by John Boston

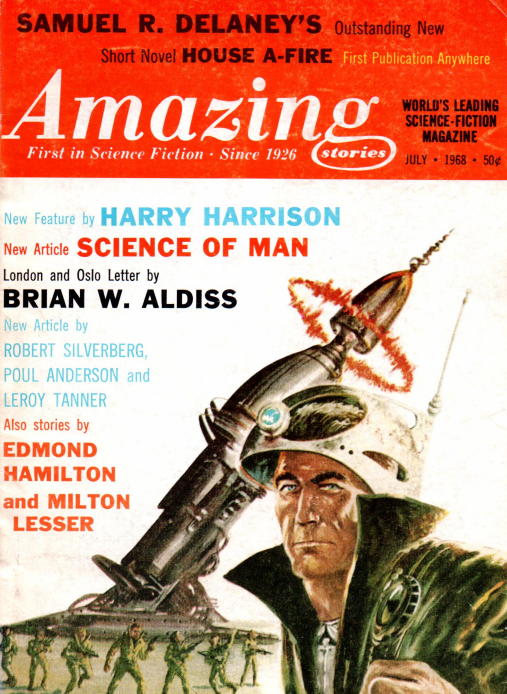

In this January's Amazing, on page 138, there is an editorial—A Word from the Editor, it says, bylined Barry N. Malzberg—which suggests a different direction (or maybe I should just say “a direction”) for this magazine. First is some news. There will be no letter column; Malzberg would rather use the space for a story. Second, “the reprint policy of these magazines will continue for the foreseeable future,” per the publisher, but “A large and increasing percentage of space however will be used for new stories.”

by Johnny Bruck

Pointedly, the editor adds, “it is my contention that the majority of modern magazine science-fiction is ill-written, ill-characterized, ill-conceived and so excruciatingly dull as to make me question the ability of the writers to stay awake during its composition, much less the readers during its absorption. Tied to an older tradition and nailed down stylistically to the worst hack cliches of three decades past, science-fiction has only within the past five or six years begun to emerge from its category trap only because certain intelligent and dedicated people have had the courage to wreck it so that it could crawl free. . . . I propose that within its editorial limits and budget, Amazing and Fantastic will do what they can to assist this rebirth—one would rather call it transmutation—of the category and we will try to be hospitable to a kind of story which is still having difficulty finding publication in this country.”

Sounds good to me! This brave manifesto is only slightly undermined by the familiar production chaos of the magazine. It is not acknowledged on the table of contents, and does not appear in the usual place for an editorial, at the beginning of the magazine. Instead, there appears a piece labelled Editorial by Robert Silverberg, S-F and Escape Literature, which (though touted as “NEW” on the cover) actually dates from six years ago, when it appeared as a guest editorial in the August 1962 issue of the British New Worlds. Silverberg is also listed as Associate Editor.

Silverberg’s piece briskly disposes of the “escapist” critique of SF, pointing out that all literature is escape literature; it’s just a matter of where you’re escaping, and how well the escape is executed. “The human organism, if it is to grow and prosper, needs change, refreshment, periodic escape.”

The other non-fiction in the issue includes another Leon Stover “Science of Man” article (see below). There is the by-now-usual book review column, attributed to James Blish on the contents page, with reviews by his pseudonym William Atheling, Jr. (mixed feelings about Clarke’s 2001 novelization, praise for D.G. Compton and Alexei Panshin); by Panshin (praise for R.A. Lafferty); and by editor Malzberg (praise for the new edition of Damon Knight’s In Search of Wonder, mixed feelings about Alva Rogers’s fan tribute A Requiem for Astounding). There is also a movie review, by Lawrence Janifer, of Rosemary’s Baby; he finds it well done but dull, and—in an unexpected juxtaposition—quotes Virginia Woolf: “But how if life should refuse to reside there?”

