by John Boston

. . . Amazing has become a normal science fiction magazine. (Stop snickering.) It’s been moving in that direction, but this November issue’s editorial says: “Beginning this issue, our old policy of reprints has been thrown out the window. . . . We will be publishing one, and only one classic story in each issue, and it will be a bonus to the fully new contents of the magazine.” Or, as the cover blurb puts it, “ALL NEW STORIES plus a Famous Classic.”

by Johnny Bruck

That phrase may seem oxymoronic, but here’s how editor White figures it: the magazine, with its new, smaller typefaces allowing more wordage, now contains about 70,000 words of new material, plus another 15,000 words, making a total per issue greater than any of the other SF magazines and allowing him to call the remaining reprints bonuses. Thus the booster’s reach exceeds the mathematician’s grasp, but I’m not complaining.

Promotion aside, congratulations to White for finally prying publisher Sol Cohen loose from his prolonged insistence on filling as much as half the magazine with reprints of (euphemistically) uneven quality. White says he “cannot truly say it was a result of my actions alone”—presumably meaning Cohen had been softened up by the complaints of his predecessors—but good for him for finally getting it done.

So what we have here are one quite long serial installment, a novelet, and two short stories, plus a reprinted short story from 1942, all new, as well as the usual complement of features. As promised last month, there is a science article by Greg Benford and David Book, and as then implied, Dr. Leon E. Stover is conspicuous by his absence, and not missed.

A book review column, shorter than usual but just as vehement, features editor White’s praise of Lee Hoffman’s The Caves of Karst and a new reviewer, Richard Delap, whaling on Bug Jack Barron: “Science fiction’s answer to Valley of the Dolls has now made the scene with all the pseudo-values of its mainstream counterpart unrevised and intact in a transposition to pseudo-sf.” Delap also doesn’t care much for the new collection of old stories The Far-Out Worlds of A.E. van Vogt, but this disappointment is expressed more in sorrow than in gusto. These two reviews are reprinted from a fanzine, but Delap will be contributing regularly to this column going forward.

The fanzine reviews and letter column fill out the issue. In the letter column, White notes that James Blish has moved to England and his book reviews will be less frequent. Other highlights of the letter column include Joe L. Hensley complaining in kind about the misspelling of his name on last issue’s cover, Bob Tucker reviving his 36-year-old beef about staples, to White’s consternation, and both White and John D. Berry, the fanzine reviewer, weighing in on the purpose of that column in response to a complaining reader. White takes issue with a reader who thinks the use of “sci-fi” is only a minor problem, and announces to another reader that he has dropped the movie reviews for the present. He also notes that he continues to write stories but his agent insists on sending them to Playboy—where, I note, nothing by White seems yet to have appeared.

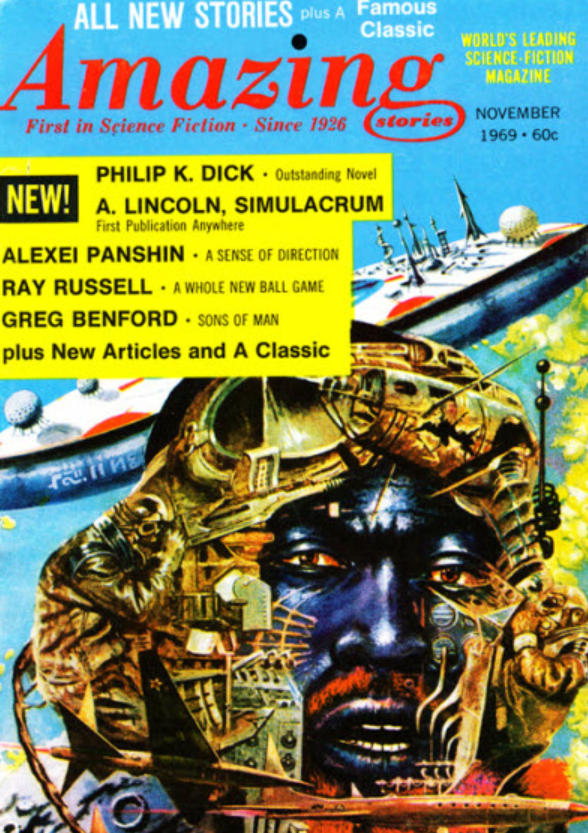

Oh, the cover. I almost forgot. It’s the good cover by Johnny Bruck that we’ve been waiting for—not especially attractive, but very interesting. Foregrounded is an African-looking face peering out from what at first looks like the fur-lined hood of one of the Inuit or other far-North American peoples, but on closer examination is a collage of partial images of pieces of equipment and (I think) living things. It’s a surreal picture that, unusually, doesn’t look like imitation Richard Powers. Provenance is the German Perry Rhodan #250, from 1966.

