by Margarita Mospanova

In every reader’s life there comes a time which we all dread. A time we try to forget as soon as it happens. A time when we finish reading a book that by all accounts should be a delight but that instead bores us to tears and makes us wish time travel was real just so we could go back in time and skip the experience altogether.

And sadly, dear readers, that is exactly what happened to me when I turned the last page of The Amphibian.

But first things first.

The novel was written by Alexander Beliaev in 1927 and published just a year later, first in a magazine, and then as a stand-alone book. It was published in English in 1962 by Moscow’s Foreign Languages Publishing House.

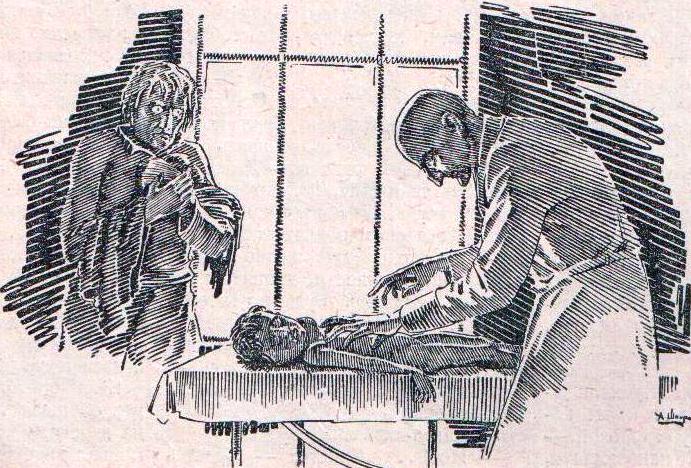

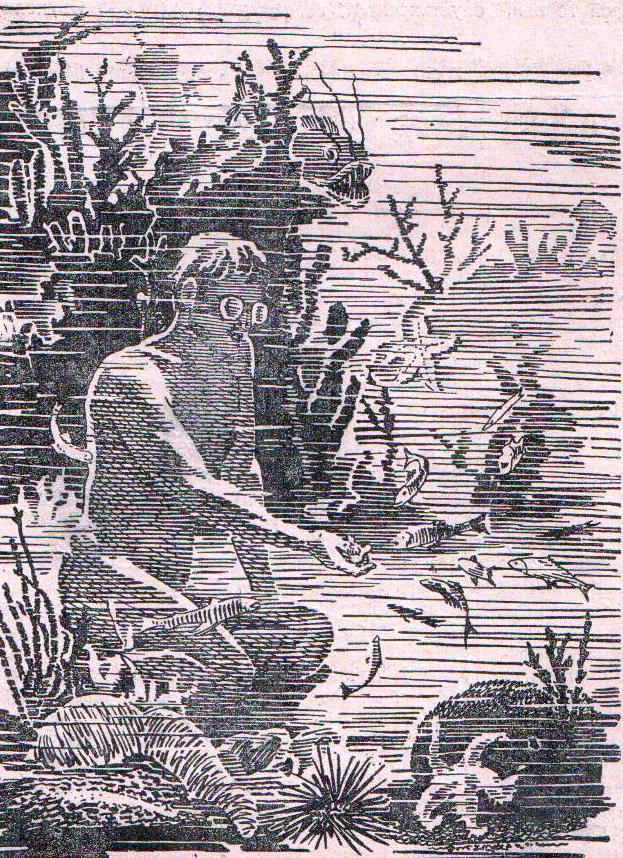

The story is set in Argentina and follows Ichthyander, an adopted son of a world-renowned surgeon, Salvator. When he was but an infant, Ichthyander was very ill and to save his life Salvator transplanted a set of shark gills onto him, giving his son the ability to breathe underwater. Hence the name, as the parts of it come from Ancient Greek, translating to “fish” and “man”. The pair live a fairly idyllic life in large mansion, the father treating locals and the son spending much of his time playing in the ocean.

