by Kaye Dee

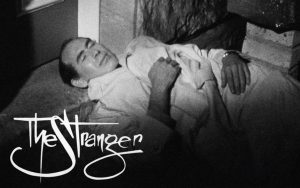

Back in April, I wrote about The Stranger, Australia’s first locally-produced science fiction television show. The second series completed its run on the Australian Broadcasting Commission (ABC) in late July, so this month I wanted to look at how the story of the Soshunites and their Earthly friends has played out across six new episodes.

The new series of The Stranger opens with the same credits sequence and eerie theme music, although the otherworldy script used for the title has been slightly modified for series two

The ABC Takes Another Chance

When the first series came to its dramatic conclusion, the Soshunites had been granted permission by the United Nations to leave Soshuniss, their moon-turned-spaceship, and settle on Earth. This could have been a suitably happy ending for the story. However, after taking an initial gamble with producing a children’s science fiction adventure for television, the ABC decided on a second bold step. The ratings success of The Stranger, and its popularity with adult audiences, encouraged the national broadcaster to refocus the new series towards an older age group, with a significantly larger budget and a prestigious family audience timeslot at 7.30pm on a Sunday night, making it Australia’s first locally-made prime-time science fiction series.

With Mr. G. K. Saunders again writing the script, all the original cast and production crew have returned for a story that is considerably more complex than the earlier series, involving international politics, intrigue and a ruthless business mogul planning to exploit the Soshunites’ arrival on Earth for his own profit.

Episode 1

Broadcast on Sunday 20 June, the opening episode of series two picks up immediately after the events at the end of the previous series: in fact, together the episodes could be considered a two-part story. The UN’s decision to allow the Soshunites to settle on Earth has been prematurely leaked to the press by a US Senator. Panic ensues, with newspaper headlines proclaiming that an alien invasion is imminent.

In Australia, Soshunite emissaries Adam Suisse (whose Soshunian name, we now know, is Sinsi) and Varossa await the return of Prof. Mayer, who has been acting on behalf of Soshuniss at the UN. Suddenly, the home of their hosts, the Walsh family, comes under siege by the press and television crews. Seeking to protect the aliens, Col. Nash, the Security chief, confines them in Adam’s former home on the grounds of St Michael’s School, with a police guard. While Nash has so far been friendly, his attitude begins to change when Adam, rankled by what he sees as imprisonment (he clearly doesn’t understand the persistence of newshounds!), informs him that there has been a change of leadership on Soshuniss.

In one of Mr, Saunders’ characteristics twists, the female Soshun, whose policy was that her people would only settle on Earth if invited, has been replaced by a new male leader. This new Soshun is determined to establish his people on Earth, and when Adam says he agrees with this policy, Nash begins to suspect that perhaps the Soshunites are not as peaceful as they have portrayed themselves up till now.

The hypnotic stare of a Soshunite pilot as he uses his mind-control abilities to kidnap Peter Cannon!

Meanwhile, Peter Cannon, one of the three teenage children who befriended Adam and the Soshunites in series one, secretly uses Adam’s space radio to contact Soshuniss, trying to advise the Soshun of the situation. Unaware of the change in leadership, when a Soshunian spacecraft arrives Peter approaches it. The pilot then induces him to board the ship using the Soshunites’ mind-control abilities…

Episode 2

In New York, Prof. Mayer receives a visit from Rudolph Lindenberger, the world’s richest man. (Imagine, he claims to be a billionaire! And even though a US billion is considerably less than a British billion-that’s still a fantastical amount of money to be anyone’s personal fortune). Lindenberger tries to persuade Mayer that, as an American, he must use his influence with the aliens to ensure that their scientific knowledge is handed over to the United States. Mayer believes that Lindenberger is a misguided patriot, but his son Edward smells a con and believes Lindenberger is looking to line his own pockets.

Arriving on Soshuniss, Peter is taken to the new Soshun and learns that the Soshunites are now desperate to land on Earth because their computers have determined that there is no other suitable planet that they can reach. The Soshun tells Peter that his people have a powerful weapon that will be used if they are not given permission to land. With Adam and Varossa still on Earth, Peter has been kidnapped to be held as a hostage to ensure their safety.

Lindenberger's aide, Blake, tries to pump Edward Mayer for information about the Soshunites as they fly to Australia

Once Mayer and his son, Edward, arrive in Australia, plans are made to move Adam and Varossa to the Parkes Radio Telescope, in country New South Wales, which will be turned into a space communications facility. Joining them, will be the Mayers and teenagers Bernie and Jean Walsh. Along with Peter, these are all the people who have been to Soshuniss. This will keep them safe from the reporters, but is there another motive?

