by Gideon Marcus

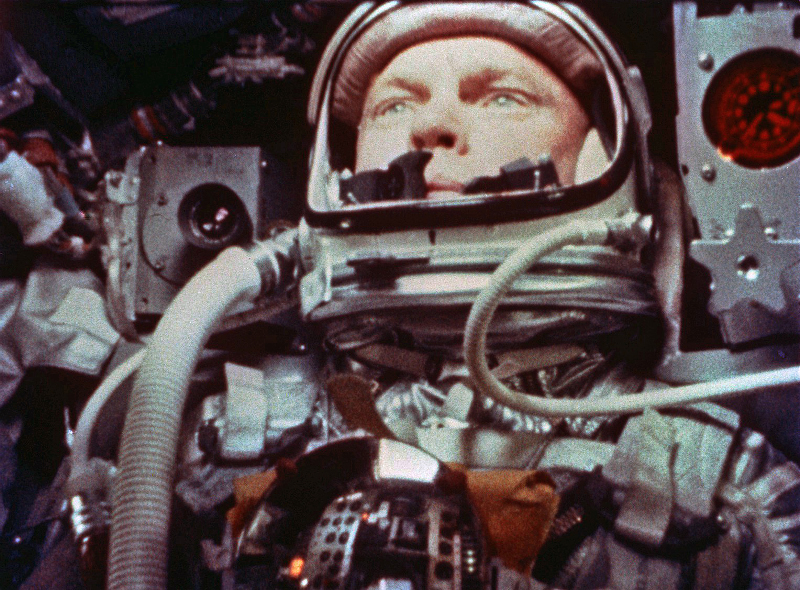

And the Free World exhales. At long last, an American has orbited the Earth. This morning, Astronaut John Glenn ascended to the heavens on the back of an Atlas nuclear missile. He circled the globe three times before splashing down in the Atlantic Ocean.

It is impossible to understate what this means for us. The Soviets have been ahead of us in the Space Race since it started in 1957: First satellite, first lunar probe, first space traveler. Last year, the best we could muster was a pair of 15 minute cannonball shots into the edges of space. For two months, Glenn has gone again and again into his little capsule and lain on his back only to emerge some time later, disappointed by technical failure or bad weather. Each time, the clock ticked; would the Soviets trump us with yet another spectacular display of technological prowess?

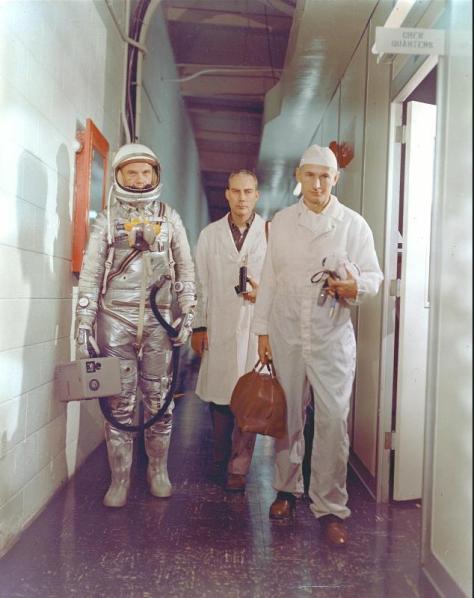

But this morning, everything was fine – the weather, the booster, the spacecraft, and the astronaut. As I went to sleep last night, Glenn woke up. He had the traditional low residue breakfast of orange juice, toast, eggs over-easy, fillet mignon, and Postum, before suiting up and entering the capsule. That was at 5 AM his time (2 AM mine). For five hours, the patient Colonel waited as his Atlas rocket, only recently tamed sufficiently for human use, was prepared and tested for flight.

At 9:47 AM his time, at last we saw the fire shoot out from beneath the missile, saw the Atlas and its black-painted cargo lift off, leaving its support gantry shrouded in white smoke. For several minutes, the flight of mission Mercury-Atlas #6 was a strictly aural affair, the TV cameras' only subject being the now-empty launchpad. But we heard the confident communication between Alan Shepard on the ground and Glenn hurtling skyward, America's first and American's latest spacemen, and we knew everything was still going well.

The sky went quickly from blue to black as Glenn struggled against six times his normal weight. First, the Atlas' two side engines exhausted their fuel and detached. A few minutes later, the central sustainer engine's job was complete, and the Mercury capsule, dubbed Friendship 7 by Glenn, flung itself from its empty booster. Glenn was now in orbit, weightless, and cleared for his full three-orbit, five-hour mission.

For the first time, an American flight was long enough for the public to contemplate, to be worthy of news flashes. And even though the last Soviet flight had spanned a full day, it was shrouded in secrecy until after its completion. Glenn's mission was, on the other hand, entirely open. Cockpit chatter was broadcast in the clear; each success and potential failure was presented for the world to hear. Space travel had become a spectator sport.

