[If you live in Southern California, you can see the Journey LIVE at Mysterious Galaxy Bookstore in San Diego, 2 p.m. on February 17!]

by John Boston

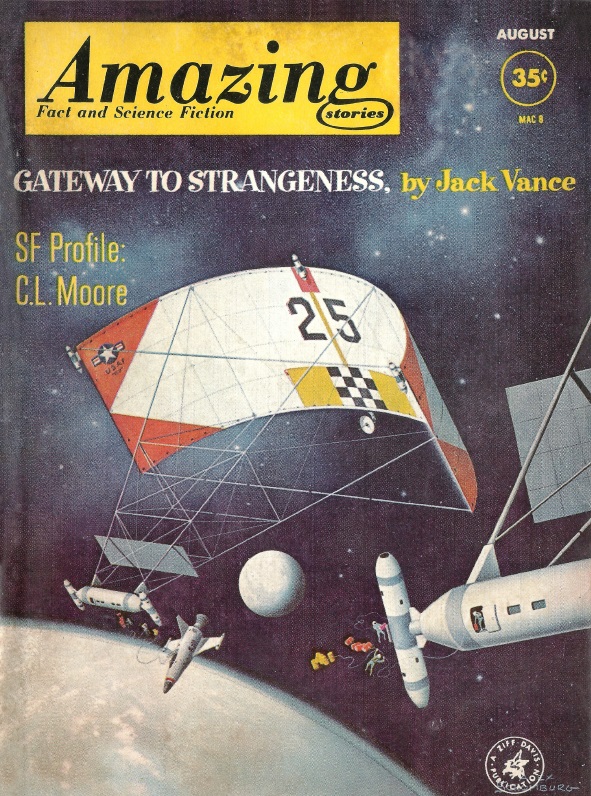

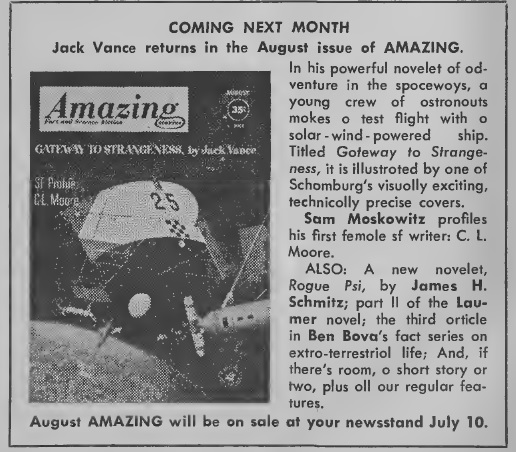

Well, hope springs eternal, and a good thing for certain SF magazines that it does. The March Amazing has a rather distinguished table of contents: a novelet by John Wyndham and short stories by veterans Edmond Hamilton, H.B. Fyfe, and Robert F. Young and up-and-comers like J.G. Ballard, rising star Roger Zelazny, and variable star Keith Laumer.

But we must temper optimism with realism: since Amazing is about the lowest-paying of the SF magazines, top-market names are probably here with things they couldn’t sell elsewhere. So, prepared for all eventualities . . .

Edmond Hamilton’s Babylon in the Sky is a simple morality tale for SF fans. Young Hobie lives in the sticks, where there are no jobs and people survive on doles and make-work, seldom make it past the eighth grade, and resent eggheads and know-it-alls—especially the decadent ones in the orbiting cities that Hobie’s preacher father rails against. So Hobie runs away to the spaceport and stows away to one of these satellites, planning to sabotage the power plant and blow it up. He doesn’t get far, and the sane and reasonable people there explain to him that they are not living sybaritic lives but working hard at research to benefit everyone. We didn’t rob you, Hobie, the home folks did. So they’re just sending him back, but Hobie, you’re a smart kid, if you go to the Educational Foundation near the spaceport, they’ll take care of you, and then maybe you can join up and come back here. Hobie buys it. Well, yeah, that’s more or less my life plan too if I can swing it, but I don’t read SF for homilies even if I agree with them. It’s slickly enough done, but two stars for unearned propagandizing.

Speaking of slick, here’s Robert F. Young again. When last he appeared, I said he “knows so many ways of being entirely too cute,” and boy howdy was I right. In Jupiter Found, the protagonist’s brain, after an auto accident did for the rest of him, is installed in a giant mining and construction machine on Jupiter—a M.A.N. (Mining, Adapting Neo-Processor), model 8M. He is shortly joined by model EV, who is of course a W.O.M.A.N. (Weld Operating, Mining, Adapting Neo-Processor). They work for Gorman and Oder Developments, which has strictly forbidden them to process an ore called edenite, and they’ve also been warned to beware of a guy who has been cast out of a high place in the company and is now in business for himself, who will be sending down a mining unit called a Boa 9. By this point in Young’s arch and labored rendition of the Old Testament I was thinking longingly of some of the more bloodthirsty passages in Leviticus. One star. What kind of rubes does this guy think he’s writing for? Even Hobie wouldn’t go for this.