Adam has now decided that he does not trust Nash. Using their mind-control powers, he and Varossa subdue their police guards and escape. Varossa is shot and captured by another police officer, but Adam jumps into Nash’s car and uses his hypnotic ability to make the driver obey his will.

Episode 3

Varossa is in hospital, recovering from his wounds, although Nash keeps this secret from Mayer and the Walshes. The Security chief discovers that no-one can remember anything after being under the Soshunites’ mind control, including Nash’s driver: Adam has disappeared, his whereabouts unknown. Nash proceeds with his plan to move everyone else to Parkes. Although they evade the pursuing newshounds, Lindenberg’s henchman, Blake, realises where they must be heading. Adam, too, is also travelling to the vicinity of Parkes.

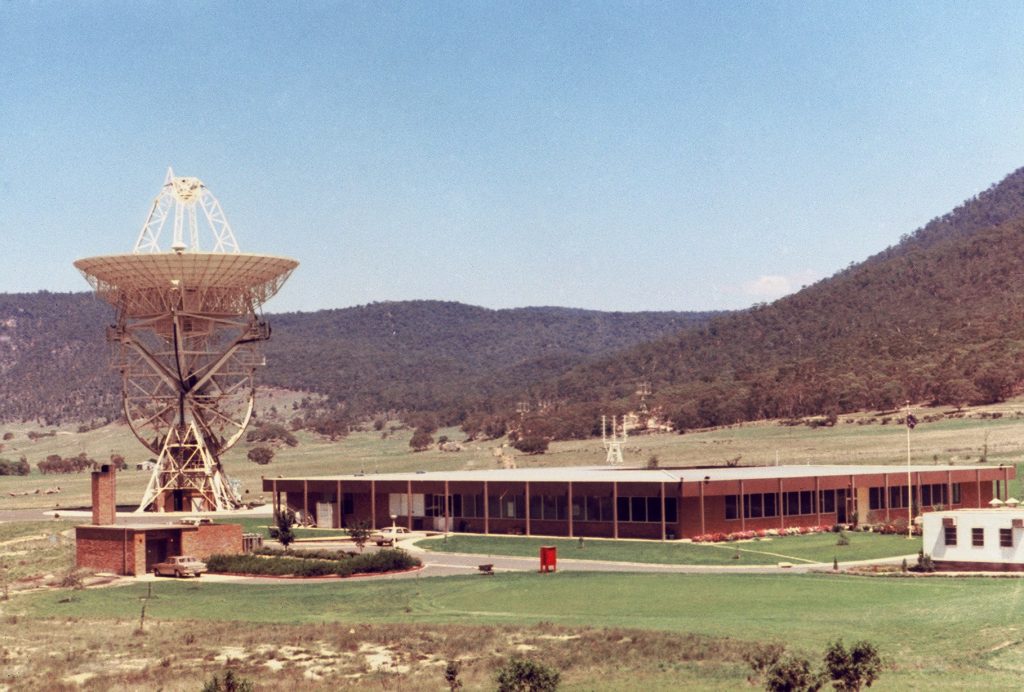

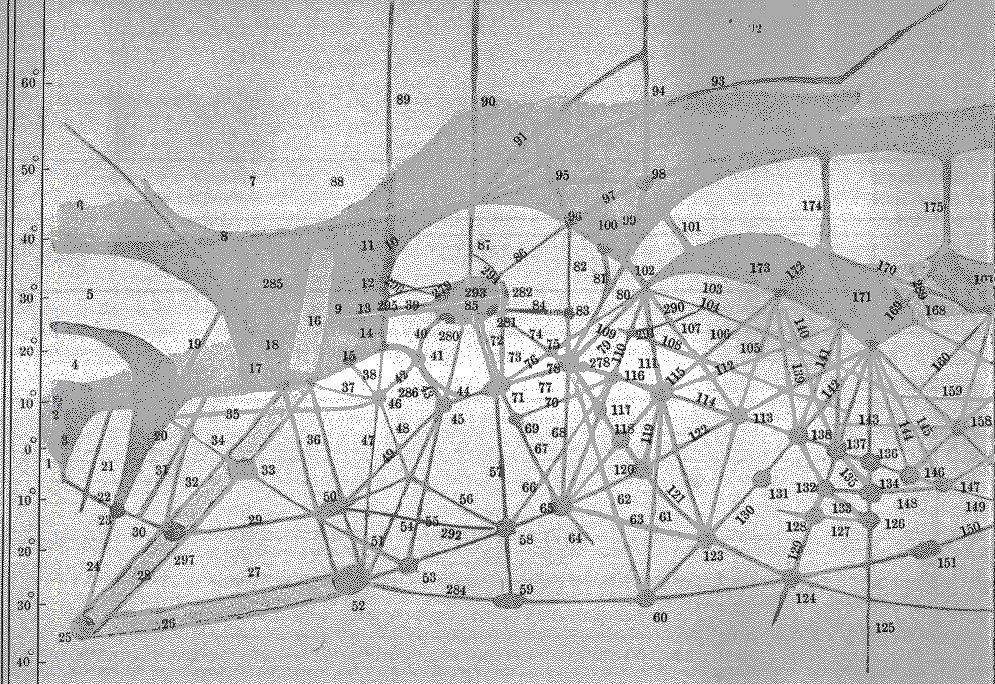

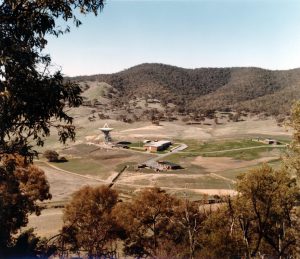

The Parkes Radio Telescope is Australia's most significant scientific instrument and the largest fully-steerable radio telescope in the world. It features in the opening credits of both series of The Stranger and plays a prominent role in series two. A pity the Soshunites destroy it in Episode 5!

Visiting the General Manager of his Australian subsidiaries, Lindenberg reveals that his plan is to make sure that the Soshunites are settled somewhere under his control. He intends to exploit their advanced knowledge to generate huge profits for his businesses – “in the billions”! Edward Mayer was right to distrust his motives.

On Soshuniss, the Soshun decides to demonstrate the Soshunites’ advanced knowledge. Peter is placed under mind control and forced to write a letter to the Prime Minister of Australia. His arrival in Canberra from Soshuniss, it says, will be proof of the power of the Soshunites. Meanwhile, Nash and the others have now arrived at the radio telescope, which is searching the skies for signals from Soshuniss in orbit. As the episode ends, they think they have found it!

Searching for Soshuniss. Professor Mayer joins senior telescope operator Dr. Scott in the control room of the Parkes Radio Telescope

