by Mx. Kris Vyas-Myall

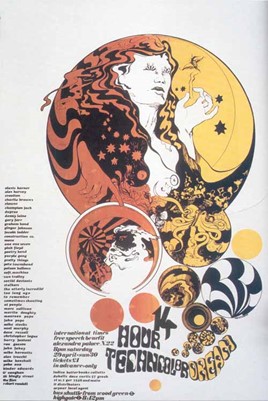

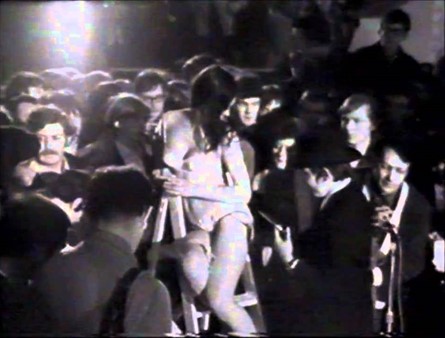

Last Weekend in London, the most happening party of the year took place, The 14 Hour Technicolour Dream.

In order to help raise funds for International Times legal defence fund, Alexandra Palace was hired out for an extravaganza of the most “out there” artists around. Throughout the whole of Saturday Night there were a wide array of different entertainments to enjoy.

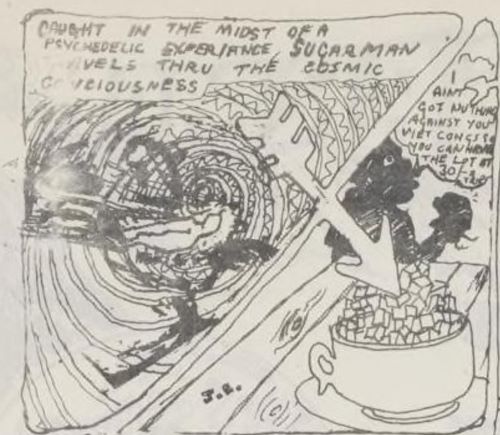

Whether that be the psychedelic music of Pink Floyd, the films of Kenneth Anger, the auto-destructive art of Yoko Ono or just Beatniks throwing flour bombs, it was an experience that London has never quite seen before. Quite a long way from the extended poetry reading at the Albert Hall less than 2 years ago.

With ads everywhere, from the underground papers to the up-market boutiques of Chelsea, it became the place to be seen with everyone from members of The Beatles to Warhol. From Dick Gregory to the near mythical Suzy Creemcheese.

Whilst some of the mods in attendance didn’t really dig the young men in long scruffy hair wearing cowbells or some of the interactive art, it has been hugely popular with an estimated 7000 attendees. There have been discussions of what to do with all the money, although a hitch that some of the tickets appear to have been stolen, so proceeds may come up short of what is expected.

With this new generation of flower loving beatniks (or ‘hippys’ according to the American press) coming up there is definitely a change in the kind of artistic expression they like. And one surprising thing they seem to enjoy is Marvel Superhero comics:

Getting Here From There

When Marvel’s superhero line began a few years ago there were two main ways to read them in the UK, neither of which were easy.

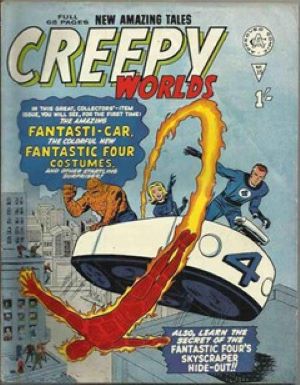

The first was via reprints from Alan Class. This company has several titles devoted to reprinting American comic strips. The problem with these is they would often be a pretty random selection of titles, considering these superheroes not really as ongoing stories, just the same as one-off horror and SF tales to sprinkle occasionally through issues. Also, at a shilling these are at the more expensive end of the comic book market, where around sixpence is the usual price.

The other was through direct import, predominantly via Thorpe & Porter. These, however, did not have wide distribution compared with British comics and, when the company went bankrupt last year, it was purchased by IND, National’s (AKA DC) distributor and the flow of Marvel imports slowed to a trickle.

So, acquiring these stories was a real challenge for UK readers. That is until another surprising source came through. One due to the success of British Comics superstar, Leo Baxendale.

A Non-Cowardly Lion

Starting in the early 50s Leo Baxendale began working for DC Thompson on The Beano, Britain’s top selling comic book (over a million issues a week, about the same as national newspapers like the Daily Telegraph). For it he created some of their best loved strips, such as Minnie The Minx, When The Bell Rings and Little Plum.

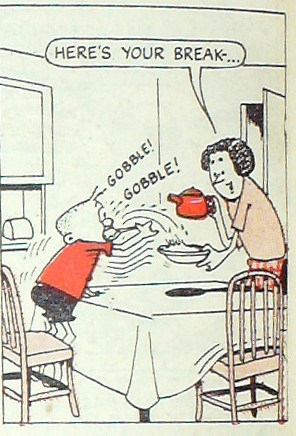

After leaving DC Thompson, Odhams hired him to create a new humour comic for them, the result was Wham! launching in 1964. Whilst containing some new ideas, it contained a number of very similar ideas from DC Thompson titles (e.g. The Beezer has The Numskulls, about the inner life of a child’s senses, Wham! has Georgie’s Germs, about the lives of germs on a dirty child).

