by Gwyn Conaway

“Flowers are better than bullets.”

This has been said upon occasion, especially over the last decade, but in bygone eras as well. War-weary Americans and English poets alike have waxed poetic over the familiar adage. These days, however, the sentiment is laced with gunpowder.

Jan Rose Kasmir put flowers in guns pointed at her during a protest at the Pentagon in 1967 at which she wore a cotton shift decorated in daisies. She recalls being saddened by how young the soldiers were. These were men she could have been on a date with, if only there weren't a philosophical trench separating them.

Allison Krause also said this as she put a flower in an Ohio National Guardsman's gun at Kent State University on the weekend of May 4th, 1970, less than two months ago. Later, the Ohio National Guard opened fire on student protestors, wounding nine and killing four, including Miss Krause. Since then, students nationwide have protested in the name of peace and a growing distrust of the government's motivations to use deadly force, both at home and around the world.

Of course, the photograph of Mary Ann Vecchio, just 14 years old, will live in infamy for generations. The chilling scene still haunts me, the young girl wailing over the body of a fallen boy with shaggy hair and a pair of flat-soled sneakers.

Mary Ann Vecchio, 14, cries over the body of Jeffrey Miller, one of the four victims during the Kent State Massacre on May 4, 1970.

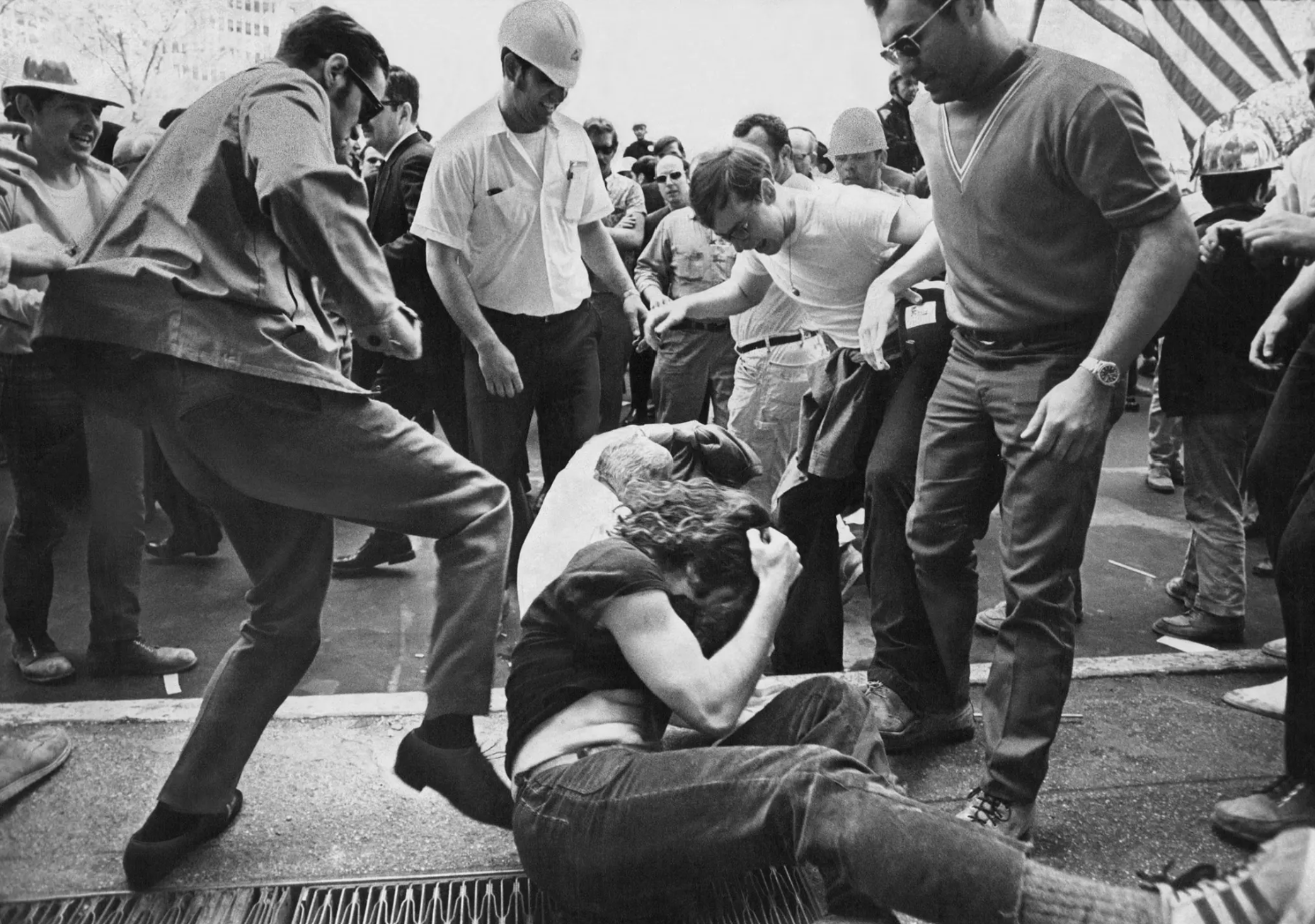

And just four days later, during a New York City protest honoring that boy in his sneakers and the other students that died, a band of several hundred laborers and office workers also took to the streets. The Hard Hat Riot was a culture clash that illustrates the divide in America.

Long hair versus trim cuts. Band shirts versus button-downs. Bell bottoms versus slacks. This division is more than a generational or political gap. Our country is splitting down the seams of ideology. The Hippies had been a countercultural movement in the sixties, but I am certain that events like these will transform their radical ideals and fashions into the mainstream.

Though people on opposite sides of the picket line see dramatically different messages when they judge the fashion identities of these men, the message couldn't be clearer. The rift in America will have a lasting impact.

Since the Vietnam War protests began in 1965, “Flower Power” has been a consistent message for the movement, expressed in wacky, beautiful, creative, and bold ways. Daisies, a flower ubiquitous across the nation in gardens and the wild, is the flower of choice with its pure white petals and plush center. The term signals a commitment to pacifism and peaceful protest but is transforming before our eyes.

A British man wearing a provocative flowerpot hat decorated in silk flowers with a pair of spectacles, one of which is patterned as a daisy. He likely wore this to a festival in 1967.

Continue reading [June 26, 1970] Hard Hats & Flower Power Collide

![[June 26, 1970] Hard Hats & Flower Power Collide](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Screenshot-2025-06-18-230824-672x372.png)