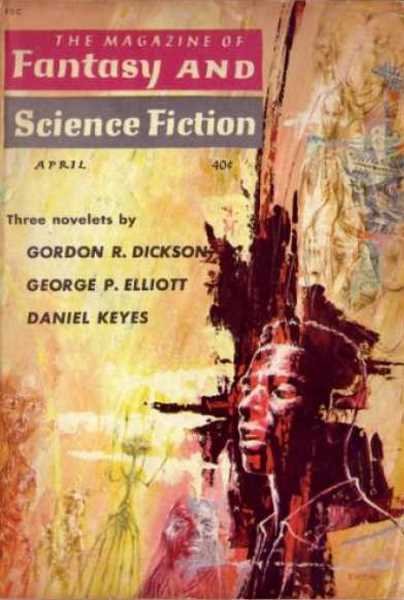

The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction regularly beats out the other regular digests in terms of consistent quality. This month's, April 1960, is no exception.

There's a lot to cover, so let's dive right in:

Daniel Keyes, who wrote the superb Flowers for Algernon, has returned with the issue's lead novelette, Crazy Maro. Our viewpoint character is an attorney who has been contracted by unseen agents from the future to secure psychically adept (and invariably disadvantaged) children for work in a later time. The fellow meets his match, however, when he is asked to recruit the titular Maro, a young black man with an uncanny talent for reading the emotions of others. Much of the novelette is a mystery story, with the lawyer trying to puzzle out the root of Maro's power. It's a powerful piece, assuredly, though the very end is unnecessarily melodramatic.

Another serious piece is The Hairy Thunderer by "Levi Crow" (Manly Wade Wellman in disguise). The writing is deceptively simplistic, describing the arrival of a hairy pale foreigner to the lands of an American Indian tribe. The European commences to ensnare the tribe with his boom stick and, more effectively and terribly, his firewater. A young man of the tribe, Lone Arrow, is able to resist him with the magical assistance of a certain eight-legged class of arthropods.

The moral of the story, that one should be kind to spiders for they are misunderstood but fundamentally good creatures, is one that resonates strongly. I'm always hoping that, when I die, the Spider Gods will look favorably upon me for the compassion and mercy I have shown Their Kind.

G.C. Edmondson's forgettable short story, Ringer features a fellow who is replaced by a robotic doppelganger. The twist is that the viewpoint is always that character, whether in human or android form.

The incomparable Edgar Pangborn brings us The Wrens in Grampa's Bears, in which "Grampa," the narrator's Great Grandfather, hosts a brood of beneficient angels within his long beard. Their existence is only hinted at, and the story is mostly a mood piece capturing the sunset of an old man's life in the Summer of '58, a man whose memories encompass both Gettysburg and satellites. Yet, the theme of the tale is not how much things have changed, but how they stay essentially the same.

A Certain Room, a short by Ken Kusenberg, translated from German by Therese Pol, is a silly, archaic piece. What happens when you fiddle with the objects in a room that have a causal connection to bigger, worldwide events? Not much good.

George Elliott has the issue's second novelette, the fantasy-less, science-fiction-less, but nevertheless compelling Among the Dangs. It is a mock account of an anthropologist's sojourn amongst the fictional Dang tribe of Ecuador. Enlisted for his talent for mimicry and his dark skin, the protagonist spends years living with the Dang, learning their customs and even taking a wife, so that he can become one of their high prophets. His initial motivation is to compose a thesis for an advanced degree. But so complete is his indoctrination that it is only through a titanic force of will that he breaks free, and the experience forever marks him.

The piece originally appeared a couple of years back in Esquire, and it is a strange story to find within the covers of F&SF. On the other hand, while the content is neither science fictional nor fantastic, there is a certain flavor to it that allows it to fit nicely in the middle of this issue. I'm not complaining for its inclusion.

I'm not sure what to do with Rosel George Brown. I really want to like her, but she has this tendency toward first-person pieces featuring scatterbrained housewives. Their situations are tediously conventional and exhaustingly frenetic. I have to wonder if the stories aren't semi-autobiographical. A Little Human Contact continues in this vein, and while it's not horrible, it is still not the masterpiece I know Brown is capable of. Of course, I may be looking in the wrong place–Amazing and Fantastic are still around, and I understand she's due to be published there soon.

Isaac Asimov has an excellent non-fiction piece this month, It's About Time, describing the evolution and fundamental incompatibility of our various calendar systems. The conclusion: trust the astronomers and go with Julian dating.

I won't spoil Joseph Whitehill's In the House, Another since it's a one-trick pony. Cute, though.

Rounding out the issue is Gordy Dickson's latest novelette, The Game of Five. It is strangely reminiscent of his earlier The Man in the Mailbag, but it's not as good. Both stories involve a man infiltrating an alien culture to rescue a captured woman. In both stories, it quickly turns out that the situations are more complex than they seem at first blush. In both stories, the "captured" woman turns out to be an agent of some kind.

But though Five is competently written, the Hercule Poirot moment, that bit at the end where the hero explains the mystery, is not supported strongly enough by clues in the narrative. The world is also not as interesting as the one depicted in Mailbag. Unlike the former title, I don't this one will get nominated for any Hugos. Not that it's bad, mind you—just not up to the bar Dickson has set for himself.

That's it for April 1960. I have a whole new crop of magazines and books to review for next month. I also have far more time to devote to the column now that I am between day jobs. Cry not for me—it was a decision long coming and well worth it.

In the meantime, before we get onto things fictional, I have some scientific news with exciting science fiction ramifications…

…but you'll just have to wait two days for it!

—

(Confused? Click here for an explanation as to what's really going on)

This entry was originally posted at Dreamwidth, where it has comments. Please comment here or there.