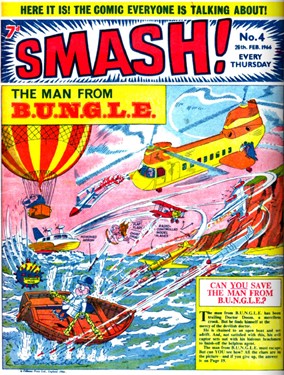

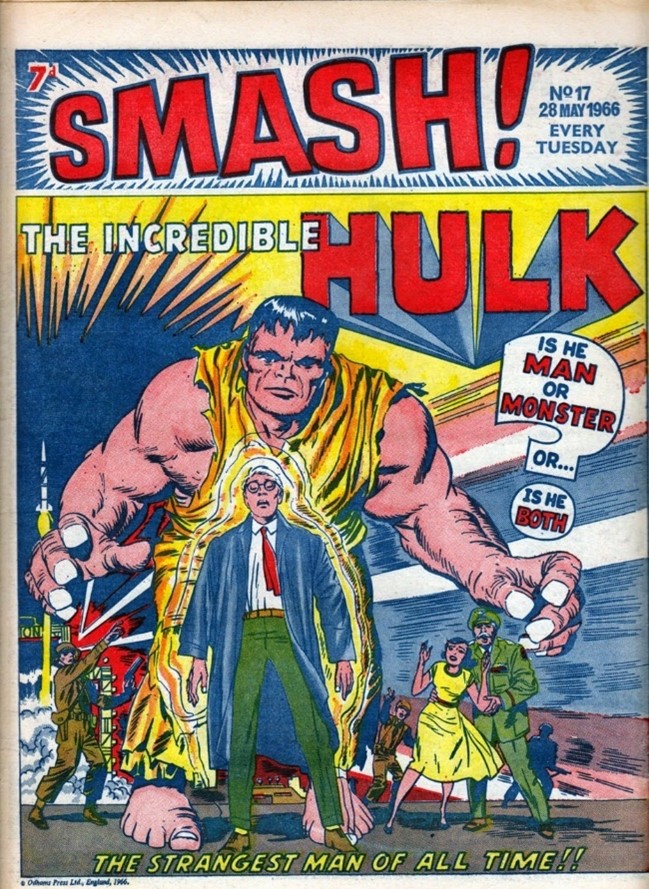

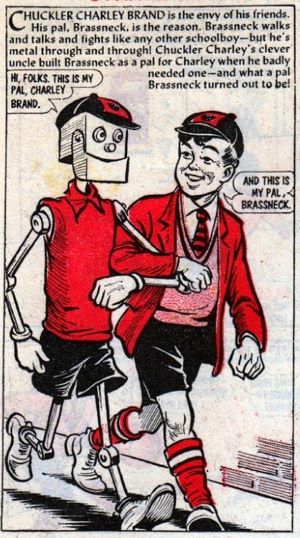

However, it was successful enough for Odhams to want a second title in the same style. This was Smash! which followed in early 1966 in much the same style, with the Minnie-esque Bad Penny and another microscopic strip The Nervs, along with parodies, such as The Man From BUNGLE.

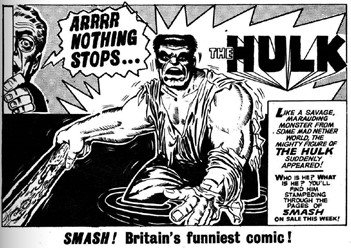

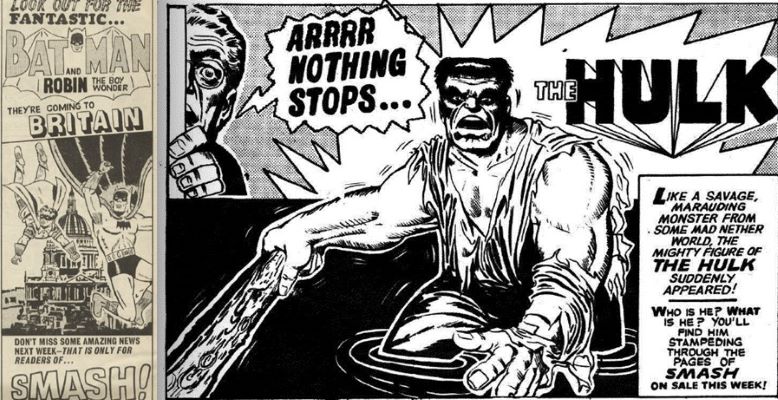

A few months in they began to import two American strips. The Newspaper version of Batman and Marvel’s The Hulk.