Episode 4

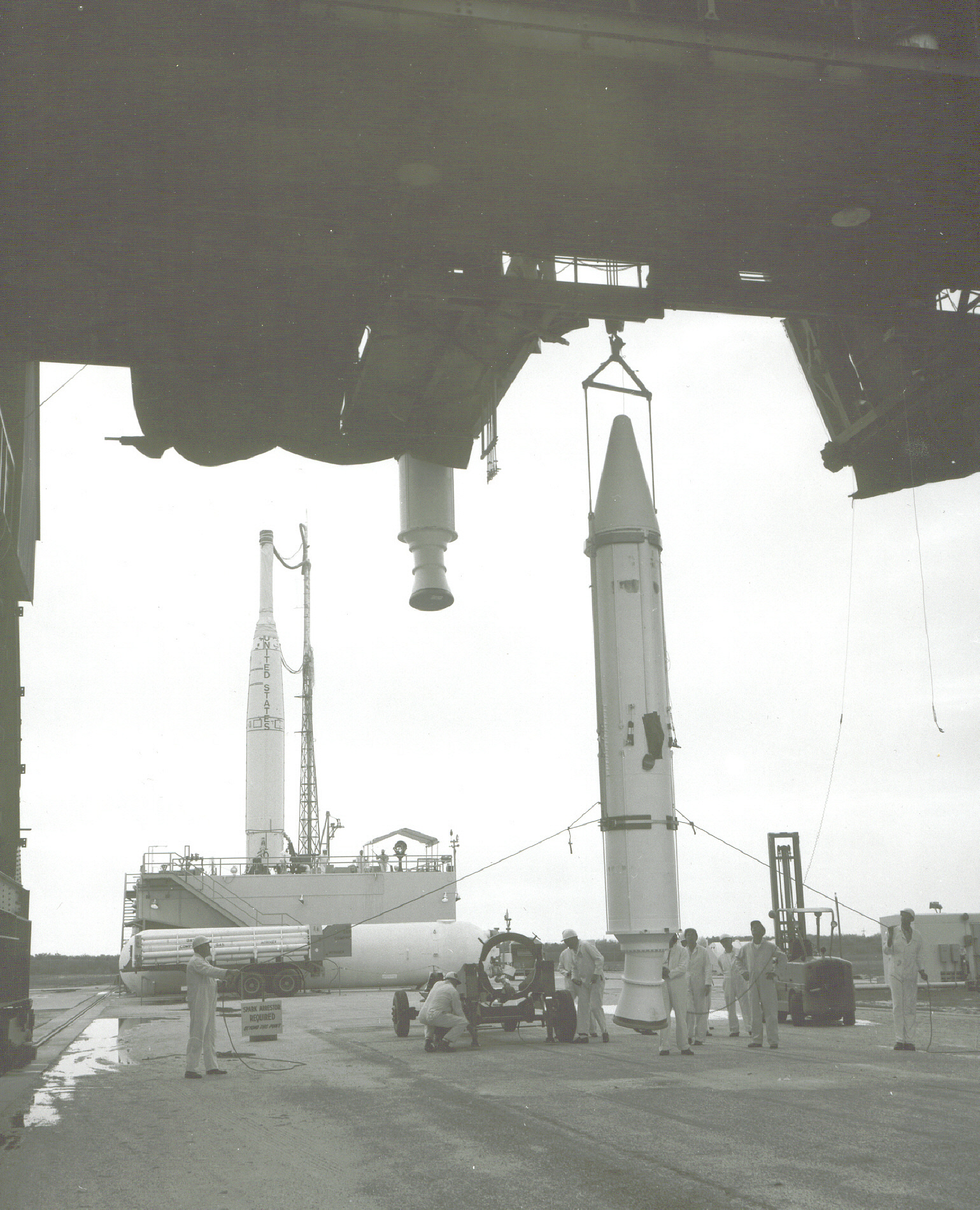

With Soshuniss located, Mayer learns that there is a plan to “fit Moon rockets [presumably American] with nuclear warheads” if no peaceful agreement can be reached with the Soshunites. Meanwhile, Jean has experienced a strange dream that Adam wants her to collect a letter from the post office in a village not far from Parkes. Convinced it is a telepathic message from the Soshunite, Jean escapes secretly from the living quarters at the radio telescope and retrieves the letter. Unfortunately, Lindenberg’s assistant, Blake, who has now arrived in Parkes, manages to tail Jean, and overhears when she calls the boys to tell them where Adam is hiding.

When the three teens reach his hideout, they realise that Nash has been less than truthful, as they know nothing about Varossa’s shooting when Adam enquires about him. Adam asks the youngsters to bring him his radio, which has been brought to the telescope’s lab for study, so that he can contact a Soshunian spacecraft. Blake has been eavesdropping and phones Lindenberg with the news. The ruthless businessman immediately flies to one of his company properties near Parkes.

Even though Adam hides in an old country showground, the persistent Blake manages to track him down

Mayer, as yet unaware there is a new, militaristic Soshun, tries to convince Nash that the Soshunites are completely peaceful. However, his arguments are destroyed when Peter is discovered in a deep coma, of a type unknown to Earthly medicine, in the private Members Courtyard at Parliament House. A threatening letter from the Soshun to the Prime Minister is clutched in his hand, delivering an ultimatum: Earth must allow the Soshunites to land, or they will use their weapon.

Meanwhile, Jean, Bernie and Edward take a risk and enlist Mayer’s help to retrieve Adam’s communication device. Mayer is shocked to learn that, as with the information about the new Soshun, Nash did not inform him that Varossa was shot and captured.

Episode 5