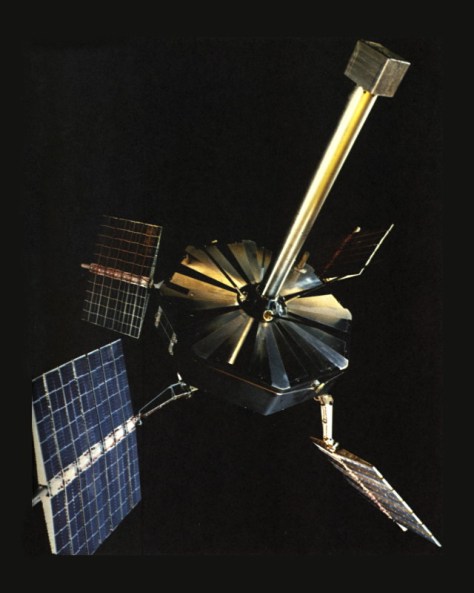

The world participated. Indeed, it had to. An orbital mission requires global tracking. Glenn's flight was monitored as he passed over exotic locales like Zanzibar, Woomera, Hawaii. The citizens of the west Australian city of Perth turned their lights on for the astronaut's passage, providing a virtual streetlamp as he whizzed overhead at 18,000 miles per hour.

Three sunsets and three sunrises greeted Colonel Glenn, though he was given precious little time to appreciate them, so crowded was his schedule with experiments and ship operations. As the Mercury spacecraft's functions began to degrade in its third orbit, the value of an experienced human pilot became evident. Glenn manually configured and trimmed the vessel to make the most of the journey and ensure the mission could be completed.

Glenn's biggest challenge came at the end of the mission. Sailing backwards over the Earth, the astronaut prepared to fire the ship's retrorockets, a blast of fire that would slow the craft such that it could break out of orbit and back toward ground. But an indicator suggested that the Mercury's heat shield was loose. If that were true, then there could be no returning for the astronaut – he would burn up on reentry.

Was there anything the astronaut could do about the situation? Well, the retrorocket package was held tight against the bottom of the bell-shaped craft (and thus, its heat shield) by a series of straps. Normally, the retrorockets would be discarded before reentry. This time, on the advisement of ground control, Glenn left the retrorockets strapped in. The hope was that the straps would keep the shield attached, if it was indeed loose.

What a terrifying display that must have been for the pilot, watching flaming chunks of the retrorockets fly past his window as he tore through the white-hot outer layers of the atmosphere. Glenn had plenty of other things to worry about. The "G" forces spiked as the craft decelerated, and the ionization of the air cut off radio contact. We all waited, white-knuckled, for some sign that the astronaut had survived the journey…or had been vaporized.

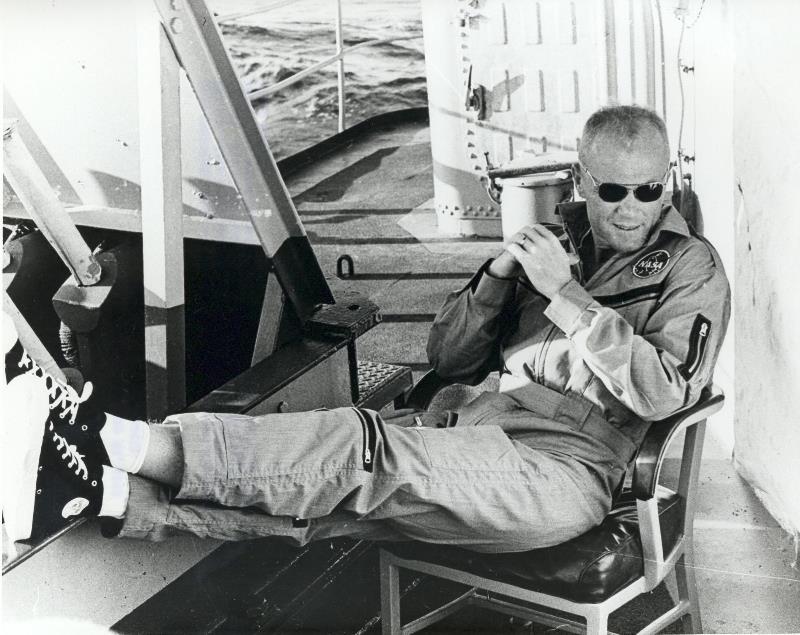

Then his voice crackled over the air again, the Mercury's striped parachutes were deployed, and we began breathing again. A ship of the recovery fleet, the little destroyer called the U.S.S. Noa, was already close at hand when Friendship 7 touched down in the waves. Once the capsule was hoisted aboard, the astronaut popped the side hatch, the one that had exploded prematurely for second astronaut Grissom. An overheated but grinning Glenn stepped out of the Mercury, and into history.

Mercury's primary mission, to orbit and safely return a human, has been completed. Nevertheless, there is obviously much life left in the bird. Three more three-orbit flights are planned to shake out the bugs that plagued the latter portion of Glenn's flight. Then 12, 24 hour, and perhaps multi-day flights are slated.

Of course, the Soviets may soon respond with a flight that trumps ours, perhaps even a two-person mission. But for now, the hour rightfully belongs to the West. The democracies of the world at last have their emissary to the stars.

Godspeed, John Glenn!