Hulk Smashes On To The Scene

I think it is important to start with the differences in the importation of these strips. The first, and most obvious point, is that British comics do not have many colour pages. Smash! itself only has them on the front cover (used for the first half of the Batman strip) and the back (currently occupied by surreal humour strip Grimly Feendish), and, even then, in a limited number of tones. As such all of the Hulk’s exploits are in black and white.

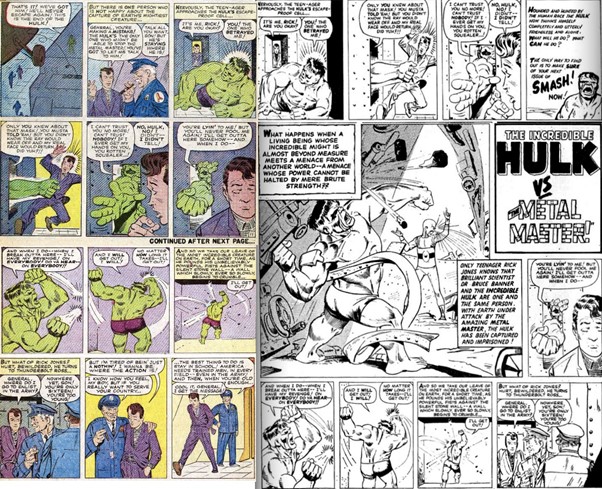

Secondly, as this is in the standard British weekly anthology style of comic book, it does not often have the space to reprint an entire story. As such they have to be broken up into multiple issues. At the same time, British comic dimensions are slightly different, so some panels have to be either rearranged or modified to fit.

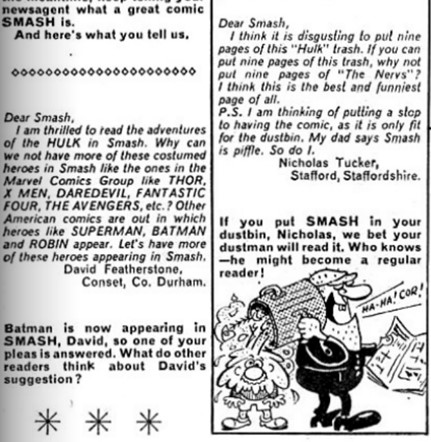

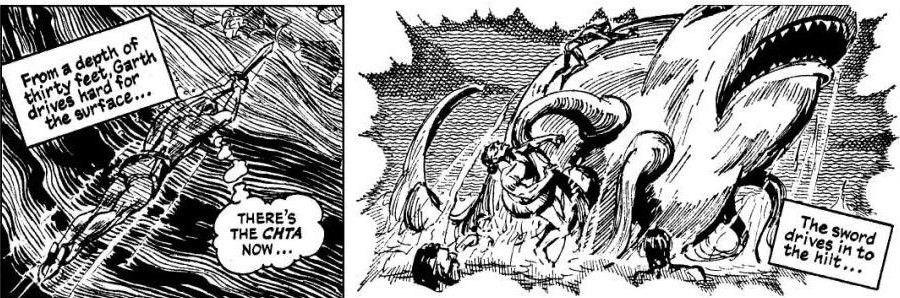

Whilst some readers did not appreciate their Baxendale style comedy being interrupted by superhero antics, in general the changes have been well received and Hulk continues to lumber on. Which leads to third difference: Odhams made the choice to follow the characters through their appearances as best as they can, regardless of what book they were originally published in. Which leads us to the arrival of The Fantastic Four.

(Flower) Power Comics

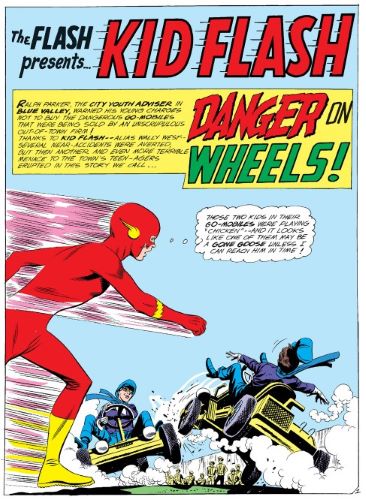

As Marvel readers in the US will probably recall, there was a period between the ending of Hulk’s own series and his continued strip in Tales to Astonish. Rather than simply stopping one and starting the other, they follow his continued exploits. Next is his encounter with the Fantastic Four, so they are the next to be imported. After an introductory story, the tales of them facing each other begin in Smash!, followed by The Fantastic Four appearing regularly in big-sister title Wham!.