As Mayer attempts to obtain the Soshunian radio, one of Lindenberg’s henchmen tries to steal it at gunpoint from the radio telescope’s lab. In the ensuing confusion, Bernie manages to grab the device and races up the through the telescope building chased by Blake. Desperate to escape, he climbs up onto the telescope’s antenna and makes his way precariously across the dish surface, still pursued by Blake. Suddenly the antenna begins to tilt alarmingly, and they both begin to slide.

The radio telescope operators have realised Bernie is in danger and moved the antenna so that he can slide safely down the surface of the steeply tilting dish and leap off as its rim nears the ground. Blake on the other hand, is left clinging for his life on the elevated side of the antenna. Dr. Scott, the senior telescope operator, then sneaks down to the lab and coshes the gunman holding Mayer and the others at bay. The radio telescope personnel help Blake down from the dish, but he and the gunman escape. Like Mayer, Edward and Jean, Blake follows after Bernie, who is already on his way to Adam with the space radio. Meanwhile, Bernie and Jean’s father has arrived at the telescope, after hearing news of Peter’s mysterious appearance in Canberra.

Hanging on for dear life! Lindenberger's henchman, Blake, clings to the tilted dish of the Parkes radio telescope during his pursuit of Bernie. This scene was actually filmed on the telescope

Mayer tells Adam what has happened to Peter and the three teens are shocked at this ruthless move by the Soshun. Mayer also decides to divulge the secret information about the plans to attack Soshuniss with nuclear weapons. To persuade the Soshun that the scientific community and most people on Earth are of goodwill and would welcome the Soshunites, Mayer offers to travel to Soshuniss on the spacecraft that is coming to collect Adam, to act as a human shield for the Soshunites.

Blake secretly records this conversation. When Lindenburg hears it, fearing the collapse of his plans to exploit the Soshunites, he devises a new strategy. Blake will kidnap Adam and transport him to a private island owned by Lindenberg, off the east coast of Australia. It has facilities large enough to house the entire Soshunian population (numbering just 300). Adam will be persuaded to invite the Soshunites to settle there in secret, so that they will be safely away from Soshuniss if it is attacked – and completely under Lindenberg’s control.

