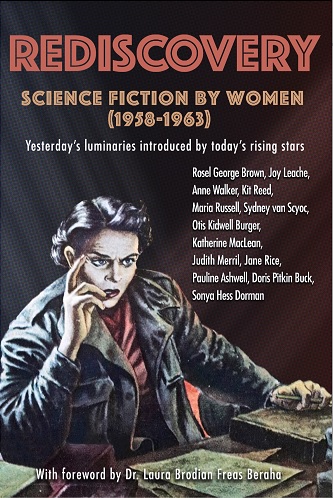

[We have exciting news! Journey Press, the publishing company founded by the team behind Galactic Journey, has just launched its first book. We know you will enjoy Rediscovery: Science Fiction by Women (1958-1963), a curated set of fourteen excellent stories introduced by the rising stars of 2019.

If you enjoy Galactic Journey, you'll want to purchase a copy today — available physically and virtually!]

by John Boston

Georgia on My Mind

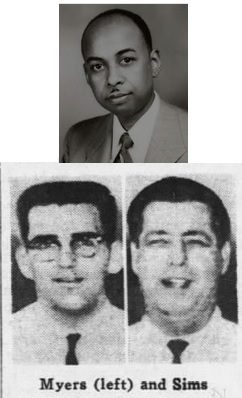

We’ve just seen that standing up for civil rights in the South is a hazardous business from the murder of the civil rights workers Goodman, Chaney, and Schwerner. It looks like merely being a Negro passing through the South can be just as hazardous, even in the service of one’s country.

Lemuel Penn was an assistant superintendent in the Washington, D.C., school system, a decorated veteran of World War II, and a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army Reserve. There’s an annual summer training camp for reservists, and Colonel Penn went to Fort Benning, Georgia, for the occasion. Driving back to Washington on July 11, Colonel Penn and two fellow reservists were noticed by members of the Ku Klux Klan, who followed them and killed Penn with two shotgun blasts.

The Klansmen were easily identified and brought to trial remarkably quickly—and acquitted last week by an all-white Georgia jury, according to the local custom.

But the last word may remain to be spoken. Days before the murder, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which authorizes prosecution of such civil rights violations in federal court by federal authorities, was enacted. Will it make a difference, before another Southern jury? And will the federal government reconsider a practice that requires Negroes to travel to the South where their mere presence may provoke local racist whites to homicide?

The Issue at Hand

The October 1964 Amazing is fronted by an Ed Emshwiller cover that is, if anything, more hideous than the one on the July issue, though more capably rendered. It looks like something a non-SF artist might do satirically for a mainstream magazine article trashing SF as silly and juvenile; more charitably, like a failed attempt at an Ace Double cover that Emshwiller found in the back of his closet. I wonder if it was meant for one of A.E. van Vogt’s Null-A books. The guy in the shiny white flying chair (notice how much it looks like he’s sitting on a toilet?) has a forehead high enough to accommodate an extra brain, or two or three. The contrast between this and Emshwiller's much more sophisticated work for Fantasy and Science Fiction (for example, the April 1964 issue) is nothing short of . . . amazing.

Enigma From Tantalus (Part 1 of 2), by John Brunner

by Ed Emshwiller

by Ed Emshwiller

The cover story is John Brunner’s Enigma from Tantalus, a two-part serial beginning in this issue, which per my practice I will read and review when it is complete. Of course its mere presence is a source of trepidation. Which Brunner are we getting? The Brunner of the capable and intelligent novelets and novellas he has been publishing for years in the British SF magazines, some of which have been fixed up into fine books such as The Whole Man and Times Without Number? Or the pretentiously befuddled Brunner of his last appearance here, February’s The Bridge to Azrael? Stay tuned. Stars, hold back your radiance.

In the Shadow of the Worm, by Neal Barrett, Jr.

Once past the serial, the major fiction item is In the Shadow of the Worm, a long novelet by the unevenly talented Neal Barrett, Jr. The blurb telegraphs this one: “The Beautiful Lady . . . the Android who does but may not love her . . . the Mad Villain . . . the Unutterable Menace . . . These are stock (almost laughing-stock) figures of science fiction. Now Neal Barrett . . . takes them and makes them vibrant with suspense, with poetry, with meaning.”

Uh-oh.

