by Gideon Marcus

Wall to Wall Coverage

When President John F. Kennedy, on May 4, 1961, commited the United States to "achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth," he initiated not one, but several parallel endeavors.

To land a man on the Moon requires not just a spaceship, a rocket, and the infrastructure to support them, it requires reconnaissance. When the President made that speech, the closest photographs of the lunar surface had been taken from 250,000 miles away. The smallest details our 'scopes could make out at the time were about a quarter mile wide. This is fundamentally useless when trying to determine whether a given site is flat enough to be suitable for landing a spacecraft. Guessing the height of lunar mountains from their shadows at such resolution was similarly impossible. Who knew how many hidden peaks lurked to snag Apollo astronauts on their way down?

Project Ranger was NASA's first major lunar project, each spacecraft taking pictures of the Moon before crashing into it. Three successful missions achieved resolutions as sharp as a foot and a half. Good enough, resolution-wise, but can you imagine having to send a Ranger for any one of dozens of potential landing sites? The cost would be prohibitive. Ranger's follow-up, the soft-landing Surveyor was able to determine if the lunar surface could be landed on, but it was no better at mapping the Moon than Ranger.

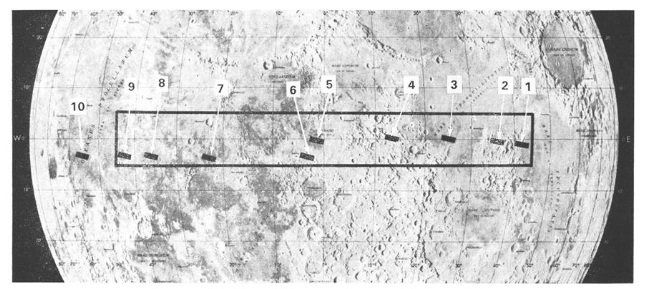

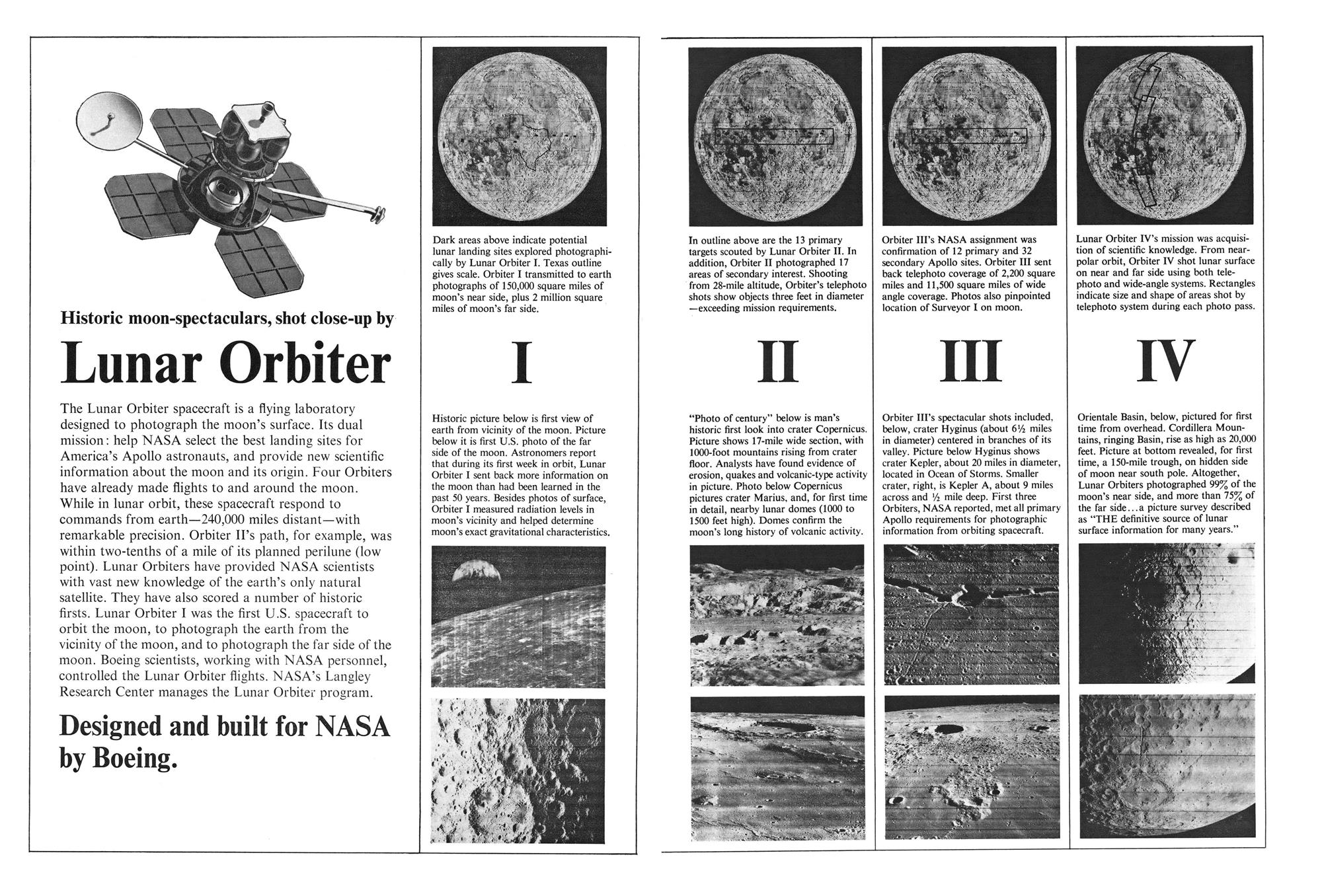

Potential Apollo site areas