On the contents page, Greg Benford’s story Sons of Man is listed as “The story behind the cover.” White said last issue that he doesn’t have control over the covers, but he’s been able to commission stories, including Benford’s, to be written around the pre-purchased covers. So I guess Sons of Man is actually the story in front of the cover. Inside, the story is illustrated by none other than editor White—his first professionally published art. It’s adequate, but he shouldn’t quit his day job. In other interior illustration news, Mike Hinge has done small illustrations for the headings of the editorial, book reviews, and other departments.

A. Lincoln, Simulacrum (Part 1 of 2), by Philip K. Dick

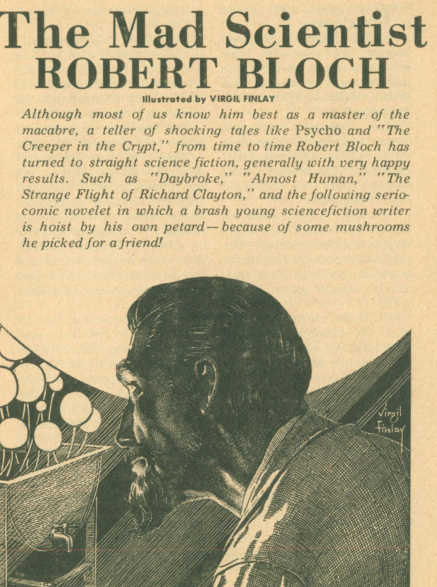

The biggest news in this issue is Philip K. Dick’s serial, A. Lincoln, Simulacrum. Per my practice, I won’t read and rate this until both installments are available, but there’s plenty of talk about the novel here. White’s editorial says without elaboration that it is totally uncut—in fact, it’s “slightly revised and expanded” for its appearance here.

by Mike Hinge

White does leave us with a bizarre anecdote. Several years ago, he showed Dick a photo of himself looking rather like Dick (both with full beards and dark-rimmed glasses). Dick asked for a copy, since his agent was after him to provide a photo for a British edition of The Man in the High Castle. So Dick sent the photo of White—and it appeared on the book. White says: “So here’s a chance to say, ‘Thanks, Phil,’ for the chance to associate myself, albeit deceitfully, with one of his best books.”

About the novel, White says:

“. . . Phil told me, ‘I put a lot of myself into this one—I really sweated into it.’ It’s more of a novel of character than any previous Philip K. Dick novel, and in writing and scene construction it approaches the so-called ‘mainstream’ novel. It is also something of a ‘root’ novel, planting as it does in 1981 many of the themes and constructs which pop up in later books of his loose-limned future history. And it is the first and only Philip K. Dick novel to be told in first person by its protagonist.”

Sons of Man, by Greg Benford

by Ted White

Greg Benford’s Sons of Man is a well crafted story using the familiar device of telling two unrelated stories in parallel, gradually revealing that they are not so unrelated after all. In one, Livingstone, who has moved to the northwestern wilderness to get away from civilization, finds a man named King collapsed in the snow near his cabin with severe burn injuries of no obvious origin, then sees a face peering into his window, and later, bare footprints two feet long. King’s been Sasquatch hunting and they seem to be hunting him back.

Meanwhile, on the Moon, Terry Wilk is trying to make sense of the records of an ancient spacecraft that crashed after visiting Earth early in human prehistory. Members of the New Sons of God cult are looking over his shoulder to make sure he doesn’t find out anything heretical. The story reads like it might develop into a series but stands on its own. The style seems a little awkward at the beginning, as if it’s something Benford started earlier in his career and came back to later, but overall, it’s very readable, cleverly assembled, and generally enjoyable. Four stars.

A Sense of Direction, by Alexei Panshin

Alexei Panshin’s short story A Sense of Direction is set in the same universe of “the Ships” as his Nebula-winning Rite of Passage. The interstellar Ships lord it over the people of the colonies that they established. Arpad, whose father married into a planetary culture and left (was left by) his Ship, was reclaimed for the Ship when his father died. He’s miserable in its unfamiliar culture, and makes a break for it during a landing on another planet. But the folkways there are so bizarre and repellent that he quickly changes his mind and sneaks back. So, like most of Panshin’s work, it’s Heinleinian: The (Young) Man Who Learned Better, capably done but just a bit too schematic and pat. Three stars.

A Whole New Ballgame, by Ray Russell

Ray Russell contributes A Whole New Ballgame, a compressed soliloquy on a theme previously aired by Larry Niven (in The Jigsaw Man), with a first-person semi-literate narrator. It’s just about perfect in its small compass and inexorable logic. Four miniature stars.