Well, the bad news is that the story is in large part an exercise in bombastic oratory and striking of poses. The mitigating news is that Barrett sort of brings it off, at least in its own terms. The Lady Larrehne (am I the only one tired of a human future festooned with titles of nobility?), with her non-man Steifen, an artificial person programmed to serve and obey her, have crossed space in the good ship Gryphon (“Oh, fearsome and great she is! A league and a half of terror and love from silver beak to spiked bronze tail—a’shimmer with golden scales from steel-ruffle neck to dragon wings; and each bright horny shield as wide as fifty humans high.”).

They are now on Balimann’s Moon, presided over by the Balimann (sic), which orbits around a planet called Slaughterhouse, which apparently produces meat for the rest of the galaxy, in the form of parodic engineered animals without much to them except the edible (“terrible blind herds stumbling toward death before birth could register on feeble brains”). Slaughterhouse in turn is ruled by one Garahnell, who ostentatiously stages phony space battles for the visitors.

But why are Larrehne and Steifen here anyway? To see the Worm, a/k/a the Eater of Worlds, an entity, force, effigy, or something between our galaxy and Andromeda and heading our way, and Balimann’s Moon is the best vantage point (“the last sprinkled mote of sand before the great sea begins”).

They are also here to visit Slaughterhouse, though somehow that goal gets lost in the proceedings. Everything is symbolic, of course, as the characters point out in case you missed it. Says the Lady: “Is there a more cutting parody of the Good and Evil we have known back there, than Garahnell’s mock war—or the birth-death of Slaughterhouse? When I think of the life we left—Oh, Steifen, it’s hard to say which nightmare mirrors the other!”

There’s more, much more, including but not limited to the fate of humanity, all saved from terminal tiresomeness by Barrett’s sure touch with his contrived and gaudy style. This is not at all my cup of tea, but I must concede it’s well brewed. Three stars.

Urned Reprieve, by Arthur Porges

by Robert Adragna

Next is the trivial and annoying Urned Reprieve by Arthur Porges, another contrived little story of Ensign Ruyter triumphing over adversity with very basic science. Ruyter is about to be sacrificed by primitive aliens to their jealous god but saves himself with a demonstration of air pressure that wows the savages. This is dreary enough to start, but Porges notes in passing that these aliens “were quite primitive, roughly on the level, it would seem, of the Red Indian tribes of Earth’s infancy.” Doesn’t this guy know anything besides junior high school science? Maybe he should start with Edmund Wilson’s Apologies to the Iroquois (1960), about some “Red Indians” who were arguably more civilized than the people who subjugated them. Two stars, grudgingly.

The Intruders, by Robert Rohrer

by Blair

The suddenly prolific Robert Rohrer is here, for the third consecutive issue, with The Intruders, an improvement over its predecessors. It’s a jolly romp about a maniac with a meat cleaver trying to avoid and defeat his pursuers, from the maniac’s point of view, set in a spaceship rather than a haunted house (and being in the spaceship is what drove him mad—that’s what makes it science fiction and not just an updated rehash of Poe). (That’s mostly a joke. Sort of.) The hackneyed extremity of the plot is made tolerable and quite readable by an economical style that focuses on mundane physical detail and agreeably contrasts with its loony content. This Rohrer is getting pretty good; if he sticks with it he may produce something memorable. Three stars, towards the high end.

Demigod, by R. Bretnor

by Virgil Finlay

The last piece of fiction here is Demigod, by R(eginald) Bretnor, who has not previously appeared in Amazing, being most frequently found in Fantasy & Science Fiction, with the occasional foray into Harper’s, Esquire, Today’s Woman, and the like. The Demigod is a giant golden-green humanoid who emerges from his spaceship at “the isle and port of Porquegnan, where Lucullus Sackbutt’s yacht, the Grand Eunuch, swam at anchor in an emerald sea and an atmosphere delicate with hints of duck and truffle and whispered music.”

We are quickly introduced, inter alia, to Mr. Sackbutt, the Mayor Hippolyte Ronchi, “a large, middleaged woman named, of all things, Mme. Bovary, who had come to deliver Lucullus Sackbutt’s more intimate and finer laundry,” Sackbutt’s “little friend,” Prince Alexei Alexandrovitch Tsetsedzedze, “known familiarly as Poupou . . . but who had nonetheless found his way to Lucullus Sackbutt via dress-designing and interior decorating.” Sackbutt has only just come from his bath, with “a pair of lithe, young, naked Nubian girls, whose duty it was to wash him, and who had long since learned that nothing at all exciting was going to happen to them while at work,” while Prince Poupou read to Sackbutt from his projected biography of Sackbutt, patron of the fine arts and arbiter of taste.