As early as 1960, NASA knew it would need an orbiting spacecraft if it was ever to thoroughly map the Moon. There was Earthly precedent — the Discoverer spy satellite was at that time already taking high resolution photographs of the Earth for military surveillance purposes. But getting a spacecraft all the way to the Moon, and it being able to provide footage of 99% of the lunar surface? That was another kettle of fish. That required a big rocket to carry a big satellite that could carry a big imaging system. TV imaging was quickly discarded as being too bulky and low resolution.

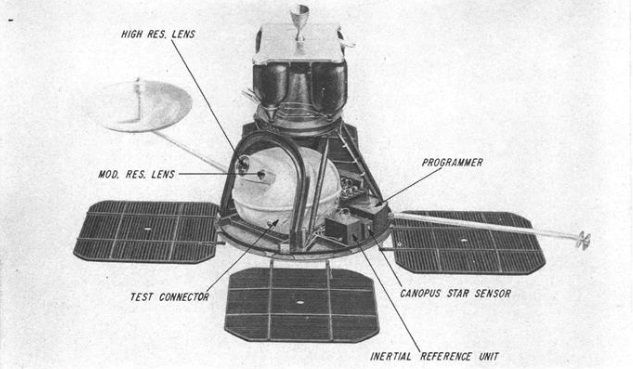

In 1962, Space Technology Laboratories put forth an orbiter proposal that used a film system, with each frame to be imaged and transmitted back to Earth. This was the first workable design, and combined with elements of an RCA proposal, NASA was able to officially solicit contractors for the project in mid-1963. Ultimately, Boeing won the contract, in large part because of their design's use of Eastman Kodak's new dry film development system. Their camera would be more reliable, lighter, and less susceptible to solar flares ruining the photos.

Like Scales Falling from the Eyes

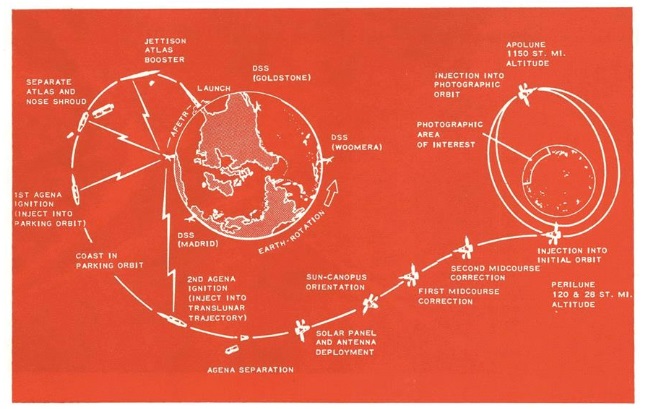

It took more than two years of development, but by 1966, the 850 pound Lunar Orbiter was ready. Using the same Atlas Agena as Ranger, the first spacecraft roared off to the Moon on August 10. Despite some navigational failures and a bit of overheating, Lunar Orbiter 1 braked into lunar orbit on August 14. The next day, the spacecraft began sending back pictures–not of the Moon, but of previously developed images, to test the system.