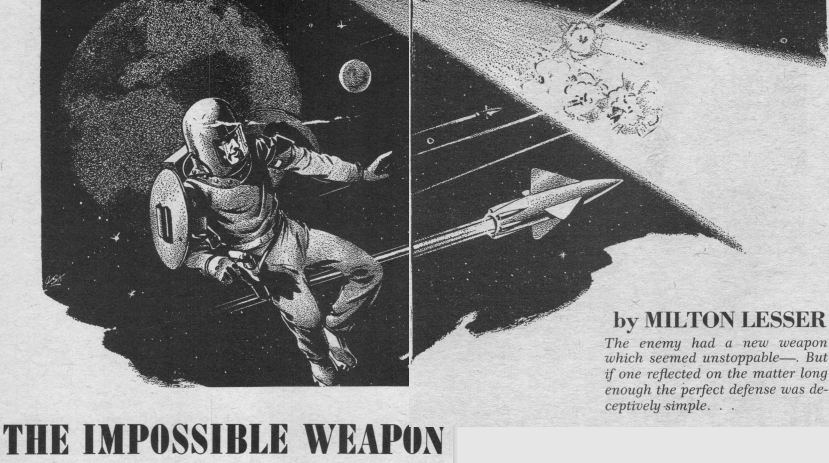

We All Died at Breakaway Station, by Richard C. Meredith

by Dan Adkins

The major piece of new fiction is Richard C. Meredith’s We All Died at Breakaway Station, first part of a two-part serial. As usual I will read and review it when it’s complete; a quick rummage reveals it’s a space war story whose plot would probably have been right at home in Planet Stories, but which looks much grimmer than the pulps allowed.

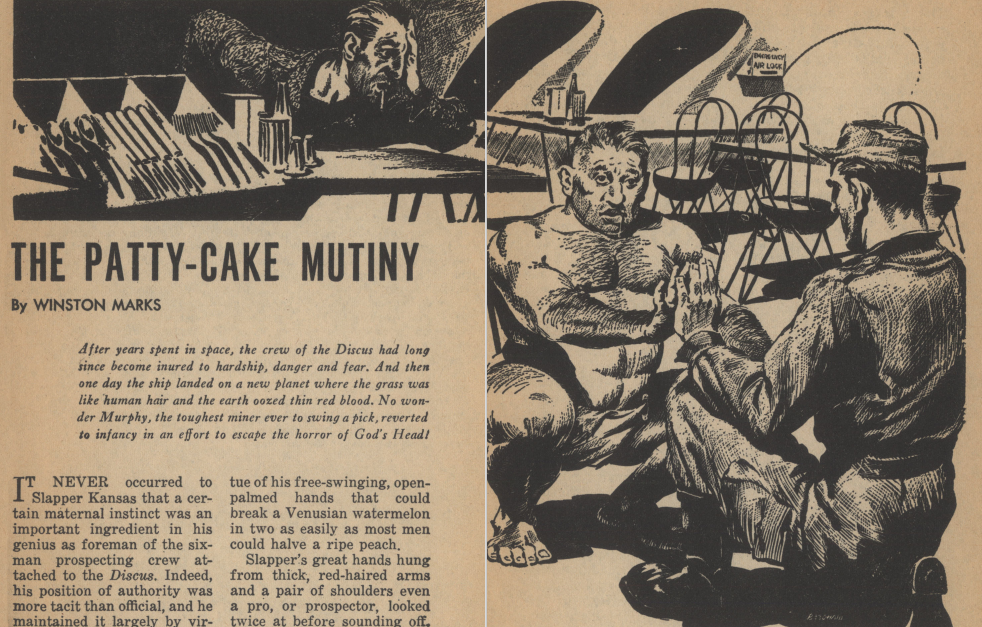

Temple of Sorrow, by Dean R. Koontz

Dean R. Koontz’s novelet Temple of Sorrow is a breezily parodic procession of stock genre elements—the protagonist with a mission (“My name is Mandarin. Felix Mandarin.”—from “International,” we later learn), accompanied by Theseus, his Mutie bodyguard (actually a bear, “developed” in the Artificial Wombs), to pierce the veil of a powerful religious cult (with overtones of the one in Heinlein’s “—If This Goes On,” such as the omnipresence of Naked Angels, female of course). In this post-nuclear war world, the Temple of the Form predicts the Second Coming of the Form (the mushroom cloud), and it seems is bent on bringing it about by stealing the world’s last atom bomb.

by Jeff Jones

Felix is caught and reduced to near-mindless servitude, but his conditioning is broken by his realization of the Bishop’s sadistic plans for the Angel who has caught Felix’s fancy. Rejoined by Theseus, who had fled to the wilderness but returned just in time, Felix and the Angel Jacinda fight their way to the Temple’s Innermost Ring (cameo appearance by a giant spider along the way). And there’s super-science! Felix figures out that the Innermost Rings of all the many Temples worldwide are interdimensionally connected, so if the Temple bigs can set off a bomb in one Ring, the explosion will be replicated in all the others! Conservation of energy be damned.