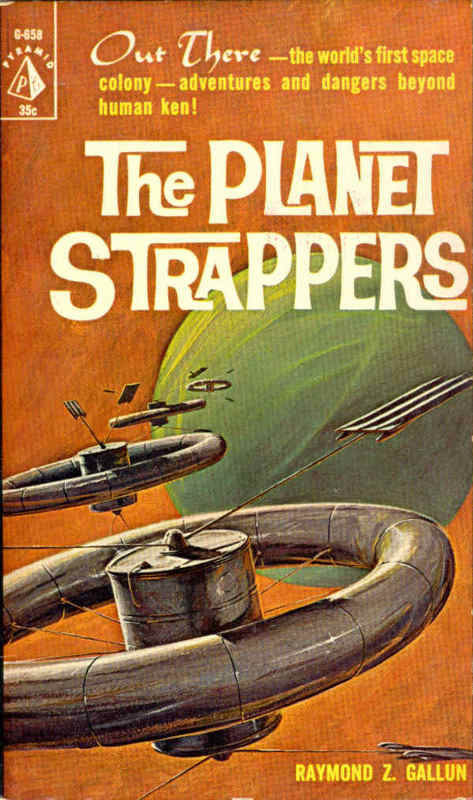

Sarker’s Joke Box, by Raymond Z. Gallun

The “Famous Classic” this month is Sarker’s Joke Box, by Raymond Z. Gallun, from the March 1942 Amazing. It’s yet another testament to the corrupting effects of Ray Palmer’s editorship. It begins: “Clay Sarker had me covered with his ugly heat-pistol. Kotah, the little Venusian scientist he’d held captive for so long, crouched helplessly chained, there, in one corner of Sarker’s cavernous mountain hideout. My life wasn’t worth the cinders in a discarded rocket-tube.” “Gimme bang-bang” wins out again! Pull out your copy of the June 1938 Astounding Science-Fiction, or the anthology Adventures in Time and Space, and compare Gallun’s much classier Seeds of the Dusk to this one.

by Robert Fuqua

But the story is not a total loss. The narrator is a cop, and he and his buddies have rousted Sarker out of his last stronghold in the Asteroid Belt. Now he’s trapped in a cave on Earth while the other cops are closing in. But Sarker—“that black-souled demon of space”—turns his heat-pistol on Kotah and then on his own apparatus that fills the cave, which blows up quite satisfactorily, then enters a metal cylinder and closes and seals it behind him. When the main body of cops arrive, they try to penetrate it, but—it’s neutronium! They can’t scratch it. And to compound matters, Sarker’s lawyer appears and announces that since they’ve declared Sarker to be in custody, they’ve got to try him within 60 days or he goes free. So the cops redouble their efforts to get through the neutronium. At this point, the story turns into a scientific puzzle without (much) further resort to hokey melodrama. It’s perfectly readable and commendably short. Three stars.

The Columbus Problem, by Greg Benford and David Book

Greg Benford’s second appearance in the issue is the first “Science in Science Fiction” article, done with David Book. It’s called The Columbus Problem and it starts out with a quotation from a Poul Anderson novel about a spaceship arriving at a new star system: “The instruments peered and murmured, and clicked forth a picture of the system. Eight worlds were detected.” Benford and Book then explain just how difficult and time-consuming it would actually be to detect the planets of an unfamiliar star system upon arrival at it, with our present technology or likely enhancements of it. They do a fine job of plain English explanation without becoming tedious. It beats hell out of Frank Tinsley’s earlier science articles for Amazing and edges Ben Bova’s. Four stars.

Summing Up

So, deferring judgment on the serial, here’s a lively issue of which much is quite good and nothing is a chore to read. Amazing!

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

![[October 8, 1969] Suddenly . . . (November 1969 <i>Amazing)</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/amz-1169-cover-672x372.png)

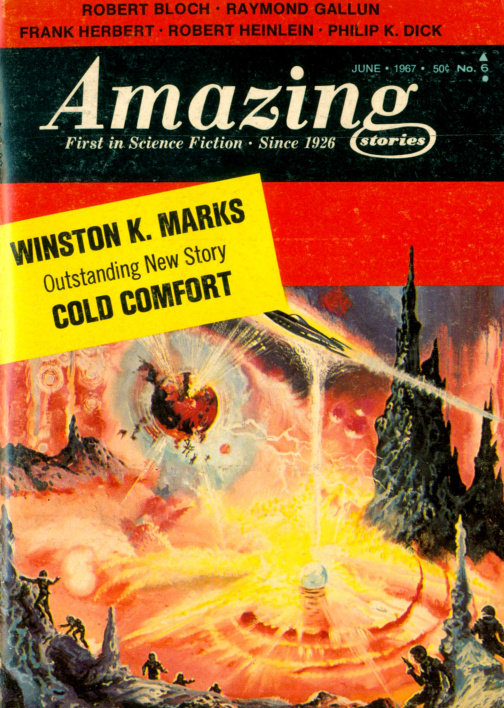

![[May 6, 1967] Stirred? Shaken? (June 1967 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/amz-0667-cover-504x372.png)