The results of the Republican National Convention, held in Chicago this year, are in. They should hardly come as a surprise to anyone: Vice President Richard M. Nixon is the Republican candidate for President of the United States.

I say that this news is unsurprising with good reason–namely, that Nixon essentially ran unopposed. Oh, sure, Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater was putatively in the race, and New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller has been front and center in the headlines over the past two months, but the former never had a chance, and the latter never formally threw his hat into the ring. In fact, it appears that "Rocky's" blistering rhetoric, put forth in print as a set of polemics, was intended to influence the Republican platform rather than propel him into the candidacy. Well, Rockefeller can certainly boast this season–he got Nixon to come to his parlor on bended knee, and much of what Rockefeller espoused made its way into the platform and Nixon's agenda.

In fact, given the rather moderate tone of the GOP platform, voters may have trouble choosing between the two parties' men come November. One thing I noted, comparing Nixon's acceptance speech to Kennedy's, I would give the inspirational and demagogic nod to the latter. While Kennedy poetically described the New Frontier of the 1960s, challenging us all to become its pioneers to make the nation and the world a better place, the main thrust of Nixon's message seems to be, "We're better than the Communists." Well, no one doubts that, but as a wise person once said (this quote is attributed to Ernest Hemmingway, but it predates him), "There is no nobility in being superior to someone else; true nobility comes in being superior to one's former self."

The only real mystery of the convention was Nixon's choice for his running mate. Interestingly, the Republican Vice Presidential candidate is Henry Cabot Lodge, the Massachusetts Senator whom Kennedy defeated in 1952 to begin his career in the upper division of Congress. Now ambassador to the United Nations, and a strong advocate for that body's peacekeeping capabilities, I believe he is a good selection for the No. 2 spot. He will, however, not help Nixon sway the South from the Democratic grasp anymore than Nixon's rather progressive stance on racial issues. I expect this election to be a tight one, fought largely in the relatively liberal areas of the North East, the Great Lakes, and the West Coast.

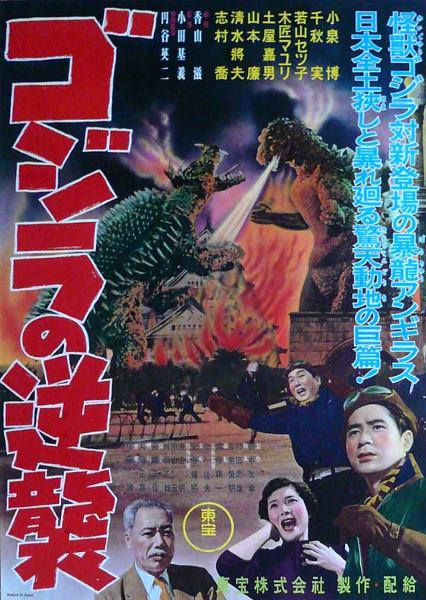

For those who follow my travels, I am currently on the train to the industrial city of Nagoya, a few hours west of Tokyo. Here are some pictures of the Shinjuku area of Japan's capital, which is currently experiencing something of a revitalization in anticipation of the Olympics, time after next. For anyone who was worried for our welfare, there were no signs of unrest, and we have been treated with courtesy, even warmth. We had a great time in Kabukicho and Nihonbashi–in the latter, we supped at an excellent little jazz club where someone had set up a mobile projector and was showing old Felix the Cat cartoons. The best part of travel is the serendipitous pleasures.

In other, Journey-related news, the month of July is over, and it's time to see how the Big Three digests fared, quality-wise. It's a tough choice between Galaxy and F&SF this month. Both clock in at a little over three stars. I think I'll give the nod to the former, for being longer if nothing else. My favorite story this month was probably Stecher's An Elephant for the Prinkip, though none stood out prominently. Only one female writer made an appearance this month: Rosel George Brown.

As for next month, I didn't see any new books of interest, but I will be watching the films Dinosaurus and The Time Machine. Also, expect coverage of a number of exciting, recently announced satellite launches, both military and civilian. I've also just finished the final installment of Anderson's The High Crusade, and it was excellent. I'll have a review for you next time around.

Stay tuned!