So they hasten from Ring to Ring, find the bomb, and disarm it. “Any child could disarm an A-bomb if he has read his history and had an instructor in P.O.D. who allowed him to practice live on dummies.” Felix proposes to the Angel Jacinda. Theseus has somehow gained human intelligence during the interdimensional trek. Exit, wisecracking. Or, as the editor put it: “Tied to an older tradition and nailed down stylistically to the worst hack cliches of three decades past . . . .” Good sarcastic fun. Three stars.

How It Ended, by David R. Bunch

And here is the writer half the readership has long seemed to hate, in his second consecutive issue—David R. Bunch. Editor Malzberg says, “I think that Bunch is one of the twenty or thirty best writers of the short-story in English.” I might pick a slightly higher number, but I’m happy he is again welcome here. But this one is called How It Ended—“it” being Moderan, scene of a procession of stories about the Strongholders, their new-metal enhancements held together by the flesh-strips that are all that remain of their human bodies, fighting their endless wars in splendid isolation from each other. Can it really be the end? Time will tell whether Bunch can resist returning to the scene.

But to the matter at hand: during the Summer Truces following the Spring Wars, someone looses a wump-bomb, which is strong stuff indeed. This sets off a new war which is only ended when the narrator releases the GRANDY WUMP (sic), which puts an end to Moderan entirely. This is his confession, rendered onto a tape which may or may not ever be listened to, complete with his litany of self-justification. The inexorable logic leading to complete destruction may be familiar to those who frequent newspapers and government briefing papers. It’s Bunch as usual and you either like it or you don’t. I mostly do, with qualifications, but this one goes on a little too long for my taste. Three stars.

Confidence Trick, by John Wyndham

by Henry Sharp

Moving to the reprints, John Wyndham is here with Confidence Trick (from Fantastic, July-August 1953), about some people going home on a commuter train who discover that it is the train to Hell. They escape their fate only through the loudly expressed disbelief of one abrasive young man, after which the whole illusion falls apart. It is suggested that social institutions such as the banking system are not too different from religions in their reliance on unquestioning faith. It’s smoothly written but becomes a bit heavy-handedly didactic after its comic beginning. Two stars.

Dream of Victory, by Algis Budrys

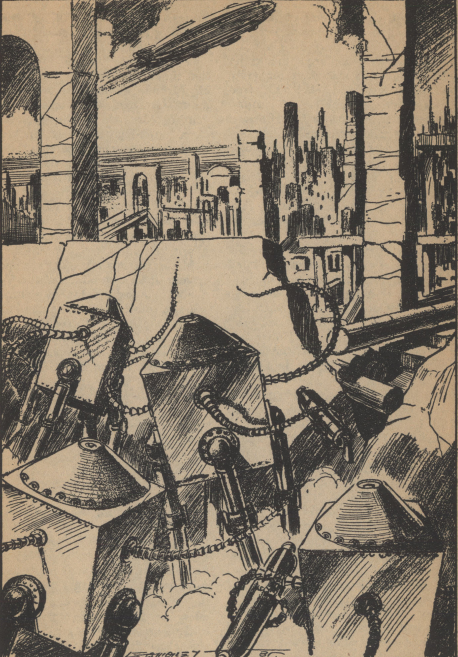

In Algis Budrys’s Dream of Victory (Amazing, August/September 1953)—a “complete short novel” at 26 large-print pages—a war has left the world devastated and depopulated. Androids were developed to provide a work force. They are apparently human in all respects except for standardization of features (which they can pay to have fixed), and they can’t reproduce. Fuoss, an android, is not happy about this, or about the fact that there seems to be growing discrimination against androids; he can get jobs but somehow always loses them, and his successful android lawyer friend tells him the creation of androids has now stopped.

