There are days when everything goes right.

Here we are at the end of a difficult year for space travel. The Air Force had nearly a dozen failures in a row with its Discoverer proto spy satellite. The Pioneer Atlas Ables moon shots were all a bust. Even the successful probes rarely made it into space on the first try, viz. the communications satellites, Echo and Courier. The American manned space program was dealt a number of setbacks, limping along at a pace that will likely get it to the orbital finish line quite a bit behind the Soviets.

But Discoverer now has enjoyed a several-mission success streak. The latest Explorer probe is sending back excellent data on the ionosphere, and its elder sibling is still plugging away in orbit, returning information on the heat budget of the atmosphere. TIROS 2 provides up-to-date weather photos from overhead.

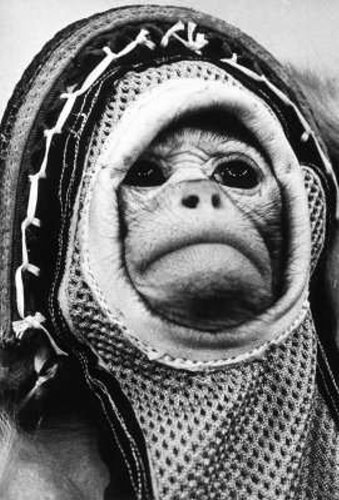

And this morning, just a few hours ago, Mercury Redstone 1A carried a production model Mercury spacecraft into outer space. The suborbital mission took only 15 minutes, but it was an exact duplicate of the trip a human astronaut will take in the next few months. The capsule was retrieved from the Atlantic in short order, and to all accounts, the flight was a complete success. Just one more mission, crewed by a trained chimpanzee, and after that, America will have a man in space.

It is still unknown just who that person will be. Any of the "Mercury Seven" are qualified, of course. Moreover, the group includes representatives all three branches of service that fly jet planes (Air Force, Navy, and Marines) so I don't think that will be a factor. John Glenn is the most charismatic; Alan Shepard has the most test pilot hours; Scott Carpenter is the handsomest; Donald K. (Deke) Slayton has the most appealing nickname.

It's probably a good thing I'm not in charge of the selection process!

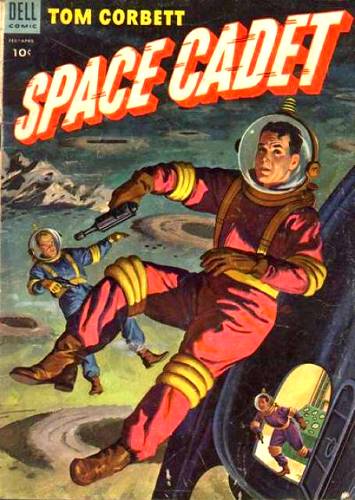

Speaking of good days, I am currently holed up in The Book Tree, a lovely little book store on Adams in San Diego. The proprietor is kindly allowing me to bang on the keys of my portable typewriter so I can get this stop-press out. He has an excellent science fiction selection, including an intriguing new book I picked up by Ben Barzmann: Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star, which I hadn't seen on the shelves of my normal haunts. I highly recommend this establishment!

And now, back up Highway 395, the fast way to Escondido from San Diego. See you soon with a review of this month's Analog…