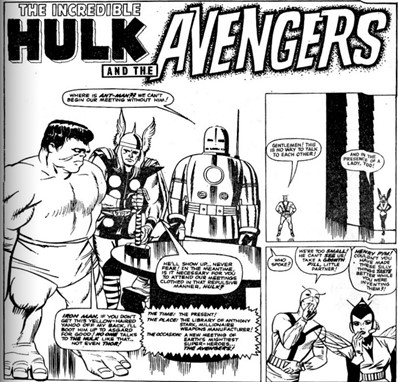

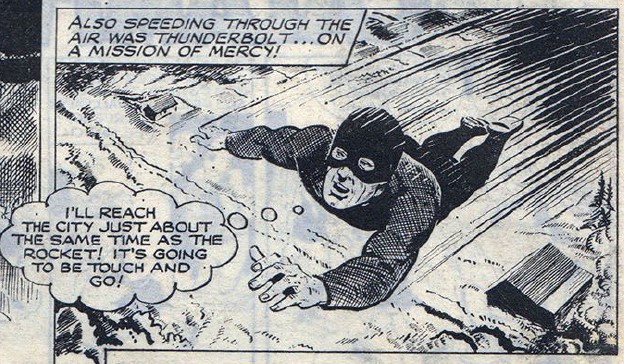

Next, he is on to The Avengers where things get particularly interesting. First off, these are rebilled as The Incredible Hulk and The Avengers (later V. The Avengers), to reflect the continuing adventures of Bruce Banner’s alter ego. However, what it also did was introduce readers to a whole range of characters they wanted to see more of.

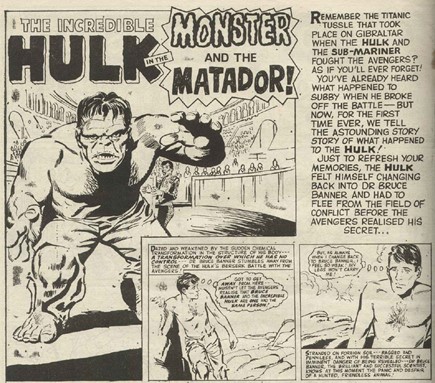

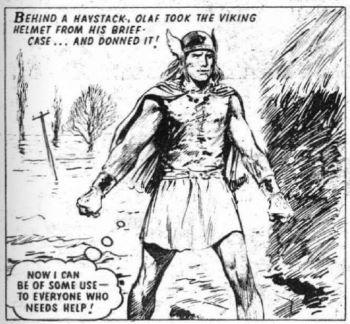

Secondly, there are gaps in the Hulk’s story between issues, so they have their own strips drawn to fill them in. the first of which explaining what happened to him after he goes into the sea near Gibraltar.

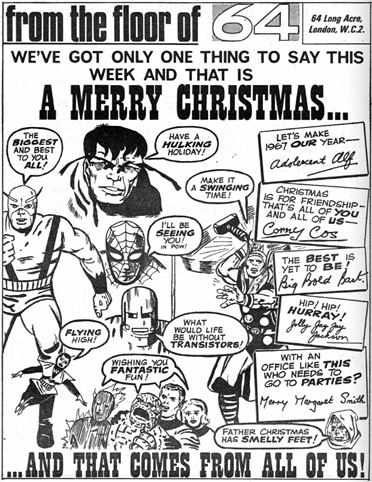

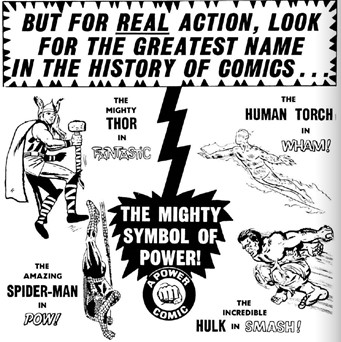

This combination of showing off the range of heroes available and willingness to play with exclusive material opened the floodgates, leading to new branding of them as Power Comics and the launching of three primarily superhero titles.

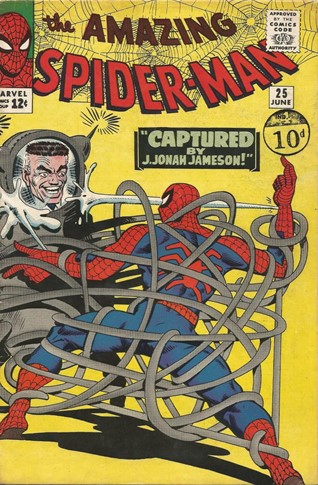

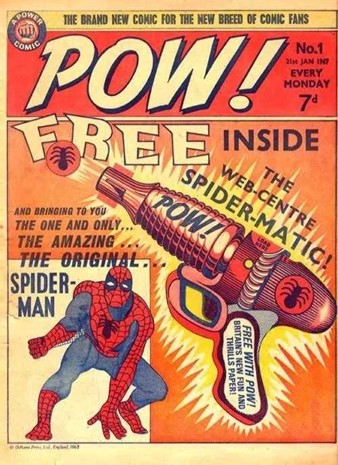

First, is Pow!. In this are two reprints, Spider-Man and Nick Fury (originally Agent of SHIELD but since replaced by Howling Commandos era). In between are a few forgettable humour strips and two new adventure strips, Jack Magic, about a magician’s assistant who is transported to the present day, and The Python, where two adventures fight snake men and their giant mechanical reptile.

