[if you’re new to the Journey, read this to see what we’re all about!]

by Gideon Marcus

Remember five years ago, when Explorer 1 was launched? At first, the big news was that America had answered Sputnik and joined the Space Age, but it soon became clear that the flight had larger significance. For Explorer discovered the giant bands of hellish radiation that girdled the Earth, particles trapped by the Earth's magnetic field. Until 1957, these "Van Allen Belts" had been virtually unsuspected. With one flight, our conception of the universe had drastically changed.

It's happened again.

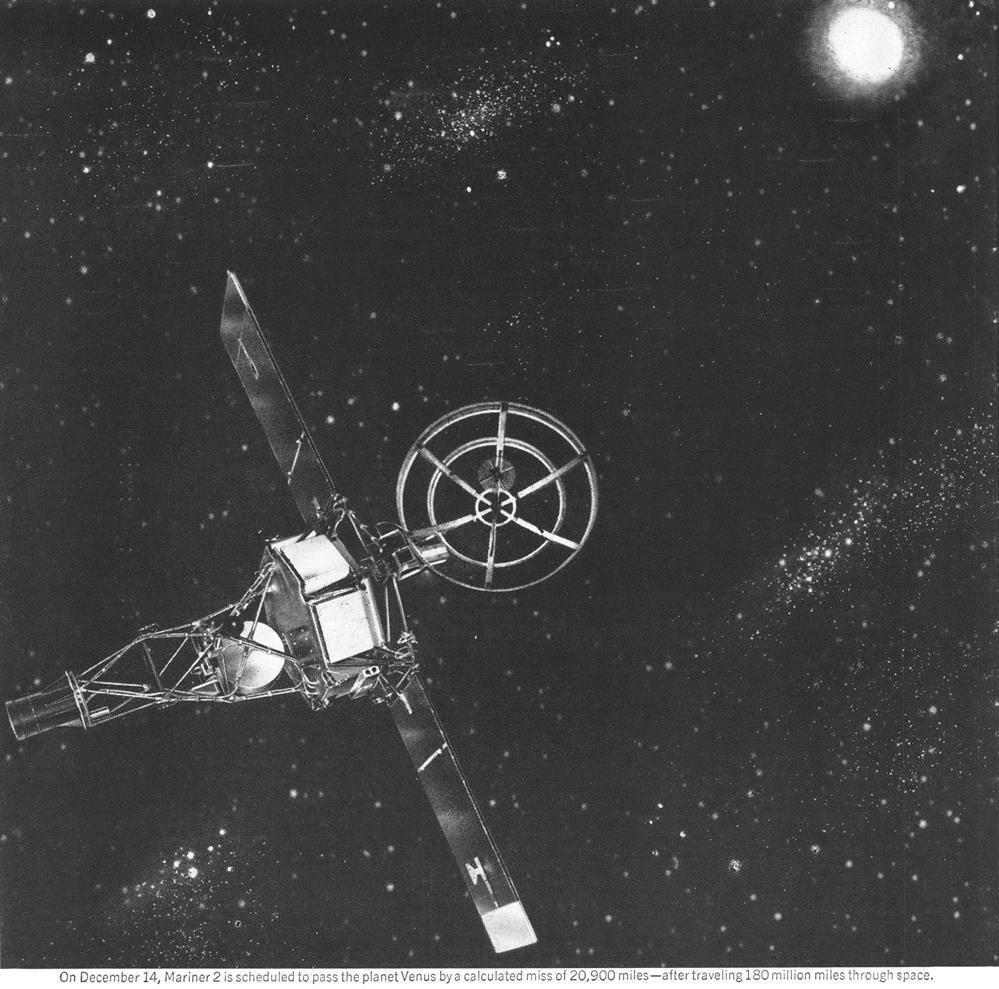

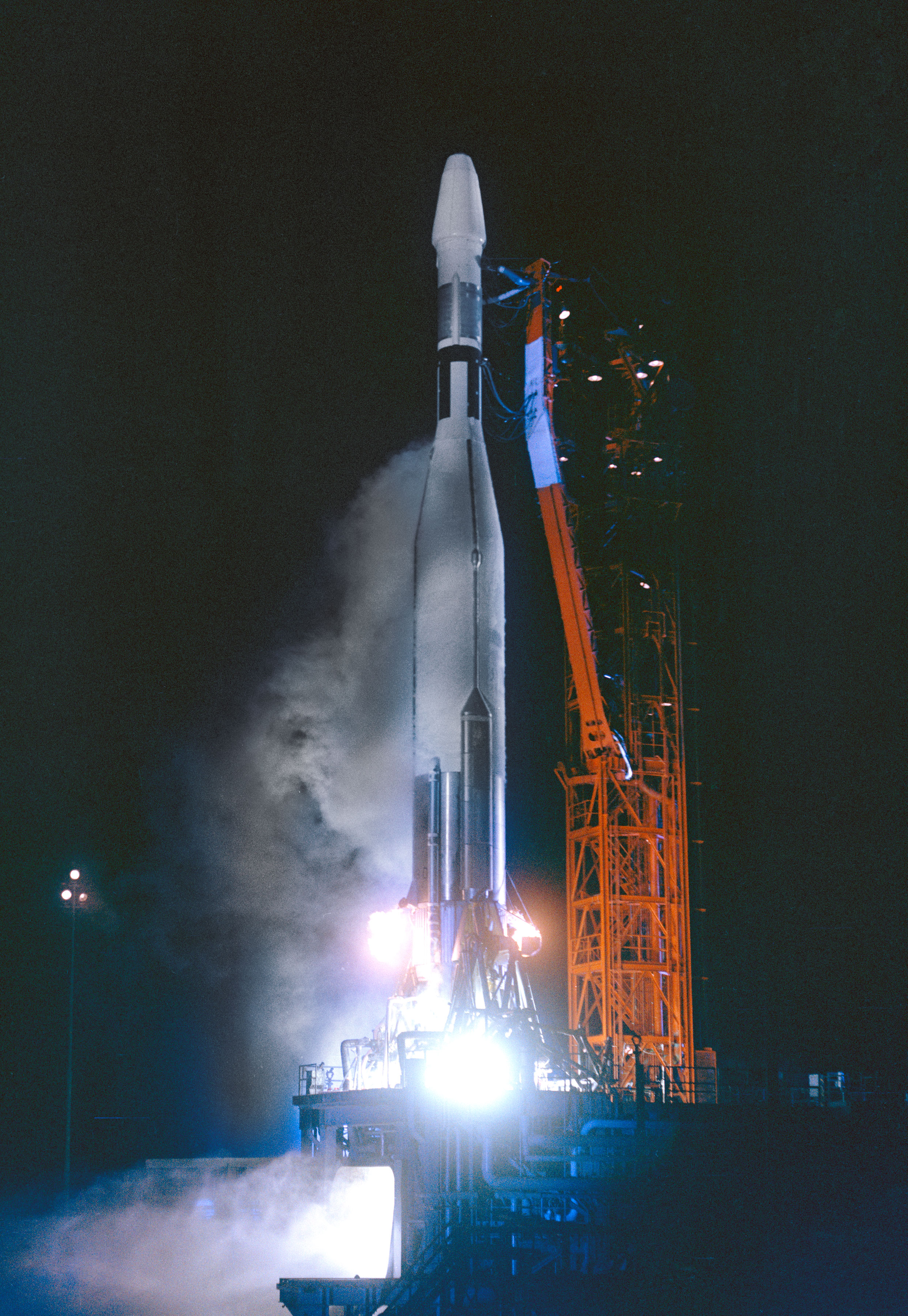

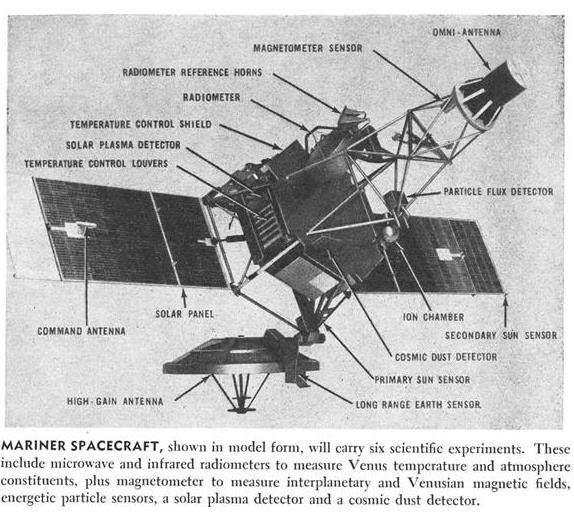

Mariner 2 is humanity's first successful mission to another planet, and the scientific harvest is absolutely enormous. Moreover, thanks to recent changes in policy, the initial results of this harvest were released unprecedentedly quickly (scientists are now reporting upon submission and acceptance of papers rather than publication). Just one month since the probe's encounter with Venus, the flood of information has been almost too much to parse; nevertheless, I think I've gotten the broad strokes:

Getting there is half the fun

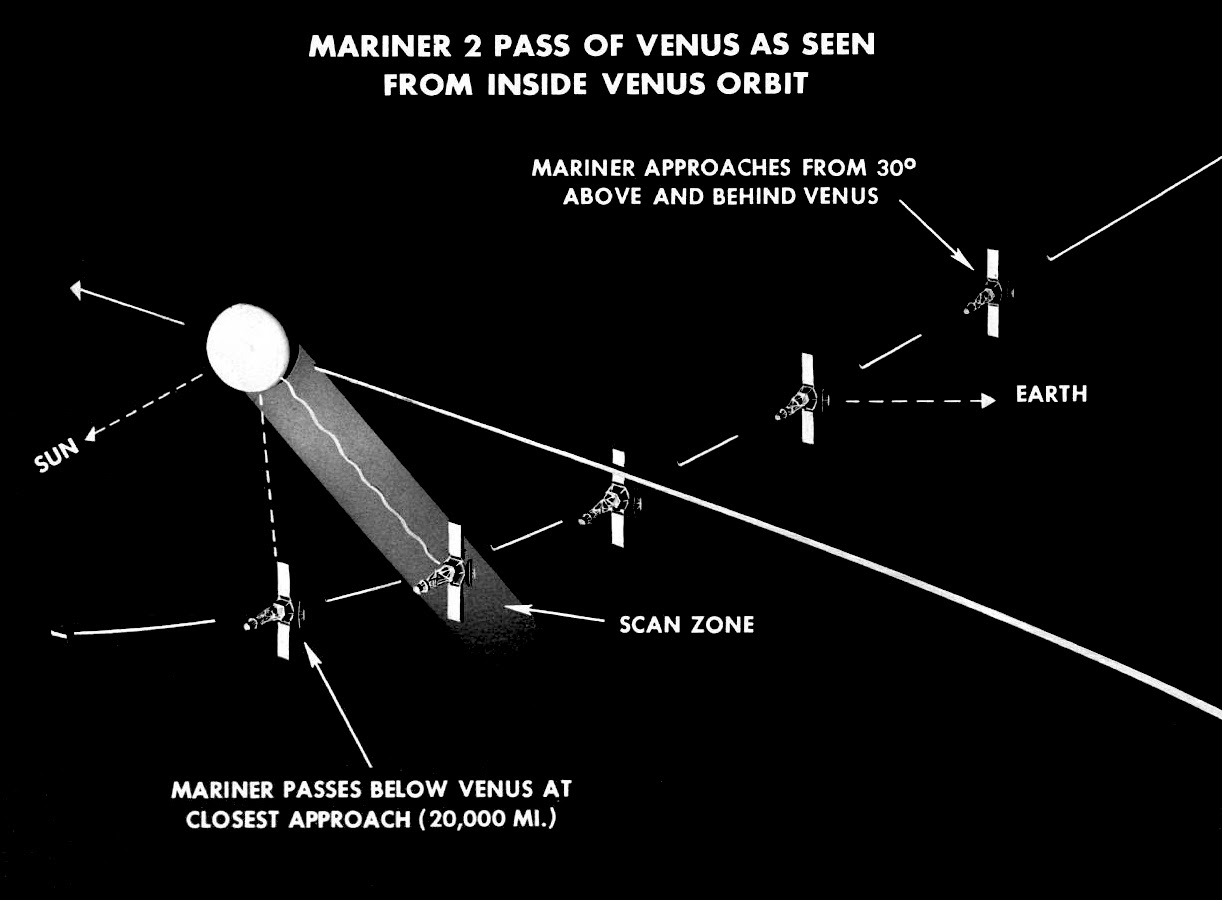

Before I talk about Mariner's encounter with Venus, it's important to discuss what the spacecraft discovered on the way there. After all, it was a 185 million mile trip, most of it in interplanetary space charted but once before by Pioneer 5. And boy, did Mariner learn a lot!