John Wyndham is best known for his chilly novels of the 1950s, from The Day of the Triffids to The Midwich Cuckoos, less so for Trouble with Lichen (1960), intelligent and readable but much less incisive than its predecessors. His novelet Chocky is unfortunately in the latter vein. The protagonist’s kid seems to be having conversations with an imaginary friend, except anybody who’s read a lick of SF will know immediately that he’s communicating with an extraterrestrial intelligence. So we get the worried parent routine, and the marital tension, and the visit from the child psychologist friend, the rather subdued climax, and then . . . some explanation and it all goes away. The whole 38 pages worth is so low-key as to be near-comatose. One wonders if Wyndham is taking some of the new tranquilizers that psychiatrists hand out these days. It’s benignly readable but there’s not much to it. Two stars.

Roger Zelazny’s short The Borgia Hand is livelier but insubstantial, about a young man with a withered hand in generic fairy-tale country who chases down a pedlar (sic) reputed to traffic in body parts. Yeah, he’s got a hand in stock, and here’s a quick gimmick and it’s over. Two stars. Snappy writing is nice, but as one noted critic put it, where’s the bloody horse?

But relief is in sight. There’s nothing especially original about Keith Laumer’s The Walls: future overpopulated Earth with people living regimented lives stuffed into tiny spaces in big apartment complexes; protagonist’s husband is on the make and brings home a Wall, i.e. a TV screen that covers one wall. You can turn it off but then you’ve got a wall-sized mirror. Next, another Wall; then another; then . . . . The story is the wife’s psychological disintegration stuck all day with a choice of all-directions TV-land or a hall of mirrors, but—as with It Could Be Anything from a couple of issues ago—Laumer’s knack for concrete visual detail brings it off and keeps it from being a print version of one of those lame Twilight Zone episodes which end with somebody going crazy. Four stars.

J.G. Ballard is back with The Sherrington Theory, his most minor effort yet in the US magazines. Protagonist and wife are at a beach cafeteria terrace, watching the remarkably dense beach crowd (no sand visible), and intermittently discussing the theory of Dr. Sherrington that the imminent launch of a new communications satellite will trigger certain “innate releasing mechanisms” in humans, which of course it does. This one frankly reads a bit like a self-parody; in fact, the idea is a sort of domesticated knock-off of the one he developed much more effectively in The Drowned World. Of course it’s written with Ballard’s usual flair (or mannerisms, as you prefer), e.g.: “. . . this mass of articulated albino flesh sprawled on the beach resembled the diseased anatomical fantasy of a surrealist painter.” The situation is more skillfully developed and built up than in Zelazny’s story, bringing it up, barely, to three stars.

The stars hide their faces as we come to H.B. Fyfe’s Star Chamber, a shameless Bat Durston in which a parody of a despicable criminal has crash-landed on an uninhabited planet and a lone lawman has come after him. It reads like something Fyfe couldn’t sell to Planet Stories until the mildly clever end, which reads like something he couldn’t sell to Analog because they were overstocked on Christopher Anvil. Two stars, barely.

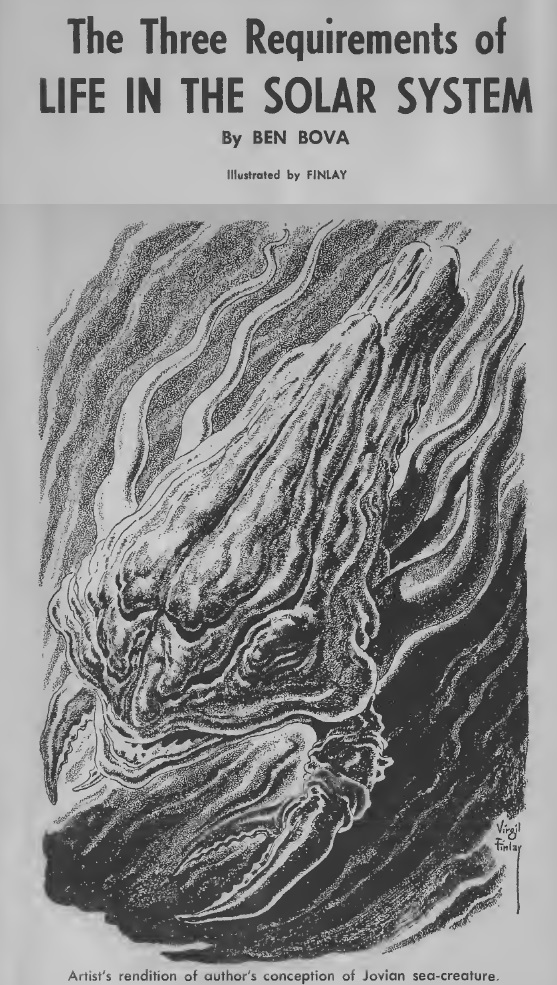

And here is earnest Ben Bova with Intelligent Life in Space. Haven’t we seen this already? Not quite—this time he’s going on about the definition of intelligence, touching base at ants, dolphins, and chimpanzees, and suggesting that we’re not likely to find it in the Solar System but likely will do so farther away. This one is a more pedestrian rehash of familiar material than most of his earlier articles. Two stars.

So: one very good story, one amusing one, and downhill—pretty far downhill—from there. Hope may spring eternal, but one takes what one can get.

[P.S. If you registered for WorldCon this year, please consider nominating Galactic Journey for the "Best Fanzine" Hugo. Your ballot should have arrived by now…]