by Gideon Marcus

Ah, and at last we come to the end of the month. That time that used to be much awaited before Avram Davidson took over F&SF, but which is now just an opportunity to finish compiling my statistics for the best magazines and stories for the month. Between F&SF's gentle decline and the inclusion of Amazing and Fantastic in the regular review schedule, you're in for some surprises.

But first, let's peruse the June 1962 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, and see if, despite the new editor's best efforts, we get some winners this month (oh, perhaps I'm being too harsh – Editor is a hard job, and one is limited to the pieces one gets.)

Such Stuff, by John Brunner

Thanks to recent experiments, we now know what people cannot survive long when deprived of the ability to dream. But what about that bedeviled fellow who enjoys an escape from nightmares? And what if your mind becomes the vessel for his repressed fantasies? A promising premise, but this Serling-esque piece takes a bit too much time to get to its point. Three stars.

Daughter of Eve, by Djinn Faine

After an interstellar diaspora, there are but two remaining groups of humans on a colony world. One is a large population of radiation-sterilized people; the other comprises just one man and his young daughter, the mother having died upon planetfall. From the title of the story, you can likely guess the quandary the sole fertile man is faced with. The childlike language of the viewpoint character (the daughter) is a bit tedious, but this first story by Virginia Faine (nee Dickson – yes, that Dickson) isn't bad. It stayed with me, and that's something. Three stars.

The Scarecrow of Tomorrow, by Will Stanton

Reading more like a George C. Edmondson tale than anything else, this pleasantly oblique tale describes the encounter between two farmers and a murder of crows…with a partiality for things Martian. I reread the ending a half-dozen times, but I'm still not quite sure what it all means. Nicely put together, though. Three stars.

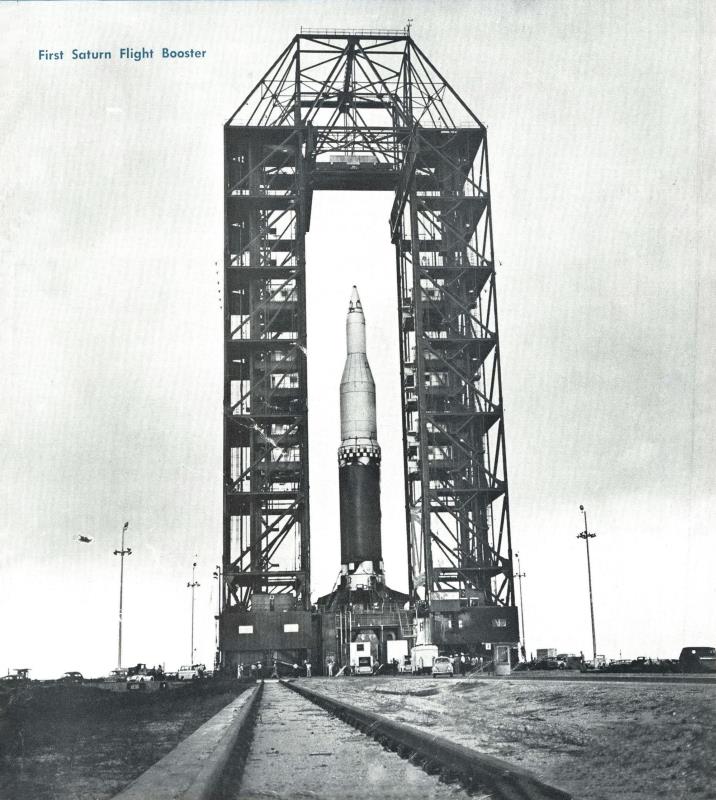

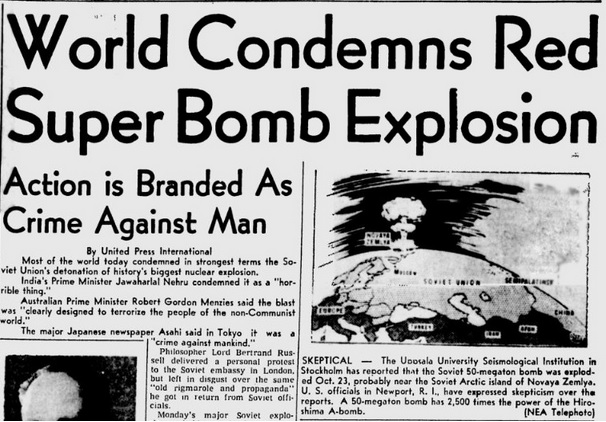

The Xeenemuende Half-Wit, by Josef Nesvadba

During the War, a prominent German rocket scientist is stumped by a thorny guidance problem. Can his savant son help him out? And is it worth the price? Another moody, readable piece from Nesvadba. I'm sure there's a point, but I'm not quite sure what it is. Three stars.

The Transit of Venus, by Miriam Allen deFord

I don't usually go for expositional stories, but deFord makes this one work, particularly with the story's short length. In a world of regimentedly liberal mores, one prude dares to turn society on its ear with a scandalous go at winning the Miss Solar System beauty pageant. A fun piece from a reliable veteran. Three stars.

Power in the Blood, by Kris Neville

I didn't much like this story when it was It's a Good Life on The Twilight Zone, and I like it less here. Some addled old woman with the power to destroy slowly deteriorates the world until there's naught left but wreckage. Disjointed, unpleasant, and just not good. One star.

The Troubled Makers, by Charles Foster

About the reality-challenged psychic who bends reality to his will, and the Watusi Chief who helps him around. You've seen versions of this story a dozen times or more in this magazine over the years, but it's not a bad variation on the theme. An assiduous copy of the mold from a brand new writer. Three stars.

The Egg and Wee, by Isaac Asimov

I normally enjoy the Good Doctor's essays, and this one, comparing the ovae of various creatures and then segueing to a discussion of the smallest of biological creatures, isn't bad. But it misses the sublimity that his work can sometimes achieve. Three stars.

Through Time and Space with Ferdinand Feghoot: LI, by Grendel Briarton

Mr. Bretnor's latest is much worse than normal, perhaps in Garrett territory. But, I've never included these puns in my ratings, so I shan't now. Lucky for F&SF.

The Fifteenth Wind of March, by Frederick Bland

Penultimately, we've got the jewel of the issue. As magical winds scour the Earth with increasing frequency and intensity, one thoroughly ordinary British family attempts to find shelter before it's too late. Both extraordinary and humdrum at once (no mean feat), it's a poignant slice of unnatural life. Four stars.

The Diadem, by Ethan Ayer

Mr. Ayer's first printed story involves two women and the goddess that connects them. It tries hard to be literary, but is just unnecessarily hard to read. Two stars.

It should be clear to one with any facility with math (and who read every article this month) that the June 1962 F&SF was not the prize-winner this month. In fact, the Goldsmith mags took surprising first and second place slots with 3.4 and 3 stars for Fantastic and Amazing, respectively. Galaxy and Analog tied at 2.7 stars. F&SF rated a middlin' 2.8, but it may have had the best story, though some will argue that Fantastic's The Star Fisherman earned that accolade. It also had the laudable achievement of featuring the most woman authors…though two is hardly an Earth-shattering number.

Speaking of women, the next article will feature women in the army. And on that progressive note…ta ta for now!