For instance, it has finally been confirmed that the sun does blow a steady stream of charged particles in a gale known as the "Solar Wind." The particles get trapped in Earth's magnetic field and cause, among other things, our beautiful aurorae.

Mariner also measured the interplanetary magnetic field, which is really the sun's magnetic field. It varies with the 27-day solar rotation, and if we had more data, I suspect the overall map of the field would look like a spiral.

Why is all this important? Well, aside from giving us an idea of the kind of "space weather" future probes and astronauts will have to deal with, these observations of the sun's effect on space give us a window as to what's going on inside the sun to generate these effects.

One last bit: along the way, Mariner measured the density of "cosmic dust," little physical particles in space. It appears that there's a lot of it around the Earth, perhaps trapped by our magnetic field, and not a lot in space. It may be that the solar wind sweeps the realm between the planets clean.

Unattractive planet

Given how magnetically busy the Earth is, and since Jupiter fairly crackles on the radio band thanks to its (likely) magnetic dynamo, one would expect Venus to impact its local space environment. Nope. In fact, Mariner 2 flew past the second planet without detecting a trace of Venusian magnetic field, nor any concentration of space dust around the planet. Now, it's possible that Venus has a weak field, or that its field is so oddly shaped that Mariner just hit a low patch, but the simplest explanation is usually the right one — Venus has no magnetic field.

Taking her temperature

Right up until December 14, some scientists (and many writers!) had held out hope that the thick clouds of Venus hid a reasonably hospitable surface, potentially teeming with life. Earth-based sensors had indicated that the Venus was unbearably hot, but such could be explained by an unusually active Venusian ionosophere. But as Mariner 2 turned its microwave and infrared radiometers across the face of Venus, it was clear that the edges of the planet were cooler than the center. This is what one would expect from a hot surface, cooler atmosphere; the reverse would be expected of the "hot ionosphere" model.

So how hot is Venus? At least 400 degrees Kelvin (260 degrees Fahrenheit), and probably a lot more. There's no way there is any liquid water under that hellish greenhouse of carbon dioxide. Moreover, it's not any nicer at night time. There appears to be no real difference in temperature between the illuminated and dark halves of Venus, probably for the same reason the Earth's oceans run a fairly consistent temperature – Venus' atmosphere is thick enough for efficient distribution of warmth.

Amtor dispelled

Mariner 2 and terrestrial radar have determined that the Venusian day incredibly long (~250 days, backward with respect to the other planets), but the Venusian winds blow across the planet far faster than the planet rotates; clouds have been seen racing around the disk of Venus in just 4-5 days. Recent radar observations indicate that Venus's surface is smoother than that of the Earth or the Moon.

This, then, is our new picture of Venus. It is a truly hellish place, more worthy of its less common moniker, Luciferos — a bleak, half-lit world scoured by hurricane-strength sandstorms hot enough to melt lead. Bradbury's All Summer in a Day, not to mention Burroughs' "Venus" series', will need some serious revision.

Details, details

One of the nice things about sending a probe far from Earth is it allows for more accurate measurement of basic units – like the distance of the Earth and Venus from the sun. This will help in future expeditions, manned and unmanned. Another bit of bounty from Mariner's flight is a refinement of the mass of Venus. It is 81.485% that of Earth – one of the few ways Venus remains "Earth's Twin."

What's next?

Opportunities to explore Venus occur every 19 months, when the second and third planets of the solar system are aligned in their orbits for easy travel. Mariner 2 was so successful in its mission that NASA has canceled plans for a repeat flight in 1964. Rather, the space agency will focus on Mars that year and follow up with Venus later, perhaps 1965.

One reason to launch a new probe to Venus sooner rather than later is, despite the wealth of information passed back by Mariner 2, we did not get a single photograph of the planet. That's because the spacecraft was too small to carry the transmitting equipment required to send back pictures from so far away. But by '65, the new Centaur booster stage will have replaced the weaker Agena, which will allow a beefier payload.

In the meantime, telemetry is worth a thousand pictures. For now, let us revel in this scientific bonanza. Venus may not be a great place to live, but visiting has paid off tremendously.

(that's rolls of data, not paper towels)

[P.S. If you registered for WorldCon this year, please consider nominating Galactic Journey for the "Best Fanzine" Hugo. Check your mail for instructions…]