So Sackbutt appears to be a stereotyped homosexual, and the story continues in its arch and mannered fashion to parody what was undoubtedly a parody to begin with. The Demigod approaches Sackbutt and stares at him, from which Sackbutt infers that he has been selected to parade for this first alien visitor all the achievements of Earthly high culture, while the rest of the world looks on, until the Demigod decides he has had enough and carries Sackbutt off to a summary end. Bretnor is adept enough at this artificial style (reminiscent of an overstimulated P.G. Wodehouse) to keep it amusingly readable enough, as long as one can ignore the fact that the whole thing is an exercise in exploiting the last prejudice that seems to be acceptable everywhere. Two stars for execution discounted for silliness, a burnt-out cinder for moral stature.

Jack Williamson: Four-Way Pioneer, by Sam Moskowitz

An almost welcome note of the prosaic is sounded by Sam Moskowitz, with his SF Profile, Jack Williamson: Four-Way Pioneer. This one begins by quoting a New York Times review stating that Williamson’s writing is “only slightly above that of comic strip adventure”—a review which netted Williamson a job writing a comic strip, Beyond Mars in the New York Daily News Sunday edition. This may not be the credential Mr. Williamson would most like to see heralded.

Aside from this promotion by pratfall, Moskowitz recounts Williamson’s childhood in the wilds, or at least the farmlands, of Mexico and the Arizona Territory, his discovery of this very magazine in 1927, his success at selling A. Merritt pastiches to it starting in 1928, and his development as a more versatile writer in the 1930s. Moskowitz describes Williamson’s 1939 novella The Crucible of Power as “a giant step towards believability in science fiction” (read it and draw your own conclusions). As usual, Moskowitz focuses on Williamson’s material of the ‘20s and ‘30s, with less emphasis on the ‘40s and none at all on his post-1950 work (two novels on his own not worked up from earlier writings, plus one in collaboration with James Gunn and four in collaboration with Frederik Pohl, and a dozen-plus short stories); his sole comment is “But science fiction stories continue to trickle out.”

Oh, the four ways? “He is an author who pioneered superior characterization in a field almost barren of it; new realism in the presentation of human motivation; scientific rationalization of supernatural concepts; and exploitation of the untapped story potentials of anti-matter.” You might think becoming an academic with a specialty in science fiction was one, too. Anyway, three stars; this one is a little meatier than Moskowitz’s usual.

Summing Up

Who would have thought it? An issue of Amazing in which the merit, such as it is, of most of the fiction contents turns on the authors’ mastery of style: in Barrett’s and Bretnor’s cases, their ability to maintain a grossly artificial style consistently enough to keep the reader going, as opposed to laughing at their lapses, and in Rohrer’s, his ability to recount bizarre and grotesque events in the plainest and most matter-of-fact language so the story will not seem as far around the bend as its protagonist. Well, you take what you can get with this hit-or-miss magazine.

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

![[September 12, 1964] A Mysterious Affair of Style (October 1964 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/amz1064cover-618x372.png)

![[August 15, 1964] What are you thinking? (<i>The Whole Man</i> aka <i>Telepathist</i> by John Brunner; <i>The Universe Against Her</i>, by James H. Schmitz)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/640815covers-672x372.jpg)

![[May 2, 1964] The Big Time (May 1964 <i>Analog</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/640502cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 12, 1964] SINKING OUT OF SIGHT (the February 1964 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/640112cover-672x372.jpg)

![[January 2, 1964] All's well that ends well (January 1964 <i>Analog</i> science fiction)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/640102cover-653x372.jpg)