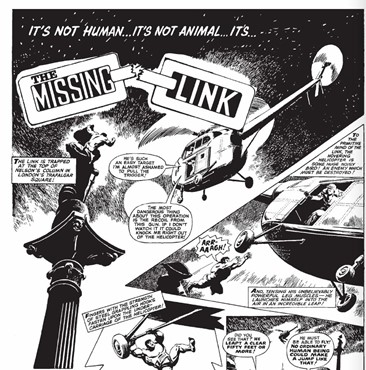

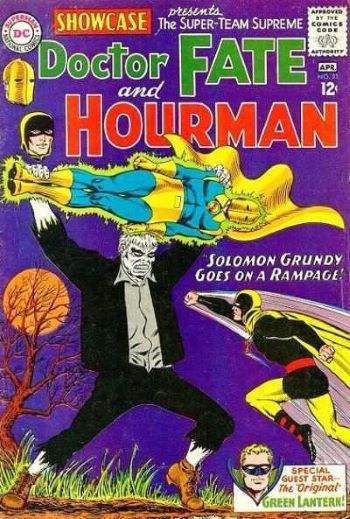

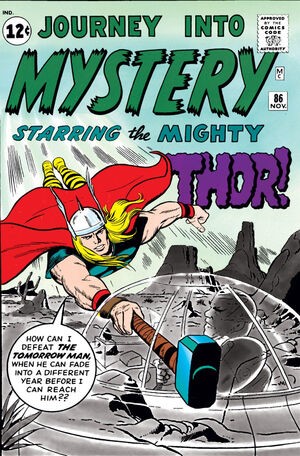

Then came Fantastic, this time containing three Marvel titles, Thor, Iron Man and The X-Men. In addition, they have their own superhero series, The Missing Link. Originally a Hulk like character menacing London King-Kong Style, he has recently got into a nuclear reactor accident which has given him super-intelligence and a normal appearance, whilst keeping his superhuman strength.

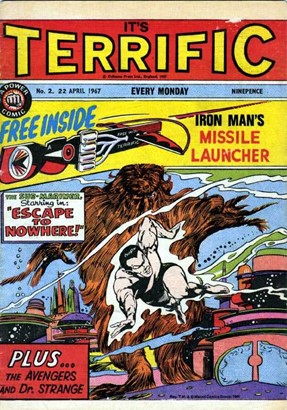

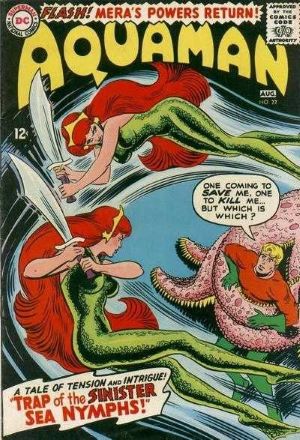

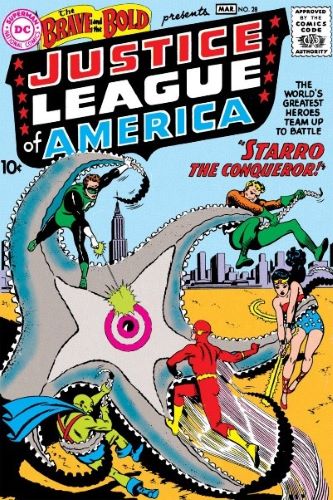

The most recent to debut is Terrific, which is entirely reprints, giving us the adventures of The Submariner, Dr. Strange and The (now Hulkless) Avengers. Plus occasional horror shorts from Marvel’s back catalogue in order to fill the space if the main stories run short.

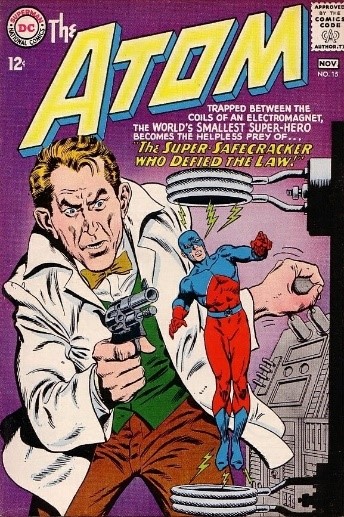

All of this means the majority of Marvel’s superhero line is now being reprinted in these “Power Comics”. With a recent announcement that Daredevil is in negotiation, this just leaves Giant Man, who I don’t see anyone crying out for, and Captain America, who might need some localization to work. Maybe he could follow GI Joe’s lead and become “Captain Action”?

The Power-House Period

Now, going back to my introduction, what we are seeing is the new generation of beatniks seem to love them. Reportedly a recent poll of Berkley students placed The Hulk as the 6th greatest man in the world (Dylan won, obviously) and I regularly see ads in British fanzines and underground presses for people seeking out copies of the American originals.

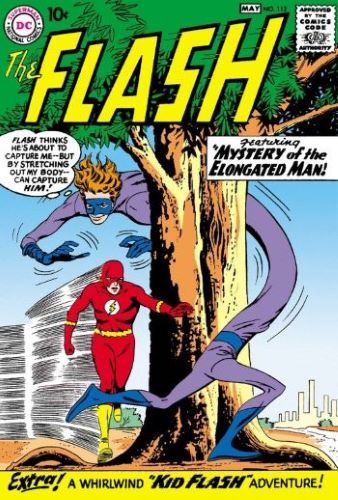

What is the reason for this? Some have cited some of the technical innovations with more serialization, crossovers and soap opera dynamics. However, many of these are elements already present in many British comics and certainly seen in more recent DC titles like Doom Patrol and The Legion of Superheroes.