As revenge against Mayer for not falling in originally with his plans, Lindenberg also decides to use Blake’s recording to convince Nash that the professor is a traitor who has betrayed the Earth’s defence plans.

Nash’s Security team, Blake and his henchman, Walsh and the Soshunian spacecraft all arrive at Adam’s hideout at the same time and chaos ensues. Blake kidnaps Adam, who escapes using his hypnotic powers. Nash shoots Mayer in the leg to stop him boarding the Soshunian spacecraft, which hastily departs without either Mayer or Adam.

Episode 6

The final episode of the series is action-packed! Thinking Adam safe, the youngsters have returned to the radio telescope, but Nash arrests Adam, Mayer and Walsh. As they stop at Lindenberg’s farm for medical assistance to the professor, it becomes clear that the Security chief no longer trusts the businessman and now suspects his motives. Mayer persuades Walsh to escape and make a dash to Canberra. He must convince the Prime Minister that the threat from the Soshun is real. If the Soshunites are refused permission to settle, they will crash their moon-ship into the Earth: this is their weapon! Since they will be condemned to a lingering death wandering in space if they cannot land, they have nothing to lose.

Nash takes Adam to the radio telescope, where Bernie, Jean and Edward are now also under house arrest. When Adam realises that the antenna is being used to track Soshuniss so that it can be targetted by the nuclear-armed rockets, he secretly radios the Soshun. High-powered signals from Soshuniss destroy the telescope’s control system, rendering it useless.

Following Walsh’s meeting with the Prime Minister and the destruction of the radio telescope, Nash, Adam and Mayer are summoned to a meeting in Canberra. Dr. Kamutsa, the UN Secretary General’s personal representative, has also arrived. The Prime Minister has astutely realised that the current situation with Soshuniss has arisen from confusion since the initial information leak. He wishes to send Dr. Kamutsa to Soshuniss to discuss a “peaceful and harmonious” resolution and indicates that he already has a search underway for an area in Australia where the Soshunites can settle.

When Adam contacts the Soshun, the leader insists that Bernie, Jean and Edward, whom he trusts, be sent to Soshuniss as emissaries and hostages, to demonstrate the good faith of the Earth. It is eventually agreed that Dr. Kamutsa will accompany the children as an advisor and they are all transported to Soshuniss.

Upon arrival, Jean uses a ploy to persuade the Soshun to send medical aid to Peter, who is still in hospital in a coma. The Soshunite leader agrees and negotiations begin. Meanwhile Lindenberger makes a final attempt to gain control of the Soshunites, by publicly offering his private island as their new home – to which he will have access as the owner. However, Mayer and the Prime Minister adroitly outmanoeuvre the businessman, who is trapped into donating his island freely to the Australian Government: it is then placed under UN administration as the Soshunites’ new home.

Welcome to Earth. The Lord Mayor of Sydney formally welcomes the Soshun and his entourage to the Earth and Australia in front of Sydney Town Hall

With a resolution to the Shonunite’s desire to settle on Earth, and Varossa and Peter now out of hospital, Mayer reveals to Adam that he deliberately overplayed the Soshunite threat to crash their world into the Earth: he knew that Earth’s gravity would actually break up the spaceship-moon before it could strike the planet. Adam confesses in turn that the Soshunite’s strategy was all a tremendous bluff. Not only did they know that Soshuniss would be unable to destroy the Earth, they were so lacking in power that they were, in fact, unable to break the spaceship-moon out of its orbit around the Earth. The Soshunites would have died in orbit if their gambit failed and they were prevented from settling on our planet.

The story ends with a grand civic reception at the Sydney Town Hall, in which the Soshun and his people are welcomed to the Earth and Australia. In the final scene, Adam and Varossa depart from the steps of the Town Hall in a small Soshunian spacecraft, flying across Sydney Harbour and out to sea – towards their new home….

A Successful Transition

To judge from its ratings and the generally positive response from the television critics, the ABC should be satisfied that its experiment in prime-time science fiction television has paid off. Certainly, my sister’s family were engrossed, and even though I detected a few holes in the plot and more than a few holes in the science, I give Mr. Saunders full credit for creating a complex, multi-faceted story that turned the children’s adventure of the first series into an exciting family thriller. The story built and maintained its tension and air of uncertainty well, especially with the mistrust created by the multiple twists of Mayer’s bluff and Soshunites’ desperate double bluff. It also included moments of wry Australian humour to appeal to adult audiences, with jibes at bureaucrats and politicians, the military mindset, big business and even our “great and powerful friend”, the United States.