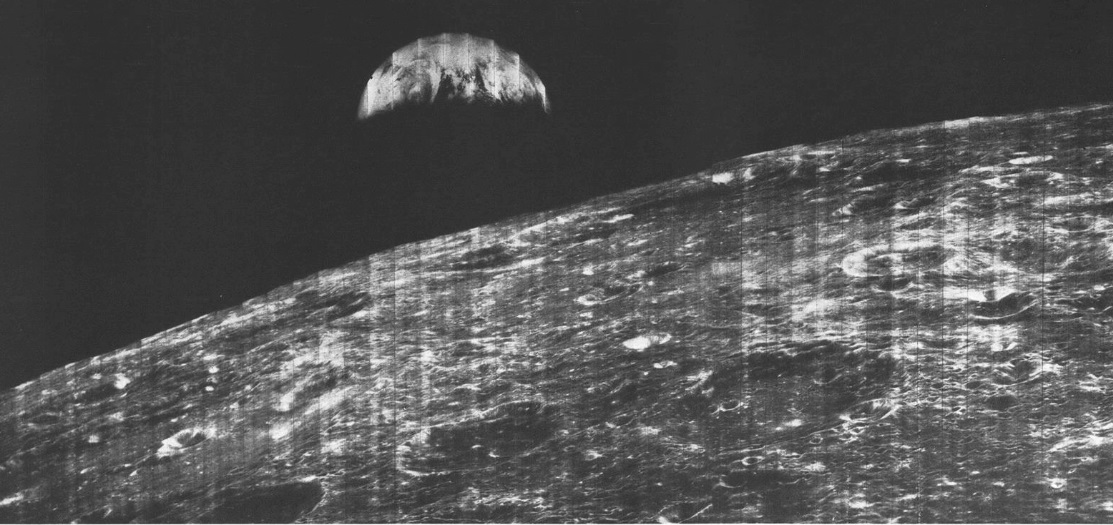

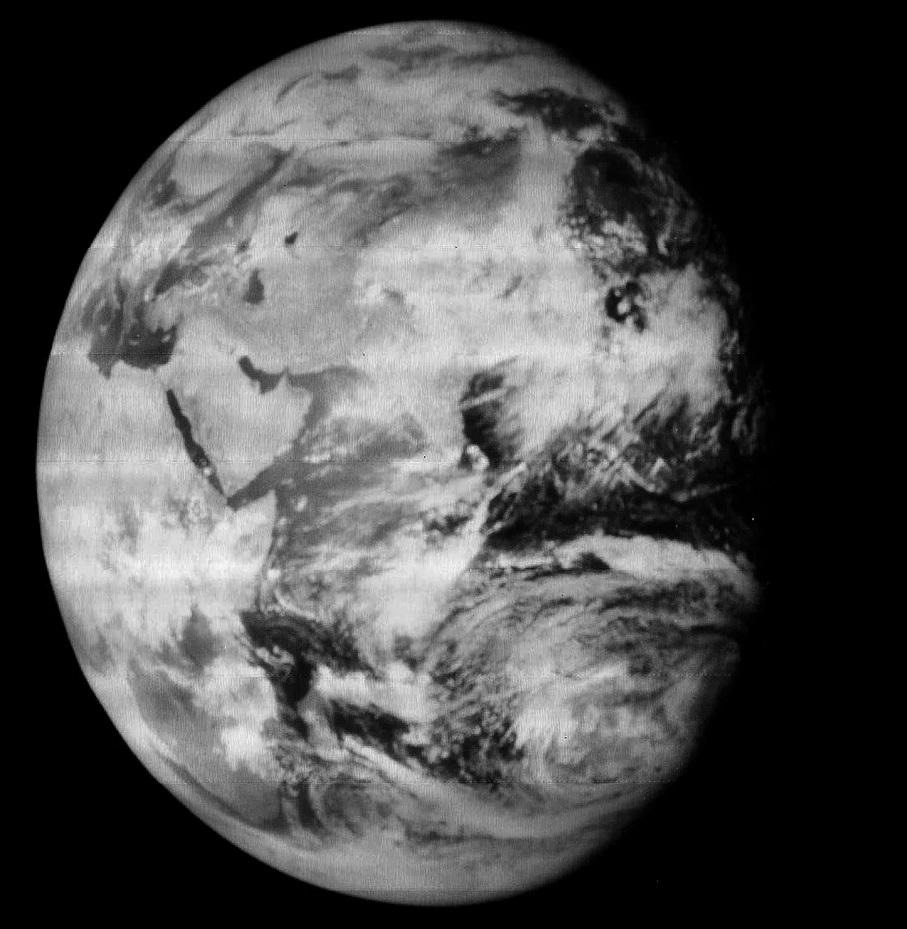

Issues plagued the high-resolution camera system throughout the mission, smearing many of the photos. But by August 29, Lunar Orbiter 1 was able to take 205 pictures of the Moon at altitudes ranging from 1000 to just 30 miles (no air means an orbit can be as low as you like), readout of which began August 30 and finished September 16. All of the major Apollo landing sites were photographed, and at high contrast. The cherry on top of the lunar sundae was this photograph of the Earth, the first taken from the vicinity of the Moon, and the longest distance snapshot of our home planet:

This did not mark the end of the first Lunar Orbiter's mission. For the next six weeks, NASA continued to receive telemetry and data from the probe's micrometeor detectors (no hits recorded). But by October 28, Lunar Orbiter was a sick ship, indeed, running low on stabilizing jet fuel, overheating, and losing power. It