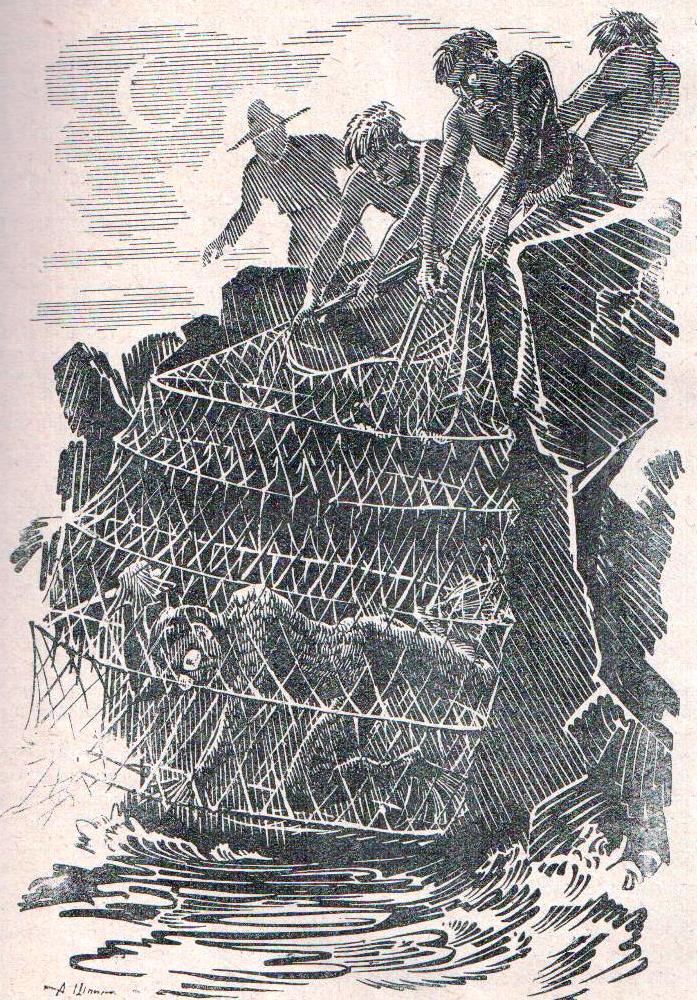

However, as Ichthyander grows older, he become more reckless, attacking Argentinian fishermen and returning their hauls back to the water. Until one day, one of the local pearl gatherers, Pedro Zurita, sees him, and realizing the boy’s potential as a pearl diver, tries to catch him.

That doesn’t sound too bad, you might say. And you would be right, the plot looks quite interesting. In theory. In practice, the story has been flung head first against a truly horrendous writing style, flat characters, and unnatural dialogues.

The Russian text reads like a badly done translation. It is all the more unfortunate, when the rest of Beliaev’s books (at least the ones I’m familiar with) are written perfectly well. I suppose the author wanted to mimic the often more abrupt style favored by Western writers, but if so, he failed. And failed spectacularly.

Therefore, it will not come as a surprise when I say: read the book in English. Ignore the original Russian text and skip right to the translated version. I dare say, you will find yourselves much more satisfied with the book than I did.

Still, there were a couple of passages, all of them describing nature, the ocean specifically, that hinted at what the book might have been had the prose been more… engaging. But they were few and far between.

Out of all the characters the only ones that had at least a small spark of life in them were Baltasar, Zurita’s right hand and the father of Ichthyander’s love interest (don’t start me on that particular train wreck), and Zurita’s mother, a cranky old woman. The rest were blander than cardboard.

(You might have noticed – I really didn’t like the book.)

And now we come to the crux of the problem. The book was bad. Why would I, or anyone else for that matter, bother to read it?