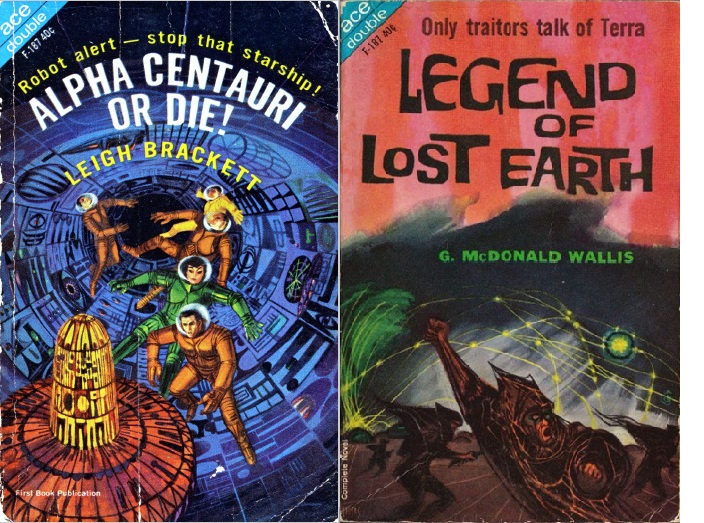

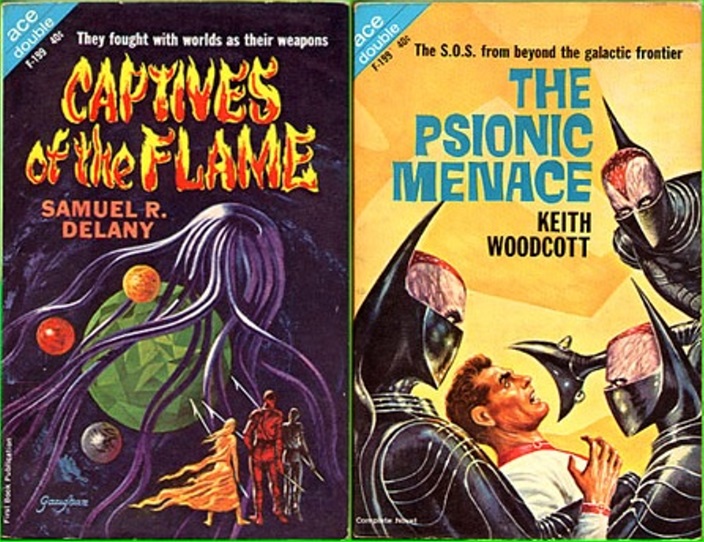

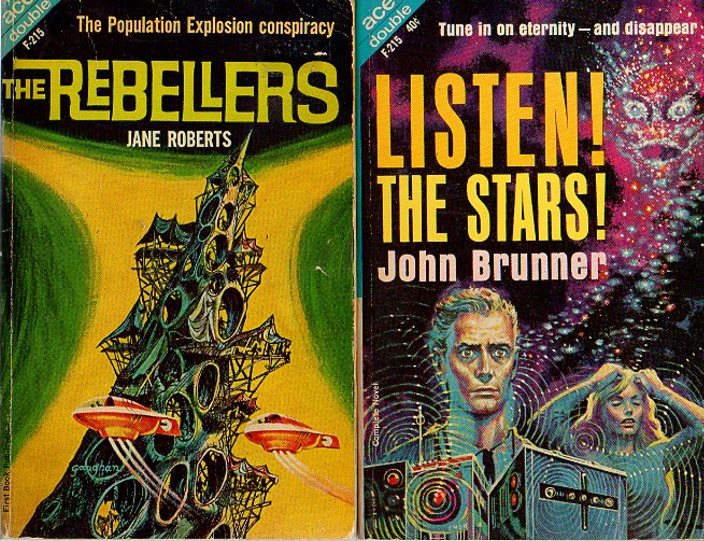

![[November 17, 1963] Galactoscope (Three Ace Doubles!)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/631117f187-672x372.jpg)

![[October 8, 1963] The Big Lemon (November 1963 <i>IF</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/631008cover-474x372.jpg)