by Ed Emshwiller

Fuoss has a recurring dream about a woman bearing his child. He finds his situation so frustrating that he acts in progressively more self-destructive ways, driving away his android wife, in part because he flaunts his affair with a human woman. Then he loses his latest job, drinks a lot, and his girlfriend throws him out. When he comes back and finds out she has taken up with somebody else, he smashes a whiskey bottle and cuts her throat after she dismisses his delusional babble that she will have his child. His lawyer friend (ex-friend by now) visits him in jail and chastises him for the harm he has done to the android cause. “ ‘Is she dead?’ he asked hopefully.”

I’m not sure what to make of this story. Budrys has commented on it in the introduction to his second collection, Budrys’ [sic] Inferno (UK edition retitled The Furious Future): “Dream of Victory is the first novelette I ever wrote. . . . Dream of Victory, as I was writing it, seemed a free-wheeling piece of technical bedazzlement. Happily, most of the experimentation in it was elevated to more comprehensible levels by Howard Browne, the quietly competent editor who bought it and with his pencil made me look a little more mature than I really was. There is a certain temporary value to a young writer in coming on as a prose innovator and pyrotechnician; I think there is more for the reader and, in the course of time, more for the writer in letting the story speak for itself.”

So, all procedure and no substance about this story in which the protagonist responds to his emotional travail by murdering his girlfriend. I wonder if it is supposed to be a displaced commentary on race relations, especially since the plot seems to bear some similarity to that of Richard Wright’s Native Son (a book I haven’t read and know only second-hand). Did Budrys have it in mind? Probably not. Probably this is just another example of a writer who can’t think of a more imaginative way to resolve the situation of unbearable frustration he has created than with hideous violence against women—not altogether unrealistically, I have to acknowledge, since I do read the newspapers.

It’s tempting to say “nice try,” but it really isn’t; the best thing to say is that Budrys got better later, at least a lot of the time, in finding better resolutions (or accepting no resolution) for the intolerable situations he was so good at coming up with. One star for substance, three for execution (though as Budrys says, much credit goes to editor Browne for that). Split the difference.

Don't Come to Mars, by Henry Hasse

by Leo Morey

Henry Hasse’s Don’t Come to Mars (Fantastic Adventures, April 1950) is a large comedown from his goofily grandiose classic He Who Shrank, reprinted in the last issue. Dr. Rahm awakes to see himself walking out the door, and looks down to see he has a whole new tentacled body. Aiiko the Martian has borrowed his by long-distance projection. Turns out Aiiko is trying to sabotage Dr. Rahm’s life work developing space travel to Mars so humans will avoid the terrible fate that has befallen the Martians. It’s routinely executed and reads more like a story from the ‘30s than one from 1950. Two stars.

Science of Man: Lies and the Evolution of Language, by Leon E. Stover

Leon E. Stover’s “Science of Man” article is Lies and the Evolution of Language, which displays Stover’s faults even more prominently than his earlier articles. The subject is certainly interesting, but the article is mostly a turgid mass of assertions with very little attempt to convince the reader to believe them or to provide any basis to assess them. This is less of a problem when he is addressing current or recent times, of which most readers will have some direct knowledge or experience. But consider: “Without a doubt the first humans replayed the action of the day around the campfire at night in an unabashed display of ceremonial boasting. And doubtlessly manly valor was an entrance requirement into the hunting team, all the more incentive for a male to boast about what he had seen and done so as to be allowed to become ‘one of the boys.’ ” Certainly plausible, makes sense, but “without a doubt”? Without more support than Stover provides, I’ve got a doubt.

Some of Stover’s assertions are more than doubtful, such as his claim that animals cannot lie. In fact there is considerable deception in the animal world. For example, some birds feign broken wings and walk away from their nests, apparently seeking to distract predators from their eggs or young. Stover might have an argument that that behavior is not linguistic enough to be relevant to the discussion. But he doesn’t make it, or acknowledge the question. Two stars.