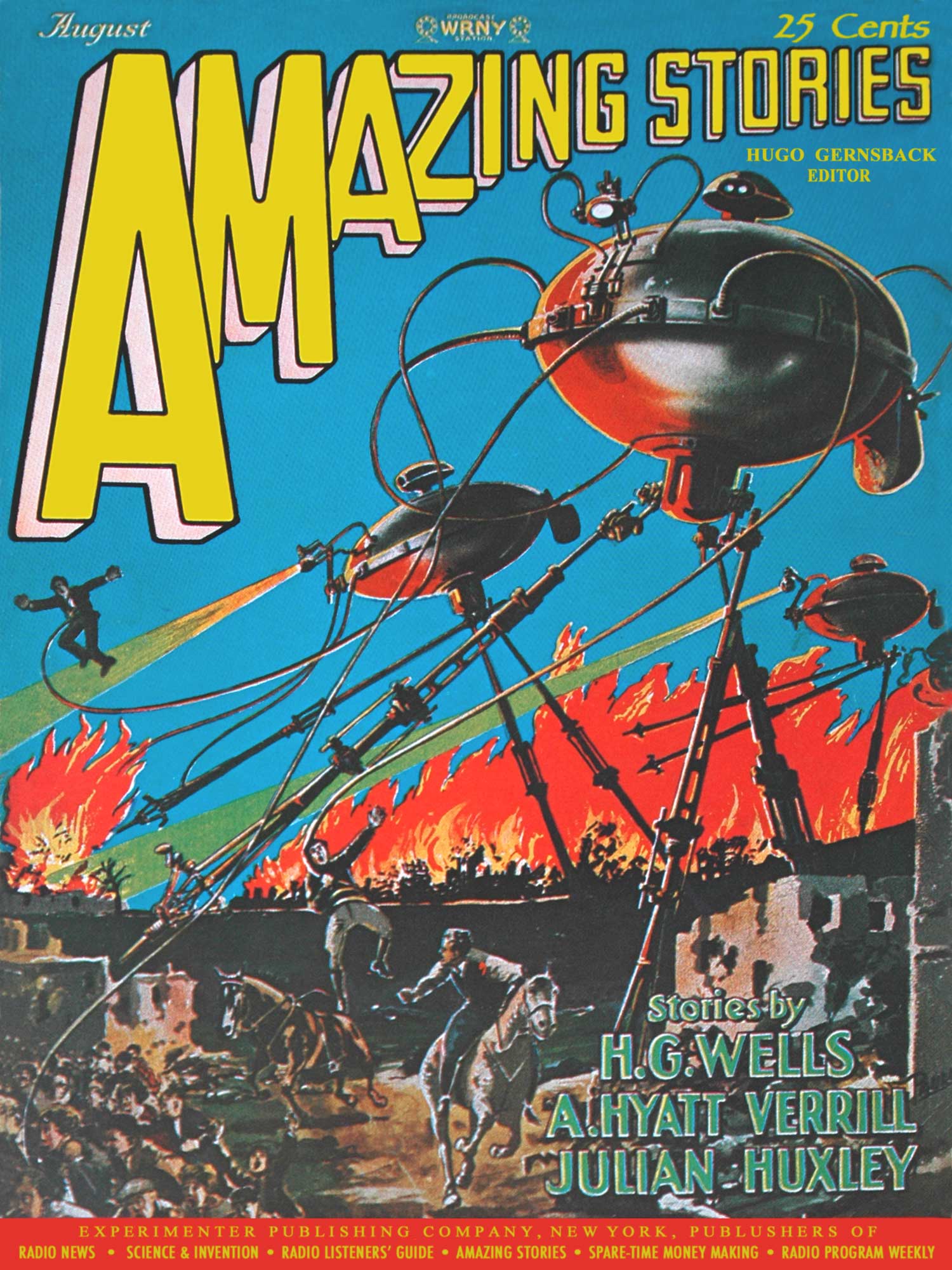

War of the Worlds! The fear of an alien invasion that generates tension in series two of The Stranger is highlighted in this preview article in TV Times

This series’ switch from the juvenile to family/adult category certainly gave more scope for the storyline, enabling it to move beyond the purely Australian focus of series one, to a more international outlook. Particularly interesting is the inclusion of the character of Dr. Kumatsa, a black African diplomat (played by American Negro actor Mr. Ronne Arnold, who has recently decided to live in Australia) as a representation of the role that the newly independent nations of Africa may one day play in the world.

Location, Location, Location

The noticeably higher budget for the second series, enabled producer Mr. Storry Walton to indulge his love of location filming. The Canberra scenes were filmed in Parliament House itself. Prime Minister Menzies even gave his personal permission for the scenes involving the Australian Prime Minister (played with suitable gravitas by veteran Australian actor Chips Rafferty) to be filmed in the private Prime Ministerial offices. Similar official approval was granted for filming at the Sydney Town Hall, which required the construction of a mock-up Soshunian spacecraft at the top of the forecourt staircase, as part of excellent special effects sequences showing the arrival of the Soshun and departure of Adam and Varossa to inspect the Soshunites’ new home.