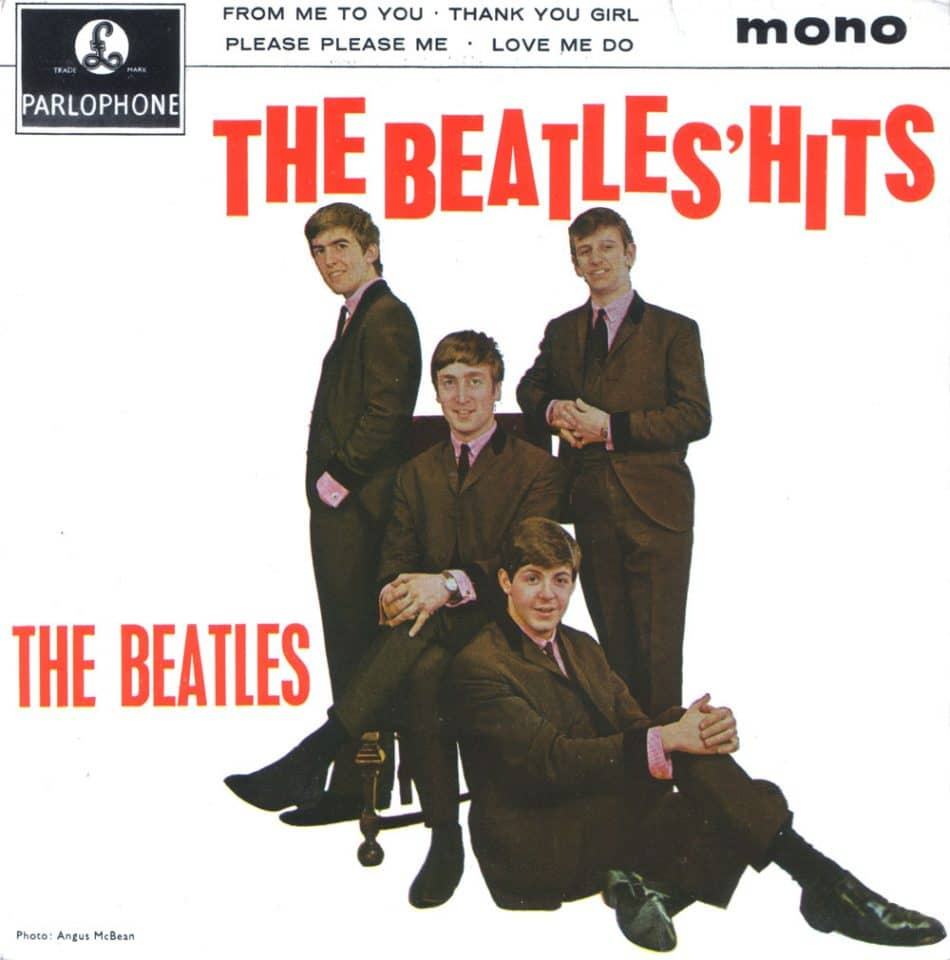

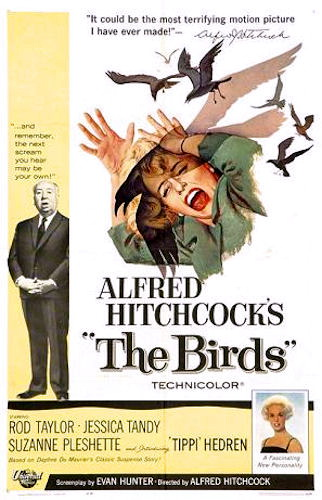

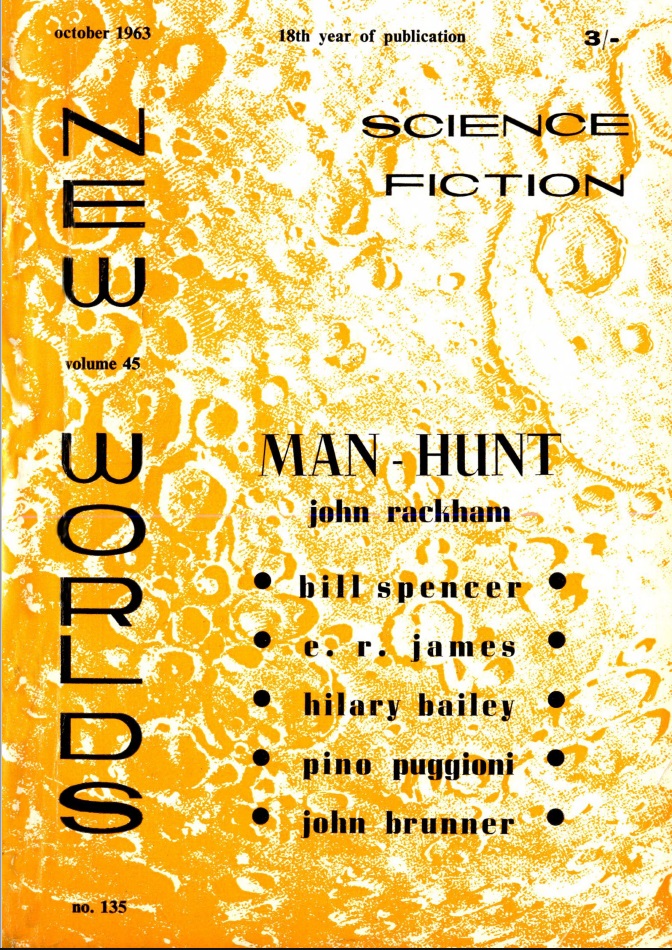

![[September 27, 1963] Beatles, Birds and Brunner (<i>New Worlds</i>, October 1963)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/630927cover-672x372.jpg)

![[August 27, 1963] Ups and Downs #2 <i>New Worlds, September 1963</i>](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/630827cover-409x372.jpg)