Summing Up

So, another mixed-bag issue of Amazing (excluding the serial, to be assessed next time), but one that is promising—a word I must have used a dozen times about this magazine, but this time there's an actual promise about what the new editor plans to do with it. As always, we'll see.

[Come join us at Portal 55, Galactic Journey's real-time lounge! Talk about your favorite SFF, chat with the Traveler and co., relax, sit a spell…]

![[December 4, 1968] Sign Me Up (January 1969 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/amz-0169-cover-355x372.png)

![[October 6, 1968] Snail on the Slope? (November 1968 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/amz-1168-cover.png)

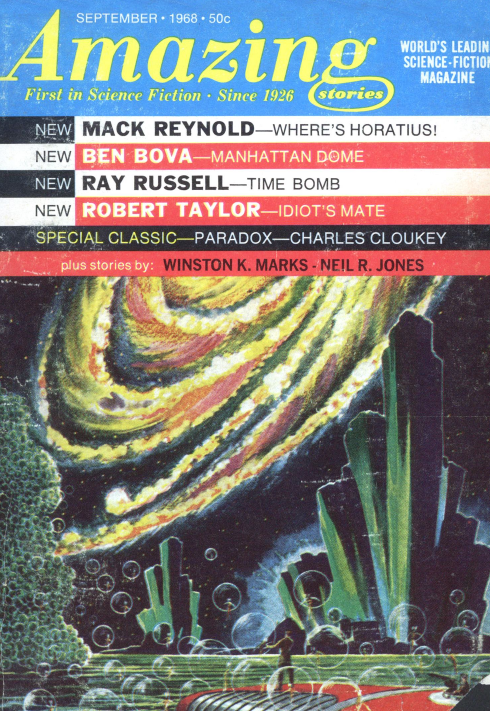

![[August 6, 1968] Treading Water (September 1968 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/amz-0968-cover-490x372.png)

![[July 12, 1968] The Pioneer and the Gorilla: <i>Heinlein in Dimension</i>, by Alexei Panshin](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/heinlein-in-dim-261x372.png)

![[June 6, 1968] The Stalemate Continues (July 1968 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/amz-0768-cover-496x372.png)

![[April 10, 1968] Things Fall Apart (April 1968 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/amz-0468-cover-447x372.png)

![[January 14, 1968] As Is (February 1968 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/amz-0268-cover-492x372.png)

![[November 20, 1967] Fresh Air? (December 1967 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/amz-1267-cover-497x372.png)

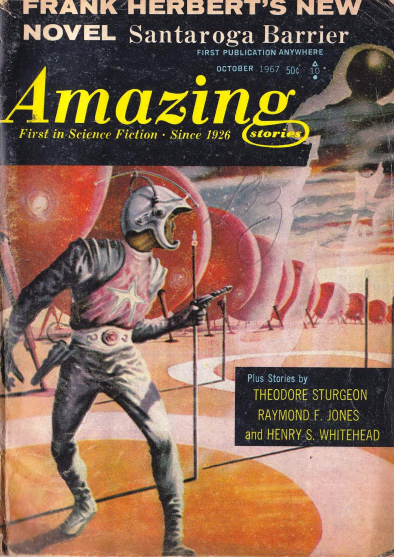

![[September 6, 1967] New Look, New . . . ? (October 1967 <i>Amazing</i>)](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/amz-1067-cover-394x372.png)

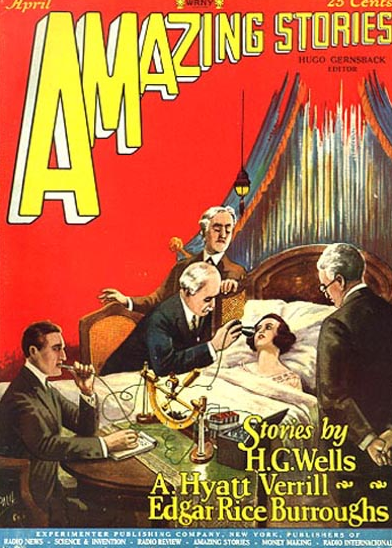

![[August 20, 1967] Hugo Gernsback, 1884-1967](https://galacticjourney.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/gernsback-1929-486x372.png)