Flying saucer lands at Sydney Town Hall! The imposing entrance to this iconic Sydney building is transformed into a set for location filming in the final episode of The Stranger

Various other outdoor scenes were filmed around Sydney, the Blue Mountains and Parkes, but ironically, the situation with the Walsh home was reversed. Although the original scenes of Headmaster Walsh’s house in the first series were filmed at a private home, to minimise disruption to the generous owners the house was faithfully replicated in a studio for the remainder of series one and series two.

The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) also gave unprecedented co-operation, presumably in return for the undoubted publicity it provides for the agency. The chase across the Parkes radio telescope in Episode 5 took place, not on a studio set, but on the telescope itself, which was manoeuvred as required for the filming. Actors playing the roles of telescope staff were even permitted to be filmed at the actual controls of the multi-million pound instrument. As with the first series, the CSIRO also provided general scientific advice to the production, which even found its way into some of the dialogue with reasonable accuracy.

The Future?

The sale of the first series to the BBC means that those of you in Britain should be seeing it within the next twelve months, and a sale of the series to the US is also nearing finalisation. While the second series has drawn the story of the Soshunites’ search for a new home to a satisfying conclusion, the ending still leaves open the possibility of a third series. It would be interesting to see how our alien friends cope with the challenges of living in, and adapting to, a new world. I guess only time will tell if the ABC decides to take on another challenge with science fiction television.

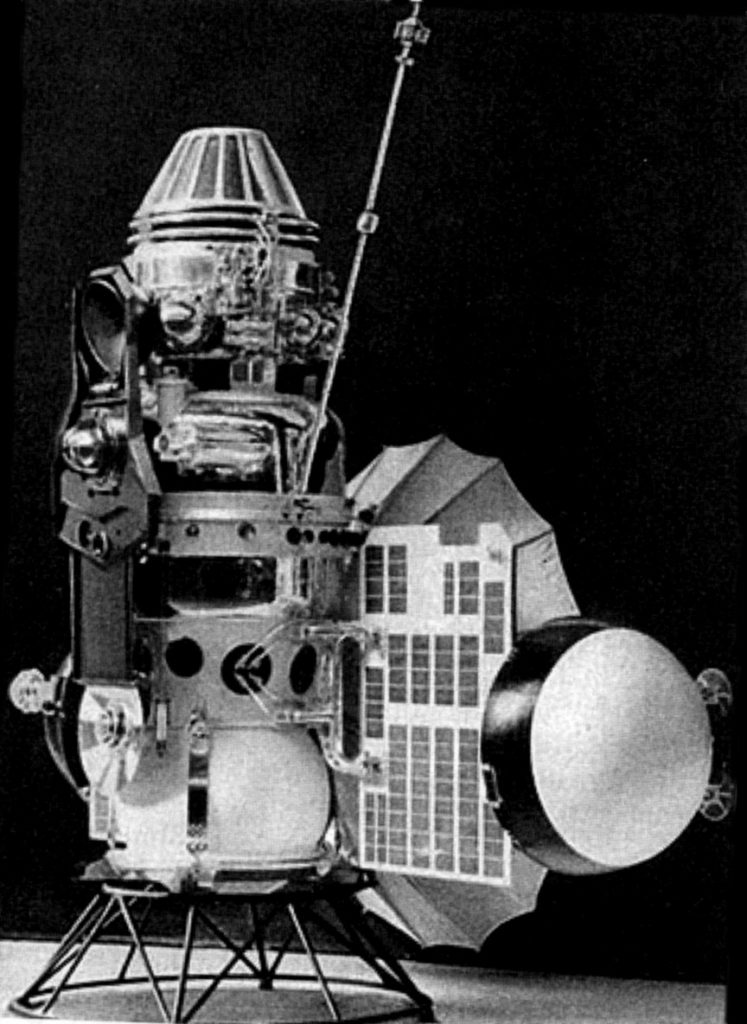

![[November 22, 1965] Keep on Exploring (Explorer-29 and 30 and Venera-2 and 3)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Venera_2-672x372.jpg)

