by John Boston

Last month’s issue raised high expectations, but this February Amazing reminds me of an infantile and scatological joke which I believe I heard in fifth grade, the punchline of which is “Coffee break’s over, squat down again.” If you never heard it, count your blessings.

Daniel F. Galouye’s novella Recovery Area comes highly touted. Last month’s Coming Next Month squib described it as “destined to become a classic” and “brilliantly original, and with a depth of meaning and emotion”; the story blurb says “There is no reason to write a blurb that will try to lure you into being interested in this story. It will grip you of itself within ten lines, and hold your mind and heart far beyond its last sentence.”

Actually, it’s a decent and well-meaning pulp novella, recalling the beginning of Galouye’s career in SF: 20 of his first 21 published stories appeared in Imagination, that most pulpish of digest magazines, in the space of two years. But it’s a step backward from the much more sophisticated Dark Universe.

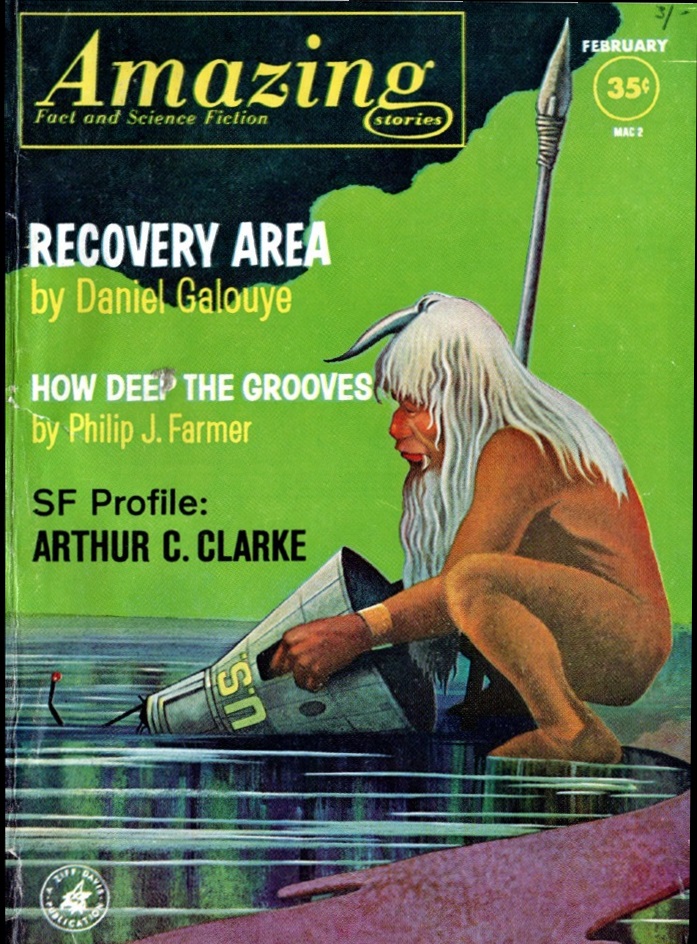

On Venus, it’s proposed, there is a species of giant humanoids (hideously illustrated on the cover by Vernon Kramer) featuring “quazehorns.” Say what? Horns that quaze, obviously—that is, they endow the bearer with a not-well-defined extrasensory power to perceive objects and entities at a distance, read personalities and attitudes if not quite thoughts, and perceive the nature of the contents of closed containers (i.e., the supply capsules for the Earth expedition that is about to land, which are dropped at various points near the landing site; hence the title.)

The Venutians (author’s spelling [others are using it, too. (Ed.)]) are materially primitive but highly philosophical, as attested by the extensive deployment of capital letters. In the first couple of pages, we encounter Meditative Withdrawal, Cognitive Posture, Ascetic Ascendancy, the First Phase of Ascendancy, the Dichotomy of Endlessnesses (comprising Upper and Lower), and the Eternal Day (where the Venutians live, squeezed in between the two Endlessnesses). These are the preoccupations of K’Tawa, the Old One, who is constantly beset by interruptions from the youngster Zu-Bach, always Materialistic. Right now Zu-Bach is concerned with Presences from the Upper Endlessness, who of course are the Earth explorers, and who Zu-Bach is convinced are malign after he sees one of their dropped capsules snatching an animal specimen which later turns up dead. Matters escalate when the explorers arrive and the Venutians quaze hate, scorn, treachery, and greed, mostly from one misfit member. Violent conflict ensues. Meanwhile, K’Tawa is achieving Phase Eight Meditation, putting him in touch with the memories of his ancestors, which murkily reveal a local cosmological history reminiscent of the theories of Immanuel Velikovsky, and suggest a startling provenance for the Venutians and a revised view of the universe. Understanding triumphs, facile happy ending follows. It’s competent and well-intentioned product, but we’ve come to expect better, from Galouye and everyone else, especially from something that is presented (and presents itself) as a major work. Three stars with a side of nostalgic indulgence.