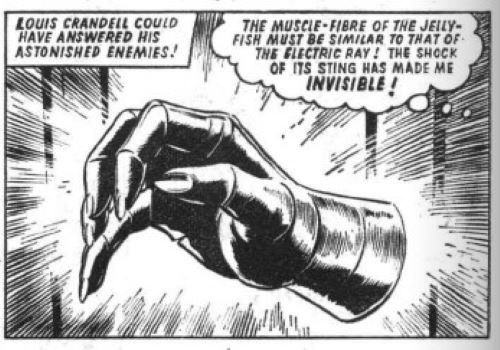

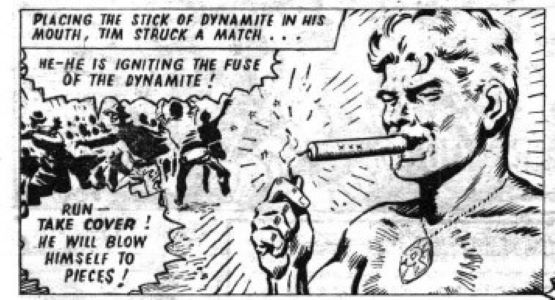

(from Dr. Strange and Fantastic Four respectively

I think the answer lies in the characters they are creating. The Hulk and the Thing are figures of great angst. Peter Parker and Johnny Storm are much more relatable teenagers than the richer but flatter Teen Titans. Nick Fury appeals to the Bond fans, whilst Dr. Strange is pure psychedelia. There are also regular smart uses of progressive politics, such as dealing with hate organizations or the existence of an advanced African society. A stark contrast of the excruciating message issues we get from other companies.

“It's a sign of the times, and a year ago I never could have seen it”

Until recently both Odhams and the British youth scene seemed mired in the past, with Eagle being a shadow of itself and extremely high-priced boutiques churning out the same modish styles for rich kids to dance to the same beat sounds since ’63.

Over the last year we have seen fascinating new life emerging, with the Americans trying to teach us Brits a thing or two. Let’s see if we can learn the lessons.

![[April 28, 1967] Tempest in a Teacup (<i>The Terrornauts</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Title-card-672x372.jpg)

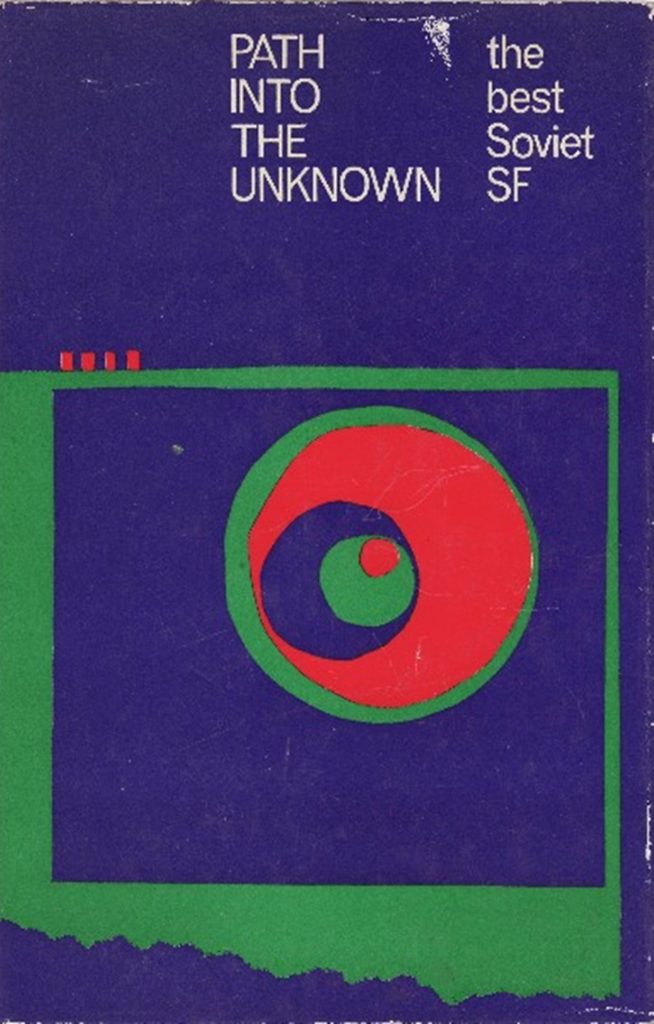

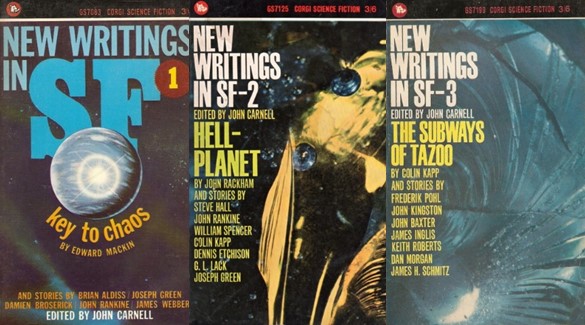

![[March 18, 1967] From Both Sides of the Curtain (<i>New Writings in S-F 10</i> & <i>Path into the Unknown</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Banner-672x372.jpg)