was starting to broadcast erratically, which threatened to interfere with communications with the upcoming Lunar Orbiter 2. So, on October 29, during its 577th orbit, Lunar Orbiter 1 was directed to impact with the Far Side of the Moon.

Two for Two

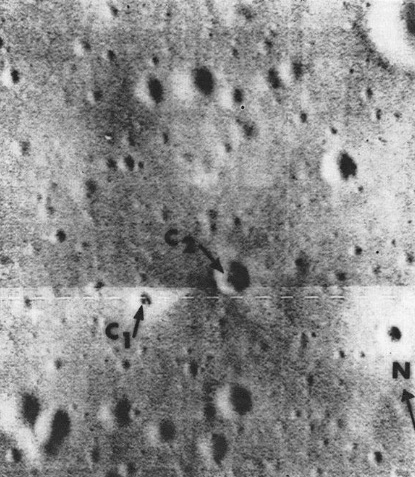

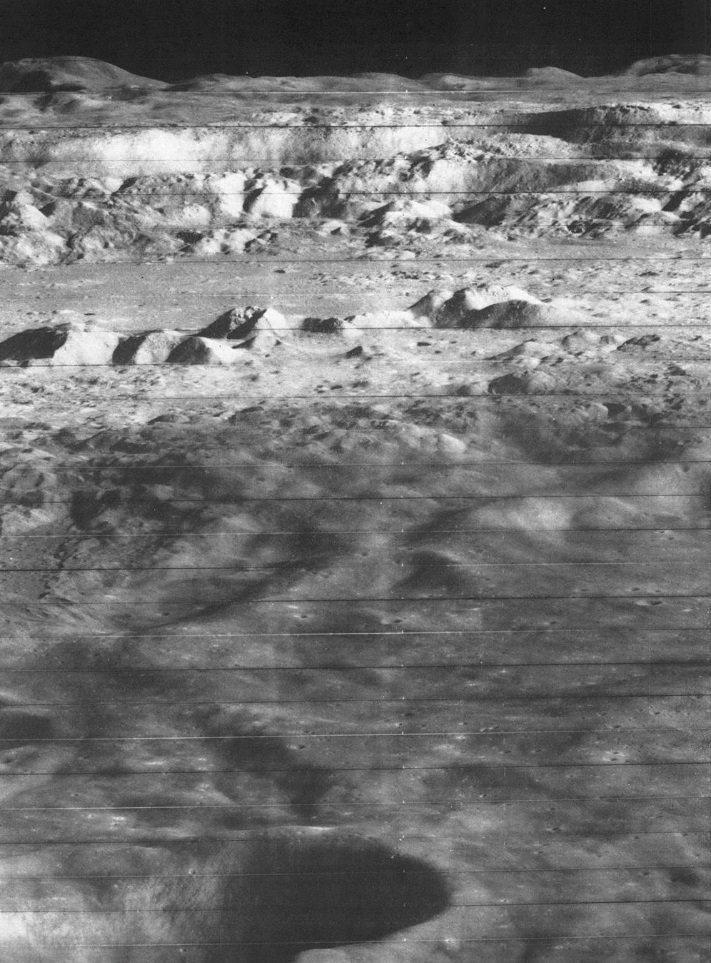

Just eight days later, on November 6, Lunar Orbiter 2 headed for the Moon. Much of it had been painted black, which addressed the navigation issues (glare blotting out the guide star Canopus). Overheating was avoided by frequent maneuvers to minimize exposure of heat-absorbing surfaces to the sun. By November 18, the spacecraft was snapping perfect medium resolution (for broad range) and high res (for potential landing site) pictures of the Moon from a 30 mile orbit. Mapping was done by the 26th and readout by December 7. Among the most significant shots included one of the Ranger 8 impact site and another dramatic photograph of Copernicus crater:

