by Gideon Marcus

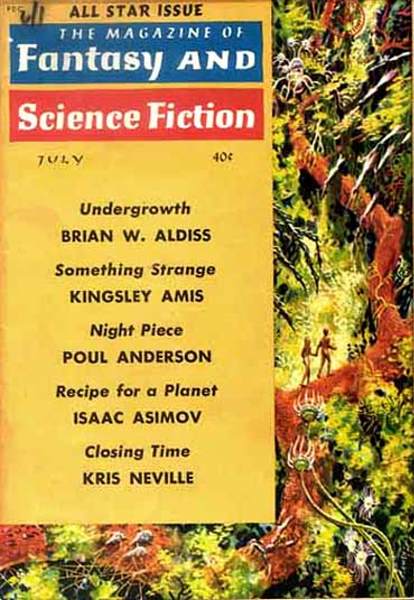

Take a look at the back cover of this month's Fantasy and Science Fiction. There's the usual array of highbrows with smug faces letting you know that they wouldn't settle for a lesser sci-fi mag. And next to them is the Hugo award that the magazine won last year at Pittsburgh's WorldCon. That's the third Hugo in a row.

It may well be their last.

I used to love this little yellow magazine. Sure, it's the shortest of the Big Three (including Analog and Galaxy), but in the past, it boasted the highest quality stories. I voted it best magazine for 1959 and 1960.

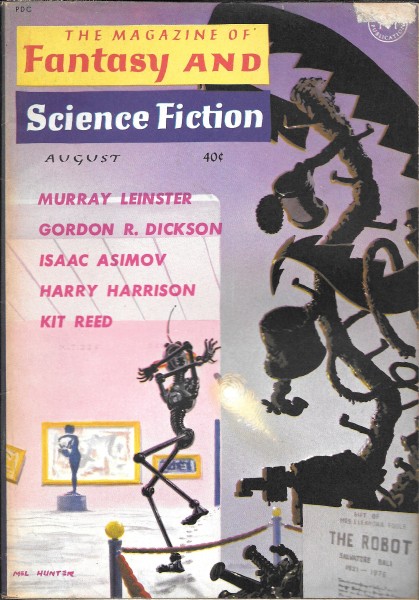

F&SF has seen a steady decline over the past year, however, and the last three issues have been particularly bad. Take a look at what the August 1961 issue offers us:

Avaram Davidson and Morton Klass's The Kappa Nu Nexus, about a milquetoast Freshman who joins a fraternity that hosts a kooky set of time travelers. Davidson's writing, formerly some of the most sublime, has gotten unreadably self-indulgent, and William Tenn's brother (Klass) doesn't make it any better. One star.

Survival Planet, by Harry Harrison, features the remnant colony of the vanquished Great Slavocracy. It's not a bad story, but it's mostly told rather than shown, the book-ends being highly expositional. Three stars.

Vance Aandahl, as one of my readers once observed, desperately wants to be Ray Bradbury. His Cogi Drove His Car Through Hell has the virtue of starring a non-traditional protagonist; that's the only virtue of this mess. One star.

Juliette, translated from the French by Damon Knight (it is originally by Claude-François Cheiniss), is a bright spot. It's a sort of cross between McCaffrey's The Ship Who Sang and Young's Romance in a Twenty-First Century Used Car Lot. I found it effective, written in that Gallic light fashion. Four stars.

For the life of me, I couldn't tell you the point of E. William Blau's first printed story, The Dispatch Executive. Something about a bureaucratic dystopia, or perhaps it's a special kind of hell for office clerks. Hell is right, and here's hoping we don't see Blau in print again. One star.

Then we have another comparatively bright spot: Kit Reed's Piggy. Per the author, it is "the story of Pegasus, although I don't remember that his passengers spouted verse, and a mashup of first lines from Emily Dickinson, whom I admired, but never liked." There's no question that it's beautifully written, but there is not much movement as regards to plot. Three stars.

A Meeting on a Northern Moor, Leah Bodine Drake's poem on the decline of Norse mythology is evocative, though brief. Murray Leinster's The Case of the Homicidal Robots is a turgid mystery-adventure involving the spacenapping of dozens io interstellar vessels. Three and two stars, respectively.

Winona McClintic is back with Four Days in the Corner, some kind of ghost story. It's worse than her last piece, and that's nothing to be proud of. Two stars.

Then we have Asimov's science fact column, The Evens Have It, on the frequency of nuclear isotopes among the elements. The Good Doctor's articles are usually the high point of F&SF for me, but this one is the first I'd ever characterize as "dull." Three stars, but you'll probably give it a two.

Rounding things up is Gordon Dickson's The Haunted Village, about a traveler who vacations in a village whose inhabitants are hostile to outsiders. The twist? There is no outside world – only the delusion that such a thing exists. Dickson is capable of a lot better. Two stars.

I often say that I read bad fiction so you don't have to. This was especially true this month. While Galaxy was quite good (3.4 stars), both Analog and F&SF clocked in at 2.2.

For those of you new to the genre and wondering why they should bother (why I should bother), I promise – it's not all like this. Please don't let it all be like this…

Coming up next: The sci-fi epic, Mysterious Island!