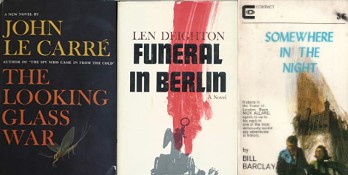

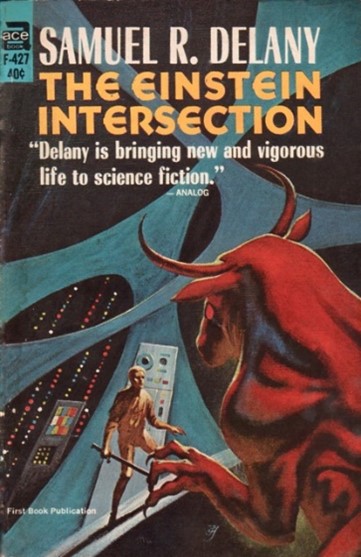

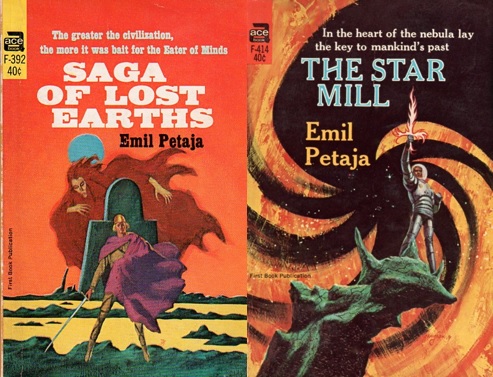

![[February 18, 1967] Six! Count them — Six! (February Galactoscope)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/670218covers-672x372.jpg)

![[December 10, 1966] Hot and Cold (December Galactoscope #1)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/661210covers-672x372.jpg)

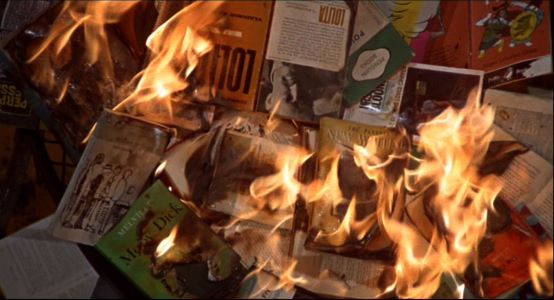

![[September 16, 1966] Is Censorship Heating Up? (Fahrenheit 451)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/F451-Poster.jpg)

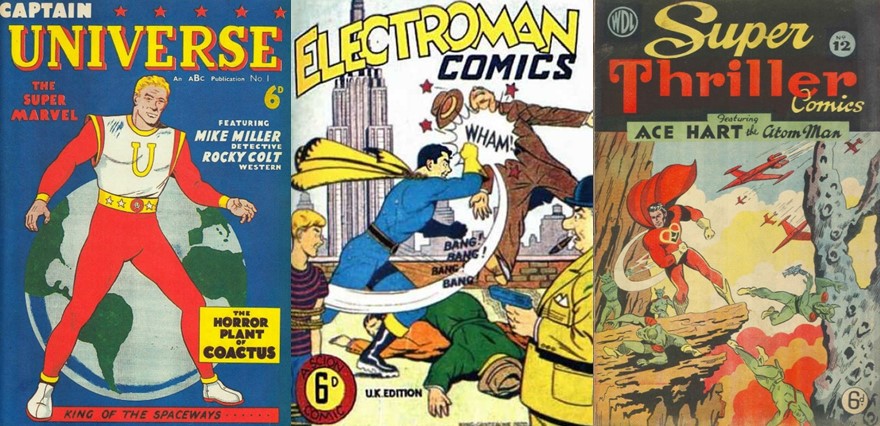

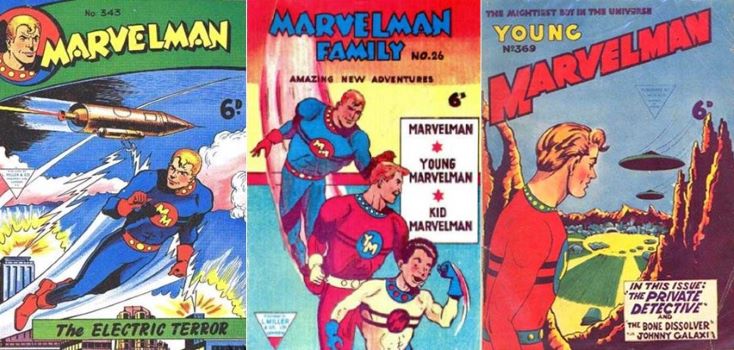

![[June 26, 1966] Justice League of Britain (New British Superhero Comics)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Superhero-Cover-Image-672x355.jpg)