(C1 is Ranger's impact crater)

Copernicus from the side

817 pictures were taken in all, only six of which were lost due a glitch in an amplifier on the final day of readout. Lunar Orbiter 2 is still in orbit, returning data. In fact, it was hit three times by micrometeors back in November, probably by the same cometary fragments that give us our annual Leonids meteor display.

Following Up

Lunar Orbiter 3, launched February 7, 1967, had a more refined mission than its predecessors. Its job was to focus on promising sites its sisters had found rather than mapping willy nilly. NASA engineers planned to closely study its orbit around the Moon for gravitational wiggles, thus making a map of the Moon's insides as well as its surface.

Unfortunately, while the spacecraft was shooting pictures, the film advance mechanism started to balk. NASA terminated photography on February 23 after just 211 pictures. On March 4, with 72 photos still left to be transmitted back to Earth, the film advance motor burned out. Still, had NASA not stopped shooting pictures earlier, it is likely they would have lost all of the photos.

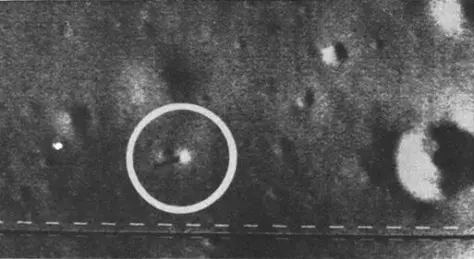

The shots they did get were unprecedentedly good, including this shot of the Surveyor 1 landing site:

Gilding the lily

At this point, the Lunar Orbiter program had already fulfilled its main requirement: documenting all possible Apollo landing sites. Now it was time to push the system to its limits. Lunar Orbiter 4 went up on May 4, 1967, beginning photography on the 11th. The spacecraft immediately ran into trouble. The thermal door that regulated camera temperature wasn't closing properly, letting light leak through. This led to a scramble to test the problem on the ground. Engineers were able to keep the door partially open, threading the needle between too much glare and dropping the temperature such that condensation fogged the film. The readout encoder started going, too. NASA cut off photography atfter 163 shots, but because the encoder was bleating erroneous signals, engineers had to work out a tedious, manual system for film advance and readout. Still, they got it done by June 1, resulting in 99% coverage of the Moon's near side at ten times the resolution possible from Earth. This revealed a bonanza of selenological detail. Plus, 80% of the Moon's Far Side had now been mapped, too.

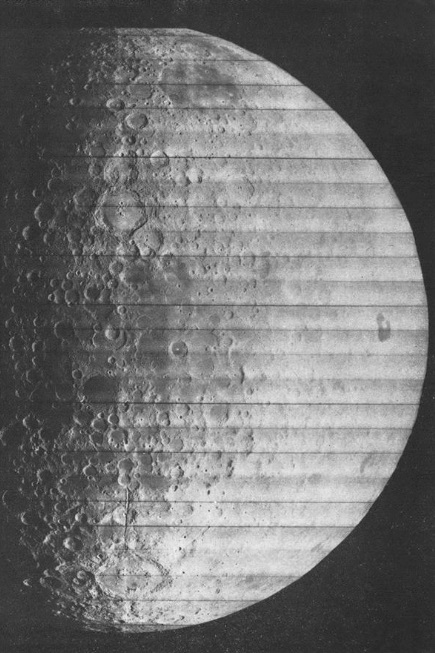

The last Lunar Orbiter went up on August 1 with a primarily scientific mission. Shooting began August 6, and on August 8, the spacecraft took an historic shot of the full Earth:

All of the planned 212 shots were taken by August 18 covering five Apollo sites, 36 science sites, and 23 previously unphotographed sites on the lunar Far Side. An unqualified success, the spacecraft will enter the next phase of its life this week, returning data on the lunar environment and gravitational field along with the still orbiting Lunar Orbiters 2 and 3 (contact with #4 was lost July 17).

Unprecedented

It was just a few years ago that it seemed the Moon was a curse. Most of the early Pioneer probes failed, with only Pioneer 4 a real success. Three our of nine Rangers were duds. Along comes Lunar Orbiter, every mission of which was more or less a triumph. The way has been paved for the first human beings to set foot on another world in a year or two.

