by Gideon Marcus

Tunnel light

There have been a lot of happy endings recently. The postal strike is over, thanks to the government agreeing to an 8% raise for federal employees. Ditto the air traffic control strike. Nixon's third nominee to fill the vacant seat on the Supreme Court, 8th Circuit Court of Appeals Justice Harry Blackmun, isn't somewhere to the right of Ghengis Khan. The Apollo 13 astronauts made it back home by the skin of their teeth.

But of course, the old stories go on. The Vietnam war has grown to include Cambodia—if Domino Theory is to be believed, we'll soon be fighting in the streets of Canberra. Teachers are on strike in California; Governor Reagan says they're "against the children". And actor Michael Strong says you can't walk the streets of the nation's capital without a good chance of getting mugged.

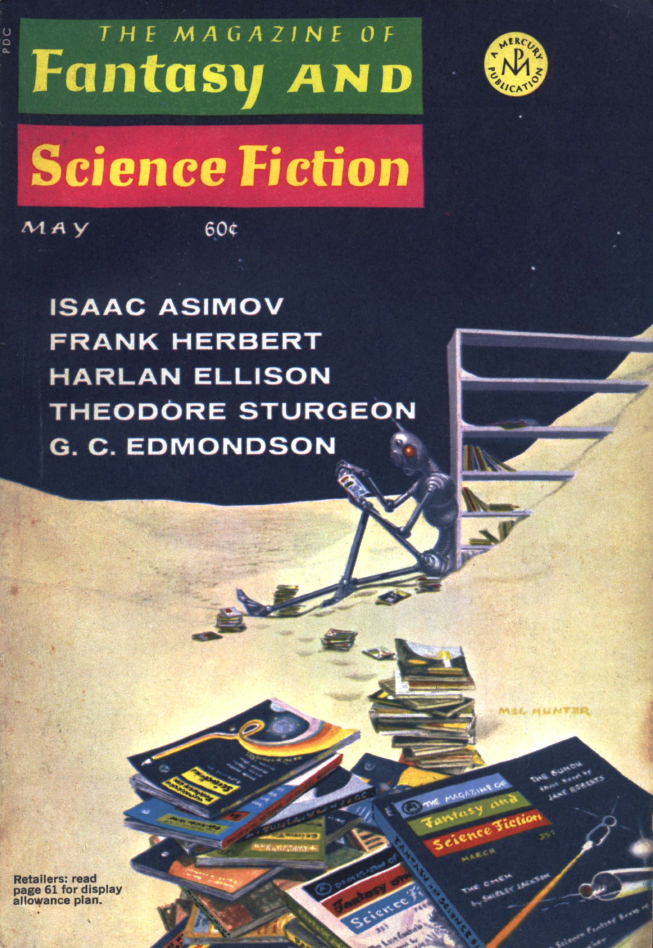

And so, it is appropriate that the latest issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction is a mixed bag. Some of it will thrill you, some of it will leave you cold. On the other hand, none of it will mug you.

The Issue at Hand

by Mel Hunter

Continue reading [April 20, 1970] Not the final quarry (May 1970 Fantasy and Science Fiction)

![[April 20, 1970] Not the final quarry (May 1970 <i>Fantasy and Science Fiction</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/700420fsfcover-653x372.jpg)