grunts manning their job. Instead, all the characters in the film, even those on the edges of the frame, feel like unique human beings. It even feels as if the movie could focus on those characters without sacrificing what makes this movie unique.

Revolution in Style, not Society

Despite its innovative approach, M*A*S*H is deeply conservative in its portrayal of the sexes. The film’s treatment of its female characters is troublesome. Women in M*A*S*H are largely depicted as objects of desire or sources of comic relief, reinforcing traditional gender stereotypes rather than challenging them.

Take, for example, the character of Major Margaret "Hot Lips" Houlihan, played by Sally Kellerman (Star Trek and Outer Limits). She is portrayed as a rigid, by-the-book officer who becomes the target of the male characters’ ridicule and pranks. The already-infamous shower scene, where her tent is lifted to expose her naked body to the entire camp, is a particularly glaring instance of the film’s sexist undertones. This scene is played for laughs, reducing Houlihan to a mere object of male amusement and stripping her of dignity.

The entire camp of the MASH unit mocks Major Houlihan

The entire camp of the MASH unit mocks Major Houlihan

Furthermore, the film’s male characters frequently objectify and demean their female counterparts. Nurse Lt. Dish, for instance, is referred to more by her physical attributes than by her professional capabilities. The interactions between male and female characters often revolve around sexual innuendo or outright harassment, reflecting a chauvinistic attitude all too common in both the military and society then (and, of course, now).

This presents an interesting paradox for director Altman. Many reviewers rightly lauded Altman for his complex and nuanced portrayal of a female lead in his previous film, That Cold Day in the Park. M*A*S*H critiques many aspects of military life and the absurdity of war but does little to challenge the status quo regarding gender dynamics.

The only defense I can muster to that attack is to note how M*A*S*H shows a mostly male world at the hospital. Nearly all the officers are men, and all the injured are all men. Therefore, a male attitude prevailed at camp. M*A*S*H takes place in the early 1950s, when women had recently been sent back from factories and battlefields to the kitchen and motherhood. It was a conservative era in terms of gender roles, and male chauvinism was pervasive. Surely M*A*S*H would feel strange if women, even well-trained nurses, were treated as equals.

Col. Blake is the only one who treats Houlihan as even slightly equal to him – but he is an ineffectual goof.

Col. Blake is the only one who treats Houlihan as even slightly equal to him – but he is an ineffectual goof.

The film’s humor, often at the expense of its female characters, underscores a broader societal acceptance of sexist behavior. In this sense, M*A*S*H may be revolutionary in its approach to storytelling and its anti-war message, but it remains entrenched in conservative views on gender roles.

Which is the conservative film?

M*A*S*H is a reminder of the limitations of our era’s progressive movement. While the film challenges many societal norms and offered a fresh perspective on war, it offers a discordant view in its representation of women, reflecting the broader struggles of the feminist movement as we enter the 1970s.

In fact, I adore M*A*S*H. I walked out of the theatre on an emotional high from seeing the film much like the high I get after seeing a great rock concert (I still think about that Blind Faith/Delaney & Bonnie show at the Seattle Center Coliseum last fall!) M*A*S*H feels like the revolution. It feels like the future. It feels like a new generation of film and I can’t wait to see what Robert Altman delivers next.

Altman directing Gould and Sutherland

Altman directing Gould and Sutherland

But Patton was also a movie that really shook me, particularly the oddly naïve ways General Patton strove for glory. General Patton may have been a figure from my parents’ generation, but his attitudes and life philosophy were surprisingly nuanced in the hands of George C. Scott, Franklin J. Schaffner and the writers.

The characters in M*A*S*H could come of the streets of any American town. George Patton was one of those men who seemed like he could only succeed in war.

Both films provided me experiences I’ve never had before in a movie theatre.

Five stars for each.

[New to the Journey? Read this for a brief introduction!]

![[January 24, 1970] War: Individualism and Insubordination (<i>Patton</i> and <i>M*A*S*H</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/700124movies-672x372.jpg)