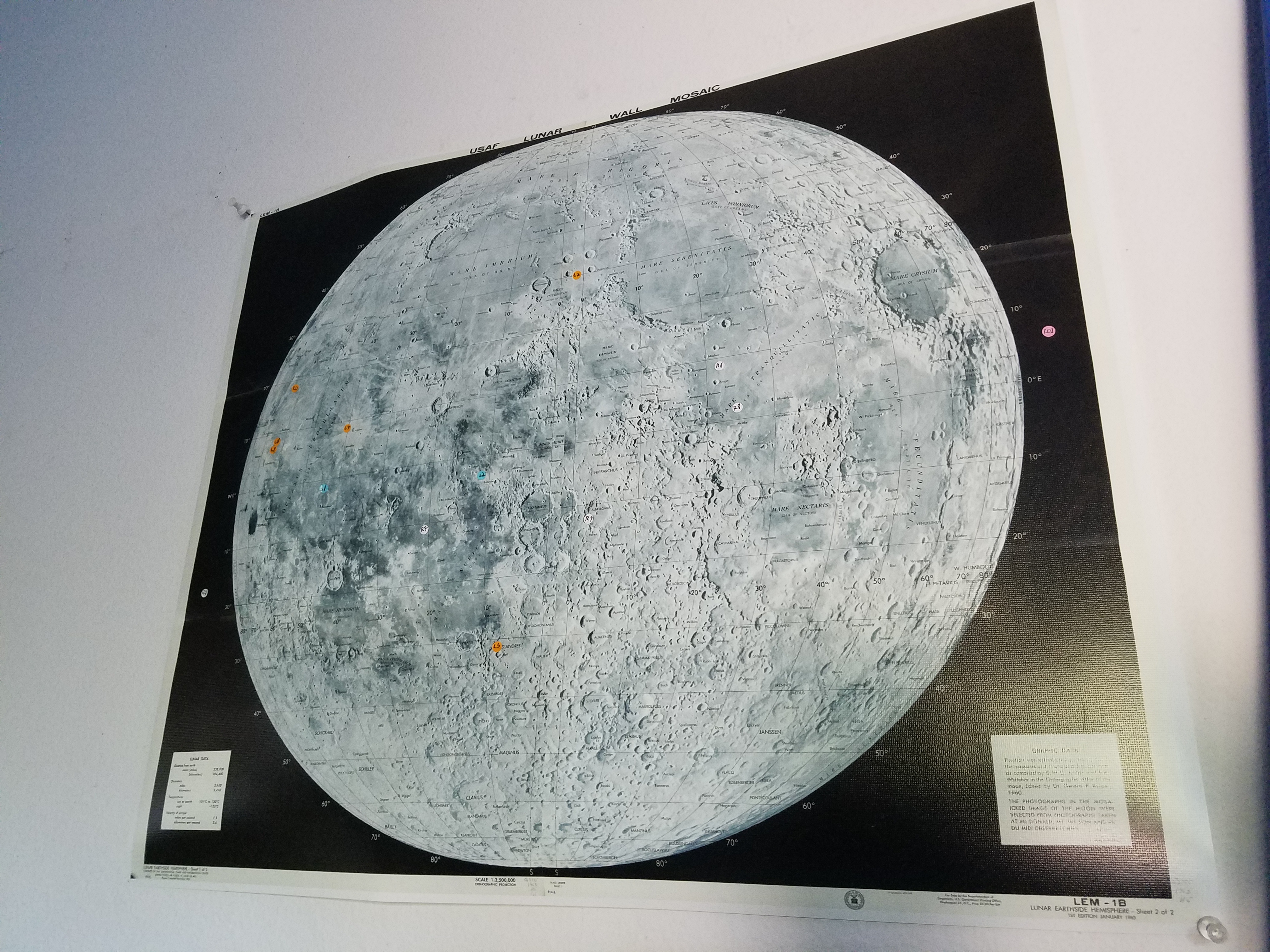

But beyond that, real science has been done. A few years back, my sister gave me a lovely 1963 map of the Moon, the most detailed possible at the time. I can't wait for a new map, based on Lunar Orbiter pictures, to come out.

I know what I want for Hannukah this year!

![[August 24, 1967] Up and Around (Lunar Orbiter)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/670824lunarorbiter-672x372.jpg)