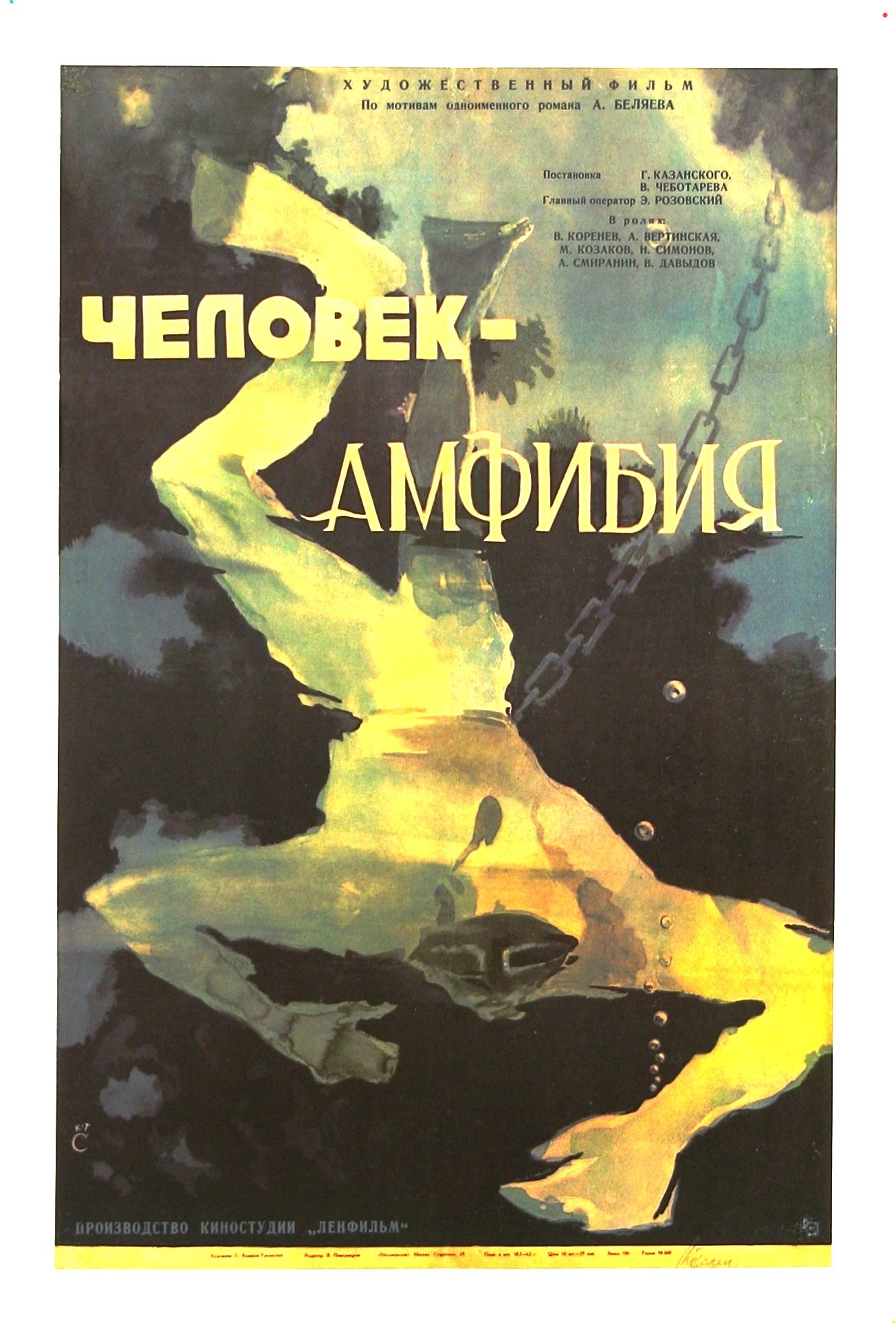

And the answer, dear readers, is that in 1962 it was made into one of the best movies I’ve ever seen in my life.

The Amphibian Man turned flat and uninteresting characters into real people, dry prose into stunning visuals. It has you gripping the edges of your seat, from the beginning to the very end. You fret over Ichthyander’s naive and innocent nature, tie yourself into conflicted knots over don Pedro’s actions, empathize with Salvator, and curse the cruel Argentinian policemen.

This is a movie that, I’m sure, we will be watching even after the turn of the second millennium, no matter how optimistic that sounds.

And The Amphibian is the book that made it possible. That alone turns it into a worthy read, even if nothing else does. That is why, at the end of it, I give The Amphibian one bookish and five cinematic stars out of five.

(Now go watch the movie!)

[And come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

![[Apr. 4, 1964] A taste of brine (the book and movie, <i>The Amphibian</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/640403AM_1-672x372.jpg)

![[August 23, 1963] Laughing Mushrooms (Ishirō Honda's <i>Matango</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/630823matango-300x372.jpg)