![[June 12, 1966] Which Way to Outer Space? (New Writings In SF 8)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/New-Writings-in-SF8-Cover-259x372.jpg)

![[May 12, 1966] Equal & Opposite Reaction (<i>The Symmetrians</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Sym5a.jpg)

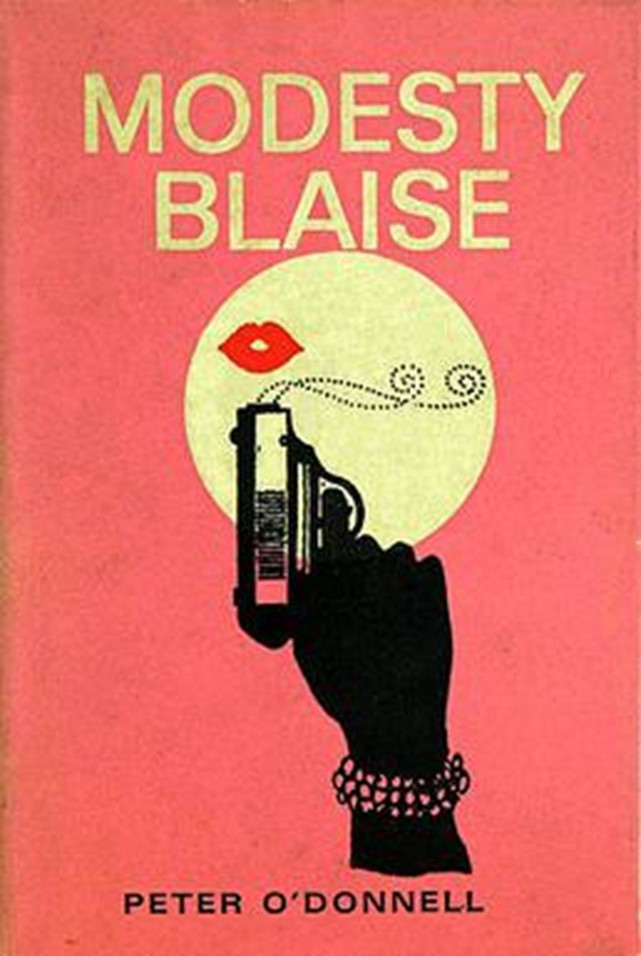

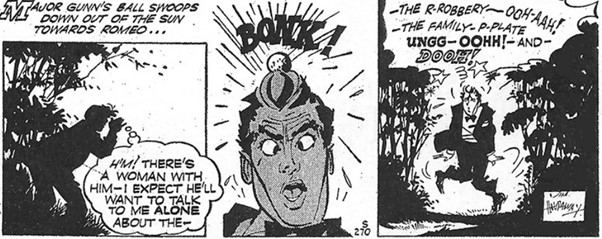

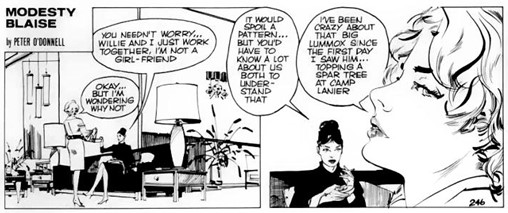

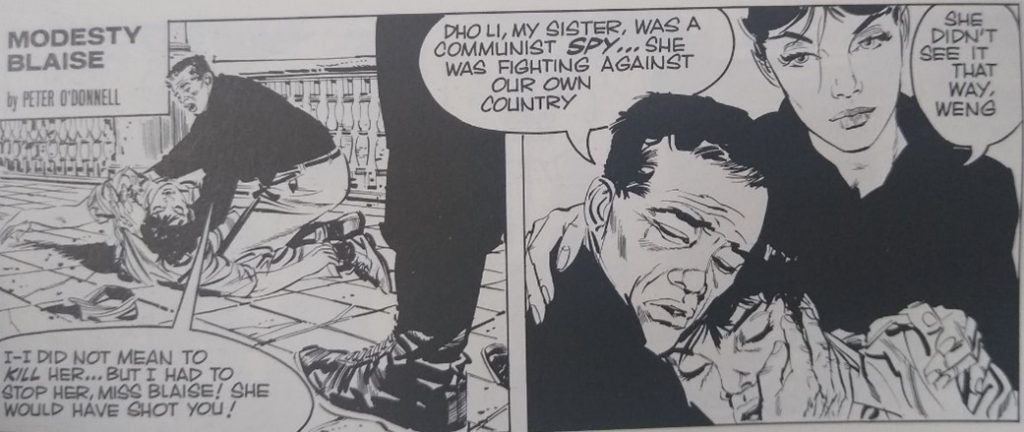

![[May 6, 1966] Blaise-ing Wreckage (<i>Modesty Blaise</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/MB16.jpg)