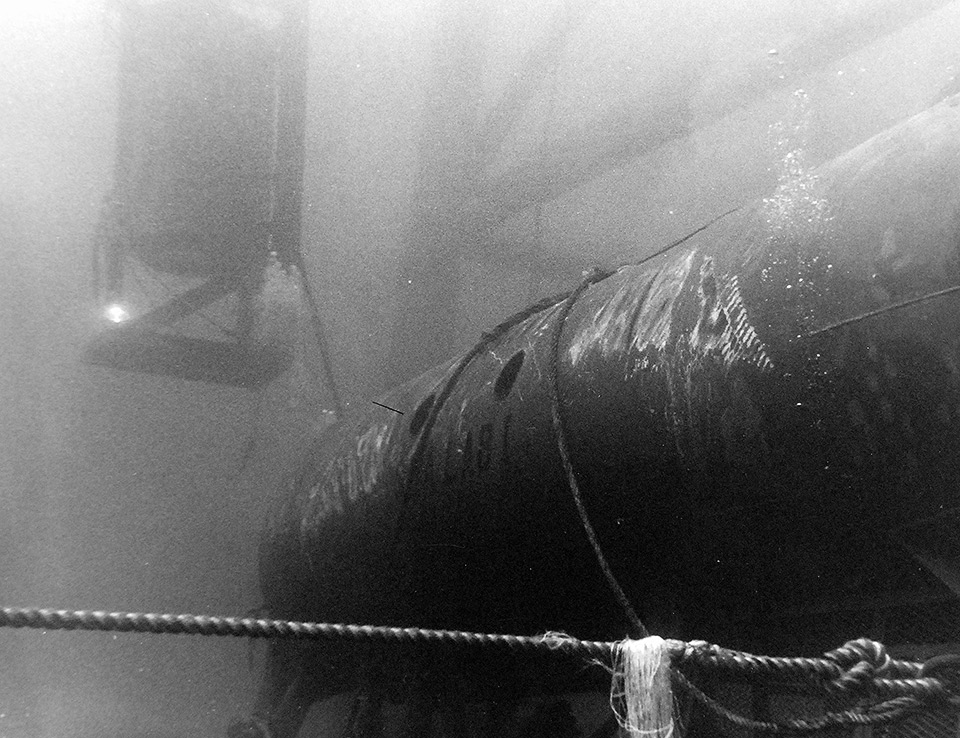

![[October 14, 1965] Taking a Deep Dive (the SEALAB project)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/SEALAB_II-672x372.jpg)

![[September 8, 1965] Still a Stranger in a Strange Land (<i>THE STRANGER</i> SERIES 2, AUSTRALIAN TV SF)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/The_Stranger-5.png)

![[July 20, 1965] No War of the Worlds After All? (Mariner IV reaches Mars)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/mariner04-640x372.gif)

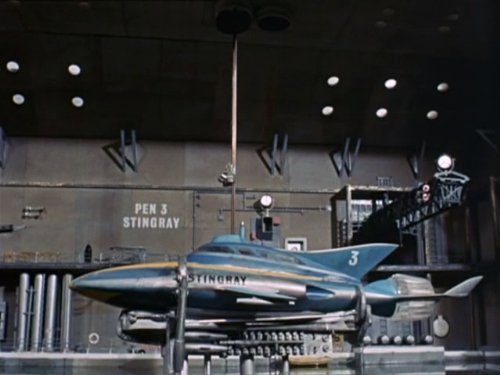

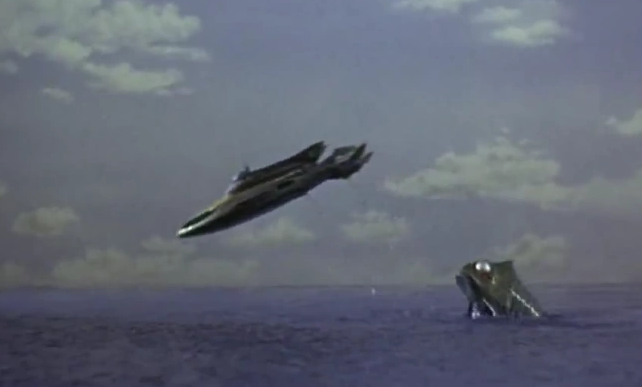

![[June 22, 1965] Standby for Action! (Gerry Anderson’s <i>Stingray</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/650622stingray_title-640x372.jpg)

![[April 26, 1965] A Stranger in a Strange Land (The Stranger, Australian TV SF)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/The-Stranger-8a-672x372.png)

![[April 6, 1965] The Early Bird Catches the Worm (INTELSAT 1)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Intelsat-1-1-620x372.jpg)

![[March 24, 1965] New Leaps Forward in Space (Voskhod 2, Europa F-3, Ranger 9, and Gemini 3)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Voskhod-spacewalk-397x372.jpg)

![[January 20, 1965] The T.A.R.D.I.S. Lands Down Under and Japan Invades Australia (<i>Doctor Who</i> and <i>The Samurai</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/DW-and-Susan-564x372.jpg)

![[January 8, 1965] The Skylark of Space (Britain's Skylark Sounding Rocket)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Skylark-with-Cuckoo-672x372.jpg)