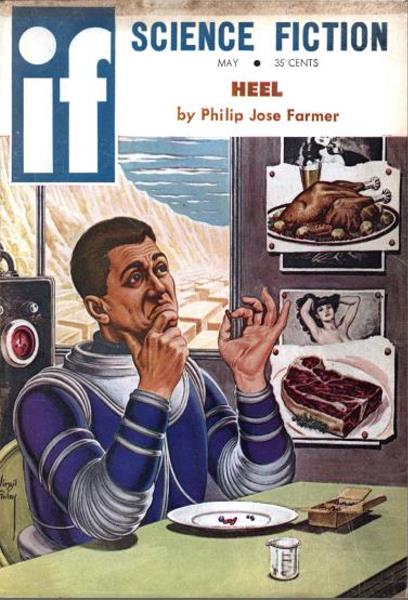

The biggest name here, also featured on the cover, is Philip Jose Farmer, with his short story How Deep the Grooves, which is pretty terrible. In a future police state, Dr. Carroad has, through the magic of electroencephalography, devised a machine that can turn thoughts into audible words, thereby unmasking deviationists. Now, with high officials watching, he’s going to use it to transmit, not receive, and indoctrinate his own unborn child to be unable to question the dictates of the state. Instead, the machine keeps receiving, and broadcasts the child’s thoughts at various future ages, demonstrating that we are all automatons programmed to play roles, and ending with an unsavory revelation about the futures of father and son. It’s reminiscent of an old silent movie filled with posturing and mugging, and all for the sake of an idea that would have seemed pretty silly even in the days of Hugo Gernsback. One star.

Speaking of Gernsback, he was six years gone from Amazing but his spirit was clearly still around when this month’s Classic Reprint was published (February 1935 issue). The Tale of the Atom, fortunately the only story by Philip Dennis Chamberlain, rings another silly change on the silly universe-as-atom theme, the silliness of which has been apparent since before this story was published. One star.

A higher class of silliness, maybe, is represented by Phoenix, a short story by Ted White and Marion Zimmer Bradley. Protagonist Max is standing swathed in flames, which it says here “feels like satin ice,” when his girlfriend walks in. Extinguishing himself, he says, “Hell of a time for you to show up, Fran,” noticing that the carpet is singed and smoking where he’s been standing on it. Oops! Max has had a sudden accession of psi powers, or something, including levitation and the ability to heat up his coffee by thinking about it and to dress himself psychokinetically, in addition to cloaking himself in flames and perceiving all of reality at the molecular level, or something like that. The story is his losing effort to maintain some human contact in the face of this transcendent experience, and his surrender to the latter. Something might have been made of this at greater length and with more writerly competence (Bradley’s been around but this is White’s first professionally published story), but in this form it’s alternately risible and merely inadequate. Two stars for ambition.

The remaining item of fiction is Jack Sharkey’s The Smart Ones, which is reminiscent of a Twilight Zone episode, both generally and specifically. (You’ll know the one.) Nuclear war is on the way, and ordinary people! just like you and me! are trying to figure out what to do. The story proceeds in a series of scenes that are both strongly visual and carried by dialogue—whether to go to the fallout shelter, whether to take the opportunity to get onto a Moon-bound ship—the best of which is the couple arguing about whether Vanity Fair and Coningsby should get space on the fallout shelter bookshelves. Later, after the bombing:

“ ‘I think the baby needs a change, or something,’ said Corey, looking down at his infant son.

“ ‘Read him Coningsby,’ said Lucille. Then she started laughing again, until Corey was forced to slap her face crimson to quiet her.”

You just know this guy wants to write for TV, or at least the stage, and he’d probably be pretty good at it. The more I look at this the better I like it in its black-humoresque way. Four stars, if only by comparison to its company.

Sam Moskowitz is back with another SF Profile, Arthur C. Clarke (guess he couldn’t think of a snappy title or subtitle), which bears the usual virtues and faults: interesting biographical material, sometimes dubious critical judgment, and a close focus on Clarke’s earliest work at the expense of the more recent. In Clarke’s case this is less jarring than in some of the other profiles, since Clarke didn’t start publishing SF professionally until 1946 and all but one of his novels are from the ‘50s and later, so Moskowitz has to discuss some recent work (he even mentions the 1961 A Fall of Moondust a couple of times, though he can’t get the title straight). Three stars.

So: a step forward, a step back. Lather, rinse, repeat.

[P.S. If you registered for WorldCon this year, please consider nominating Galactic Journey for the "Best Fanzine" Hugo. Check your mail for instructions…]